“Good examples are usually extremely useful in the conversion or the correction of men, inspiring them every day to seek after fresh virtues. Even if we had not the warnings of the divine commandments to guide us on the path to heaven, the examples of the saints would suffice.” —From the Vita Prima of St. Wandregesilius

Normandy is an historic region of northwestern France. Comprising lengthy, unbroken coastline, and being fed by the Orne, Eure, and Seine rivers, it has long been a focal point of commerce, agriculture, and exploration. Its history has also been marked by raids and conquest. With such ancient centers as Avranches, Évreux, Rouen, Coutances, Bayeux, and Lisieux, among others, it has seen many changes and upheavals over the long and eventful course of its inhabited history. The time period under consideration in this article covers three major epochs which can be roughly divided according to the major power controlling the region at the time. These are: Roman Gaul (Gallian Lugdunensis), the Frankish era (both Merovingian and Carolingian), and, finally, the Norman era (so named for the Viking Northmen, or Nortmanni, who began raiding as early as the 8th century and seized control during the 9th—10th centuries). It is from this last group that Normandy took the name which it bears to this day.

Among Orthodox Christians in the English speaking world, it is likely that any mention of Normandy immediately evokes associations with the Norman Conquest of 1066 and the ensuing destruction of Orthodox Anglo Saxon England. This is regrettable. Normandy’s history is so much deeper and richer than the tragedy of Hastings and its awful aftermath. Indeed, its history of Orthodox sanctity, both from its pre-Norman and Norman periods, is astonishing both in its sheer quantity and dazzling quality. Some of Western Europe’s greatest saints trod its soil, as the following analysis will hopefully illustrate.

1. Early Figures, Missionaries, and Martyrs

St. Nicasius of Rouen (†c.260)

St. Honorina of Graville (†c.303)

St. Mellonius of Rouen (†c.311)

St. Germanus of Normandy (†c.460–480)

The seeds of holiness were planted firmly in the land now known as Normandy from ancient times. Even before the Edict of Milan or the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea, the Gospel was being lived out and fearlessly proclaimed in this region of northwestern France.

St. Nicasius of Rouen St. Nicasius of Rouen, the Apostle of the Vexin, is one of the earliest saints of this region. The time period in which his life and labors occurred—i.e., the mid-3rd century, long before the reign of Emperor St. Constantine and the legalization in the Roman Empire of the Christian Faith—demonstrates the great antiquity of the Christian presence in the Normandy region.

St. Nicasius of Rouen St. Nicasius of Rouen, the Apostle of the Vexin, is one of the earliest saints of this region. The time period in which his life and labors occurred—i.e., the mid-3rd century, long before the reign of Emperor St. Constantine and the legalization in the Roman Empire of the Christian Faith—demonstrates the great antiquity of the Christian presence in the Normandy region.

Named for an ancient Gaulish tribe, the region of Vexin (only part of which falls within the bounds of modern Normandy proper) consisted of plateaus and river valleys of strategic importance, which made the area a frequently contested one over its history. Its Norman portion is presently bounded by the Epte, Andelle and Seine rivers. This was the area evangelized by St. Nicasius, who traveled among the important villages of the area, such as Conflans, Andrésy, and La Roche-Guyon. Through his preaching and miracles, he converted many in that benighted region to Christ.

A miracle of St. Nicasius that has been recorded occurred during his travels along the Seine, in the village of Vaux. A large snake or dragon-like creature had taken up its abode in a nearby cave from which flowed a spring. Owing to the noxious presence of the beast, the waters were polluted and became a source of sickness and contamination for the villagers. Learning of this, St. Nicasius dispatched his disciple, the priest Quirin, to the dragon’s lair. There, through St. Nicasius’ prayers, the priest bound the serpent with his stole and brought it, vanquished, to St. Nicasius in the presence of the astonished villagers. On that very day, it is recorded, 318 souls received holy baptism—at the very source of the fountain in the erstwhile lair of the serpent, the waters of which had once more become clean and pure. And just as he had cleansed their water from the serpent’s poison, so, too, did St. Nicasius cleanse the spiritual waters of the people of the Vexin from the filth of pagan delusion, giving them to drink instead from the pure waters of Christianity.

