No matter how many difficulties there may be in life, there is so much more left

in which one can draw the meaning of life, and strength, and even the joy of life.

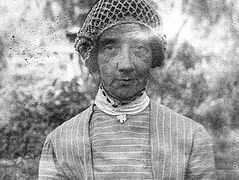

Natalia Frederiks

Baroness Natalia Frederiks was born on July 8, 1864, at her ancestral estate of Znamenovka in the Bakhmut district of the Ekaterinoslav Governorate (now Donetsk Oblast) on the feast of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. She was the daughter of a hereditary nobleman, Imperial Army Colonel Modest Alexandrovich Frederiks,1 and Countess Elizaveta Alexandrovna, nee Geiden. Natalia had one brother, Baron Nikolai Modestovich Frederiks, a lieutenant in the Egersky Guards Regiment.

The Frederiks baronial family was known in Russia since the eighteenth century. The ancestor of Baron Modest Alexandrovich, Ivan Yurievich Frederiks, was a court banker of Empress Catherine II, who, for his honest service, was granted the title of baron on August 5, 1773. Natalia's grandmother, Countess Anna Alexandrovna Geiden, in 1898 helped build a church dedicated to the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the village of Petrovka-2, located near the Znamenovka estate. She also donated fifty desyatins (130 acres) of land for the maintenance of the church. Possibly the village of Znamenovka itself belonged to her, where later Natalia's parents built a brick factory.

Baron Modest Frederiks' family lived in St. Petersburg, where Natalia graduated from the Mariinsky (Foundry) Gymnasium. It was the first mixed-social-status female educational institution in the country. Girls studied for seven years, during which they received comprehensive knowledge. Unlike other institutes, the students lived at home, within their families.

After the death of her parents, Natalia Modestovna inherited the village of Znamenovka and 3000 desyatins of land. Later, she also acquired a house-estate in Yalta. Natalia was wealthy but lived very modestly, dedicating much of her time to philanthropy. In 1895, she became a member of the St. Petersburg Cross Charitable Society and was on its board of directors. The society was established by representatives of the Petersburg nobility to aid all those in need, regardless of rank, gender, age, or creed. It provided the destitute with clothing, food, shelter, medicine, and, in extreme cases, financial support. It placed the elderly in shelters and almshouses and allocated funds for the education of children.

In her estate, Natalia Modestovna built a hospital and an elementary school for peasant children, and organized festivities for peasants. She was reserved by nature and loved solitude. Her brother, Nikolai Modestovich, died in 1892 at the age of thirty, leaving a widow with two children. Natalia was very close to her sister-in-law, Elena Iliodorovna Frederiks (born Shidlovskaya), and helped her raise her nephews, Dmitry and Vladimir. Natalia herself never married. She usually spent winters in St. Petersburg and summers either in Znamenovka or in Crimea. Living on her estate, she read much, painted watercolor sketches, planted flowers and trees, and managed the estate. This continued for many years until her tranquil life was disrupted by the outbreak of the First World War.

At the onset of the war, Natalia Frederiks enrolled in nursing courses. For a while, she worked as a surgical nurse at the Tsarskoye Selo Palace Hospital, then went to the front as a Sister of Mercy in the sanitary-nutritional train named after Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna as part of the 4th Army. For her devoted work, on November 9, 1915, Natalia was awarded the Silver Medal “For Diligence” on a distinguished ribbon. Having witnessed all the horrors of war, she turned to God in repentance and secretly took monastic vows.2

After the revolution, Natalia Modestovna remained in Russia while her other relatives emigrated. Apparently, she lived on her estate in Znamenovka until it was expropriated by the new regime. She herself stated that the revolution “freed her from property ownership.” Natalia Modestovna returned to Petrograd and in early 1919 began working as a librarian at the Pedagogical Institute for Preschool Education, where she worked until July 1919. She led a modest and secluded life, attending church services.

She was first arrested on July 11, 1919, as a former baroness, and by a resolution of the Petrograd Cheka on November 7, 1919, she was “sent with her case to the All-Russian Cheka 24/U11-19 for imprisonment in the Moscow camp.” After spending six months in a camp near Moscow, she was released in February 1920. From the fall of 1920 until the end of 1922, she worked again as a librarian at the same institute but was dismissed due to staff reduction. Left without any means of subsistence, the former wealthy landowner earned a living by giving private lessons to children.

Until February 1924, Natalia Modestovna was a member of the parish council of the St. Sergius Cathedral on Liteyny Prospekt in Petrograd, where she sold prosphora. She was also a member of the Orthodox Charitable Brotherhood of the All-Merciful Savior (Spassky Brotherhood). The Spassky Brotherhood organized food and clothing aid for those held in the prison infirmary on Pereyaslavskaya Street, as well as a free canteen where sixty to a hundred people were fed daily. In the spring of 1922, arrests of the Brotherhood’s members began across the country.

On February 3, 1924, Natalia Modestovna was arrested “for active church activity in the parish.” She was held in pretrial detention in the Special Purpose Prison (DPZ) “of the first category.”

During interrogations, in order to avoid implicating relatives and friends, the former baroness stated:

“I have no close relatives... I have no acquaintances with whom I constantly associate. I am very occupied with work at the St. Sergius Cathedral, and therefore, I do not go anywhere, and no one comes to see me.”

Regarding her attitude toward the authorities:

“I am indifferent to the Soviet government. However, I am thankful for the revolution as it freed me from property and secular obligations, which would have been a challenge for me to renounce.”

Regarding her political beliefs:

“I have none because I am a religious person, and politics do not exist for me.”

During one interrogation, she testified about herself:

“Until 1913, I had little connection with the Church as I was not particularly religious. But since 1913, I increasingly strengthened my spiritual faith... Now I have fully devoted myself to the Church.”

