An eyewitness’ notes

From the author: Dear editors of Pravoslavie.ru!

In the spring of 2021 I was vouchsafed to visit the hermits of the mountains of the Caucasus, after which I wrote a small essay entitled, “On the Ascetics of the Caucasus of Our Time.” I humbly ask you to publish it on your website on the day of the Venerable Fathers who have shone forth in ascetic labors, who are commemorated on March 5. I believe this article will serve to increase the zeal of monastics and the faithful in the Christian ascetic struggle.

If possible, please publish it anonymously, and sign it, “Eyewitness Evidence.” I have deliberately abbreviated the names of the ascetics to avoid the temptations that are caused by modern PR and which have a negative impact on monastics.

Schemanun Maria and Hieromonk Achillas

Schemanun Maria and Hieromonk Achillas

Of whom the world was not worthy: they wandered in deserts, and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth (Heb. 11:38). These words, written by the Apostle Paul in the first century of Christianity, like no others reflect the ascetic struggls of hermit monks living in the mountains of Abkhazia in the twenty-first century.

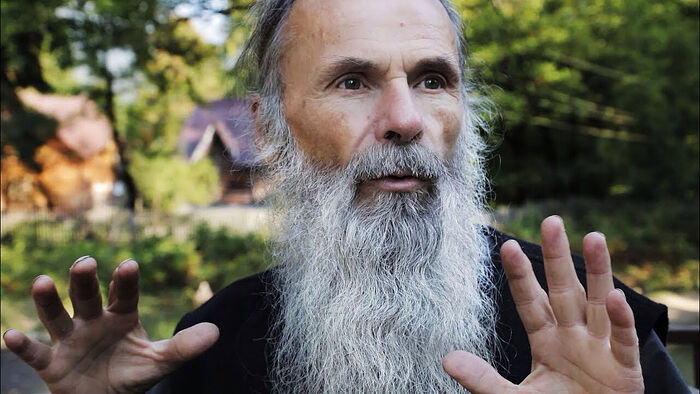

Monk Isaac (Uchkin)

It is known that some pious monks, seeking solitude, with the blessing of their father-confessors, leave their monasteries and go to the Caucasian mountains. So did Monk Isaac1. Having been tonsured in the Lavra of St. Sergius, in the 1990s with the blessing of Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov; 1919–2017), he retired to the Abkhazian mountains. How he lived and struggled there is a great mystery.

In his youth Fr. Isaac was an avant-garde artist and in solitude continued to paint icons. His icons now adorn the church in the Abkhazian village of Pskhu in the Sukhumi district. Batiushka also had literary talent; he wrote short stories and philosophical essays.

In 2018 he went missing in the mountains, and all the brethren’s searches for him were in vain. A year later (in the spring of 2019), the Lavra’s Spiritual Council raised the question of whether to exclude Fr. Isaac from the brethren or not. At the same time, a letter came from Hierodeacon D. (who also struggles in Abkhazia):

“Father Isaac was found on the other (the Resheva River) side of the Bzyb River, near a tiny rivulet, with rocks and caves next to it. There is a hole in his skull. The place is steep; he must have fallen headlong on the stones; or an avalanche might have killed him. He probably had a secret cell there because he was wearing a backpack (containing nuts and tea) and had a large plastic container with him. Apparently, he had lost his balance and fallen off. Only his skeleton remained by the spring, but animals did not touch it (only his skull was damaged). It is also supposed that he was climbing up his makeshift ladder into his cell, but it had rotted and he fell off (we used to walk there; the mountain is dotted with caves. We climbed ladders made of ropes and sticks back in the mid-1980s).”

After Brother Isaac’s body was found he was buried as a monk, dressed in all his monastic vestments.

A hermit on the way to his cell on top of mountains

A hermit on the way to his cell on top of mountains

The hermit fathers composed the following quatrain in honor of the reposed Monk Isaac:

I don’t even need a wooden coffin—

A hermit’s coffin is in his soul.

