On Tuesday, October 18, an exhibition, “Shrines of Serbia—Those Destroyed and Those Under Construction”, opened at the “Cathedral Chamber” Historical, Cultural and Educational Center of St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University of the Humanities in Moscow as part of the “Serbian Consolation to the Russian Heart” international festival. It closed October 28.

The authors of the exhibition are Elena Osipova, a Masters in Languages and Literature, Associate Professor of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature of St. Tikhon’s University, Senior Researcher at A.M. Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences; and Maja Acimovic, Librarian at the Department of Orthodox Theology of University of Belgrade.

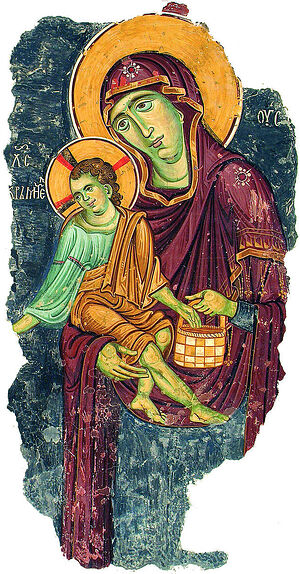

The Most Merciful Mother of God with Christ, the Feeder of Orphans. Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska, 1308–1314 Elena Osipova spoke about what can be seen and understood at this exhibition:

The Most Merciful Mother of God with Christ, the Feeder of Orphans. Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska, 1308–1314 Elena Osipova spoke about what can be seen and understood at this exhibition:

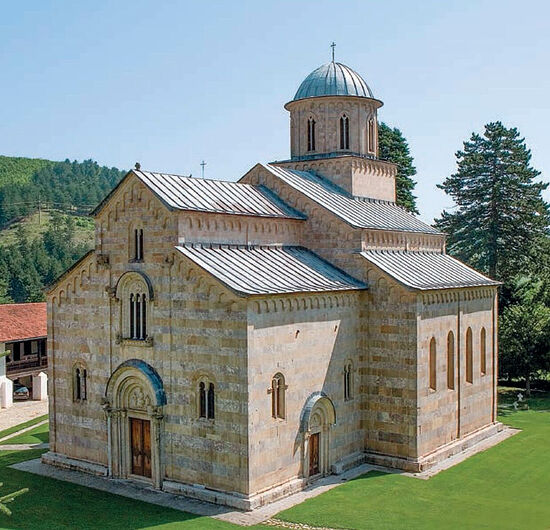

—The idea of our exhibition is to show several aspects related to Serbian holy sites at once. We sought to support the Serbs’ hope that their presence in Kosovo will remain unchanged, despite all the dramatic vicissitudes of fortune in previous centuries and relatively recently. Kosovo and Metohija is a region closely connected with Serbian history and the period of the formation of national statehood. But it is also connected with the history of the entire Christian civilization, since the churches and monasteries of Kosovo and Metohija are an artistic and cultural heritage of world significance and a great spiritual treasure of the Orthodox world. It is no coincidence that many of them are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Visoki Dečani Monastery, Gracanica Monastery, the Patriarchate of Pec’s Monastery, and the Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska. They were created by the best medieval Greek, Serbian and other European builders and artists, and today they remain true masterpieces of world art.

We also wanted to show everyone who visits the exhibition that these churches and monasteries have shared the fate of the Serbian people throughout their history. Many of them were repeatedly destroyed, but then restored again—along with Serbian life in this ancient Serbian land. The Serbs often had to defend their shrines even with weapons hand. This can be seen in the periods of history when Serbia temporarily lost its statehood. For example, during the Ottoman yoke, which lasted longer in Kosovo than anywhere else in the Balkans: from the mid-fifteenth century till 1912. Then there was a short period of freedom, but starting from 1945, when the Communists came to power in Yugoslavia, extremely difficult times began again for the Serbs. These events are reflected in the book by Archpriest Savo Jovic entitled, Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide of Slavic Culture in Kosovo and Metohija: Testimonies of Suffering of the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Serbian People from 1945 to 2005. Basing his information on rare and previously unknown archival sources, the author, testifies to the suffering of the Serbian Church and the Serbian people under the Communists, who condoned the atrocities committed by local Albanian extremists.

