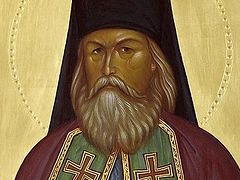

St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov) When some people in the Church become interested in liberalism and reforms, expressing their dissatisfaction with the Church’s traditions, it would not be superfluous to remind them that that is precisely how Protestantism was born in its time. What Protestantism leads to, and its hidden essence is something that the holy fathers reveal to us most precisely. Amongst the fathers of the Church, especially significant is St. Ignatious (Brianchaninov) [commemorated today], whose spiritual intuition always exactly exposed the most subtle deceptions.

St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov) When some people in the Church become interested in liberalism and reforms, expressing their dissatisfaction with the Church’s traditions, it would not be superfluous to remind them that that is precisely how Protestantism was born in its time. What Protestantism leads to, and its hidden essence is something that the holy fathers reveal to us most precisely. Amongst the fathers of the Church, especially significant is St. Ignatious (Brianchaninov) [commemorated today], whose spiritual intuition always exactly exposed the most subtle deceptions.

Being in society and having experienced the influence coming from the Protestant West, St. Ignatius often spoke out on this issue. In the present time, now having the complete works of St. Ignatius, we are able to compile a sufficiently clear picture of his views on Protestantism.

In talking about the nature of Protestantism, which gave birth to a multitude of professors-theologists but not a single saint, St. Ignatius made the following evaluation: “The Protestant is coldly intelligent”,1 that “earthly character”, having nothing in common with Heaven.2 The rationalism of Protestantism, pettily researching the letter of Scripture and not noticing its profound essence, always hindered serious spiritual life. Discussing the Karelians on Lake Ladoga in the article, “A Visit to Valaam Monastery”, the saint next talks about the Lutheran proselytism among the local population, as a result of which Orthodoxy on the Finnish shore was pressured to leave. “Now there are Lutheran churches here, which pronounce only the meagre sermons of a cold pastor. Telling the people in his sermons nothing more than superficial, scholarly information about the Redeemer and His moral teaching, he gives each time something like a funeral eulogy over the true, living faith and Church that the people in these regions have lost.”3 Thus, there is no true faith and life in Protestantism, only rational scholarship with a superficial moral teaching. Therefore, in Protestantism there could never be any serious ascesis, or deep spiritual experience.

Moreover, rationalism, and the absence of a deep spiritual life led Protestantism to the rejection of ascetical principles that have been natural to traditional Christianity over the course of a millennia and a half. To some extent, Protestants, just like godless atheists, blaspheme monasticism, denying its divine origins.4 Such denial was directly embodied in the life of the progenitor of Protestantism—Martin Luther—and was later expressed in Protestantism’s rejection of the Church’s corresponding dogmatic statements concerning the Ever-Virginity of the Mother of God: “Protestants, the sworn enemies of New Testament virginity, assert that the Most Holy Vessel and Temple of God, the Mother of God, violated her virginity after she had given birth to the God-Man, became a vessel of human lust, entered into a relationship with Joseph as his wife, and had other children. A horrible thought! A thought both beastly and demonic! A blasphemous thought! It could only have been born in bowels of profound depravation! It could only have been pronounced and be pronounced by a desperate and outlawed adulterer! It can only be accepted and assimilated by those who have fallen so far from the image and likeness of God to the likeness of beasts, that they have and are only capable of having an understanding of human nature exclusively in in its degraded, animal-like state… Luther, who threw off his own monasticism and took a nun who also cast off her monasticism as his lover—the union of Luther with Catharina Von Bora cannot be understood any other way, because it is not seen that the vows of virginity that they both gave to God were ever returned by them—cries out against Christian virginity. All Protestants cry out against them together with Luther. They call virginity unnatural, against the will, blessing, and commandment of God.”5

St. Ignatius did not even consider the path to Christian perfection to be outside of virginity, chastity, and monasticism. It was a path that was shown in the life of Christ Himself, and was embodied already by the first generations of Christians. Protestantism, in rejecting this foundation of Orthodox asceticism, was naturally regarded by the saint as a fall from a spiritual and moral height to a level of life like that of beasts. “Luther’s writings are unendurable not only for the pious reader, but even for a decent reader. They breathe the crudest depravity and wildest blasphemy… Lutheranism provides more pleasure to the person who desires to turn as rarely as possible to God, and to limit his fleshly desires as little as possible.6

In the complete works of St. Ignatius is published a brief writing entitled, “Lutheranism”, composed of questions and answers. The saint views the birth of Protestantism in the person of Luther as something absolutely unnecessary for people’s salvation. “If Christ’s teachings were sufficient for people’s salvation for fifteen centuries, then what is Lutheranism for? If one accepts Luther’s teaching necessary, then by this very acceptance one is compelled to accept that the original teaching of Christ’s Church was not enough for salvation—which is an obvious absurdity and blasphemy.”7

Although Luther’s writing was directed against a series of errors of the Roman church, St. Ignatius finds three kinds of error in Luther himself. First of all, in place of the Roman errors Luther offers his own errors; secondly, he kept certain of Catholicism’s errors; and thirdly, he even magnified some of Roman Catholicism’s error.

