The heremtic life has historically been very popular in Romania. In all ages the dense forests of the virtually inaccessible Carpathian Mountains abounded with hermits’ cells. There were especially many of them around monasteries, where hermits were much esteemed and always supported. Following the ancient tradition, monastics often left their monasteries and withdrew for some time for intense prayer to deserted places where they had their own secret cells. Most anchorites struggled on Mount Ceahlau. It was a purely monastic, holy Romanian mountain, but other mountains were not inferior to it. The tradition of eremitic life in Romania has never been interrupted: it is still alive, and monks continue to struggle in gorges and precipices. The journalist Bogdan Lupescu has talked about hotbed of hesychasm in the Rarau and Giumalau Mountains. These two mountain ranges are adjacent to each other and are part of the Bukovina Mountains in the north of the Eastern Carpathians. The places here are very beautiful: they have the status of a national park, which is the largest virgin forest of the temperate climatic zone of Europe.

Those who predict their day of death

The hermit Zosima died not so long ago—in October 2008, at the age of 129. A man named Ioan Baron buried him secretly in a high place. Brother Ioan, as he is called here, is one of the few people who personally knew these hesychasts from the mountains (surrounded by a halo of holiness), who saw and heard them and who are allowed to approach their forest hermitages.

The Rarau-Giumalau forest in the Eastern Carpathians. Photo: Stephanel S.

The Rarau-Giumalau forest in the Eastern Carpathians. Photo: Stephanel S.

His testimonies are fantastic. For example, the hermit Zosima had foretold the exact day of his repose a year before he died. He dug himself a grave, and on the day he had foretold he began to wait for his disciple to put him into the grave and cover him up with earth. He told him not to set up a cross over his grave so that no one could know where he rested. His will was that his burial place would not be revealed, so that his disciples from the mountains or pilgrims would not disturb him even after his repose. Schemamonk Zosima was regarded as a man of angelic life.

It was the same with Hermit Nectarie, who fell asleep in the Lord in 2002 aged 108. He had called the same brother Ioan well beforehand to come on the very day on which he had appointed himself to die. His face had been radiant and serene before he lay down in the grave that he had just dug with his own hands.

There were more of them! Many other anchorites from these Bukovina Mountains, strong in spirit, did not want anything earthly to remain after them except for their prayers.

The forests of Rarau-Giumalau are replete with such unknown graves of ascetics who came to know God or even became saints, but not only them—there are also plenty of living hesychasts (and many of them are young) who led austere ascetic lives in caves, underground, even in the terribly cold beginning of the year 2012. So many hermits, and only on one mountain… Who could have imagined this!

Today no one knows where the grave of the hesychast Zosima is, not even those of his few disciples who live hidden in the surrounding forests. It is a grave that you could easily step upon while picking strawberries or mushrooms in some remote ravines. Only one man knows the locations of these graves. He alone knows almost all the places inhabited by the invisible hermits of Mount Rarau. This is Ioan Baron, who for his quiet and devout life (he spent many years in solitude in accordance with all the rules of Christian asceticism) received from the father-confessors of these hermits and even from the Romanian Orthodox Church the blessing to visit many of the schemamonks, help them, and sometimes bring some food to their secret dugouts. A single person! The only link with the world of hermits in these mountains of northern Bukovina. It’s Brother Ioan Baron, whom monks of the surrounding monasteries call the protector of hermits.

Brother Ioan

Fortunately, I found Ioan Baron.

In Campulung Moldovenesc, a frost-and-snow-bound town at the foot of the Rarau Mountains, no one cares that some “eccentric” hesychasts still live there high above their heads, in absolutely wild conditions. I asked many locals if they had heard of something like this.

“Underground?! Who, God forgive, can live there in such cold weather?” was the answer.

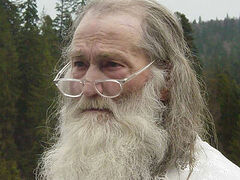

They would also reply, “I don’t know”, “There are no such people.” Thanks to Zosima’s great old age, rumors are still being spread about him as about a venerable old and “paranormal” monk, gray-haired and with a white beard almost reaching to the ground, who has been roaming the surrounding forests for over a century and whom people saw looking like a ghost, because he can become invisible—(“Now he appears, now he disappears among the trees, so you don’t even know if it’s a person or a ghost”). He wanders around and doesn’t want to talk to or see people.

In the Rarau-Giumalau Mountains

In the Rarau-Giumalau Mountains

They also know that Rarau is an ancient center of hesychasm, known since the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, since the time of Sts. Chiril and Sisoe, disciples of St. Daniel the Hesychast (Daniil Sihastrul), that since those times the whole mountain has always been full of hermits. But today? Right now? In the Rarau Mountains? Today, when a European road to a huge mountain ski slope, the largest in the country, is being built over three miles long? When the Rarau Forest has been felled and is visited by many tourists?

