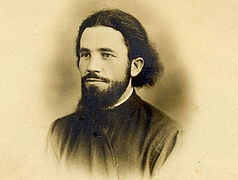

Archimandrite Justin (Pârvu) (February 10, 1919–June 16, 2013) is one of the most famous Romanian elders of our time. In 1948, he was arrested and sentenced to twelve years in prison “for his political views.” In 1960, at the end of his sentence, he was given another four years in prison for refusing to renounce his Orthodox faith.

—You spent sixteen of your eighty-eight years in prison.

—Yes, but those were the most wonderful years, because if not for them, I wouldn’t be what I am now. Know that man doesn’t know how to arrange his life in freedom. He’s very unstable and influenced by everything around him. And if he’s forced against his will to form his character, to follow a certain position and line of behavior, then begins the suffering that sanctifies him.

Orthodox Christianity wouldn’t be Orthodox Christianity if it hadn’t gone through 200 years of persecution. If it hadn’t passed through the whole Middle Ages, and right up to our day. Because Christianity has always had to bleed, if not here, then there. Christianity is still bleeding—and continues to live from generation to generation. After all, the blood of the martyrs is the seed of Christianity. And the life I led during those years was perhaps the most fertile and beautiful, because all those sixteen years I was moving from death to life and from life to death. And I experienced my entire evolution, which is extremely beneficial for a man being formed for life.

—And you experienced the most beautiful Pascha…

—The most beautiful Pascha!

—... at the Baia Sprie Mine.1

—I served Liturgy there, maybe so I wouldn’t do it later. Maybe that’s why God punished me today, and just before Pascha I fell and broke my kneecap. Maybe, I did something wrong… But it was beautiful, because the Liturgy celebrated there, under the watchful eye of the militiaman standing outside the door isn’t an easy thing. If he caught you praying like that, he’d give you hell!

Entrance to the Baia Sprie Mine Fr. Calciu spoke about how he served the Liturgy in his cell. There was no bread, only some wine and utensils, and the most terrible policeman on guard in the ward! You couldn’t even talk to him. On holidays, such people were intentionally put on guard on holidays to do prison training. And then Fr. Calciu knocks on the door. And this man comes up and opens it:

Entrance to the Baia Sprie Mine Fr. Calciu spoke about how he served the Liturgy in his cell. There was no bread, only some wine and utensils, and the most terrible policeman on guard in the ward! You couldn’t even talk to him. On holidays, such people were intentionally put on guard on holidays to do prison training. And then Fr. Calciu knocks on the door. And this man comes up and opens it:

“What do you want, bandit?”

“Sir, I don’t have a piece of bread.”

“Bread?! What, is it time to eat?”

He slams the door and leaves. But less than ten minutes later, he returns with a piece of bread.

“Come on, take the bread! Just don’t tell anyone!”

“How could I tell anyone, sir? But you’re now the initiator of our Liturgy here.”

And he celebrated his Divine Liturgy there—an unprecedented thing. With all the gathered altar servers, with all the priests, the Liturgy was celebrated on the body of a sick prisoner who held on after Communion for another six hours and then departed to the Lord. They were lively Liturgies, on the bodies of martyrs. As you well know, when a church is consecrated, they put the relics of martyrs under the holy altar.

Baia Sprie Mine Not even to mention how beautiful the “chiming of the bells” was in Baia Sprie, that is, the various drill bits that we used to drill stone blocks that we hung on a wire and would hit when about 250 people gathered together and sang, “Christ is Risen!” And when we would leave there with these chants, then everyone up above would know that the prisoners were working in the mine. About five unarmed prison guards came in—they didn’t usually approach the prisoners with weapons—and outside, my dears, the battalions of police and security were waiting for us. And with these shouts and Paschal hymns, we came out of the mine, from a depth of 1,300 feet, and our voices resounded all throughout Baia Sprie and Baia Mare. We went straight from the mine to the camp, to the barracks, our shelter. We didn’t even take a bath—we went straight to the bedrooms, and we stayed there for two days. And after two days, they gathered everyone in the yard:

Baia Sprie Mine Not even to mention how beautiful the “chiming of the bells” was in Baia Sprie, that is, the various drill bits that we used to drill stone blocks that we hung on a wire and would hit when about 250 people gathered together and sang, “Christ is Risen!” And when we would leave there with these chants, then everyone up above would know that the prisoners were working in the mine. About five unarmed prison guards came in—they didn’t usually approach the prisoners with weapons—and outside, my dears, the battalions of police and security were waiting for us. And with these shouts and Paschal hymns, we came out of the mine, from a depth of 1,300 feet, and our voices resounded all throughout Baia Sprie and Baia Mare. We went straight from the mine to the camp, to the barracks, our shelter. We didn’t even take a bath—we went straight to the bedrooms, and we stayed there for two days. And after two days, they gathered everyone in the yard:

“Do you know, bandits, why we held you like this, without food? Because you still have this nonsense in your head. Now go, wash up, eat, and get to the mine!”