Among the preserved errors of Catholicism, St. Ignatius distinguishes: the teaching of the Filioque (which, in the saint’s view, was the main reason for the West’s separation from Christ’s Church) and the performance of the sacrament of Baptism through pouring [as opposed to immersion].

Among the magnified errors of the Latins, the saint directs our attention to the relationship towards the Eucharist: If Catholics lost the sacrament of the Eucharist by taking out the invocation of the Holy Spirit and the prayers of transubstantiation, then “Luther, rejecting the Eucharist altogether, says, ‘The bread transubstantiates in the mouths of those to partake of it with faith!’”8

Martin Luther The saint sees Luther’s own errors in the following. Having rejected the lawful authority of the Roman popes, Luther rejected also the lawful rank of the episcopate and ordination itself, having by this violated what was established by the Apostles. Having rejected indulgences, he rejected also the sacrament of Confession. The saint points out one of Luther’s key errors: preferring faith with the rejection of good works, saying that supposedly, “faith is sufficient for salvation, even though one’s works do not correspond to faith.”9

Martin Luther The saint sees Luther’s own errors in the following. Having rejected the lawful authority of the Roman popes, Luther rejected also the lawful rank of the episcopate and ordination itself, having by this violated what was established by the Apostles. Having rejected indulgences, he rejected also the sacrament of Confession. The saint points out one of Luther’s key errors: preferring faith with the rejection of good works, saying that supposedly, “faith is sufficient for salvation, even though one’s works do not correspond to faith.”9

Naming Luther’s well-known errors—rejection of icons, holy relics, prayers to the saints in Heaven, most of the Sacraments, and Tradition itself by a false interpretation of the Holy Scriptures according to one’s own whims—the saint concludes, “All of these errors, taken together, are not only in opposition to the one true Holy Church, but also contain in themselves many serious blasphemies against the Holy Spirit!”10 That is, this is not simply a personal opinion with which we can tolerantly agree, but a serious blasphemy against the Holy Spirit.

Thus, we do not find in St. Ignatius’s writings even a hint of any remaining grace outside of Orthodoxy. The saint does not see any possibility of salvation within Lutheranism.11 For St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov) himself, the borderline between true teaching entirely corresponds with the boundaries of Orthodox confession, and the grace of the Holy Spirit dwells only there, where the truth is—in the Orthodox Church. As opposed to modern ecumenist ideas, St. Ignatius was not afraid to call Protestantism a soul-destroying, heretical host: “Many millions of Protestants have used and continue to use the most-divine Gospel for evil, for their own destruction, interpreting it incorrectly and impiously, and are as if moving away from unity with the Universal Church, forming a separate, soul-destroying heretical assembly, which they dare to call the Evangelical Church.”12

Heresy leads to destruction. Therefore, the saint always recalls Protestantism in the context of general decline and corruption that was being propagated in the Russian Empire:

-

“We of the Orthodox faith, viewing it and the Church from the vantage poin of ideas brought on by depravity, Protestantism and atheism were the cause for stealthily and forcibly introducing ordinances into the Orthodox Church that are outside, alien, and hostile to the spirit of the Church, and against the canons and teachings of the Orthodox Church.”13

-

The monasteries are corrupted by the pride and ignorance of various “thinkers”, who “think” and act according to the elements of Western Protestantism and atheism.”14

-

“It is obvious that apostasy from the Orthodox faith is widespread among the people. Some are openly atheist, others are deists, others are Protestants, others are indifferent, while yet others are schismatics. There is no treatment for this wound, no healing. May he who is saving his soul, save it!”15

It is telling that St. Ignatius places Protestantism next to atheism, like a certain preliminary step on the path towards ever greater apostasy from God.

In coming out against the Roman Church, Protestants “exchanged evil for evil, error for error, abuse for abuse;” they trampled upon, rejected, and distorted Divine ordinances.16

Accordingly, the saint called to question the developed practice of receiving new converts, according to which those who came from Protestantism to Orthodoxy were generally received without Baptism. In December 1838, St. Ignatius wrote to St. Leonid (Nagolkin), the Optina elder, a letter in which among other things he wrote, “I have a most humble question for you: Please tell me whether in Moldavia and Vlachia they re-baptize Lutherans and other Protestants, and why. Much is now being said here on these subjects; the Ober-Procurator is especially very zealous for Orthodoxy, and is publishing the canons of the Ecumenical and Local Councils, for our Rudder contains largely not the canons themselves, but interpretations under the name of canons and other very extensive interpretations on these brief interpretations. Grant, O Lord, that having received the true canons in printed form, we might at least somewhat raise our weakened hands for action.”17

As could be supposed, the saint’s search for precedents on the practice of Baptism of former Lutherans proceeded from his thoughts on the existence of a practice in the Russian Church of receiving Lutherans through Chrismation alone. The saint himself, having an idea of the total loss of the Holy Spirit in Protestant communities, most likely was coming to the conclusion that it is impossible that they have any [valid] sacraments, including Baptism (incidentally, the saint’s thoughts on this theme have been lost).

