An icon is called “theology in paint”, and therefore we decided to look at the iconography of the twelve major feasts with a person who studies it not just theoretically, but experientially. Iconographer Anatoly Alyoshin, a teacher at the iconography faculty of the Moscow Theological Academy, one of the leading experts in the field of fresco painting, reflects on the iconography of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos.

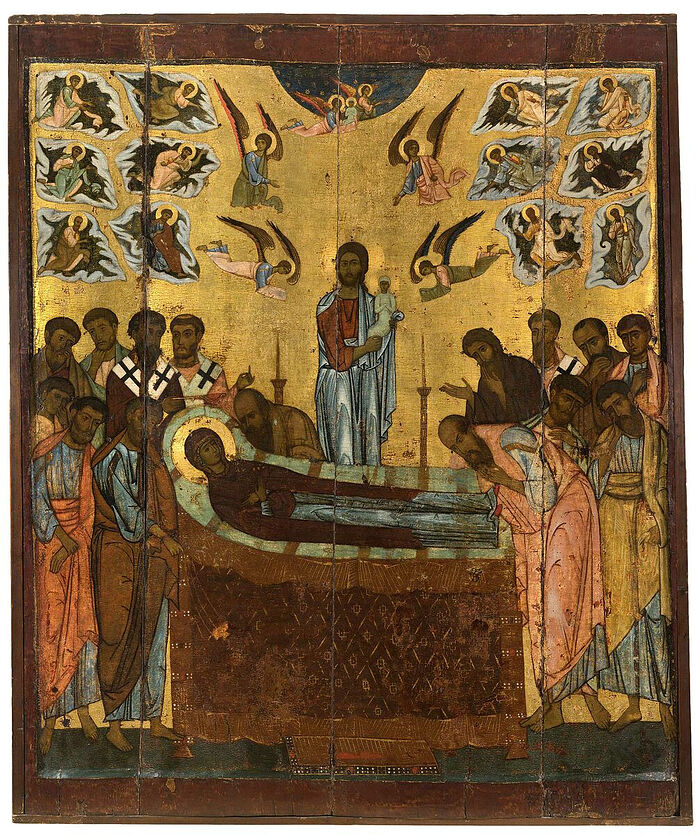

—Let’s talk about a more concise version, such as the fourteenth century icon from the Novgorod State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve.

—Looking at the icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God, we can say that the event is very clearly depicted here. We see in the center a bed on which the most-pure body of the Mother of God rests, surrounded by the apostles who have “flown” from different parts of the earth, and the Savior holding the soul of the Theotokos in his arms.

It should be noted that in comparing death with the Dormition, with sleep, the concept of death as a dream is traditional for the Church. The Christian faith presupposes not just the expectation of the end of the world and the universal resurrection, but the desire for this event. “I look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the age to come,” says the Creed. It occurs more than once in the Gospel—for example, the Lord Himself said of the daughter of Jairus, do not cry; she is not dead, but sleeps (Jn. 8:52), and about Lazarus, Lazarus, our friend, has fallen asleep (Jn. 11:11).

Even more is the comparison with the Dormition logical when it comes to the Mother of God. Let us recall the words of the stichera and the Irmos of the ninth Ode of the canon for the Vigil of the feast:

“The angels, having beheld the Dormition of the Most Pure One, / were struck with wonder, // at how the Virgin went up from earth to heaven.”

“In thee, O Virgin without spot, / the bounds of nature are overcome: / for childbirth remains virgin / and death is betrothed to life. / O Theotokos, Virgin after bearing child and alive after death, // do thou ever save thine inheritance.”

The same thought sounds forth in the troparion:

“In giving birth thou didst preserve thy virginity; / in thy dormition thou didst not forsake the world, O Theotokos. / Thou wast translated unto life, / since

thou art the Mother of Life; // and by thine intercessions dost thou deliver our souls from death.”

On the icon around the bed of the Mother of God, we see the apostles who came to say goodbye to Her. The liturgical texts emphasize that just as the apostles came to the bedside of the Mother of God from different parts of the earth, so we also come to the Church, to the liturgy—each from his own situation, to put it in modern terms. In unknown ways, the Lord gathers His flock to the throne. And the apostles are in groups on the edges of the bed—as on the edges of the throne: on one side is Peter, on the other side is Paul (who is present in all significant events, in which, if viewed from a human, historical point of view, he did not participate; but in icons there is a completely different dimension)…

Behind the bed stands the Lord with the soul of the Mother of God; so in the Liturgy He stands invisibly, being the Center and the Performer of the sacrament.

The soul of the Mother of God is depicted as a swaddled infant, suggesting that the transition to Eternal Life also takes place as a birth.