From February 3, 1924, until September 26, when the final sentence was issued, Natalia Modestovna was in the Preliminary Detention House on Shpalernaya Street in Petrograd. The second arrest ended with her being sent to Solovki: On September 26, 1924, by a Special Council at the OGPU Collegium, Natalia Modestovna Frederiks was sentenced to two years in the SLON (“Solovki Camp of Special Direction”) concentration camp, where she arrived on October 25, 1924.

The main types of women's work in Solovki included laundry work, rope-making, peat extraction, and work at a brick factory located two kilometers from the monastery. “Brick-making” (molding and carrying clay) was considered the most challenging. The sixty-year-old baroness struggled immensely with the “brick-making”; she was involved in molding clay—unbearable work for her age. The criminal inmates mocked her: “Hey, baroness! Lady! This is not like dragging the Tsarina’s train! Work like us!”3 They constantly ridiculed her, attempting to humiliate her in every possible way.

The internal life of the women's barracks was a hell, where an aristocrat found herself among prostitutes, criminals, smugglers, and brothel madames. Among the inmates were noblewomen who kept to themselves, conversing in French. Natalia did not get close to any of them.

Every evening, after returning from hard work in the barracks, Natalia Modestovna silently ate a bowl of codfish stew, then knelt before a small icon and prayed for a long time. After carefully tidying her clothes and shoes, she lay down to sleep on a neatly arranged bunk. It's known that a person’s true essence manifests itself during tough times. The saintly ascetic Natalia bore all the hardships of camp life with humility, considering her fate as a cross sent to her that must be carried without complaint or tears in an atmosphere of foul language, fights, and mockery. She treated both criminals and women from her own circle with equal friendliness, seeing the divine image in each person. She carried herself with a sense of dignity but never lectured or displayed superiority over others. An aristocrat in the truest sense, she remained noble, pure, and possessed high moral qualities.

Natalia Modestovna became greatly weakened while working in the brick factory, so she was transferred to the role of supervisor for the children of the camp leaders. As the sorrowful days on Solovki passed by, attacks on the Baroness became rarer day by day. Gradually, the attitude of the other inmates towards Baroness Frederiks changed significantly. Seeing her self-control, honest work, and kindness, they began to respect her and sought her advice. Due to her cleanliness, she was unanimously elected to the honorary position of barrack cleaner, which included washing the floors and tending the stove. Her personal record noted: “Handles assigned duties well and conscientiously, behavior is excellent, disciplined”; the overall review mentioned: “Exemplary behavior, good work”; and in the disciplinary action section: “No incidents”.

The spiritual influence of Baroness Frederiks on her fellow inmates grew stronger. With her love, inner culture, and sense of duty, she transformed human souls, leading some to faith. During Holy Week in 1925, under Natalia Modestovna's influence, five female prisoners from her barracks, including herself, confessed and received Communion from a camp priest, whom brave inmates secretly brought into the Solovki theater building and hid in the costume room. The priest administered the Holy Gifts in a secluded corner.

Chaos erupted on the Solovki Islands a year later when a typhus epidemic broke out, and a typhus ward was set up on the remote Anzer Island. Medical staff were scarce, as no one wanted to tend to typhus patients, knowing it was akin to a death sentence. The camp administration turned to the prisoners for help. Baroness Frederiks was the first to volunteer to care for the sick prisoners. Several of her fellow inmates followed suit. Because of her experience as a Sister of Mercy, she was appointed as the senior nurse in the quarantine ward. She cared for the typhus patients lying on the floor, clearing away dirty sawdust and filth from beneath them. Solovki prisoner Anna Sergeevna Arsenyeva recalled:

“The winter of 1925/26 brought many victims. In December, the first reports of those affected by abdominal typhus emerged. The elderly Baroness F. and I requested permission to care for the sick, and upon receiving it, we went to the typhus isolation ward. The Baroness and I didn't have a single free moment. At night, one of us, fully dressed, would sleep while the other kept watch. We had to work tirelessly. Lice against which we were utterly powerless crawled over our hands and the walls. Only one woman was assigned to help us; she washed the floors and dishes. Apart from her, no one assisted us in this difficult and dangerous task. Every three hours, we had to rinse the patients’ throats with a glycerin solution to prevent ulcers. Some resisted, not comprehending in their delirium why they needed it. They would push us away with cries and fists, refusing our aid... Bishop Agapit, our first patient, recovered and was transferred back to his cell in stable condition. He often visited us, and when the camp was asleep, he sneaked into the infirmary to comfort the dying and absolve them of their sins."

When signs of illness appeared in Natalia Modestovna, the head of the medical unit urged her to move to a separate room, but she declined, saying, "Why bother? You know that at my age, one doesn't recover from typhus. The Lord is calling me to Himself, but for two or three more days, I can still serve Him."

Her service continued for two more days; on March 30, Natalia Modestovna died while attending to the sick. Before her death, Bishop Agapit administered to her the Holy Mysteries of Christ.

Baroness Natalia, having died from typhus, was buried in a common grave at the former monastery cemetery, located not far from the women's barracks. It was destroyed in the 1930s, and a military hospital was built in its place.

On November 14, 1981, by the Hierarchical Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR), Nun Natalia of Solovki was glorified among the host of new martyrs and confessors of the Russian Church. Her memory is celebrated on March 30—the day of her repose. In 1991, Natalia Modestovna Frederiks was officially rehabilitated by the Prosecutor's Office of St. Petersburg. On May 14, 2019, a solemn opening ceremony was held for a memorial plaque placed on the wall of the St. Nicholas Church in the village of Petrovka-2, Alexandrovsky District—the parish church for the village of Znamenovka, Natalia Modestovna Frederiks' birthplace.

St. Natalia of Solovki, pray to God for us!