You are always ready for death, everywhere,

It’s good for a hermit to die on the path.

St. Sergius always takes care of his brethren regardless of where they labor, and after their deaths he keeps them in his Heavenly abode. Now the Lavra brethren pray for the repose of Monk Isaac, commemorating him at Liturgies and memorial services.

Hieroschemamonk N. with the brethren

Several times a year, Hieroschemamonk N. walks down from the Sukhumi mountains to hear his spiritual children’s confessions and acquire what is necessary for his skete.

Hieroschemamonk N. is about seventy. Previously he struggled at a large Ukrainian monastery and performed official obediences there. Longing for the solitary life, he retired to the Caucasian mountains, eventually set up a skete and gathered together a small number of brethren. It takes a long time to get to his Holy Trinity Skete—about an eight-hour walk through impassable forests, mountains and ivy thickets. This place is called Amtkel—after the name of a lake. At the beginning of 2021 the skete church burned down, and in the summer the brethren decided to build a new one.

In order to purchase a minimum of provisions, for some time the hermits descend from the mountains and stop at a house in a suburb of Sukhumi. The nuns who live nearby try to serve the hermits in any way they can, but the brethren refuse out of modesty and their inherent asceticism.

The day Fr. N. came down to us from the mountains, Monk F. came down too. Formerly a monk of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, he moved to the mountains with the blessing of his spiritual father, Archimandrite Kirill, in 2000. When we were once walking along a mountain stream, we asked him why he had chosen the eremitic way of life. The ascetic replied, “It is impossible to love God ninety-eight percent—He must be loved one hundred percent.” This monk is very devout and inwardly concentrated. He doesn’t speak much. In all his spiritual appearance one can see the awe and respect with which he treats clergy—something that is lost in modern society.

Sukhumi residents try in every possible way to serve the brethren who come down from the mountains for a short time. It is felt that people need their prayers and appreciate their labors.

There is a medieval church of St. John Chrysostom on a small hill near the village of Comana to the north of Sukhumi. The road to Comana lies through the villages of Yashtukha and Shroma, which were badly damaged in the war of 1992–1993. For the last two centuries the church of Comana has been one of the greatest pilgrimage centers. This ancient church was built in the eleventh century. In the late nineteenth century it was restored with new additions: two side-chapels from the north and south, and a three-storied bell tower covered by a high bell tent from the west. During the construction of the bell tower a stone sarcophagus with St. John Chrysostom’s relics was discovered. It was in this spot that he died on September 14, 404, when he was on his way to exile in Pitiunt, having been banished from Constantinople by decree of Emperor Arcadius. Both the church and the monastery bear the name of the great holy hierarch.

The church is beautifully decorated, with small copies of the holy hierarch’s tomb handed out to pilgrims as a keepsake. In addition to the saint’s tomb and the lectern icon of St. John Chrysostom with a particle of his relics, the church treasures include an icon of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, an Iveron Icon of the Mother of God (the Patroness of this land), a “Deliveress” Icon of the Theotokos (especially venerated in Abkhazia), an icon of St. Basiliscus, and an effigy of the head of St. John the Baptist on a platter. The site of the third discovery of the head of St. John the Forerunner is in the mountains not far from Comana. A path leads there, a staircase was built there, and a pilgrimage route marked.

In the Soviet era the Church of St. John Chrysostom was very dilapidated. But in 1975 it was restored at the personal expense of a local resident, Yuri (George) Dmitrievich Anua.2 During the Abkhaz-Georgian conflict the shroud with an image of St. John Chrysostom, embroidered by nuns back in Byzantine times, disappeared, and so far it has not been found. The sarcophagus was desecrated. But a particle of St. John Chrysostom’s relics was preserved thanks to the efforts of Zoe Anua, now a parishioner of the church.

Until 1917 there was a monastery (later a convent) of St. John Chrysostom in Comana. It was revived in 2001. In the 2000s, some monks and novices labored here, preparing for an ascetic life in the wilderness.