In some versions, the gates of the Kingdom of Heaven are depicted, and the Mother of God ascends to these gates by angels in Her usual form (not in the image of an infant).

—Which saints are usually depicted on the icons of the Dormition?

—Those who, according to tradition, were present at the Dormition—James of Jerusalem, the brother of the Lord, Dionysius the Areopagite, Hierotheus of Athens and Timothy of Edessa.

—What role does the image play of angelic powers surrounding the mandorla (radiance), inside which is Christ with the soul of the Theotokos?

—Every good deed, especially a sacred one, happens only with the help and in the presence of angelic powers. So, on the icon of the “Dormition of the Mother of God” they are depicted delivering the apostles and carrying the Mother of God to the Kingdom of Heaven, standing reverently with candles around the bed of sorrow.

Here we can also speak about the liturgical meaning—the Liturgy involves the clergy, the people who have come, the Heavenly Powers, and, of course, the Lord Himself. The whole Church in its fulness is present. This fullness is also emphasized here. The Apostle Peter is usually depicted with a censer. He censes the bed, as they cense the throne in the temple.

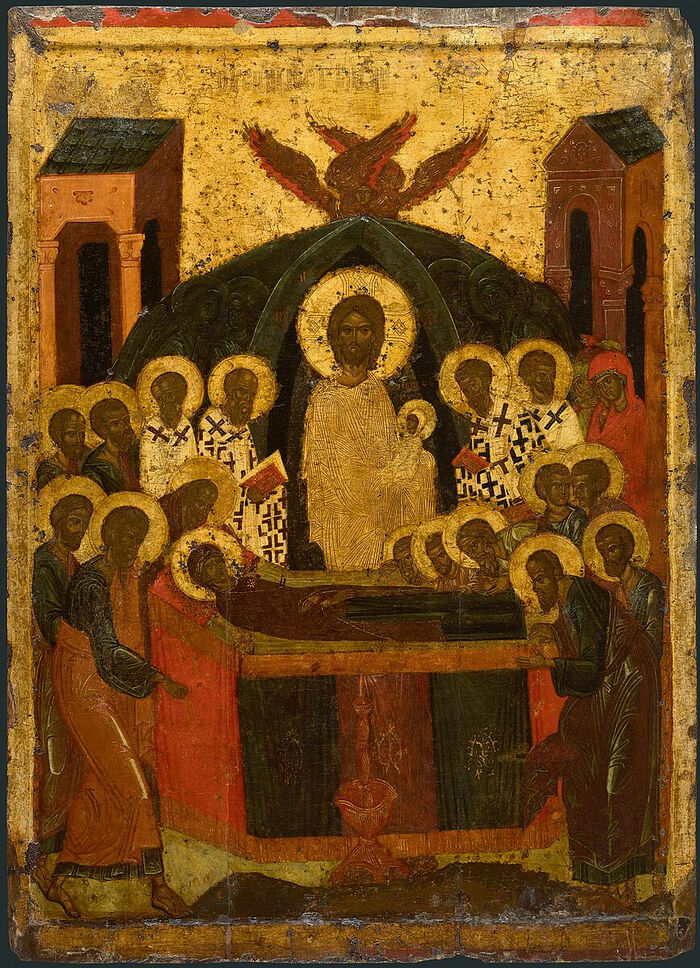

Even if there is no mandorla with angels, as, for example, on the thirteenth century icon of the Dormition of the Theotokos from the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery [Moscow], angelic hosts are still present: there are flying angels with covered hands, signifying that they are close to the Holy Place. Above them are two belted angels, also pointing to the Savior with the soul of His Mother, and above them are two more angels who carry the soul of the Theotokos to Heaven.

—There is a candle burning in front of the Virgin’s bed (on this icon —one, maybe two)…

—According to tradition, the Mother of God Herself instructed that a candle should burn in the upper room. But there is also a liturgical note here—candles are lit before the royal gates.

I would like to say that in Russia the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God has always been very important for believers. Both in the ancient iconostases and in the templons of large temples, the image of the Dormition was not left out. This icon, as a rule, completes the festive series. The importance of the feast for the Russian Church is confirmed by the numerous Dormition churches... The ancient one built by Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky in Vladimir in 1158. Or the Dormition Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin (147–1479), which is so important for our country and its history.

The Russian and Balkan traditions are also characterized by the frequent depiction of the Dormition on the western wall of the church; that is, it is the image that the parishioner sees last when leaving the church. There is also such a stable tradition of the composition of the Dormition of the Mother of God being depicted on the northern wall, opposite the composition of the Nativity of Christ. This parallel has all the same liturgical meanings—that is, the Liturgy is like a common divine service: in the Nativity of Christ, both people and angelic hosts came to the Savior Himself, to His manger; and in the composition of the Dormition, everyone came to the bed of the Mother of God. But as we have already said, the figure of Christ is central here.

