This article by Archimandrite Damjan (Cvetkovic) examines the influence of the Russian emigration, in particular Russian monasticism (both male and female), on Serbian monasticism. Owing to Russian priests, theologians, monastics, and ordinary believers who came to Serbia after the revolution, the Serbian Church witnessed a spiritual revival, its groundwork already laid out by the religious movement headed by the Holy Hierarch Nikolai (Velimirović). Among the great number of those who contributed to the revival of the monastic tradition that had literally been abandoned in Serbia under Ottoman rule were Schema-Archimandrite Amvrosy (Kurganov) and Abbess Ekaterina (Efimovskaya), who labored in the monasteries of Miljkov, Kuvezdin and Hopovo.

From Optina to Miljkov

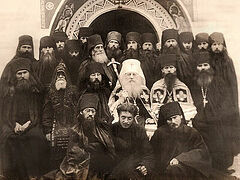

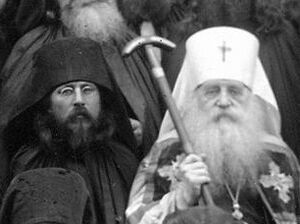

Schema-Archimandrite Amvrosy (Kurganov) and Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) Schema-Archimandrite Amvrosy, in the world Vladimir Zinovievich Kurganov, was born on January 1/14, 1894, in the village of Govorovo, Saransk District, Penza Province, in the family Fr. Zinovy Kurganov, who came from a long line of priests. His grandfather was a priest named Simeon Kurganovi; his mother’s name was Liubov. His mother died early, and the children were brought up by a nanny. It’s known that Vladimir had a brother who committed suicide. Vladimir studied at the Krasnoslobodsk Theological School, and then, until 1912, at the Penza Theological Seminary, though he didn’t finish, instead taking up studies in the Department of History and Philology at Warsaw University.

Schema-Archimandrite Amvrosy (Kurganov) and Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) Schema-Archimandrite Amvrosy, in the world Vladimir Zinovievich Kurganov, was born on January 1/14, 1894, in the village of Govorovo, Saransk District, Penza Province, in the family Fr. Zinovy Kurganov, who came from a long line of priests. His grandfather was a priest named Simeon Kurganovi; his mother’s name was Liubov. His mother died early, and the children were brought up by a nanny. It’s known that Vladimir had a brother who committed suicide. Vladimir studied at the Krasnoslobodsk Theological School, and then, until 1912, at the Penza Theological Seminary, though he didn’t finish, instead taking up studies in the Department of History and Philology at Warsaw University.

While studying at the university, he met his first father confessor Archpriest Konstantin Koronin, who, although he led Vladimir’s spiritual life for a such time, taught him the Jesus Prayer. Some time later, Fr. Konstantin entrusted his spiritual child to Bishop Benjamin, who was in Tver at the time. Communication with his new confessor didn’t last long: When the First World War broke out, Vladimir went to work in a medical detachment where, according to witness accounts, he selflessly labored, caring for the sick and wounded. In 1914-1917, when the Warsaw University was evacuated to Rostov-on-Don, students, including Vladimir, were recalled by imperial order to finish their studies. During this period, Vladimir not only studied the sciences, but he also learned Orthodox praxis under the spiritual guidance of the local parish priest Fr. John, a deeply religious and compassionate man.

Vladimir graduated from the university on the eve of the February Revolution. In Rostov, as a monarchist and patriot, he took an active part in demonstrations for a victorious end to the war. Around the same time, he also traveled back home to learn from simple monks how to love your neighbor and live like a Christian in the challenging circumstances of the early twentieth century. Vladimir lived for a short time at St. Gregory Bizyukovo Monastery in the Kherson Diocese in the south of the country. But not finding what he was looking for there, he went to Moscow to get a military education.

Having graduated from Moscow’s Alexandrovskoe Military School, he became a sergeant major. In October 1917, he participated in the defense of the Kremlin, where he met Archimandrite Benjamin, who introduced him to his spiritual father, Theophan of Poltava. After the defeat of the White Army forces, Vladimir Kurganov managed to leave Moscow for the Optina Hermitage. Since he was in a military uniform and had no papers, he was barely allowed into the monastery to stay for one night. The next morning, he was accepted as a novice and was soon sent to the Optina Skete, where he was given an obedience with the demanding gardener monk Fr. Job. It was said that whoever could work with him would become a monk. The spiritual development of novice Vladimir was led by Elder Nektary and the head of the skete, Fr. Theodosius. Following the revolution, he remained a novice at the Optina Hermitage, and Igumen Theodosius of Optina became his spiritual father.