St. Michael’s Cemetery

Many ascetics of both sexes are buried in the cemetery around St. Michael’s Church a mile away from Sukhumi. A white chapel with a blue dome rises up close to the entrance. This chapel was built over the grave of Hieroschemamonk Paisiy (Uvarov; 1952–2002). His brief biography with an epitaph and spiritual instruction can be read on black marble plagues:

“This chapel was erected on the burial site of the blessed Hieroschemamonk Paisiy, who for the last twenty years of his life labored in the Caucasian mountains. He was tonsured at the Holy Trinity-Sergius Lavra, and graduated from the Moscow Theological Academy and Seminary. He is known as a zealous ascetic and an experienced pastor, who by his personal example brought many to Christ.

“Give rest, O Lord, to the soul of Thy departed servant Hieroschemamonk Paisiy, and through his holy prayers have mercy on us.”

“Hieroschemamonk Paisius

(secular name: Pyotr Ivanovich Uvarov),

born December 13, 1952,

died November 8, 2002.

May the Lord give you in Heavenly abodes

Eternal joy and peace.

Pray for us, O Blessed Paisius,

And vouchsafe us a meeting with you in Heaven.”

“I ask of you all one thing: live in peace. Peace and love are the most important things. If you have this among you, nothing else will be needed and you will always have joy in your souls. You will not be saved by anything that is outside you, but only by what you attain inside yourselves, in your souls and hearts—the peaceful stillness of love—so you must never give anyone an unpleasant look. Look directly with readiness to every good answer and good deed with heartfelt sincerity. This is my last appeal to you. Love one another. Monastic life is hard, but it is also the easiest life…”

The Venerable Seraphim (Romantsov; 1885–1976), Abbot of Glinsk Monastery, moved after Glinsk was closed in 1961 to Abkhazia, where he first lived in the city of Ochamchira. Then with a parishioner in the village of Ilori, later in Sukhumi, and finally made his residence at Dranda Monastery. He, too, was buried in this cemetery, and his holy relics rested here until their uncovering. His former grave with a wooden cross is maintained and revered by locals.

Hieromonk S. and Hierodeacon O.

Hieromonk S. lives in an abandoned settlement not far from the village of Tsebelda. He is engaged in beekeeping and breeding of animals, and carves tonsure and paraman crosses for monks. It is from his little hermitage that the mountain road to the hermits in Amtkel—where we went—begins. It takes two or three hours to climb up a steep rocky slope. Then for about four hours you proceed along a road made by hunters and lumberjacks. And next you walk for about an hour through impassable thickets of ivy and beautiful but poisonous rhododendrons.

Only two springs flow from the mountain peaks throughout this long journey.

On the way, from one mountain you can see the village of Georgievka, where the ascetics Schemanun Elena and Nun Nina3 lived. After some distance from another mountain a beautiful view of the surrounding mountains opens up, and, following the established tradition, the hermits, passing this place, sing the Paschal troparion.

From the mountain a sharp descent through thickets of fragrant purple and yellow rhododendrons takes about two hours. Hierodeacon O., who was tonsured at the Pochaev Lavra, has been living here in seclusion for over seven years. There are two cells: one is where batiushka lives, the other is empty. The refectory is outside, with a large tree leaning over it that could fall at any moment and destroy the refectory with the empty cell. Fr. O. says that “this tree has bent down for the memory of death.” There are beehives next to the cell. They were brought here from Fr. F.’s cell—it is closer from here to take honey to the city in exchange for the necessary food and things. There is no water nearby, and the recluse has to climb uphill to get water to fill large canisters.

Early in the morning we went down from the mountain through a forest, crossed a river and climbed up to the mountain again. This part of the journey took three to four hours. It was impossible to go along the other path, since an avalanche of rocks had recently fallen from the mountains and it was littered with rocks. After that, for about two more hours we walked along the path to Monk F.’s cell. There we also had a steep descent, but not as long as that to Fr. O.’s cell.