Some sources consider it uncertain whether St. Nicasius was bishop of Rotomagus (present day Rouen). His name is not recorded on the lists of bishops of the city. However, there is a long-standing tradition that he was the first bishop of Rouen and was succeeded in that capacity by his disciple St. Mellonius (see below) in 261. At any rate it is quite certain that St. Mellonius was bishop of that important city, though whether he was its first or second bishop may remain subject to debate. It is perhaps all but inevitable that details should be sketchy from this area during this time period. The present author accepts the witness of tradition, and does not consider the absence of direct evidence—especially from so early a time in which persecution was the norm and record-keeping would have been difficult to impossible—as sufficient grounds to dispute, much less reject, the historical memory preserved by the local populace, and therefore accepts the historic attribution to St. Nicasius of the distinction of first bishop of Rouen.

St. Nicasius was martyred with his companions along the banks of the river Epte in Gasny, around the year 260. In statuary he is often depicted as a cepholophore, holding his own severed head in his hands.St. Nicasius’ feast day is observed on October 11.

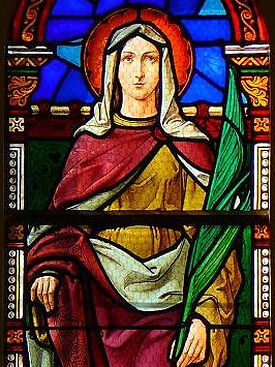

St. Honorina of Graville A second figure of great interest and importance in the early Christian history of the Normandy region is St. Honorina (Honorine) of Graville. However, little is known about the life of this holy virgin-martyr. A Dictionary of Saintly Women by Agnes Dunbar describes her as “a martyr under the Romans in Gaul”1 but does not give any dates for her life. Other sources place her martyrdom around the year 303, during the persecutions under Diocletian.

St. Honorina of Graville A second figure of great interest and importance in the early Christian history of the Normandy region is St. Honorina (Honorine) of Graville. However, little is known about the life of this holy virgin-martyr. A Dictionary of Saintly Women by Agnes Dunbar describes her as “a martyr under the Romans in Gaul”1 but does not give any dates for her life. Other sources place her martyrdom around the year 303, during the persecutions under Diocletian.

Tradition holds that she was from the tribe of the Caletes, who dwelt in the Normandy region in Roman times. (Interestingly, the name of this tribe means “stubborn” or “tough” ones, which designation certainly befits the manly fortitude of this saintly daughter of theirs.) There are conflicting traditions about the location where her martyrdom occurred: The communes of Mélamare and Coulonces have both been claimed to be the site, while other traditions place it somewhere in the Pays d'Auge in which is to be found a number of villages named for St. Honorina. Regardless, her body was subsequently dumped into the Seine and drifted to Graville near Le Havre where local Christians retrieved and entombed it. Her relics came to be venerated and a chapel was built over her tomb. She is both the oldest and the most venerated of Normandy’s virgin-martyrs.

Owing to the imminent threat of invasion by the Normans, in 876 her relics were relocated further inland to a fortress chapel in Conflans-sur-Oise. In the 11th century they were relocated to a priory outside the town walls after the castle had been destroyed in a siege. An annual procession commemorates this event. During the Revolution her relics were hidden for a time by the locals and thereby escaped desecration or destruction. St. Honorina has long been regarded as the town’s heavenly patroness, and it accordingly also bears the name Conflans-Sainte-Honorine. Glorified by numerous miracles, her holy relics remain there to this day.

St. Honorina’s intercessions are known to have liberated many prisoners, and it became traditional for those so benefited to donate their chains as votive offerings. She is also considered a patroness of boatmen, in keeping with Conflans’ role as a port city. Her feast day is February 27th.

St. Mellonius of Rouen The next of the early figures to be discussed in this section was mentioned above in connection with St. Nicasius. This is the Wonderworker St. Mellonius of Rouen. St. Mellonius, disciple of St. Nicasius, was either the first or the second bishop of Rotomagus (Rouen). As is common for the saints of his time and place, only a precious few details of his holy life have come down to us.

St. Mellonius of Rouen The next of the early figures to be discussed in this section was mentioned above in connection with St. Nicasius. This is the Wonderworker St. Mellonius of Rouen. St. Mellonius, disciple of St. Nicasius, was either the first or the second bishop of Rotomagus (Rouen). As is common for the saints of his time and place, only a precious few details of his holy life have come down to us.