The future Schema-Archimandrite Amvrosy fought on the side of the White Army in the civil war and was seriously wounded

He fought on the side of the White Army in the civil war and was seriously wounded. Later on, he emigrated to Constantinople, after which he went to Serbia to Miljkov Monastery. He left an indelible mark on the ecclesiastical and social life of this monastery.

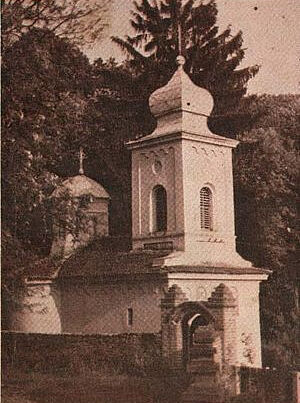

Miljkov Monastery received its present name in the second half of the eighteenth century. It was formerly known as Bukovica. We don’t know for certain who founded it. Some believe it was the despot Stefan Lazarevic (however, this is nothing more than an assumption). The earliest written document that mentions Bukovica Monastery is the “Chrisovula” (or charter) of Prince Lazar from 1347, which states that the prince granted dependencies to Ravašnica Monastery. Among others, it mentions “the Bukovica ford at Gložan on the Morava River.” It’s known that around 1420, Bukovica monastery had a school of scribes. Since there’s no information about the monastery in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (during Ottoman rule), it’s safe to assume that it was destroyed and burnt to the ground.

In 1787, the monastery was restored at the expense of Milko Tomić, a merchant from the village of Gložan, and renamed Miljkov after him. Milko lived in the monastery in his later years and was buried there. Apparently, the monastery was destroyed and burned down during another Turkish occupation. The restoration of the monastery began around 1820.

Miljkov Monastery In the twentieth century, Miljkov Monastery became a place of Russian-Serbian monastic symbiosis. In 1914-1915, the brotherhood of the monastery consisted of only two people—a hieromonk and a hierodeacon. The rebirth of the monastic community of Miljkov Monastery is associated with the name of Archimandrite Amvrosy Kurganov (†1933), who labored there since 1926.

Miljkov Monastery In the twentieth century, Miljkov Monastery became a place of Russian-Serbian monastic symbiosis. In 1914-1915, the brotherhood of the monastery consisted of only two people—a hieromonk and a hierodeacon. The rebirth of the monastic community of Miljkov Monastery is associated with the name of Archimandrite Amvrosy Kurganov (†1933), who labored there since 1926.

Elder Amvrosy gathered a large brotherhood made up of both the Russian refugees and Serbs. According to his biographer, he was most happy about the growth of mutual love in the monastic brotherhood. This is especially evident in the description of life in the monastery and the monastery typicon. The Divine Liturgy was celebrated daily in the monastery and the daily liturgical cycle was strictly observed. The brethren sang on two kliroses, alternating Byzantine and Serian chants. Sometimes Elder Amvrosy himself directed a choir or serve as canonarch. He often celebrated the Divine services and gave homilies (usually about non-condemnation and love). He was very concerned about the active liturgical life of the brethren. He often exhorted them to partake of the Holy Gifts. In those cases when someone explained his refusal to commune often by his unworthiness, he would teach them to approach the chalice saying: “Oh, Lord, how unworthy I am.” Beyond the services, the iconographers among the monks who came from Valaam Monastery taught the Serbian monks iconography, while Elder Amvrosy translated the works of the Holy Fathers. In the refectory, they always read from the lives of the saints and The Philokalia. The Elder maintained fraternal relations with Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky), Bishop Theophan of Poltava, and Hieromonk John (Maximovich), the future St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco.

Firmly established in the hesychast tradition of the Holy Mountain (that was passed down from St. Paisius Velichkovsky and his disciples in the late eighteenth century and restored at the Optina Hermitage), Elder Amvrosy was a zealous man of prayer. One of those who personally knew Elder Amvrosy wrote:

He didn’t write any books, he didn’t make any speeches, he rarely preached, but he won our hearts with his love more than all the speeches and books we’ve ever listened to or read.

Miljkov Monastery St. Thaddeus of Vitovnica also testified to this, emphasizing that Elder Amvrosy had the gift of the unceasing Jesus Prayer. As a novice at Miljkov Monastery, he had a chance to meet Elder Amvrosy in person and left the following recollection of him:

Miljkov Monastery St. Thaddeus of Vitovnica also testified to this, emphasizing that Elder Amvrosy had the gift of the unceasing Jesus Prayer. As a novice at Miljkov Monastery, he had a chance to meet Elder Amvrosy in person and left the following recollection of him:

I saw that the Elder Archimandrite Amvrosy correctly understood that the Lord wants us to become love. Love reigned in him.

