The village of Ivan’kovo, where God willed me to be born, tucked some distance away from the major roads of the ancient Chernigov-Novgorod-Seversk land, lies comfortably wrapped by the peaceful and soothing landscape of Little Russia. Spread out on one side over a vast plain and framed by fields and mixed forests of birch, pine, and oak, its opposite part stretches over picturesque green ravines, rather steep here and there, but nevertheless densely lined with whitewashed houses, surrounded on their part with orchards and gardens filled to the brim with all kinds of garden crops. Bedecked with four willow-lined ponds, Ivan’kovo was probably about five hundred years old. At least, that’s what the records of the Rykhlov St. Nicholas monastery, to which the village was assigned in 1589, tell us, but there is speculation that it was founded before the Mongol invasions.

Its name has always sounded somewhat mellow (probably because of the soft sign1 in the middle of the word), something really familial, of your own; but it could also be because my father and two grandfathers all happened to be named Ivan. In every part of the vast Slavic-Russian land, the diminutive of this name could have varied: Vanya, Ivanko, Ivanya, Ivas’; and I imagined how, in days of old, a certain Ivanko-Ivanya traveled through this area. It was attractive to him, and so he decided to stay here forever. Most likely he didn’t come alone, or he wasn’t the only one called by this name. Anyway, the name worked out quite well, because until recently there were quite a few Ivans residing in the village.

One of the old-timers claimed that the village was founded by the descendants of the Zaporozhye or Don Cossacks, and the name of the Ivan’kovka church confirms it: It was named in honor of the Protection Icon of the Mother of God, which the Cossacks have revered for a long time.

“Candles burning inside the shut down church”

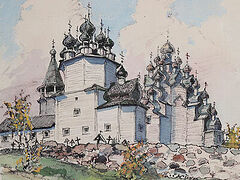

The church was built, as it should be, in the most attractive place—upon the hill in the center of the village—and it was considered one of the largest and most important local churches. My eldest uncle, Alexander, who, as a five-year-old boy accompanied my mother to church services there, vaguely remembered that its iconostasis was very high and unspeakably beautiful. Gifted to the church by “a certain princess”, it was taken down the Desna River on a large raft built specifically for the purpose. Then from Radichev, the nearest landing place, it was taken to the village on a cart driven by a team of six horses. He couldn’t remember any other substantial details about it except that he was quite “taken” by the singing of the church choir.

But his younger brother Timofey, apparently out of nostalgia (as a young man, we had a Komsomol-sponsored trip to the mines in the Donbass, where he started a family and stayed forever), once told me some stories from his childhood. One of them, having to do with the church (and it was of little interest to me at the time), I somehow remembered practically word for word.

The man who climbed up and threw down the church cross was soon the first one of the villagers to be killed in the war that broke out soon after...

“The church has been closed twice,” said Uncle Tima. “The first time was in the 1930s, and the man who climbed up and took down the cross was the first of the villagers to be killed in the war that started soon after... When the Germans entered the village, they reopened the church and the services were held there once again. The Germans, of course, had their own goal for acting this way—hoping to win the support, as they put it, of the local population. But when the Germans were “kicked out” the Communists closed it again. At first it had a huge padlock on its doors, but everything stayed secure inside for a long time. Then, one day, my buddies and I decided to sneak in and take a look. Boyish curiosity. I remember it was so terrifying it gave me the creeps, but we made up our minds anyway and managed to get in through a window located quite high up. What we saw in front of the altar was a candle stand full of burning candles... We were looking at these candles with bated breath but then suddenly we heard someone as if sighing and crying softly. I don’t remember how we ended up back on the street, I think, but we all squeezed through the window at the same time. We came back to our senses somewhere in the school garden and agreed that we would never, under any circumstances, ever tell anyone about it.”

“First of all, we were afraid of being punished by our parents for such mischief,” he recounted his story, ”and, secondly, we decided that no one would even believe such a thing, but would make fun of us instead. Apparently, none of my accomplices broke the pact, because this incredible story was never made public. I don’t know what it was. The last thing I can think of is that a believer came there at night, lit candles, and cried out loud in spite of our intrusion. It was quite an ordeal to get inside—the keys to the door were kept by the local Party members, the windows were too high up from the ground, so it was only us boys who could climb on each other's shoulders to reach it. Personally, I kept the lifelong memory of something truly mysterious and incomprehensible...”