Born in Cardiff in Great Britain (modern day Wales), St. Mellonius was originally a pagan before travelling to Rome on a diplomatic mission and being converted by Pope St. Stephen (†257), who thereupon directed him to Rotomagus after ordaining him to the priesthood. Tradition relates that a vision of an angel standing beside the altar during Mass determined this specific direction for his life and apostolic labors. The angel presented St. Mellonius a pastoral staff and, having been duly consecrated to the bishopric by Pope St. Stephen, St. Mellonius set off.

Miracles attended his journey to Rouen. In Auxerre he healed the injured foot of a carpenter by touching it with his staff, and his prayers effected many healings by which great numbers of people were converted. While the saint was preaching in Rouen, a lad who climbed a building to better hear him fell and died, but the holy one restored him to life through his prayers; through this miracle some thousands were converted on the spot, and the lad himself went on the become a priest. Other miracles of the saint included the casting out of a demon from an idol in the presence of many and the purification of a pagan temple which the saint converted into a temple for the worship of the True God. A spring he once used for baptisms, situated at Hericourt, has remained for centuries a site of pilgrimage due to its healing properties: It is popularly known as the “Fountain of Saint Mello.”2

The episcopate of St. Mellonius lasted some forty years. During this long period of pastoral service, he built churches, including temples to the Mother of God and to the Holy Trinity. Unlike his predecessor, St. Nicasius, he did not suffer martyrdom. He died peacefully at Hericourt around the year 311 (some sources say 314). St. Mellonius’ feast day is October 22nd.

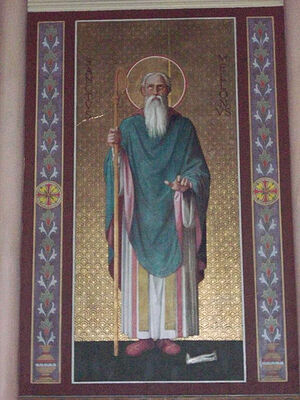

St. Germanus of Normandy St. Germanus of Normandy, it is believed, came originally from the British Isles, probably Ireland or Wales, owing to the designation “Scotus” that was attached to him in the ancient account of his life. He was possibly the son of an Irish prince. A disciple of the great St. Germanus of Auxerre (†448), who baptized him and whose name he took, he was probably converted to the Christian Faith by the latter during one of his two trips to Britain—perhaps the one undertaken in 429 at the behest of Pope Celestine I to combat the Pelagian heresy there, which mission had a successful outcome. He became a priest at age 25.

St. Germanus of Normandy St. Germanus of Normandy, it is believed, came originally from the British Isles, probably Ireland or Wales, owing to the designation “Scotus” that was attached to him in the ancient account of his life. He was possibly the son of an Irish prince. A disciple of the great St. Germanus of Auxerre (†448), who baptized him and whose name he took, he was probably converted to the Christian Faith by the latter during one of his two trips to Britain—perhaps the one undertaken in 429 at the behest of Pope Celestine I to combat the Pelagian heresy there, which mission had a successful outcome. He became a priest at age 25.

According to the traditional account, St. Germanus crossed over the English Channel on a wheel, arriving in Normandy near Flamanville. His motivation may have been, at least in part, a desire to rejoin his godfather. The account of his miraculous passage from Britain to Gaul is as follows: Upon reaching the port at the Channel where he intended to cross, he found neither boat nor fisherman to effect his desired purpose. He therefore prayed, “Lord… if You approve of the plans I have formed for Your glory and the salvation of souls, provide me with the means to cross the oceans. Lead me as You led the children of Israel out of the middle of the Red Sea.”3 At that moment, a chariot wheel descended from the heavens and he made his crossing on it.

Further miracles followed upon his arrival on the coast of Normandy. At the moment of his arrival, a legal case was being adjudicated on the shore. One of the judges, angered by this disruption his miraculous arrival had occasioned, accused the saint of sorcery and uttered other anti-Christian blasphemies. For his audacity, the offending judge was supernaturally struck down on the spot.

