This article talks about the life of Nikolai Ivanovich Egorov, the future Archimandrite Dmitry, who escaped the Solovki camps and entered Valaam Monastery as a novice in the 1930s. Later, he founded several sketes in America, where he reposed in 1992.

The Kazan Icon of the Mother of God Skete in Santa Rosa

The Kazan Icon of the Mother of God Skete in Santa Rosa

According to the recollections of his contemporaries, he lived a life that was beyond modest, meek, and humble; he was considered a fool for Christ during his lifetime—not everyone could endure the rigor of his life and the height of his spiritual feats.

For example, riding on public transportation, the Elder could suddenly raise his hands to Heaven and start praying loudly, or get down on his knees on the street. Fr. Dimitry also brought a Ukrainian refugee to the skete who was suffering from schizophrenia and demonic possession. During periods of remission, he was calm and prayed and did obedience along with everyone else, but during attacks, he would grab a knife or an axe and run after Fr. Dimitry. After being treated in a clinic, Fr. Dimitry would invariably let the unfortunate man back in, somehow managing to pacify him. One novice who left the skete, an American, recalls how the possessed man rushed at him with a machete when he was about to ring the bells.

Another example comes from a carpenter from San Francisco who would visit the skete every week. He decided to take the construction of the skete into his own hands and himself decided what to do and where, without asking the abbot, Fr. Dimitry. The Elder had great love for him and never forbade him from doing what he wanted.

Every year during Great Lent, a well-to-do lady would come to the skete and bring all sorts of fasting delicacies she had made. And Fr. Dimitry, a strict faster and recluse, would meet her and eat with her. To the novice’s bewilderment, he said that this lady brought food prepared with such diligence as an offering to God, not to Fr. Dimitry personally, and if he refused, she would consider it as God rejecting her. The Elder didn’t want to offend her. One of the Elder’s spiritual daughters said that if “this kind woman saw and knew how strictly Fr. Dimitry fasts, she probably wouldn’t have done this year after year,” but no one knew except those closest to him.

There were many among the clergy who were envious of Fr. Dimitry, according to the recollections of his contemporaries; he was the victim of much slander, which he endured with love and patience. Visitors would often come to the picturesque place where the St. Eugene Skete was located to have picnics. They got in the habit of putting their empty wine bottles in one place, until there was a whole mound of them. Then someone started a rumor that the good hieromonk had problems with alcohol. Another rumor accused him of avarice. People often donated to Fr. Dimitry for the monastery, but since it belonged to the diocese, he was worried this money might be “appropriated” for diocesan needs. Therefore, Fr. Dimitry would deposit the donations in the bank in his name and would withdraw funds from time to time for their intended purpose. Evil tongues spread rumors that this man of God was taking Church money for his own needs. But his parishioners insist that “nothing could be further from the truth,” for he was “so non-acquisitive and thrifty that he not only fixed his own clothes, but also washed them in the same water that he bathed in.”

Since his time at Valaam, having preserved his love of the desert life, he never refused trips to serve in distant parishes, which young priests didn’t want to do because of the low pay. “I have to serve people!” he would say. People recall that he humbly endured the harshness of his archpastor, and Archbishop John (Shahovskoy) would say of him: “This is my only obedient priest!”

Things often happen with elders that are beyond human understanding. There’s a story of how Fr. Dimitry “healed” a large Douglas fir that was already almost felled. One day, a neighbor of the skete, who from time to time was allowed to cut down a tree for his own needs, was refused. The neighbor decided to do it secretly and started cutting down a lone tree by the side of the road with a chainsaw. Fr. Dimitry suddenly appeared and stopped him. Caught in the act, the neighbor embarrassingly loaded his equipment into a truck and drove off. But three weeks later he saw that the tree had completely “healed,” which, in his opinion (and he knew his business well), could not have happened, because he had already cut halfway through it. The tree would have fallen due to its weight and the extent of the cut. But “the three was healed on its own; there were no signs of the cut or that it had been chopped—no trace at all! It was impossible. A miracle! I think the priest healed the tree,” the neighbor said. And he wasn’t a religious man.

Those who knew the Elder from his parish ministry believe that the way Fr. Dimitry avoided disputes and quarrels was “not a weakness,” as some thought, but a “strength.” He followed the hesychastic spiritual tradition, practicing silence and the Jesus Prayer. “Although he sincerely preferred a skete or a monastery to a parish, he obediently and humbly bore his cross, teaching others by his example.”1 According to one of his novices, the Elder behaved as though he were a stranger on earth and an “eternal pilgrim,” ever striving “for the Heavenly Jerusalem.” His favorite expression for the spiritual life and for achieving anything was: “Little by little, step by step.”

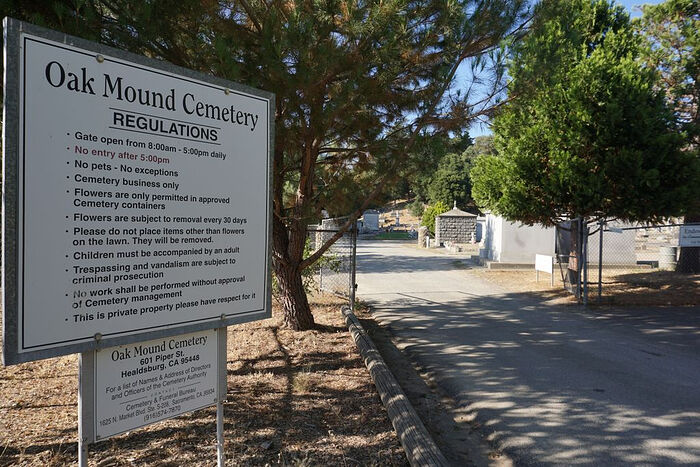

Oak Mound Cemetery in Healdsburg, where Archimandrite Dimitry is buried

Oak Mound Cemetery in Healdsburg, where Archimandrite Dimitry is buried

Archimandrite Dimitry managed to raise a whole galaxy of monks in the U.S. He is remembered as a spiritual father by such well-known American Church figures as Metropolitan Jonah (Paffhausen)2 and the popular preacher Abbot Tryphon (Parsons) of the All-Merciful Savior Monastery on Vashon Island, founded by Archimandrite Dimitry in 1986. Bishop Gerasim (Eliel) also talks about meeting him in 1981.3 He recalls that he witnessed the “gift of tears” in the Elder’s Jesus Prayer. His name has been on the Orthodox Church in America’s list of candidates for canonization for many years now. However, investigative files on the future archimandrite could not be found in Russian archives. Grateful venerators of Archimandrite Dimitry have prepared an icon of him, being convinced of the Elder’s holiness because of the many testimonies of his clairvoyance and spiritual help. In Russia, this ascetic is practically unknown, though his memory has been preserved in Valaam. And in 1997, there was an article in the journal of the Moscow Patriarchate about the Russian skete in Santa Rose that talked about Archimandrite Dimitry.4

Some of the Elder’s spiritual children and novices dispersed to various jurisdictions after his repose, but they’re all united by love for this man, who testified with his life to the truth of Orthodox and the height of the monastic calling.

This article was prepared on the basis of a report at a conference dedicated to the centenary of the foundation of the Solovki gulag.