The beneficial influence that Elder Amvrosy, the conduit of the Optina tradition, had on Elder Thaddeus is evident both from his direct testimonies and the spiritual counsels of the Elder he recorded.

The monk and future theologian Cyprian (Kern), who lived at Miljkov monastery from Pascha 1926 to Holy Week 1927, and wrote in his memoirs about life in the monastery: “In terms of pure asceticism, everything was good and salvific.” Cyprian (Kern’s) testimony is particularly valuable since he was wary of monastic life: He agonized over the “horrors of monastic life,” “the unsophisticated physical labor,” “the environment full of illiterate people,” whose sphere of interest was about “their daily bread, the news of the monastery, and who is to serve tomorrow.”

From Lesna to Hopovo and Kuveždin

Abbess Ekaterina (Efimovskaya) The tradition of female monasticism in Serbia was interrupted during Ottoman rule, and until the end of First World War, there was no prospect of restoring it. It began to revive thanks to the God Worshipper Movement led by St. Nikolai (Velimirović) and the sisters of the famous Lesna Convent. Approximately eighty nuns headed by Abbess Ekaterina (born Evgenia Borisovna, Countess Efimovskaya; 1850-1925) joined the Serbian Orthodox Church. Ending up in the major monasteries of Fruška Gora, Hopovo, Kuveždin, and Petkovica, the Lesna sisters contributed to the fact the Serbian women began to adopt monasticism.

Abbess Ekaterina (Efimovskaya) The tradition of female monasticism in Serbia was interrupted during Ottoman rule, and until the end of First World War, there was no prospect of restoring it. It began to revive thanks to the God Worshipper Movement led by St. Nikolai (Velimirović) and the sisters of the famous Lesna Convent. Approximately eighty nuns headed by Abbess Ekaterina (born Evgenia Borisovna, Countess Efimovskaya; 1850-1925) joined the Serbian Orthodox Church. Ending up in the major monasteries of Fruška Gora, Hopovo, Kuveždin, and Petkovica, the Lesna sisters contributed to the fact the Serbian women began to adopt monasticism.

The statistics released by Radoslav Grujčić indicate that the impetus for the revival of female monasticism in Serbia was the arrival of Russian nuns from Lesna: After 1921, the Serbian Orthodox Church had 3,179 priests, 346 monks, and eighty-three nuns. According to the census in accordance with the “Schematism” of 1925,

prior to the unification of the people and the Church, convents almost completely disappeared in our country and we had only seventy-five Orthodox nuns in our country.

According to historical research, anywhere from seventy-five to eighty nuns arrived through Bessarabia to a new South Slavic state along with the abbess from Lesna (Kholm Province). The sisters who came to Kuveždin were sent to the neighboring monastery of Hopovo, which had a better logistical capacity to accept and house the newly arrived nuns, since it had a home for abandoned children on its premises.

From the report of the Holy Synod to the Minister of Religion we learn that the number of Lesna nuns was unexpectedly big for Serbia:

As you already know, sixty to seventy Russian nuns from the Lesna Convent have recently moved to our country.

Contemporaries noted the importance of the Russian example for the revival of female monasticism in Serbia

Contemporaries noted the importance of the Russian example for the revival of female monasticism in Serbia. Kuveždin Monastery, located not far from Hopovo monastery, turned into a real monastic alliance of Russian and Serbian women.

We get some information about the economy and the number of the nuns from the first monograph about the monastery (twenty-four nuns and 575 acres of land and forest). Russian Metropolitan Evlogy (Georgievsky) wrote:

The arrival of the Lesna Convent was of great importance for Serbia. The fact is that female monasticism died a long time ago in Serbia. Over the last few centuries, there hasn’t been a single convent in Serbia and the Serbs began to consider this to be perfectly normal.

Thus, Serbian female monasticism has Russian roots:

Christ, Who brought the Russian nuns here, wanted them to light the candle of their Serbian sisters and kindle the fire of love for Christ.

The monastery, established through the joint efforts of the Russian and Serbian nuns, became a true spiritual center, and the philanthropy and charity of the nuns became the monastery’s “calling card” when it was still an orphanage.