“Rumor had it that the sacred church objects were safely hidden somewhere, maybe buried in the woods, under the oaks..,” my uncle said. “As for the main bell, it had apparently sunk to the bottom of one of the ponds. The last rector of the church, Fr. Petro Ivanovich, lived in the village for some time, earning his living by teaching the children to play the violin and quietly sipping wine out of grief... Then, it seems, his daughter and son-in-law, who was a pilot, took him away to live with them. Or maybe he died in the village and is buried in one of the village cemeteries, I can’t say for sure. So, this priest, Petro Ivanovich, knew exactly where all these sacred objects were hidden...

“But,” concluded Uncle Tima fatefully, “mark my words: One day all this will be needed again and so it will be discovered. You may even live to see it…” he added out of the blue.

“Oh please, don't listen to him,” his older brother Alexander told me many years later in his kitchen in Rostov-on-Don. “He’s a mystic from his childhood!”

An antenna in place of the cross

A village club is still housed within the church walls, or what is now honorably known as the House of Culture. Thanks to its valued purpose (compared to other possible uses), the building is well preserved. It still looks cross-shaped in plan, and, if you put at least a small dome with a cross over the central part of the roof, the whole structure will take on quite definitive features.

A former church still houses the village club, these days honorably called the House of Culture

When I was a child, the horn-like television antenna proudly poked into the sky in place of the cross. My school friend Larka (that’s what her parents called her, followed by the rest of the villagers, from children to the elders, even when she grew up), the cinema operator’s daughter, laughingly told me that on major church holidays, the old ladies from the nearby huts come out into the street, cross themselves and bow down... at the antenna!

It never occurred to her, or to me at the time, that these old ladies knew all too well that the antenna was set up in place of the cross, but they bowed to the cross knowing too well that it was there forever, just like the Guardian Angel, who kept his eternal guard wherever the Liturgy was celebrated at least once. And so he will keep standing on guard there until the Second Coming of Christ, even if that place is defiled and desecrated...

Could it be that it was he, the Guardian Angel, who cried on that night in the closed church...?

Once, on the eve of a great church feast, a prankster heroically climbed on the roof and, risking his life, pinned a pair of white, men’s underpants to the antenna...

But the old ladies, as they came out of their wicket gates early the next morning, continued to cross themselves and bow in reverence.

“It was so funny!” reported the cinema operator’s daughter.

My childhood memories are filled with images of numerous school parties in what seemed then to be the seemingly gigantic space of the club. Here’s the ceiling-high festive New Year’s2 tree, with all of us dancing merrily around it, dressed in the colorful carnival costumes... And here I am, standing on the stage with the school choir, and, as I look up, I see a wreath of soft cherubic faces showing through the white ceiling paint, as if through a white veil.

“They paint them over again and again, with the strongest of oil paints, but they still show through,” Larka told me, eyes wide open.

“It’s practically invisible, if you don’t know or don’t look too hard,” sadly added Valentina, another of my fellow villagers who came to me for a visit.

After returning to my native village, I went to visit my former school friend. After we graduated from high school, Larka learned the trade of a cinema operator and replaced her aging father in the movie booth, and then became the club’s director. Her and her husband’s house stands next to her father’s, just five minutes away from the clubhouse and a small village square with the well in the center. The well is beautifully lined with stone, decorated with a metal roof and openwork edging, and it is fenced with chains on posts. But, just like thirty years ago, it seems to be completely dry. At least, as far as I could remember, no one had ever gone there to fetch water. Its decor had deteriorated, crumbled down, while the posts grew rusty and stood sagging.

They say that wells get covered with silt and dry up—and die if people don’t draw water from them all the time. So, in order to have a supply of fresh and tasty water in the well, one should constantly draw from it. In ancient times, even very rich people deliberately placed their wells behind the fences of their mansions and estates so that as many people as possible could come to them to draw water.

A very interesting analogy with the spiritual “living water”: the more you draw from it, the more you receive, and vice versa. It is probably no coincidence that a dried-up well stands next to a former church; when the church was no longer needed, the well dried up...

To be continued…