The Apostles flying on clouds

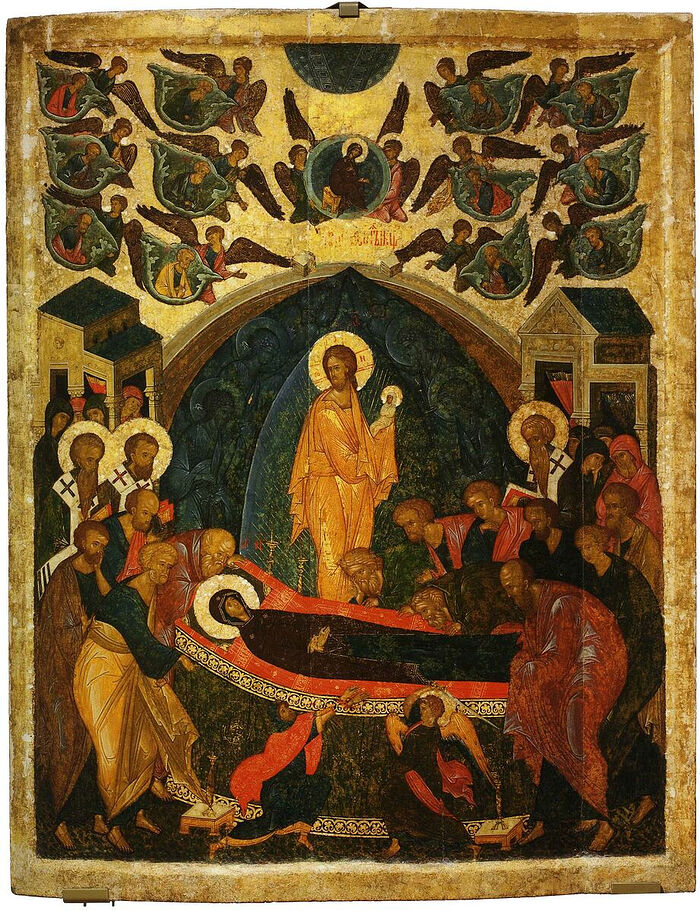

—Now let’s talk about the “Cloud Dormition.”

—The “Cloud Dormition” is, so to speak, an expanded version of this feast. The apostles are depicted not only at the bedside of the Mother of God, but also in the upper part of the icon, on clouds, flying from different parts of the earth to Jerusalem. This miraculous movement of them is emphasized visibly, and, according to the tradition of the Church, this is how the Lord gathered them together once again at the bedside of the reposed Theotokos. And the liturgical meaning remains the same: the Lord gathers people from all over the world to worship.

—We haven’t spoken yet about the architectural structures on the icon. What meaning do they carry?

—They show that the action takes place indoors (we remember that this is the upper room on Mount Zion in Jerusalem). If the action takes place outside the premises, outdoors, hills are usually written.

—Let’s return to the more detailed versions, in which we can see the episode of the presentation of the Mother of God’s cincture to the Apostle Thomas, who, according to tradition, was carried to the bedside of the Mother of God belatedly and received the cincture from Her hands.

—This tradition supplements the basic facts and the basic, primary thing depicted in the icon. That is, it adds narrative, the desire to depict the event in more detail. The same function is performed by another episode, which illustrates the moment when the Jewish priest Avfony treated the Theotokos inappropriately by touching the bier to throw off Her body. An angel cut off both his hands. But when, after the admonition of the Apostle Peter, Avfony prayed for help, he regained his hands in one piece. We see this, for example, on the icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God circa 1497. It comes from the local row of the iconostasis of the Dormition Cathedral of the St. Cyril of Belozersk Monastery.

In the Dormition Cathedral of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos is executed, to put it in modern terms, as a storyboard; that is, each of the moments of what is happening is depicted in several registers of the painting. It is a colossal labor for an iconographer to depict the Dormition step by step. The purpose of this multiple depiction of the Dormition, I think, was the desire to fill large areas of the walls in a meaningful way, and so that the person contemplating the murals could imagine as best as possible what was happening then, at that moment, as if he himself were a witness.

