The Orthodox liturgical tradition is very, very old, and still retains vestiges that reflect much older circumstances. For example, immediately prior to the Eucharist proper the deacon cries out to the doorkeeper, “The doors! The doors!” That is, he is telling the doorkeeper to close and guard the doors lest the Roman soldiers break in and arrest them all for what the Roman law considered a capital offense—viz. attendance at the Christian Eucharist. Never mind that the office of doorkeeper no longer exists and that the pagan Roman empire (with its hostile soldiers and hostile laws) is long, long gone. Orthodox are a liturgically conservative lot, and the deacon still issues the old directive to the doorkeeper.

It is the same with the dismissal of the catechumens after the first part of the service. In the old days, catechumens were not allowed to attend the Eucharist proper, and so were kicked out and sent home after the first part of the service. They were there for the Scripture readings, the sermon, and the litany and prayer for them offered by the celebrant. But after that, as part of the disciplina arcani which protected the Eucharist from profane non-Christian gaze, since they could not offer the intercessory prayers, exchange the Peace, or commune, they were dismissed and sent home. Now of course they are allowed to stay for the entirety of the service, along with any casual visitors (something unthinkable in the early church), and so they stay put until the end of the service—and also for the coffee hour which usually follows. Nonetheless, in many places (though not at our St. Herman’s) the deacon still tells the catechumens to depart and go home after the litany and prayer for them.

We see this same liturgical conservativism in references to pagan practices, such as in the references to “the delusions of idolatry” or one’s “former delusion” in the anaphora of St. Basil and in the baptismal prayer for the making of a catechumen respectively. The “former delusion” which the would-be catechumen was then forsaking was of course the delusion of idolatry—the erroneous notion that many gods existed and that it was a pious thing to worship them.

We also see this conservatism in liturgical references to paganism itself. At the end of the anaphora of St. Basil (who died in 379) the celebrant prays that God would prevent schisms among the churches and “pacify the ragings of the pagans”. At Lenten Matins the reader asks the heavenly King to confirm the Faith and “quiet the heathen”. It was understood by all the faithful when those prayers were first used that the pagan heathen did a lot of noisy raging against the Church, so that the Church had to ask for God’s protection against them.

It is easy to forget all that raging now, and how perverse and impious Christians once seemed to the mass and majority of pagan society. We can scarcely imagine this now in our secular society where religion, if it is tolerated at all, is pushed to the margins and relegated to the private and personal sphere. (I apologize to any in the Bible belt where this is not so; please remember that I live in godless Canada.) In ancient Rome, temples were everywhere, and the gods lived side-by-side men inhabiting the same world. Our modern distinction between “religious” and “secular” was inconceivable back then. Decency, piety, good citizenship, and respectability consisted of giving all the gods their due, and the gods, in return, would bless and protect society.

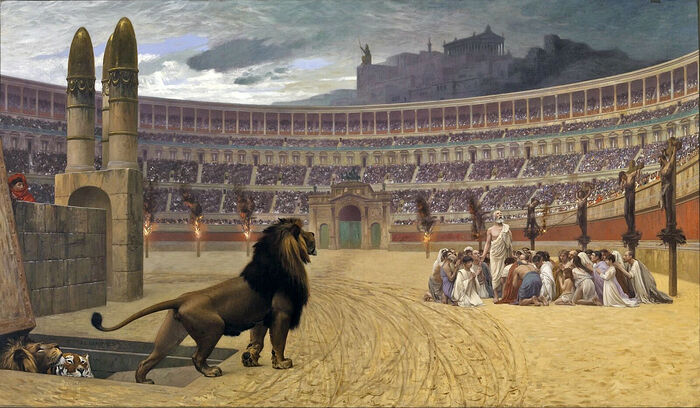

Given this symbiotic arrangement, the Christian insistence that those gods were not real gods at all, but demons struck most people as crazy and even dangerous. What retaliation might come from the gods if people stopped worshipping them and even denounced them? War, famine, pestilence, drought, flood? The Christian refusal to connect with the gods almost meant the Christians’ complete separation from their neighbours: pagan stories (i.e. myths) were everywhere and formed the foundation for the educational system, and much of the meat in the local market had been sanctified by being offered to the gods. Given this omnipresence of the gods in society one could scarcely have avoided contact with them if one wanted to. No wonder the pagans raged against us.

Tertullian, a north African apologist, documented much of the raging: the pagans “take the Christians to be the cause of every disaster to the State, of every misfortune of the people. If the Tiber reaches the city walls, if the Nile does not rise to the fields, if the sky doesn’t move [i.e. in a drought] or if the earth does [i.e. in an earthquake], if there is famine, if there is plague, the cry is at once: ‘The Christians to the lion!’ What, all of them to one lion?’ (from his Apology, chapter 40). In the old days, pagan opposition was constant and real.

But, one might ask, why keep such liturgical stuff around (such as the instruction to guard the doors and the references to the pagans) so many years and centuries later? Here at St. Herman’s I have always defended the retention of the directive about the doors because one never knows when hostile people might try to enter them again. (This is not paranoia; as recently as the Covid crisis here in B.C. police were instructed to enter churches which remained open and shut them down. Like WKRP Dr. Johnny Fever once said: “When people are out to get you, paranoia is just good sense.”)

And the pagans are still around (at least here in Canada) and they are still noisily raging. They are not dead or even asleep. They are wide awake (and ‘woke’). They don’t worship Zeus or Apollo anymore. The idols currently ascendent here in the West have different names. But like Zeus and Apollo in the old days, our modern idols are everywhere and are powerful. As those who have fallen afoul of their worshippers have lately discovered, the lion still exists too, in the form of being “cancelled”, and perhaps even fines and imprisonment. Apparently there are all sorts of ways of being devoured.

Some hopeful people have suggested that this approach is too negative, shrill, and unjustly paranoid. They say that this is making a mountain out of a mole-hill, and anyway the pagan raging will stop soon enough. The current unpopularity experienced by visible and vocal Christians here will not last. It is a mere swing of the pendulum, one which soon enough swing back the other way.

Amen; may it be so; may our current Canadian situation be the swing of the pendulum and not, as I suspect, the leavening of the lump (see 1 Corinthians 5:6). But until things change, our deacons will retain the old verbal directive to guard the doors, and pray that our heavenly King quiets the heathen. For they are certainly raging loud enough around here just now.