The Bishops’ Council petitioned Patriarch Dimitrije to allow the establishment of “a convent in Kuveždin Monastery that would take over the care of the orphanage.”

In 1929, the nuns of Kuveždin Monastery began to provide care for residents of a home for the elderly and infirm in Sremska Mitrovica. Five nuns labored at this obedience. In the same year, they took over care of the orphanage, kindergarten, and canteen for the poor of the church community in Sarajevo. Thus, Kuveždin became a new phenomenon in the Serbian Orthodox Church in the spiritual, moral, and social and all other senses of the word.

The example of the nuns of Kuveždin Monastery attracted the attention of public figures and intellectuals, who spoke of the need to pay more attention to Kuveždin and the Russian Hopovo Monastery, which became examples of good social practices and a model for other monastic communities.

Among the proponents of the revival of female monasticism was Marija (Ilić-Agapova), the first educated Serbian woman

Among the proponents of the revival of the spiritual life and female monasticism in Serbia, I would like to mention the first educated Serbian woman, the librarian Marija (Ilić-Agapova). She spoke on a Belgrade radio station about the goals of women’s monastic ministry and the modern situation with female monasticism in Serbia. Her talk helped popularize female monasticism, and women’s communities began to form in other Serbian monasteries after the example of Kuveždin and Hopovo Monasteries. For example, in the vicinity of Niš, by decision of the Holy Synod, the Monastery of St. Jovan became a convent. At the initiative of the People’s Union of Women, a co-op for blind girls was formed there whose members learned tailoring at the home for the blind in Zemun.

There was another monastery in southern Serbian—the Monastery of St. Kirik near Caribrod—where Russian Lesna nuns also lived. In the middle of 1932, Divljana monastery had forty nuns and novices engaged in various obediences, including iconography. With the increase in the number of sisters, the monastery expanded its economic and housing facilities.

The revival of female monasticism in the Serbian Orthodox Church gave impetus to the development of Christian culture and piety in local women. Even if all kinds of women's philanthropic and religious societies existed there before, the focus of their activities now shifted towards Christianity. Pious women published various ideas in the religious press.

In March 1920, the Women’s Christian Movement Society was founded. It aimed to strengthen the faith and morals of the people. The members of the society saw the means of achieving their goals in personal exploits and the organization of educational activities: lectures, publishing, and establishing “closer contact with the world of women and children.” The Women’s Christian Movement, which carried out its social activities based on Christian ethics, worked under the patronage of Queen Mary and the supervision of the Holy Synod and the Serbian Patriarch.

In keeping with the trend of the development of women’s piety in general, and monasticism in particular, a new convent in the name of St. Paraskeva-Petka was founded in the Metropolia of Zagreb. Metropolitan Dositej (Vasić) got the idea of founding such a monastery as early as 1933 when he arrived in Zagreb. Just three years later, on March 16/29, 1936, he took part in the consecration of the monastery. The nuns did a lot of social work and carried out obediences helping single mothers, poor children, and generally anyone in need, with the active support of Metropolitan Dositej. Charitable work was a priority among the monastery’s activities. At the beginning of 1938, there were twelve nuns in the monastery with Mother Taisia as its abbess. The sisters also did needlework, and many of them studied the basics of medicine in order to become nurses and do social work, which was the main activity of the sisters of the Roman Catholic church.

Archimandrite Damjan (Cvetkovic)

Archimandrite Damjan (Cvetkovic)

Unpublished data from the “Schematic of the Serbian Orthodox Church” from 1940 provides some information about the monastery and its nuns. In particular, it’s known that Abbess Taisia (Procopiuk) was among the Russian refugees. Three nuns from the sisterhood of the St. Paraskeva-Petka monastery in Zagreb worked in the orphanage of King Alexander I the Unifier in Zagreb. The name of Metropolitan Dositej (Vasić) of Zagreb is recorded in Church history as the founder of the St. Paraskeva Convent: “He labored to prepare Orthodox nuns to work in hospitals.”

After the First World War, despite the colossal losses, the Serbian Orthodox Church witnessed the revitalization of its spiritual life

Therefore, after the First World War, despite the colossal human and economic losses, the Serbian Orthodox Church witnessed the revitalization of its spiritual life, while the Russian refugees, as it turned out, were sent by Divine providence to carry out an important mission—to help their sister Church and the fraternal people who welcomed them during the years of persecution and trouble.

As St. Gregory of Nyssa said, there are thousands of roads of death, but there are many more paths of love. Those Serbs and Russians who helped each other walked these paths of love.