In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!

Dear brothers and sisters, I would like to greet you all on the first week of Lent. There were weeks that prepared us both physically and spiritually, but still, the first week is a certain impetus that can give us strength to continue fasting. The circumstances of the time encourage and force us to be more self-disciplined and serious and to understand that our prayer matters. If I fast more strictly, limiting myself in something, it will be not just for myself, but in order to make a contribution that is bearable for me.

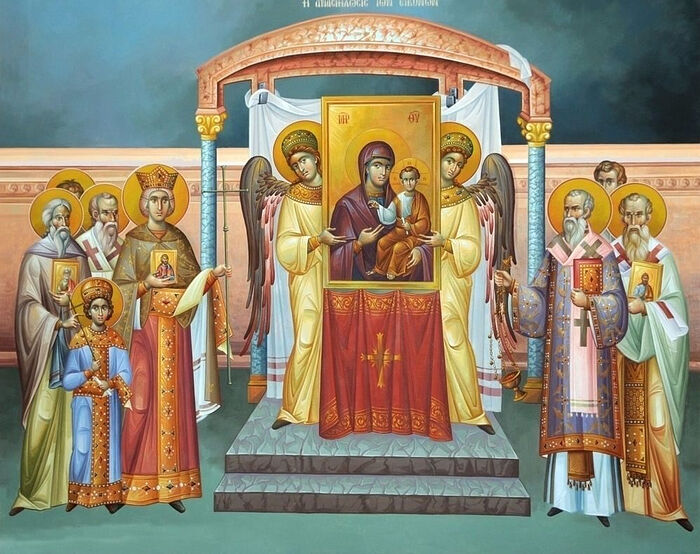

This week ends with the Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy. On the one hand, it seems that initially this event had nothing to do with Great Lent, but, on the other hand, this is because the restoration of the veneration of icons took place on this day in 843 and fell on the first Week of Great Lent.

It is a very unusual period in the history of the Church that lasted over 100 years. Over its history the Church has rarely been in a quiet state: something has always tormented it, something has always bothered it. Sometimes it was from the State, and sometimes there were internal schisms. And at that period in the history of the Church, great contradictions converged: political, religious, military and social. And indeed, the Church of Christ was being torn apart by the heresy of iconoclasm; it ebbed and flowed, making people suffer. It always happens in the Church to affirm Orthodoxy, and the Church always overcomes these circumstances. That time was no exception. Theological thought was perfected and rose to a new level after a period of stagnation. New saints and confessors appeared again. Take Sts. John of Damascus, Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople, Theodore the Studite... We still use their writings. What was the Church looking for? What was Orthodoxy seeking? What were people striving for and moving towards during all these heresies that disturbed and tormented the Church? Always towards the same thing—to prove, to show that God is available to man, that God acts in this world, and that the saying is unfair that goes: “God is high, and the king is far away” (meaning that we are left to ourselves). God is with us, and we can unite with Him. Of course, people who got to know this by experience did not have any doubts, but the right to depict Christ the Savior on icons was in fact the end of the Christological arguments of the first centuries of Christianity. It is the understanding of the Incarnation, the understanding that God truly became Man, while retaining His Divinity. And since He was incarnate, since we saw Him, since He is a Person, we can depict Him; and by this the Church not only defended its tradition, but also its right to be with God, the right to commune with God.

What does this mean for you and me? Why are there icons in the life of every believer? We understand that we need help on our path of the knowledge of God. We are weak, we are fickle, we definitely need some kind of “supports”, “props”, and in fact everything that is in the Church, including icons, is the hand of God helping people. Of course, you can pray without icons: the experience of the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church of the twentieth century shows that, of course, they prayed as they languished in labor camps for many years without icons.

We know real ascetics who went into seclusion for communion with God, who contemplated God through their ascetic labors—they all had icons in their cells. Having such a high level of communion with God, the ascetics still needed icons. If a small icon was somehow handed over to an imprisoned bishop, priest or layman in the camp, he would rejoice.

The word “icon” in Ancient Greek means “image”. We know that the first icon in the world was Adam, created in the image and likeness of God. The image and the likeness are in reason, in creativity, in freedom. And the Church calls on us to treat all people around us as icons, as reflections of the Divine image. Sometimes it is hard to see an icon, an image of God in a person. People even say: “This person has completely lost the image of God,” that is, he has so darkened it in himself.

One of the most venerated icons is the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God, which is linked to our monastery. I think that most of you have visited the church at the Tretyakov Gallery and seen this icon. Although it lost a layer of paint and does not appear before us in its original form, and its value has never been lost. There are icons in some monasteries and churches, which were shot at during the persecution of the Church in the twentieth century.

What do icons mean in our lives? Why are they in our homes? As amulets? Or can they help us make the right decision in some cases? We we’ve grown so accustomed to icons that we can allow ourselves to swear, use foul language while passing by icons, or be rude with someone on the phone in their presence. And then it turns out that icons as relics have no effect on us; and this is a very important point.

What are icons in my car for? As an insurance against financial losses? Or as reminders that I will now be polite on the road, that I will not get annoyed if, relatively speaking, someone there breaks the rules and creates a dangerous situation? What are icons for?

Icons can help us simply by their presence, being close to us. Now there are many icons and they are available. As a child I saw a black-and-white icon painted with colored pencils at my grandmother’s house. Then, the Soviet era, there were simply no icons, and people used to pray in front of such almost homemade icons. I also happened to visit the house of a priest, a real ascetic, who lived a very difficult life, and after his death it turned out that he had been a secret monk who had endured a lot of trials in his life. When people entered his house, they were amazed by how many icons—even very simple and tiny ones—had found their place in his home. We know that there were many icons in the cell of Archimandrite John (Krestyankin).

One of the twentieth century ascetics of Holy Mount Athos used to say: “Do not forget to light icon-lamps in front of icons of the Mother of God.” This is what we call piety. The word “piety” is repeated several times in today’s service and resounds in the service of the Triumph of Orthodoxy.

Beyond all doubt, iconoclasm still continues; it was not over in the ninth century. We know of medieval frescoes with scratched faces, we know of bonfires of icons in the first half of the twentieth century in our country, and we know of broken and destroyed frescoes. Brothers and sisters, we must appreciate the image of God, appreciate the icon and make it our true help on our difficult path to God. Amen.