The Patriarchate of Pec’s Monastery

The Patriarchate of Pec’s Monastery

At the same time, using historical examples from the life of the Serbian nation and its ancient churches and monasteries, we wanted to show that Kosovo was not broken—not during those hard times and not now—it remains Serbian in spite of everything... Ancient monasteries are active, attracting many, many people from Serbia and other countries. All of them come there to venerate the relics of Serbian ascetics and holy hierarchs and see this unique beauty, an island of real Christian Europe, “the land of holy miracles”, in the fitting expression of the Russian Slavophile and poet Alexei Khomyakov.

—Which monuments can be seen at the exhibition?

—We have tried to show fragments of frescoes of the most famous monuments of Serbian church architecture, which are listed as UNESCO heritage Sites. Photos of the Monastery of the Patriarchate of Peć are displayed on two large stands. This is a unique monastery, and previously it was even called a Lavra. In its spiritual and national significance in the life of the Serbian people, the Patriarchate of Pec’s Monastery is reminiscent of the role played by the famous Chudov Monastery of the Moscow Kremlin in Russian history and public life. Let me also remind you that the Patriarchate of Pec is mentioned in the full title of the Serbian Patriarch: His Holiness Archbishop of Pec, Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci, and Patriarch of Serbia. One of the churches of the monastery in honor of the Holy Apostles was founded in the thirteenth century by Archbishop Arsenije I, a disciple and successor of St. Sava of Serbia. Throughout the centuries the monastery remained the most important center of church and people’s life. Even during the difficult times of the Ottoman yoke, the Serbian people united around the Patriarchate of Pec, which helped them survive physically and spiritually as a historical collective personality.

—The name of the exhibition contains the word “destroyed”. Does it mean that visitors can see photos of damaged churches and monasteries as well?

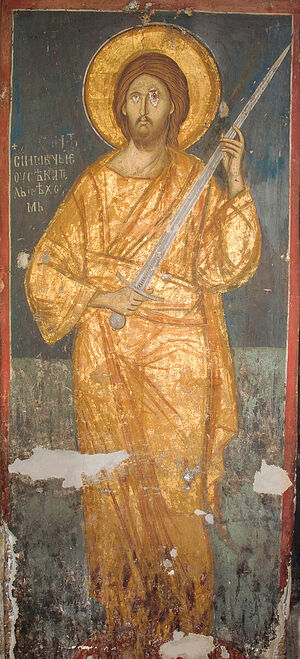

Christ with a sword in His hands. Fresco. Visoki Decani, the fourteenth century —Many of the frescoes of the monasteries we show in the large photographs of our exhibition bear the stamp of the time, including traces of destruction made in various periods, not the least in the late twentieth and the early twenty-first centuries—because the festival covers mainly the events of the last century.

Christ with a sword in His hands. Fresco. Visoki Decani, the fourteenth century —Many of the frescoes of the monasteries we show in the large photographs of our exhibition bear the stamp of the time, including traces of destruction made in various periods, not the least in the late twentieth and the early twenty-first centuries—because the festival covers mainly the events of the last century.

The exposition shows churches and monasteries with very dramatic fates. Some of them were completely destroyed or suffered repeatedly in different times of the twentieth century, but then they were restored through the efforts of the Serbian Church and people. In 1981, even before the 1999 war, one of the buildings of the Patriarchate of Pec’s Monastery was burned down, but then rebuilt. In his work, The Patriarchate of Pec—the Zion of the Serbian Church, our contemporary, a brilliant spiritual writer and preacher, Metropolitan Amfilohije (Radović) of Montenegro and the Littoral, emphasized that this was a deliberate attempt to destroy the most important shrine and spiritual stronghold of the Serbian people. I will add, continuing the parallel with the Chudov Monastery, that we can recall how after the 1917 Revolution the destruction of this monastery in the heart of the Kremlin gave an incentive to the destruction of other Orthodox shrines in Moscow, including the Cathedral of Christ the Savior.

Returning to the exhibition, I’ll repeat that our goal is to show that Serbian Kosovo is not broken: its ancient shrines and people gathering around them are alive despite everything.

I would like to draw your attention to a unique fresco of the Visoki Decani Monastery, which depicts Christ with a sword in His hand. In addition to a deep theological meaning, it reflects a heroic Serbian tradition. Serbian pastors and archpastors of all times up to our days have always called on the Serbs to remember that the Lord gave them this land and that they are obliged to defend it—even with swords in their hands if needed. They acted as spiritual descendants and followers of the holy King Lazar and the Kosovo army who fought “for the Precious Cross and golden freedom.” This thought was reflected in one of the stichera glorifying the feat of Martyr Lazar. It serves as a verbal illustration of the earlier-mentioned fresco of Christ with a sword and praises the king’s military valor: “Loving the Bridegroom’s beautiful goodness and becoming like Christ through struggle and becoming like Him, thou didst cast down the adversary.”

