As far back as 1794, monks from Valaam Monastery came to Alaska, marking the beginning of the preaching of Orthodoxy in the New World. In 2020, the Autocephalous (independent) Orthodox Church in America is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary. In his short overview, our expert has covered the glorious past of Orthodoxy in the USA, its troubled present and prospects for the future.

At the edge of the earth

Late in 1793, a group of eight monks from Valaam and Konevets Monasteries left St. Petersburg and nine months later arrived in the Aleutian Islands near Alaska. Thus they laid the foundation of the Kodiak, or Alaskan, mission and of Orthodoxy in the whole of America. A handful of missionaries were to bring the light of Christian faith to “the edge of the earth”: to the Pacific Islands and the cold region of Alaska.

The missionaries faced serious difficulties and were exposed to mortal dangers, from the severity of nature to the aggression of some local tribes. During the very first years the mission suffered heavy losses: in 1796, Hieromonk Juvenaly (Govorukhin), who had baptized several hundred indigenous Americans, was murdered by natives in mainland America; and in 1799, Bishop Joasaph (Bolotov), who had headed the mission, was shipwrecked along with two other clergymen and perished. Their lives can be called the first “seed” of Orthodoxy “cast” into the American soil.

The restored Church of the Ascension of the Lord on Kodiak

The restored Church of the Ascension of the Lord on Kodiak

Curiously enough, the mission faced the opposition of their own Russian compatriots.

Unfortunately, the riches of Alaska attracted a large number of dishonest merchants, industrialists and adventurers, who often deceived and exploited the Inuit and other natives. The Orthodox clergy defended their American flock, which provoked the dissatisfaction of many businessmen. Paradoxically, the Orthodox missionaries, whose arrival had become possible thanks to the Russian colonization of America, became true defenders of local native peoples from predatory actions of other “colonizers.” The missionaries showed native Americans the true spirit and the best qualities of the Russian people, namely love for God and their neighbors, respect for other peoples, patience and mercy.

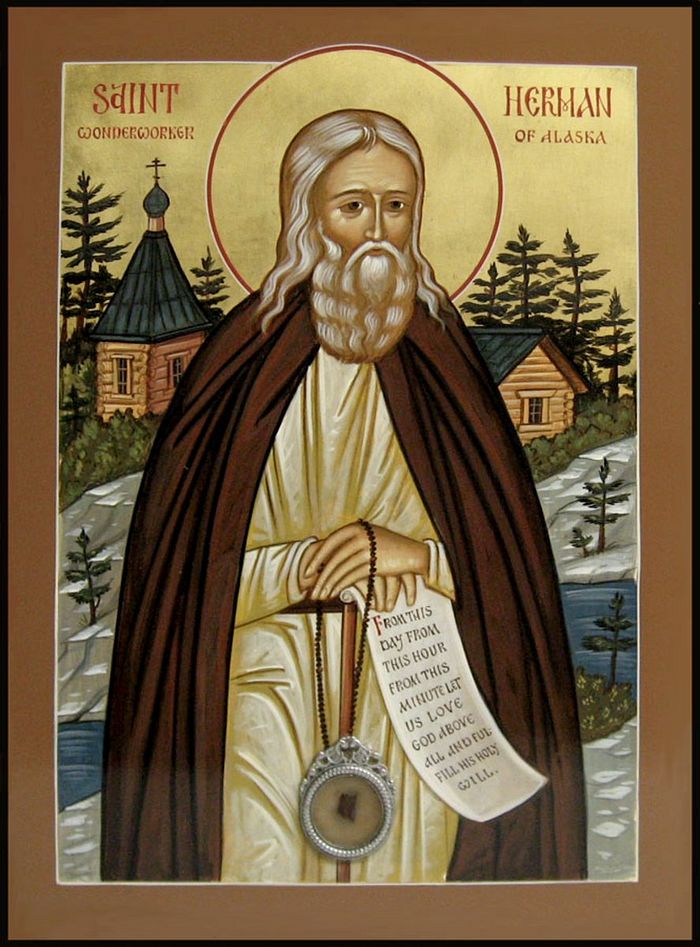

Perhaps the most striking embodiment of all these attributes was the most illustrious saint of America, Venerable Herman of Alaska (1751–1836). In many respects he resembled his great contemporary, St. Seraphim of Sarov. St. Herman radiated love, which encompassed and attracted people of all different backgrounds: Russians and Natives, the noble and the humble, the wealthy and the poor, adults and children. This love, coupled with his simple life (for example, the elder covered himself with a board that he called his “blanket”) and help to his neighbors, demonstrated genuine, living Orthodoxy. Semyon Ivanovich Yanovsky (1789—1876), Chief Manager of the Russian-American Company, recalled that his communication with St. Herman helped him find the true faith: “Through such continual conversations and by the prayers of the holy Elder, the Lord completely converted me to the path of truth.”1

Amazingly, wild animals sensed the elder’s holiness as well; there is evidence that among the saint’s friends and companions were ermines and a bear.