On Holy Friday they gave us cabbage soup—worse than you can imagine! Salty and sour, so we went to the mine having eaten 3.5 ounces of bread, and worked hungry for a whole day. And on the day of Pascha itself they had a rich, plentiful table—a whole mountain of meat, and they all stayed there at the table, while we went fasting and praying to fulfill our duty and get them the required amount of lead and galena.

Exhibit from the Museum of Mineralogy, Baia Mare. Photo: P. Zhokhovsky, P. Timko

Exhibit from the Museum of Mineralogy, Baia Mare. Photo: P. Zhokhovsky, P. Timko

Exhibit from the Museum of Mineralogy, Baia Mare. Photo: P. Zhokhovsky, P. Timko

Exhibit from the Museum of Mineralogy, Baia Mare. Photo: P. Zhokhovsky, P. Timko

Exhibit from the Museum of Mineralogy, Baia Mare. Photo: P. Zhokhovsky, P. Timko

Exhibit from the Museum of Mineralogy, Baia Mare. Photo: P. Zhokhovsky, P. Timko

We see that our Christians at all times have been baptized, married, confessed, and communed, and have always sought reconciliation with God. Such is the peculiarity of our Romanian people. Our Romanian nation found refuge precisely in the Church, because the Church is both a school and a tribunal; a place of worship and all their hope and joy and pain.

—Where do you find the strength for everyone?

—My dear, the strength for everyone comes from the need of each one individually. And then I don’t tell him too many things or read too much to him. I don’t work miracles, and like every man, in the end I’ve arrived at old age. If I go, for example, to the Holy Mountain, or to Jerusalem, or to a monastery, to Rarău, for example, I leave there changed—they have a wonderworking icon of the Mother of God there. Or I go to see an elder, like Elder Benjamin, the father abbot, with whom I still speak . He tells me something and I tell him something else. I need this spiritual recovery two tothree times a year.

Wonderworking icon of the Most Holy Theotokos at Rarău Monastery, 1538

Wonderworking icon of the Most Holy Theotokos at Rarău Monastery, 1538

I also go into seclusion, or to Nechit Monastery, and I find Fr. Zosima the younger there, Fr. Nectarie, or I find someone else, and so I fill up my resistance file that way.

—Is there anything you can learn from the young?

—Sometimes you can learn much more from the young than the elderly, because old age does not always bring c wisdom. There are things that I ask the young people here in these years of mine: “What do you think about such and such a thing?” “I figured I had to do this and that.” “Is that good? Tell me, my dear.” “Yes, it’s good, but look, it seems to me it’s also like this, as I think.” And I really take it for granted, that it’s the grace of God that works, not man.

It's all about the spiritual life. An elder in a monastery or a priest among the faithful is a chosen person, he is honored by the people; and know, that the grace of God is present there. The abbot may make a mistake, your spiritual father may make a mistake, but if you render obedience, then his mistake is nothing. You must act in obedience to him, because he doesn’t bear responsibility here, but the Spirit of God, as far as it is given to him at a certain moment for a Christian coming to him. Therefore, there is an absolute need for obedience in the life of a monastery and the life of Christians.

Even if someone says, “Ah, but I don’t go to see that priest. I heard that he’s such-and-such. And I myself saw how at some party, a Baptismal party, he made some kind of strange gesture.” No! That’s not the point. We need to know that this is a man chosen by God, and we must listen to him. His mistake is my elevation. The Holy Fathers say: “Rather than rising on my own opinions, it’s better to go lower with the opinions of an advisor.”

So this is my word about the equilibrium of Christians with a spiritual father. And of course, people go to see them. “Oh”, they say, “there’s an elder at Petru Vodă Monastery!” They print an article in the paper and people say,“Oh, wait, we’re going there!” And what’sthere? I’m sitting here like a fool healing my bones, and my sins too. What can I say? A man is satisfied like that, because an Orthodox Christian par excellence is obedient!

He has a principle, it’s inborn in him; from childhood he was brought up in such a way that as soon as you start talking to him, he says: “I’m sick, I’m broke, I have no income, I’m married, I have two kids, my wife left me.” “And do you have a spiritual father? An advisor? Do you still confess? Do you still take Communion? Do you still go to church?” “Yes, from time to time, Father.”

But this is precisely the key to resolving a man’s difficulties in life.