Everyone called her “Pinochet”—both children and adults.

Augusta Mikhailovna was the namesake of the infamous Chilean dictator Augusto and his female incarnation, according to most people who knew her. Actually, she was the head of studies of a once prestigious, and now ordinary and reputationally bankrupt Spanish language school.

She kept her subordinates in fear, always speaking straight from the shoulder in a fit of temper. As for money, she did not hesitate to take bribes in envelopes.

Her husband and daughter were quiet, like trained animals. Both at work and at home, “Pinochet” reigned in an absolute monarchy. The 1990s came, and with them the arrogant, boorish, young, and progressive.

Augusta Mikhailovna was caught while taking a bribe and kicked out of her beloved school like withered gladiola given to a teacher on September 1, and sent into retirement. She was also said that she must thank the school administration for not initiating a criminal case against her. Wonderful times ended.

A new stage of life began. Her daughter got married and became pregnant. In retirement “Pinochet” hated the whole world. These were troubled and hungry times, especially for them, as they were used to having everything they needed and more. Her granddaughter Galina was born. This name is of a Greek origin and means “silence”. But her granddaughter screamed nonstop, like her grandmother when she worked at school.

Augusta Mikhailovna would put earplugs into her ears at night, but she could still hear the hysterical “Aaaaaa!” even through the earplugs.

Once, little Galina had a bad fever and they couldn’t get her temperature down. By the morning she had stopped screaming. Luckily, the ambulance arrived in time. It turned out that the baby had meningitis.

The girl survived, but stopped developing completely. She would lie in the stroller and look senselessly ahead of her, at the sky. Maybe she saw clouds, maybe not. Once, while walking, “Pinochet” met her former student, a hooligan with the surname Samsonov, whom Augusta had kicked out after the ninth grade, her decision motivated by the fact that the school did not need imbeciles.

Samsonov was dressed smartly. Seeing “Pinochet”, he grinned slightly:

“Your granddaughter looks like you, Augusto Mikhalna! Your faces are identical!”

Little Galina was salivating, with her head tilting to the side—at the age of three she could bare hold it up ...

“Are you serious? Like me? Thank you, Samsonov! It means I'm very beautiful!” Augusta answered with a challenge and, straightening her back, walked past.

Once as Augusta Mikhailovna was walking with her granddaughter she saw a beautiful church. “Pinochet” had never crossed the threshold of a “spiritual institution” before. Without knowing why, stumbling over the steps of the high church porch and puffing, she dragged the stroller up...

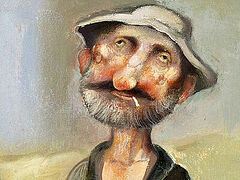

An old gray-haired priest with a Book of Needs came out to meet her. He was waiting for a family for Baptism at that moment.

“Are you going to be baptized? Well done for not being afraid of the weather!”

Fr. George, whom Augusta Mikhailovna had “accidentally” met at the right time, not only later baptized Galina and her grandmother, but also blessed her daughter to have another child.

At first “Pinochet” was opposed to it, wondering how they would raise and feed the children.

But the habit of vertical relationships took over. The priest stood OVER Augusta, and she immediately understood and accepted it, if not with her heart, then with her mind.

She obeyed the priest as if it were an order of the RONO (the District Department for People’s Education). And orders are not negotiable.

She would come to confession weekly with a notebook filled with sins. Her sins, divided into groups, were written in different pens.

“I didn’t believe in the mercy of God”, for example, was always written in red.

Meanwhile, Galina gained two younger sisters. Her daughter’s husband did not go to church, and the two of them would “collect” their scattered children at Sunday Liturgies.

Sometimes she met her former students there, and with amazement they recognized the former school dictator in the modest, bent old woman.

“She has run to church from grief to atone for her sins. Her eldest granddaughter is handicapped...” Such whispers were sometimes heard.

However, “Pinochet” was quite happy. At services she stood with a thick journal and read something carefully from there. Galina was already twelve; she had learned to hold her head and herself upright by that time.

It was so little. But for her grandmother it was very much—the fruit of Herculean efforts.

The younger mischievous sisters would run around her, but never offended her. They would Hug and caress her and then would run to play. These were good, healthy girls.

Their life was hard. Although her son-in-law, a plumber who earned as much as a school watchman during her “reign”, “Pinochet” did not condemn him. Even when she cooked “beggarly” processed cheese soup for the family. She did not condemn him because Fr. George forbade her to judge anyone.

There was no ray of hope. Her son-in-law repaired toilets, and his income was just enough for the most necessary things—to buy clothes and shoes and to go to their dacha in the summer. Is that life? Augusta made good reserves of pickles and jams, and this was a great help.

On the winter feast of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Augusta Mikhailovna’s alarmed daughter called her into the kitchen and said that she was pregnant again... At first “Pinochet” shouted, frightening Galina, and then ran to Fr. George for a blessing so everything would be as it should be.

“Bless my daughter for an abortion, batiushka. There is no other way out. We are already making great efforts to provide for three children,” she said in a businesslike manner.

After listening to her, the old priest burst into tears.

“All these years in the Church have been wasted, Augusta... You’re a barren fig tree...”

So there was no abortion. Her daughter flatly refused an abortion and spent her entire difficult pregnancy in the hospital for the preservation of her baby. There was a threat to both her life and the baby’s. Augusta took care of the children and ran to church when she could without any notebooks or words—she would simply fall to her knees and pray with tears.

She only implored God:

”Take me, but don't take them!”

A healthy boy was born almost at term. Her son-in-law, a plumber, was happy and proud—not only was a son born, but he also found a good and well-paid job in the company of his childhood friend. And the city quite unexpectedly gave them an apartment. Life seemed to be improving, but Augusta had lost half her weight. They thought it was from worries and stress, but it turned out to be cancer. She endured it and did not complain, but when she underwent an examination, the doctor said only, “It’s too late.”

The parishioners at the church did not know that she was dying. Her eyes shone, she smiled, rejoiced at her grandson, and, of course, was always with Galina. Her strength rapidly failed her.

Fr. George gave her Communion for the last time at home three days before her death. Augusta took to her bed and never rose again. The old priest understood and saw everything. Augusta lay peaceful, bright, and not of this world.

“Batiushka, you know, I’ve just now come to believe in the mercy of God. Only now. Strange enough: When I lived I did not believe in it, but now that I’m dying I believe,” the one who had once been known as “Pinochet” said.

God works in mysterious ways. For this thy brother was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found (Lk. 15:32).