Campulung Moldovenesc residents are prosperous people: they have supermarkets like in the capital, they go to good restaurants, attend fitness gyms, saunas and indoor pools, many work abroad only for six months a year. Who cares about what is going on there, in those dark forests? But fortunately, there was a local resident, my good friend Nicolae Iurniuc, a believer and a modest man, a lover of solitude, who for decades walked through the mountains around the town in search of treasures buried underground, collecting stories of old-timers. That’s who he is today—a treasure collector with a metal detector in his hands, walking around the mountains.

This is what happened to him not long ago: He was caught by a terrible storm in the Rarau Mountains. When he realized that he was lost, suddenly someone put a hand on his shoulder. How could another human being have gotten there?

“He appeared suddenly, as if he had just grown out of the ground,” he said—right behind him.

The man beckoned to him to follow him. He led him through the storm to a lonely little house in the forest, through whose windows several lamps could be seen burning. There was a memorial cross in front of the house with a wooden symantron suspended from a huge fir tree, swinging in the wind behind it.

The man put his clothes to dry, seated him at the table and treated him to polenta, vegetable soup, white forest mushrooms and tea.

There were two women in the rooms upstairs who looked like nuns. They went down only once, walked past him, went outside, spent a couple of hours there and then returned. He said to them, “Good evening”, but they didn’t answer. The man from the forest told him that the women almost never talked to anyone. They were hermitesses from Petru Voda Convent, who had vowed not to utter more than seven words a day, and only in the afternoon. He might not ask them anything and say anything to them. Only they did sometimes.

He said that his little house had been set up to accommodate travelers who had lost their way and sometimes to receive hermits, especially those who had just decided to withdraw into peace and quiet and needed some time to dig themselves dugouts, especially if they dug in bad weather and in hard-to-reach places. He just gave them shelter. His name was Ioan Baron.

What did he do? He carried food to hesychasts. He walked dozens of miles both in a blizzard and in rain, with bags on his back (crackers, corn flour, rice, beans, potatoes—everything bought with his pension), which he left in certain places, at the foots of slopes where hermits had secret underground cells, or brought food right to their dugouts if he was allowed to approach them. He made dugouts for them himself (he was an expert in this field) and chopped wood when they had to light a fire in frosty winters. He helped everyone all over the mountain.

He told Nicolae Iurniuc that he could visit his house. He told me about that meeting. And we decided to go together.

Climbing the mountains

With difficulty we drove through the frozen snow, which was as sharp as glass, along the Valea Seaca River that led us into the mountains directly from the center of the town of Campulung Moldovenesc. After five miles the car refused to go any further. Houses were thinning out: it was so nice to look at them from the edge of the forest with their chimneys, from which smoke was coming out in clouds. The last street ended and we began to climb up a steep slope.

An endless forest under a whitish sky, reminiscent of a frozen, fantastic, apocalyptic desert with trees decapitated by the wind, as if after an all-destructive war. I was wearing three sweaters under my thick winter coat, and I had no idea how the hermits could live there in the wilderness at -10 degrees Celsius (and whether they actually existed), since my chin was shaking so much after just an hour of travel, my teeth were chattering and I could hardly say anything.

As we were walking along the mountain crest, my friend Nicolae Iurniuc started peering into the distance, as if not understanding something. I was scared at the thought that we were lost, as it had once happened to my escort. I’m afraid of cold weather! But Iurniuc walked around in a circle for a few minutes, putting his palm to his forehead, and finally realized: Yes, it was there! On the other side of the mountain! We couldn’t see it from where we were, because it was behind fir trees. But it was there—a house of hesychasts.

The one who speaks with saints

He was a robust man of uncertain age in a sheep’s wool hat—this “forest spirit”. He glanced over us from head to toe with his penetrating gaze, smiling with his small eyes. Ioan Baron wore neither a beard nor long hair typical of monks. He always laughed when others told him that they had imagined him to be different, more like a monk.

What difference does it make? He used to wear a beard and long hair when he lived at Pojorata and Sihastria Monasteries, but he did not hesitate to cut them short, like a soldier, because he did not want to be told, “I kiss your hand.” He never wanted to be something or be noticed. He only wanted to help secretly so that no one would know about it.

Pojorata Monastery. Photo: Alexandru Losonchi

Pojorata Monastery. Photo: Alexandru Losonchi

Some monks still call him father today, but he is surprised:

“I have no idea why they call me that!”

Archbishop Pimen himself offered him the ordination and the monastic tonsure, but he is still a layman. And he separated from his wife and two sons (now they are both adults) long ago with their full consent, because they understood his “thirst for solitude.” The thirst that he has had since childhood, since birth, because human cities and villages have never been to his liking, never! He barely overcame himself, having lived among people for so many years until he decided: That’s enough! I have already fulfilled my duty—it’s time to abandon this world forever.”