Depictions of the saint, who remains much venerated in Normandy, often depict him with a wheel on account of his miraculous crossing of the English Channel. He is also frequently depicted with a dragon, in reference to the account of his killing of a seven-headed beast of this type in the Cotentin Peninsula at Trou Baligan. The account of this latter miracle is as follows: A seven-headed dragon or serpent of colossal size terrorized the area, hoarding and devouring local children. The local populace, in desperation, had taken to periodically offering the beast a child in hopes of placating it, as its constant depredations had left the area in a state of desolation. St. Germanus was besought to free the people from its tyranny. He therefore set out after the dread beast. Along the way, he came across the body of a dead child whom he restored to life through his prayers. The saint then located the cave in which the serpent had its lair. Upon sighting the holy man, the dragon ventured no resistance but rather lowered its head as if in acknowledgement of its guilt. Placing his stole over the monster’s neck, the saint then led it away and sealed it up permanently in a nearby cistern. He worked comparable wonders for the inhabitants of other villages in the Cotentin Peninsula who were similarly terrorized by colossal serpents. As his fame spread, more and more people in the area abandoned paganism and accepted Christian baptism.

St. Germanus passed his time in Normandy in great Apostolic labors. He struggled mightily against both the endemic paganism of the native populace and the heretical beliefs common among the garrisoned soldiers in the area. He labored on behalf of the poor and oppressed as well. Once, upon travelling to Bayeux with some disciples and presenting himself at the city gates, he demanded of the local magistrates that the peasants who had been unable to pay their taxes be released from incarceration; he also requested wine for use in celebrating mass. On their refusal he worked a number of miracles, which finally brought about their compliance.

Later on the saint travelled beyond the bounds of Normandy in Northern Gaul, receiving harsh treatment from the Germanic population of Friesland. He developed a certain lameness in his leg owing to the privations he suffered. The he met with St. Severus (†455), Archbishop of Trier, who had been a companion of St. Germanus of Auxerre on one of his trips to Britain and who may, therefore, have been an old acquaintance of his. To bolster his missionary efforts, St. Severus made him a regional bishop and gave him the following charge: “Found churches of God, where there are none, and, where there are, take care of instructing priests and ministers.”4 This inaugurated a period of missionary travel for the saint that saw him journey through Gaul, Spain, and Italy. In Rome he spent so long in prayer at St. Peter’s Basilica that he fell asleep there; Saints Peter and Paul then appeared to him in a dream wherein they exhorted him to be courageous and “never to cease spreading the true faith.”5

After further labors St. Germanus returned for a time to his native Britain where he commanded much respect and established many churches. However, owing to pressure from the invading Angles and Saxons from the east, combined with similar pressure from the north from the Picts and Scots, the situation was becoming intolerable for the native Britons. St. Germanus was thus compelled to join their exodus to the Continental mainland. During this passage he exorcized a possessed man and calmed a storm at sea. Upon his arrival back in Normandy, in the Cotentin, he restored the sight of a blind girl and baptized her. But he was now nearing the end of his earthly labors. He wished to visit Rouen, but a certain lord named Hubauld opposed him and forbade him entry. The final act of his life was to see him gloriously crowned with martyrdom.

The saint isolated himself outside Rouen with some companions and prayed to God for strength for this last undertaking of his life. The Lord Himself appeared to him in a dream and foretold to him the martyrdom by sword that awaited him, as well as the glorious reward to follow. St. Germanus and his companions spent the entire night in prayer and vigil before heading out to Rouen at dawn. As they travelled up river through the forest and came in sight of Rouen, the soldiers of Hubauld burst in on them, jostling through St. Germanus’ companions who had bunched around him. At this the saint offered up the following final prayer to the God he had served so long and heroically: “Holy, Holy, Holy, invisible and immense, One and Trinity, this is my hour; please remove my soul from this mud hovel; I don't want to stay any longer in this sad existence. I commend to You those I have won for You; grant me only that those who invoke my memory in their prayers may be assured of Your assistance; keep them as, for the honor of Your name, I have kept them.”6 At just that moment, Hubauld himself decapitated the saint with a sword; St. Germanus’ soul was seen leaving his body as a snow-white dove. Hubauld left the saints body exposed to the elements for animals to devour and forbade the local populace to approach it. However, angels transported the holy remains to the other side of the river Bresle. St. Germanus was buried in a small tomb which became a site of pilgrimage as miracles began to be associated with it. A church was built over it, and the village of Saint-Germain-sur-Bresle developed around the site. The saint’s martyrdom took place sometime around the year 460 or 480.

St. Germanus of Normandy is an intercessor for those suffering from fevers and for ill children. His feast is May 2nd.

Thus through the lives and labors of these great early figures, enlighteners, and holy martyrs, we see the deep and ancient roots of the Christian presence in this holy region of northern France. May we always have the benefit of the prayers of these amazing saints!

To be continued…