St. Herman displayed profound love for Alaska. “The Creator has given to our beloved fatherland this region like a new-born babe,”2 he would say. The saint regarded himself as “the most humble servant of the local peoples, and their nurse”.3

In 1970, St. Herman of Alaska was canonized by the Church. He is called in an Orthodox prayer “the adornment of Alaska and joy of America.” “For our happiness at least let us make a vow that from this day, from this hour, from this minute we shall strive to love God above all else and to fulfill His holy will4!” These words of Venerable Herman are relevant in all times.

The missionaries’ activities were not limited to the construction of churches, preaching and the celebration of services. Orthodox priests made an outstanding contribution to material and spiritual culture of Native Americans, the development of schooling and so on. In this respect the invention of the Aleut alphabet by Holy Hierarch Innocent (Veniaminov; 1797—1879) in 1826 was of key importance. A man of many talents, St. Innocent was much loved by indigenous Alaskans, to whose dwellings he would travel on an ordinary boat. Reaching out to the hostile Tlingit, he also displayed good medical skills—after he had introduced the smallpox vaccination, the epidemic among the natives was stopped. Thus St. Innocent gained the Tlingkit people’s confidence and in due course they discovered and embraced Orthodoxy.

Thus, the activity of Russian missionaries in Alaska marked the beginning of Orthodoxy on the American continent. The fruits of their labors are seen to this day, and the state of Alaska has the highest percentage of Orthodox Christians (five percent) in America.

Holy American Russia

America is a nation built by immigrants. In the late nineteenth century, immigrants from Russia, Greece, Serbia, Romania and other traditional Orthodox countries—but especially from Russia—were arriving in America in large numbers.

St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York City.

St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York City.

Initially, the Orthodox Church in America was called “the Diocese of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska”, and it united parishes in all the states. In the late nineteenth century, following a complicated period after the transfer of Alaska from Russia to the USA, the diocese had over 27,000 parishioners, twenty-nine parishes and forty-two priests. In subsequent years the diocese experienced steady growth; it catered to Russians, Aleutians, Orthodox Greeks, Serbs, Arabs and representatives of many other nationalities.

From 1898 till 1907 the diocese was headed by St. Tikhon (Belavin; 1865--1925), the future Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia. Thanks to his energetic labors the Orthodox Church in North America grew very rapidly. During that period the first Orthodox church was founded in Canada. In 1904, the beautiful St. Nicholas Cathedral was finished in New York City—and it was there that the Russian Orthodox diocese was transferred. The first Orthodox seminary was opened in 1905.

As early as 1906, St. Tikhon expressed the idea that the Orthodox Church in America should be granted autocephaly (independence). But his idea was not implemented until 1970.

Despite its somewhat “diasporal” structure, Orthodoxy in North America has always striven to be universalist by nature and open to all representatives of any nationality. During the consecration of St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York St. Tikhon said, “Our new temple… has missionary significance… Stand in the Orthodox Faith; keep your own traditions; love the temple of God. You are a chosen nation, a people chosen for His inheritance in order to proclaim to the people around us who are not Orthodox the wonderful light of Orthodoxy.”5

By the way, New York state has not only skyscrapers but also glorious countryside, spruce and birch old-growth (“virgin”) forests that you can easily take for those of the Moscow or Kaluga regions. It is amidst these forests, near Jordanville, that the Holy Trinity Monastery and the seminary are located. The golden domes remind you of Holy Rus’, or Russia—the country that the ancestors of many Orthodox Americans for one reason or another left many years ago. The main Cathedral of the Holy Trinity Monastery was built in the style of the tent-roof churches of Northern Russia.

The Holy Trinity Monastery was established in 1929 and it belongs to the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR). The restoration of Eucharistic communion between ROCOR and the Moscow Patriarchate took place in 2007 (it should also be noted that, apart from ROCOR, thirty parishes in the USA are stravropegic, meaning they are directly subordinate to the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia). For decades the monastery in Jordanville has been main holy place for Russian emigrants and a spiritual beacon of Orthodoxy in America.

Another great center is San Francisco with its marvelous Holy Virgin Cathedral (in honor of the icon, “Joy of All Who Sorrow”). This edifice was completed in 1964 through the efforts of St. John (Maximovitch; 1896—1966)—a celebrated hierarch of ROCOR, whose holy relics rest at the cathedral he built. St. John played a prominent role in spreading Orthodoxy among Europeans and Americans.