After that he spent many years alone in a dugout on Mount Giumalau, struggling in the same spirit with other hesychasts in total stillness and isolation. The little house he currently lives in was recently built for him by the local faithful and monastery monks so that he could take better care of hermit schemamonks.

In the Giumalau Mountains, Eastern Carpathians

In the Giumalau Mountains, Eastern Carpathians

A kind man and a local believer named Constantin Arsene helped him most with the construction of the house, supplying him with building materials and giving him two hectares (c. 5 acres) of land for free. Locals really need these hesychasts’ prayers, so they are helping Ioan as a token of gratitude for his tireless gratuitous labors that he performs by taking care of hermits.

The little house on Mount Rarau resembles an archondarik [small monastic guesthouse], with two cells upstairs and Brother Ioan downstairs. He doesn’t need any comfort in this house. He feels like just an administrator and out of his elements here, and lives here only as obedience. He says that if it were up to him, he would continue to stay in his “hole” (cell) on top of Giumalau, where there was “such silence: I did not see a single human face from October to January.”

Brother Ioan’s house, converted into a “mansion” by zealous good people. Photo: Doxologia.ro

Brother Ioan’s house, converted into a “mansion” by zealous good people. Photo: Doxologia.ro

It was so quiet all around! Such peace!.. He shared it with us, inviting us to the table with a smile and firmly making it clear that we should not hurry to “give him an account” of why we had come. Even though he knew that we would be asking him about very subtle things for a newspaper, but that’s not what interested him right now. He wanted something else: for us to indulge together in the blissful feeling that we had met, that we were his guests and he was our host. We would have time to talk later. In the meantime, we had a bowl of polenta—golden, steaming and stuffed with layers of sheep’s cheese. We said a short prayer before the meal. Coal was crackling in the stove. A blizzard was raging outside and knocking on the windows from all sides…

A “ghost of the mountains”

I don’t know if he liked us or he behaved like this with all travelers wandering around the mountains and curiously asking him about what the hermit’s life is. In the end he began to tell us everything frankly.

“Yes, I knew Schemamonk Zosima. On the day he had already asked me to come I found him lying by the grave and waiting. He had just passed away. He was lying quiet and soft and seemed to be immersed in sleep. When I took him into my arms to put him into the grave, I saw that his body was quite light and fragrant.

“He was one of the long-living hermits, was filled with the grace of God, and had a reputation in Orthodoxy as a great prophet and a visionary. He was close to Father Daniil (Sandu Tudor) from the Rugul Aprins (‘Burning Bush’) movement. Together they were inseparable at Rarau Monastery, and Zosima was even older than Daniil. He moved away to the mountains, persecuted by the Communists by the decree of 1959, and led an ascetic life in the rocks. A rumor spread that he was dead. After some time, the secret police stopped searching for him, and he remained in the ‘desert’ forever.

“I saw him for the first time in 2000. It’s true what people say—it was as if he could become invisible. You knew he was somewhere close by, you felt his spirit, but you didn’t see him. So initially he would be invisible for me. Maybe he had gotten to know me better secretly, but he began to appear more often.

Mestecanis Pass in the Eastern Carpathians

Mestecanis Pass in the Eastern Carpathians

“He had long curly hair that fell over his shoulders like an umbrella. He looked like a ‘ghost of the mountains’, with needles and leaves in his hair, with a beard that reached to his waist. He walked leaning on two sticks, did not talk to people, and people rarely heard his voice. With great difficulty he allowed me to come to him, even though I had a blessing from monasteries and spiritual fathers. He was always barefoot, hardly needed any food, and the food I would bring him was usually left untouched.

“I began to talk to him. Several times he even invited me to his cell: it was very far away. I think that with his keen eyesight he had managed to find the most inaccessible place on the whole mountain. In winter it could only be reached by helicopter. However, I am not really allowed to say what I have told you.

“I spent many nights with him, because he only spoke at night. So many spiritual words, so many edifying words! But I wouldn’t like to talk about that. These words are so powerful that it is very easy to misinterpret them… Who am I, an ignoramus, to allow myself to utter his words?

“I only performed obediences: I would be sent or called somewhere. I will only tell you that he predicted events that are very significant for Romania and the whole world. How did he know all this, if he didn’t leave this mountain for over 100 years?

“He left behind a few disciples here. I know two of them: a hesychast called Calinic and another one… But I won’t be able to take you to their dugouts this winter…”

Cross on top of Giumalau Mountain

Cross on top of Giumalau Mountain

There is a white, high stone cross on the highest peak of Giumalau. In a rectangular niche cut in this cross you can see several candles, a bottle of oil, a box of matches (always dry) and an icon lamp. Written on a white stone nearby are the words, “Do not take oil from the icon lamp, or matches. Holy hermits meet here and pray for us.” This is indeed their meeting place. Only a few days a year hesychasts ascend to this cross from their hiding places and pray together. They stand there side by side, under the cross. Maybe they sing. Sometimes they can be seen with binoculars through the foggy haze from Mestecanis, another peak.