What are church schisms and why do they arise? And if the Lord reveals the truth to us to the extent that we can contain it, how do we know which side is right? Since the time of the First Ecumenical Council, the Church has been struggling with this disease, but it keeps coming up again and again.

Where do heresies come from?

The Arian dispute, which split the Church in the fourth century, raged for almost a hundred years, and its consequences were felt even longer. It all began with the arrival in the Church of many educated people who were keenly interested in the kinds of problems that few people cared about previously. And different understandings of the Trinity of the Godhead emerged.

For example, the heretic Sebelius taught that the Trinity is one God with three guises, which He changes, as masks change in the Greek theater, and appears to humanity in one form or another.

The exact opposite was stated by another heresiarch—Paul of Samosata. He believed that there was only one true God: God the Father, and that God the Son and God the Holy Spirit are not fully divine entities. His views have long taken root in the East, especially in Syria. The presbyter of the Alexandrian Church, Arius, also adhered to them. He was undoubtably a bright, talented man, and so popular that the Bishop of Alexandria, Achilles, while dying, even designated him to be his successor. However, he never became a bishop—he was not chosen.

What did Arius think about God? That there is an all-powerful God the Father who is simultaneously present in all forms, at all times… He was always there. But had God always been the Son? Arius strongly doubted this. After all, the Son always appears after the Father. Therefore, He was created by the Father and, like all other creatures, has a created nature. But the Father’s nature is fundamentally different—eternal, Divine. That is, Arius denied the full divinity of Jesus. For this he was condemned in 318 by Bishop Alexander of Alexandria.

“Everywhere are people arguing about the incomprehensible”

Arius fled from Alexandria and sought support from his classmates, among whom were Eusebius of Caesarea, the father of church historiography, and Eusebius of Nicomedia, bishop of one of the imperial residences.

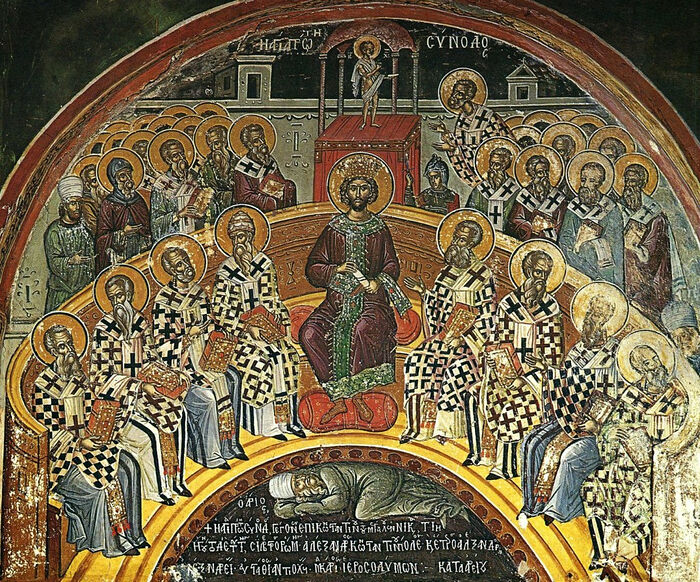

A serious dispute broke out. And for Emperor Constantine, when he decided to support Christianity, it was fundamentally important to preserve the unity of Christians themselves. At first, he tried to convince Arius and Alexander to reconcile and not to raise this dogmatic dispute at all. But in the end, it had to be dismantled. The First Ecumenical Council was convened in 325 in Nicaea, at which most of the bishops condemned the teachings of Arius and adopted the Creed, in which God the Son was recognized as Consubstantial and Co-eternal with the Father.

Arius and several of his followers went into exile. But there Arius did not remain silent for long. After settling in Nicomedia, he expounded his teachings in the Thalia, a book intended for commoners. As a result, theological issues became the domain of street gossip. Athanasius the Great wrote of how Arius’ supporters preached their ideas:

“To this day Arians, not in a small number, still catch young men at the marketplaces and ask them questions, not from the Divine Scriptures, but as if pouring out from the abundance of their heart… Everywhere there are people speculating about the incomprehensible—in the streets, the markets, the crossroads. I ask how much do you have to pay, and they philosophize about the born and the unborn. If you want to know the price of bread, they answer: “The Father is greater than the Son.” You ask if the bathhouse is ready, they say: “The Son came from nothing.”