Metropolitan Tikhon (Mollard) of All America and Canada with Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia

Metropolitan Tikhon (Mollard) of All America and Canada with Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia

All in all, Russian Orthodoxy, which by its very nature is open and universal, has carried out its missionary task in America effectively, revealing the treasure of the faith to its inhabitants. It is logical that as a result of these efforts, Orthodoxy took root on this continent and the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) was granted autocephaly (independence) by the Patriarchate of Moscow in 1970. Today, the OCA has million-strong flock, and a vast majority of its parishioners are English-speaking Americans.

Mt. Athos… in Arizona

Of course, not only Russian preachers brought Orthodoxy to North America. The names of the Syrian St. Raphael (Hawaweeny; 1860–1915) of Brooklyn and the Serb St. Mardarije (Uskoković; 1889–1935)6 are worth mentioning here. After Russians, it was Greeks who made the largest contribution to the Orthodox mission’s development in North America. Thus, Archimandrite Ephraim (Moraitis; 1928–2019) from Philotheou Monastery on Mt. Athos established as many as nineteen monastic communities across the USA.

Fr. Ephraim, a disciple of the famous Athonite Elder St. Joseph the Hesychast, first visited North America in 1979. He was upset by the state of Greek communities there, the low level of their spirituality, corruption and other problems. He began to make frequent visits to the USA and later decided to move there forever in order to bring the spiritual tradition of Mt. Athos to that country.

Several decades ago, nobody could have imagined that soon one of the key landmarks of the state of Arizona would be a Greek Orthodox Monastery, the rule of which would concur with that of Athonite monasteries. The Monastery of St. Anthony the Great in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona was founded in 1995 by Archimandrite Ephraim. Its main church was built in the traditional Byzantine style.

The Monastery of St. Anthony the Great in Arizona

The Monastery of St. Anthony the Great in Arizona

The monks chose one of the remotest areas of the desert for their monastery, where they had no neighbors except for cactus, snakes and scorpions. With some difficulty they found water in the desert and drilled a well of a suitable depth. Thousands of trees were also planted on the territory of the monastery. Thus a spiritual and natural oasis appeared in the middle of an American desert.

“Each monastery is an outpost of God. The presence of our monasticism is a beacon in the New World,” Elder Ephraim used to say.

Today, St. Anthony’s Monastery is the second most visited place of Arizona. All different people travel there seeking spiritual help, and some even settle in the immediate vicinity.

The future of Orthodoxy in the USA

According to the Pew Research Center, Orthodox Christians in the United States make up roughly 0.5 percent of its total population. On the one hand, it is not much; but, on the other hand, Orthodoxy is one of the fastest growing religious groups in the USA, which, in addition, has its own traditions, saints and strugglers of piety. Orthodox churches and communities can be found in all fifty states of the USA and are no longer regarded as something exotic.

At the same time, there are lots of problems; notably, the Orthodox in America are divided into numerous jurisdictions. Apart from the OCA, there are structures of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Russian, Serbian, Romanian and other Local Orthodox Churches in the USA. Since in Orthodoxy a Local Church is not allowed to enter into the canonical territory of another one, Orthodox communities in America were originally united under the omophorion of the Russian Orthodox Church. This didn’t prevent Greeks, Serbs, Syrians and others from upholding their traditions while constituting a single whole. However, after the Russian Revolution of 1917, the unified administrative system collapsed and the unity achieved by St. Tikhon (Belavin) was undermined by the Patriarchate of Constantinople’s destructive activity. Orthodoxy in America still continues to suffer from the consequences of that meddling, and it is unlikely that they will be overcome soon.

Despite everything, Orthodoxy in the USA has its history and serious growth prospects. Holy Rus’ has driven its roots into the American soil so that it could become “Holy America”, if only on a small scale.

“I'm not saying that we Orthodox will ‘convert America’—that's a little too ambitious for us,”7 wrote Hieromonk Seraphim (Rose; 1934—1982), who was born into a typical American family, in his report entitled, “Orthodoxy in America”. But he rightly believed that living by our faith in accordance with God’s commandments is a real missionary factor that may arouse the interest of those who know nothing about Orthodoxy—for example, most modern Americans. “What if we who are Orthodox Christians began to realize who we are? —to take our Christianity seriously, to live as though we actually were in contact with the true Christianity? We would begin to be different, others around us would begin to be interested in why we are different, and we would begin to realize that we have the answers to their spiritual questions.”8

Also, for readers who interpret this as some sort of Russian propaganda against the Church of Constantinople, we sincerely regret that and hope that you can overcome it. This is simply a brushstroke historical article, without the many details, all of which are certainly open to subjective interpretation. But we cannot deny the historical fact that Orthodox mission came to American soil through the Russian Orthodox Church, and not the Greek Church, the latter of which undeniably resisted being under the omophorion of a Russian bishop in its members' new land. And undeniably, all the Orthodox Christians were at least temporarily united under the Russian Church. The rest, again, is subject to interpretation.