Before to Monk F., Schemamonk Cassian (Yermakov; 1927–2012)4 had struggled in the same cell for fifty-four years. Apparently, before Fr. Cassian someone had lived in this place too, since old clay vessels were found when the foundation was being strengthened. Next to the cell there are woodsheds, along with a refectory converted from a shed for bees. Close by is a cell-church with two wooden plank beds. The church is dedicated to the Protecting Veil of the Mother of God. Before the patronal Feast and after Pascha Monk F. walks down from the mountains to purchase the necessary supplies for the winter and summer. In the middle of the complex stands a cross, in front of which litias are served for the repose of “those who labored in this desert place.”

The hermits’ diet mainly consists of herbs that grow near the cell (burdock and nettle) and vegetables. Some beans and potatoes grow in the garden. To break the fast for the feasts with fish you need to walk down to the river, but the descent is so difficult that the enterprise is not worth the “consolation”. Once the monks planted peach trees, but as soon as they began to bear fruit, a bear came (there are many of them here), broke up the trees and ate all the fruit.

Not far from Fr. F.’s cell, with the blessing of Fr. Cassian, a new cell was built. Initially Fr. F. lived in it. Now it is empty.

Then you climb uphill. You need to walk along a flat road amid the forest thickets, and only then can you go down to Monk P.’s cell. He and Fr. F. call each other neighbors, although the journey takes about an hour and a half. Monk P. settled in the mountains about five years ago. His monastic path began in the Pskov Caves Monastery (he was a laborer there), and he was tonsured in the mountains. He eats only bread and water and looks very young: he doesn’t even look thirty years old.

On the feasts of St. Nicholas and St. John the Evangelist, the Liturgies were celebrated in the Church of the Protecting Veil of the Theotokos, to which all the aforementioned brethren came. On the eve of both feasts Vigils were held, and the Liturgies were preceded by confessions. All the recluses took Communion. At the Liturgy an unusual petition sounded at the litany: “For this desert, every city and country...” On the namesday of Patriarch Kirill (May 24), after a meager meal, many years was proclaimed for “Our Great Lord and Father Kirill…”

The monastic prayer rule of the desert-dwellers does not differ from that in Russian monasteries: three canons, two akathists, a kathisma, the Gospel and the Epistles. The brethren did not answer our question about the number of Jesus Prayers they recite daily—obviously, everyone has their own blessing.

According to the hermits, the hardest time for them is winter, since the enemy tempts the ascetics in snow-covered cells particularly cruelly with thoughts.

Eagle-owls, rocks and bears

One night, an eagle-owl and an owl flew up to Fr. F.’s cell and made their characteristic sounds all night long. The former shrieked: “Uh-huh, uh-huh, uh-huh...”, to which the latter echoed, as if laughing: “Ha-ha-ha...”

Once in autumn a large rock fell off the mountain and with a thunderous noise flew right towards Fr. F.’s cell. The monk was then in the cell. It seemed to him that an earthquake or a volcanic eruption had begun. It seemed that death was inevitable. However, right in front of the cell a tree stopped the rock. If it had not been for that, the rock would have smashed all the buildings and crushed the ascetic who was standing at his prayer rule.

If you walk through the impenetrable forests from Fr. F.’s cell for at least six hours, you can arrive at the place where nuns live. One of them took care of the hermitess Schemanun Maria in the final years of her life. After Mother Maria’s repose, her sister joined her, and both began to live together in the hermitage.

According to the mothers, once Schemanun Maria was walking along a narrow path with a large pack on her shoulders. There was a bear in her way. Below was a gorge, and above was a mountain. The nun affectionately turned to the animal: “Mishka [a diminutive form of the word “medved’”, meaning a “bear”, in Russian.—Trans.], will you let me through?” After these words the bear stood up on its hind legs over the gorge, leaning its front paws on a rock—and the nun passed under it.

The way back

On our way back we walked through mountain landslides. On the road at the spring we met a bear that was frightened of us and ran away, leaving a trail of broken trees behind it.

The way back took us about nine hours.