We have at our disposal the answer of St. Leonid of Optina: “As to your question concerning whether in Moldavia and Vlachia Lutherans and other Protestants are re-baptized, I can only say that I heard from the elder Fr. Theodore, who lived there a rather long time, that they do re-baptize; but why exactly I cannot say, for I never had the opportunity to discuss it with him in more detail. But since the discussions arising these days on this subject are related to dogmatic topics, and inasmuch as there is some perplexity, then is it not possible to use some means for the publication this year of a booklet of Royal and Patriarchal Grammotas, shown on the fourth page? By the way, this should all be committed to the Head of the Church, our Lord Jesus Christ, and we should pray to Him about it, that He might preserve His Church in purity, with all the beauty of Her Orthodox confession, and suggest to those pastors holding Her rudder to guard Her in safety as a firm stronghold, through the publication of very clear and reliable canons of the Councils. May He grant us the will and strength to fulfill them, and acquire to the measure of spiritual maturity the will of Christ.”18

Compared with Catholicism, St. Ignatius views Protestantism as a greater fall. If the Catholics made changes to the sacrament of Confession, the Protestants rejected it outright.19 If the Catholics excluded the invocation of the Holy Spirit from the Liturgy, “the Protestants have rejected the Liturgy altogether.”20 In Catholicism, there is still an element of ascetism, albeit spiritually delusional, while Protestantism has completely lost the ascetic life; remaining is only soullessness and cold rationalism. As we know, St. Ignatius relied upon asceticism, based upon the writings of the holy fathers, for his entire spiritual life; he saw in it a pure and clear path to salvation. Therefore, he especially sharply commented on Protestantism’s disgust for patristic ascesis. Thus, the saint evaluates Protestantism as the loss of the key institutions of Christianity—a kind of foreshadowing of the ultimate loss of them in atheism and godlessness.

Nevertheless, it can’t be said that the saint despised Protestants themselves. The toughness and categoricalness of his statements were always explainable by the obvious fact that any departure from the truth in Christ, which is manifested in Orthodoxy, is a departure from salvation; moreover it is an unnoticeable departure and therefore more dangerous. The saint’s bitter feelings regarding the spread of heterodox teachings was bitterness over the spread of seductive lies, which conceal the truth. But the saint never expressed any contempt for Protestants themselves.

For example, he had a very warm relationship with a famous artist who was a Protestant by confession—Karl Pavlovich Bryullov (1799–1852). Despite the secular character of his main works, Bryullov often filled orders from churches. For instance, Bryullov painted an image of the Holy Trinity for the St. Sergius Hermitage located near St. Petersburg, where St. Ignatius was the superior. Extant is a letter from St. Ignatius to Bryullov, which shows the heartfelt warmth of feeling he had for the artist. “I have always had a warm sympathy for you. Your soul seemed to me as one wandering lonely in the world. I also wander this way, surrounded by difficulties from my childhood …”21 The saint strove not to wound the artist’s soul, saying of his creative work, “I have long seen that your soul seeks the beauty that would satisfy it, amidst earthly chaos. Your paintings are an expression of a strongly thirsting soul.”22 However, the saint politely and tactfully hinted about the need to seek authentic, eternal beauty: “The picture that would decisively satisfy you should be a picture from eternity. These are the demands of true inspiration. Any beauty, both visible and invisible, should be anointed by the Spirit; without that, the anointing upon it is the seal of corruption; it (beauty) helps to satisfy a person who is led by true inspiration. He needs that beauty to respond life, eternal life. When from beauty breathes death, he turns away from such beauty in disgust.”23 As can be supposed, in the next lines are expressed the saint’s heartfelt desire that Bryullov receive Orthodoxy: “I wish when I arrive to see you healthy and strengthened. And you must live, live in order to become more closely acquainted with eternity, so that before entering it your soul would acquire heavenly beauty; this lofty yearning has always been in your soul. The Heavenly Father’s embrace is always open to receive anyone who desires to have recourse to this holy, saving embrace.”24 Unfortunately, although he associated with a holy man, Bryullov ended his life’s path outside the bosom of Orthodoxy.

On the whole, St. Ignatius’s evaluation of Protestantism might seem to some too categorical and strict. Just the same, it would make sense to heed the saint’s spiritual intuition: The path of rational comprehension of the truths of faith, while having lost the Holy Tradition of the Church, leads to coldness in spiritual life, and without fail to the loss of dogmatic purity, which we often see in our modern liberal reformers.