From these words one can see how deeply the Arian heresy was troubling all Christians at that time. This is understandable—all the people felt that the dispute was not about an abstract theoretical question, but about the very essence of faith.

Most of the local bishops were looking for some kind of compromise. And the emperor himself, at the end of his reign, was inclined to soften the wording of the Council of Nicaea for the sake of uniting the divided Church. He even sent into exile the most zealous supporters of the Nicene Creed, such as Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria. And on his deathbed, he was baptized by one of the leaders of the Arians—Eusebius of Nicomedia.

Incorrect Preaching

The sons of Constantine the Great had different views on church politics. In the West, the Emperor Constans was a pillar of Niceneism. In the East, Emperor Constantius, on the contrary, supported the Arians. Arianism was finally condemned at the Second Ecumenical Council.

But it did not disappear—it spread among the barbarians. After all, the first Christian preachers were sent to the East Germans from the Eastern Roman Empire when Constantius ruled it. It is clear that they preached the Creed in which they themselves believed. Thus, Arianism became the national religion first of the Goths, and then of other Germans. In fact, the Arian dispute was finally resolved only in the seventh century with the transition of the barbarians to Niceneism.

Heresy in the service of Politicians

But the Christian martyrs who suffered during the time of Emperor Zeno of Isauria in the Vandal Kingdom they created in the conquered lands of North Africa—in what is now Tunisia, northern Algeria, northwestern Libya and the islands of Corsica and Sardinia—fell victim not so much to a religious as to a political crisis.

It was under Zeno that the Western Roman Empire was abolished, and Byzantium remained the sole successor of Rome. But Rome was greatly weakened; back in 429, vandals from Spain invaded its African provinces and in 439 took Carthage; in 455 they captured and plundered the Eternal City itself.

But in the conquered territories, especially in Africa, the conquerors—of which were rather few—could not expect a new influx of their compatriots and were very afraid of assimilation with the local population. Roman Africa, the second most developed region of the empire after Italy, was almost entirely Christian by that time, and mostly Orthodox Christian, which significantly complicated the Vandals’ development of it.

So, they chose the win-win tactic of “divide and rule,” pitting Arians and Niceans against each other. But the local Orthodox population, who at first mistook the Vandals for deliverers from Roman oppression, quickly grew cold toward them because of religious persecution.

“But a brother will betray his brother to death.”

When Emperor Zeno in 480–481 demanded from the Vandal king Gunderic to fill vacant episcopal posts in Carthage, he in response demanded equal rights for the Arian church in Constantinople and other eastern provinces. And if Byzantium did not agree to these terms, Gunderic threatened to deport all Orthodox bishops of the Vandal Kingdom “to the Moors.”

Relations between the Vandals and Byzantium worsened, and a severe persecution of Orthodox Christians began in North Africa. The edict promulgated by Gunderic required the conversion of all Christians to Arianism no later than June 1, 482. Those who did not want to obey were burned at the stake or otherwise executed. The Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea, and St. Isidore of Seville, call Gunderic the most cruel and unjust persecutor of Christians in Africa.

St. Victor of Vitena, an eyewitness of the repression, wrote in the late 480s:

“If a writer tries to add to the story at least some detail of what was happening in Carthage, even without stylistic embellishments, he will not be able to even name the names of the tortures. All this is still before our eyes today, and everyone can see some without hands, others without eyes, others without legs; some have their nostrils torn out and their ears cut off, others have their heads, previously proudly raised, pressed into their shoulders as the executioners, tugging at the ropes with all their might, pulled them up over the houses and swayed the hanged man back and forth. Sometimes the ropes tore and some people fell down from this height with a terrible blow, while others, having broken all their bones, could not recover for a long time, and many soon expired.”

So, when the barbarians broke into the temple where the faithful had gathered for the secret Liturgy, many of those praying fled. But 300 people voluntarily gave themselves up to torment and were beheaded. And of the sixty-two priests two were burned to death, and the rest had their tongues cut out.1

And Arianism—renamed Unitarianism in the eighteenth century—has survived to the present day as a small number of sects.