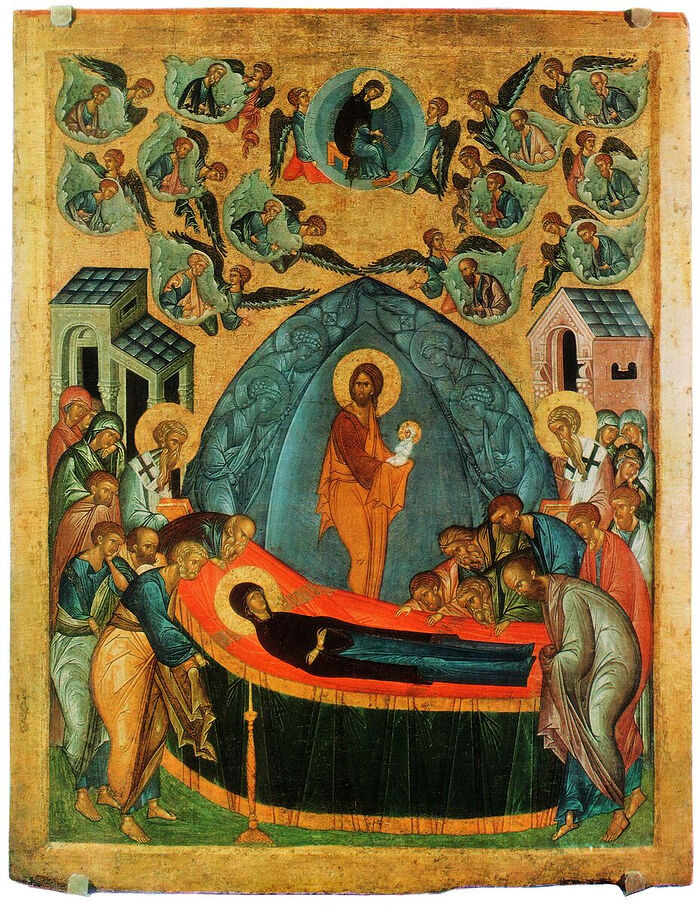

In my opinion, the icon of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos of the fifteenth century Tver origin from the Tretyakov Gallery deserves attention. The iconography is “Cloud Dormition.” The icon is very beautiful in color. It is often copied by students at our iconography faculty. The exquisite color structure of the icon attracts attention.

—Why do you think the composition of the mature iconography of the Dormition belongs to the post-iconoclastic era?

—Indeed, many iconographies take shape in this era, and not by chance. The Church began to pay special attention to both iconography and the language of iconography. In whose person did this take place? First of all, it was the saints and the venerable ones; and I think the iconographers themselves also shaped iconographic traditions.

—In the icons of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos, we see the sorrow of those who gathered at Her bedside. At the same time, there is never despair....

—Yes, it is sorrow, light sadness, but never hopelessness—because iconography does not accept this. There is always hope for Eternal Life in icons. Yes, the Apostles and everyone who knew the Mother of God cannot help but feel purely human feelings at parting with Her here on earth. But they know that Christ is risen. And in general, this conveys the character of the entire iconographic narrative: the presence of the Savior, Who holds the soul of the Mother of God in His hands, and the angels who lift Her up. It is no accident that the Dormition is called the Pascha of the Mother of God. According to the tradition of the Church, the Theotokos was taken to Heaven with soul and body.

In this is the great mystery and our hope. That is why we will never see anything gloomy in the color scheme of the icon of the Dormition—there will always be jubilant colors.

—Tell me, did you paint the Dormition of the Mother of God icon yourself?

—Yes, I painted the composition of the Dormition of the Blessed Theotokos several times, and mostly on walls. For example, in Cherepovets, in the chapel of St. Philip of Irap, 1999, one of the petals of the vault was dedicated to the Dormition of the Mother of God. In the Pakhomiev-Nerekhtsky Monastery, in the Holy Trinity Cathedral, 2005, in the Krasnodar Region, Argatov village, the church of St. Prince Vladimir, 2015.

When I am working on this subject, it is important for me to depict the feast, the triumph of life over death—because if you go back to lines of the stichera, “In thee, O Virgin without spot, the bounds of nature are overcome”, it conveys that the true purpose of man is Eternal Life, to abide with God in Eternity. The whole dramaturgy of the icon has already been revealed, the artist can only interpret it one way or another: Do the apostles grieve in thought, or do they grieve and communicate with each other, for example.

I try to read the liturgical texts before starting my work. There are two canons for the Dormition of the Mother of God—those of St. John of Damascus, and of St. Cosmas of Mayum. These hymnographers, although they were brothers, can be said to be different in style. In St. Cosmas, the meaning turns in complicated ways; it needs to be read, delved into. To understand the meaning, you often have to go back to the beginning of the troparion. For me personally, the lines of St. John’s canon connect the mind and the heart, and you perceive what you read not only with your mind, but you also get some kind of spiritual impulse. Both canons are very interesting, and it is necessary to read them both, because you get food for the mind, for the soul, and for spiritual reflection. These hymnographers show us on a high spiritual level what thoughts and feelings can be born when we comprehend the theme of the Dormition of the Mother of God. And this helps a great deal in the work of writing the composition of the Dormition, filling it with content.