We tried to show at our exhibition that Serbian shrines are not only monuments of church art of the highest artistic value, but also an example of Serbian fortitude and courage. Today, work is being done to preserve and restore them. For example, in 2011, the old Theological Seminary of the holy brothers Cyril and Methodius in the city of Prizren, founded in 1871, resumed its work. In 1999 it had to be closed, and during the unrest in March 2004 the seminary buildings were set on fire and almost destroyed. We should not forget that Serbs remain in Kosovo and continue to live there—so far several dozen thousands of people, but many Serbs believe that time will come when Kosovo will return to Serbia.

—All the monuments, the images of which can be seen at the exhibition, are dear not only to every believer, but also to anyone who cares about human culture...

—Yes, this is the heritage of Christendom, especially the Orthodox world. When our hearts ache for the Serbian people’s suffering, for the destruction of their shrines and the desecration of ancient cemeteries, the spirit of conciliarity and solidarity is awakening in us, strengthening us in various trials. The modern Serbian thinker Vladimir Medenica said wisely about the spiritual significance of this Christian feeling:

“To start with, all of us—both Serbs and Russians—need to at least understand that it’s not some ‘Serbian shrines’ that are burning, but Orthodox churches and monasteries; and that the foundation of not only the Serbian, but also the Russian identity is burning. When the Russian people understand that Orthodox churches and shrines of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church are burning in Kosovo, when they understand that it is not ‘some Serbs’ who are suffering and dying in these expanses, but a people who are brothers in blood and spirit—our own people; when the Greeks, the Romanians, the Bulgarians and all those baptized into one faith understand something of this, this will be the beginning of a new, active love, which Christ entrusted to us.”

—Please tell us about other exhibits.

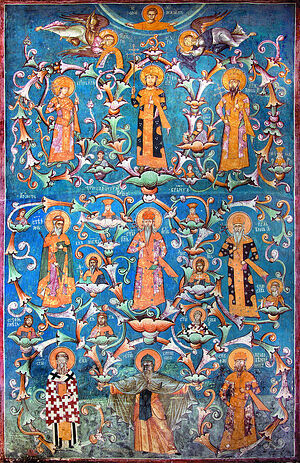

Fresco of holy lineage of Nemanjić Dynasty. Visoki Decani Monastery —At the exhibition visitors could images of frescoes from Gracanica and Visoki Decani Monasteries. In addition to their unsurpassed beauty and artistic value, they are interesting in that their authors tried to comprehend theologically the significance of the Serbian people in history and compare it to sacred history. For example, the Visoki Dečani Monastery has a famous fresco depicting the holy lineage of the Serbian Nemanjić Dynasty (1169–1371) symbolizing the Tree if Jesse.

Fresco of holy lineage of Nemanjić Dynasty. Visoki Decani Monastery —At the exhibition visitors could images of frescoes from Gracanica and Visoki Decani Monasteries. In addition to their unsurpassed beauty and artistic value, they are interesting in that their authors tried to comprehend theologically the significance of the Serbian people in history and compare it to sacred history. For example, the Visoki Dečani Monastery has a famous fresco depicting the holy lineage of the Serbian Nemanjić Dynasty (1169–1371) symbolizing the Tree if Jesse.

Photographs of mosaics and icons of the magnificent Church of St. Sava of Serbia in Belgrade are also part of the exposition. The enormous church was decorated by Russian artists according to the design and under the guidance of Nikolai Alexandrovich Mukhin, a member of the Russian Academy of Arts and a People’s Artist of Russia. Our artists and iconographers’ noble work served to strengthen Russian-Serbian ties that have existed since the twelfth century, and this is very symbolic. After all, it was St. Sava who laid the foundation for these ties; it is known that after a conversation with a Russian monk, the future saint at a young age decided to withdraw from the world and retire to Mt. Athos, where he was tonsured at the Russian monastery. For almost all the subsequent centuries, Russian-Serbian spiritual, cultural and historical ties have remained very close—and, we hope they will remain so in the future.

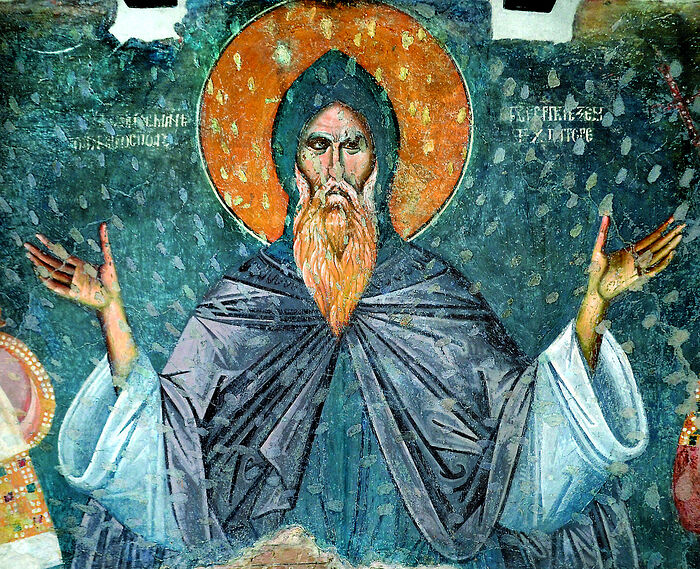

Venerable Simeon the Myrrh-Gusher, founder of Nemanjic Dynasty. Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska, 1308–1314

Venerable Simeon the Myrrh-Gusher, founder of Nemanjic Dynasty. Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska, 1308–1314

—The history of the construction of St. Sava’s Church also corresponds with the exhibition’s name, because it took over 100 years to build it. First, World War I prevented its construction, then World War II, and then the 1999 war... But the church was finally completed and decorated with mosaics, and there have been no more such large-scale artistic church projects in modern Europe.

—Yes, the construction of the church, which began in the late nineteenth century, lasted the whole next century due to interruptions; but thank God, the edifice was finished and decorated with beautiful mosaics at the supposed site of the burning of St. Sava’s relics by Ottomans.

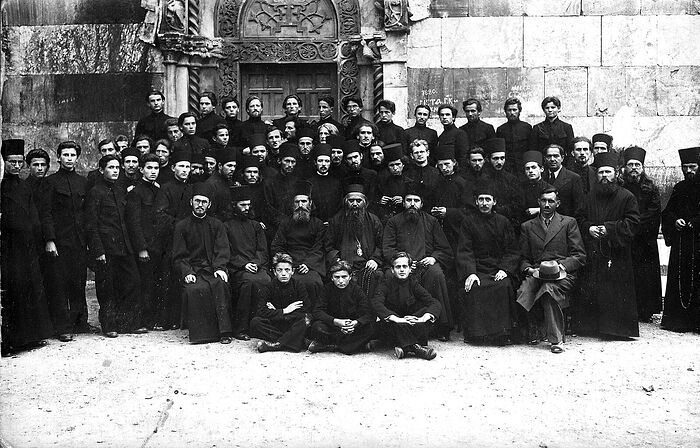

Teachers and students of monastic school of Visoki Dečani Monastery with St. Nicholas of Zica

Teachers and students of monastic school of Visoki Dečani Monastery with St. Nicholas of Zica

—Were there any other images besides frescoes at the exhibition?

—There were also photographs of churches and various episodes from Serbian national life. We couldn’t ignore the Serbs’ suffering in the second half of the twentieth century, including during the 1999 war and the unrest of March 2004 (then more churches were damaged than during the NATO bombing). Thank God, many churches are being restored.

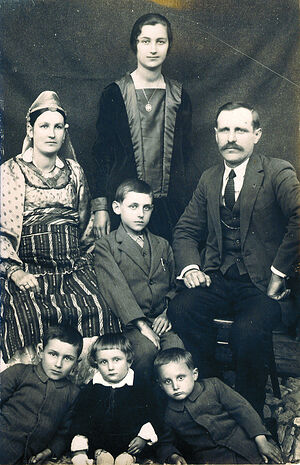

A Serbian family. Kosovo and Metohija. 1930 The Serbian people and their Orthodox shrines have always been very closely linked. St. Nicholas (Velimirovic) used to say that the people of God are the living Church. So we have tried to show some historic photographs of Serbian families of Kosovo and Metohija in the 1920s and ‘30s, along with rare photographs of the Serbian army at the Gracanica Monastery in 1912, or teachers and students of the monastic school of the Visoki Dečani Monastery together with Bishop Nicholas. No one could be left indifferent by rare documentary pictures of a memorial service at the graves of Serbian soldiers who gave their lives for the liberation of Kosovo from the Turks in 1912. Among such photographs is an image of the Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska, once turned into a mosque by Turks. But now this is history, because today it is again an Orthodox church. Unfortunately the magnificent frescoes of this church were badly damaged, but they still shine with amazing beauty today. The fate of the Devic Monastery, which was badly damaged during World War II when an Albanian extremist murdered its abbot, Hieromonk Damaskin, was also difficult. Later, in the late twentieth century, some buildings of the monastery were repeatedly set on fire. But now the monastery has been restored, and in our photographs it can be seen already renovated.

A Serbian family. Kosovo and Metohija. 1930 The Serbian people and their Orthodox shrines have always been very closely linked. St. Nicholas (Velimirovic) used to say that the people of God are the living Church. So we have tried to show some historic photographs of Serbian families of Kosovo and Metohija in the 1920s and ‘30s, along with rare photographs of the Serbian army at the Gracanica Monastery in 1912, or teachers and students of the monastic school of the Visoki Dečani Monastery together with Bishop Nicholas. No one could be left indifferent by rare documentary pictures of a memorial service at the graves of Serbian soldiers who gave their lives for the liberation of Kosovo from the Turks in 1912. Among such photographs is an image of the Church of the Mother of God Ljeviska, once turned into a mosque by Turks. But now this is history, because today it is again an Orthodox church. Unfortunately the magnificent frescoes of this church were badly damaged, but they still shine with amazing beauty today. The fate of the Devic Monastery, which was badly damaged during World War II when an Albanian extremist murdered its abbot, Hieromonk Damaskin, was also difficult. Later, in the late twentieth century, some buildings of the monastery were repeatedly set on fire. But now the monastery has been restored, and in our photographs it can be seen already renovated.

Memorial service at the graves of the Serbs who died for the liberation of Kosovo in 1912. Photo of the early twentieth century

Memorial service at the graves of the Serbs who died for the liberation of Kosovo in 1912. Photo of the early twentieth century

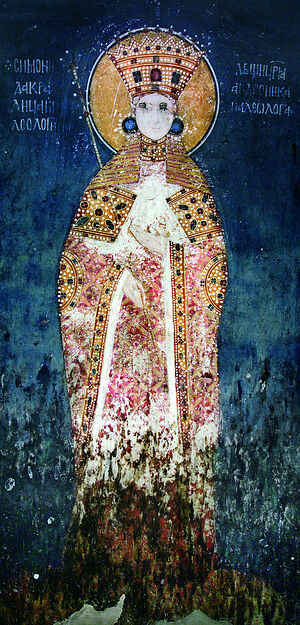

In conclusion, I would like to recall a famous fresco from the Gracanica Monastery. It depicts the Greek Princess Simonida, the wife of the Serbian King Stefan Milutin from the Nemanjić Dynasty. This fresco is called a symbol of desecrated yet unbroken Serbian Kosovo. It was damaged in the nineteenth century when an Albanian sneaked into the church and gouged out the eyes of the princess’ image. The Serbian poet Milan Rakic (1876–1938), inspired by the noble beauty of the Gracanica frescoes, wrote his famous poem, Simonida:

Simonida. Fresco of Gracanica Monastery Your eyes were gouged out, oh beautiful image,

Simonida. Fresco of Gracanica Monastery Your eyes were gouged out, oh beautiful image,

On a pilaster at approach of night,

Knowing that no one would witness the pillage

An Albanian knife robbed you of your sight.

But neither your mouth, nor your noble face

To desecrate with his hand did he dare,

Or touch your golden crown, or queenly lace

Beneath which lay your luxuriant hair.

Now in the church upon the stone pilaster

Serenely bearing your tormented plight

Dressed in the robes of mosaic and luster

I see you sad, and dignified, and white.

Like stars extinguished in the distant past,

Which yet transmit to men the far-off glow

So that men see the light, the hue, the cast

Of stars lost to sight a long time ago,

Today upon me from your royal height,

From that antique stone covered all in grime,

Oh, sad Simonida, shines down the light

Of eyes gouged sightless in another time1.

—So, the main message of the exhibition is optimistic?

—Yes, it is. That is why we’ve chosen the fresco, “The Resurrection of Christ”, from the Gracanica Monastery as the exhibition’s calling card. It, too, suffered greatly at one time—the loss of part of the paint layer passes like lightning through the image. But we remember that the the Resurrection of Christ is the most important event in our faith, and it gives us hope both in this life and in Eternal Life.