“History as a ‘potentially dangerous initiative’ in the EU.” This is the title of the article by the historian Darina Grigorova, who is a professor at Sofia University. The article was published on the Bulgarian website “Glasove” on February 5, 2024. It focuses on “European Historical Consciousness,” the resolution adopted by the European Parliament on January 17, 2024. It says, “The diverse and often contradictory historical narratives of European nations and states are making every effort to consider history from the political perspective as a difficult and potentially dangerous undertaking.” According to the resolution, “European historical consciousness,” with its fundamental goal of “a common historical memory,” is based not only on “European values” but also on “European conscience”. To clarify this topic, we offer a conversation with Professor Darina Grigorova.

—The resolution of the European Parliament attempting to generalize and standardize European history, and accordingly, the teaching of history, calls on historians to be “responsible” and make an “honest assessment” of EU policies of the past. A certain “European conscience”, and “European values”, are suggested as the reference point. What can you say about this?

—I’d say that there are no European values, but there are Christian values and, based on this, there are “responsible” and irresponsible historians. The transnational reading of history through the prism of the so-called European conscience is in the realm of ideological, not historical thinking. As for the resolution about the “European historical conscience”, it is a manual about transnational historical memory aimed at creating an ideal “transnational” or “supranational European”.

There are no European values, but there are Christian values, and based on this, there are “responsible” and irresponsible historians

As for the generalization of history, the present-day Eurocrats haven’t invented anything new. They recapitulated A. Lunacharsky and his notion of “teaching history in the communist school” (1918). Lunacharsky had no concept of “international conscience” (analogous to the “European” conscience), but he explicitly stated that the purpose of teaching history was “a moral idea, [part of] the communist regime, or I would say, a religion.” Communism is a religion where, according to Lunacharsky, “the proletarian ‘we’” was the “collective Messiah”. The educational policy of the Bolsheviks during the 1917 revolution and the following ten to fifteen years was based on this postulate. National history associated with patriotism and the Motherland got in the way of the ideology of internationalism. Russian history was banned and was not taught until 1922. The word “Russia” was written in quotation marks and the word “Patriotic”, adopted before the revolution as part of the name of the War of 1812, disappeared from the name of that war. It was a blow to historical memory and, at the same time, to faith. The Russo-Turkish war of 1877–1878 to liberate the Russians’ Bulgarian brothers in the faith was also subjected to redaction—in post-revolutionary Russia, monuments related to this war were demolished. This policy continued until the mid-1930s, when the threat of another war became clear and patriotism, along with the memory of national heroes-defenders, was needed again for the defense of the Motherland. This is what brought the national history back.

—Yes, despite the difference in ideologies, we can definitely draw parallels between the EU and the Soviet Union.

A famous science-fiction writer spoke about the necessity to destroy old history because it hinders the triumph of peace in the world

—I can give another example, this time from Great Britain. It’s from Herbert G. Wells, in his report, “The Poison Called History” written for the International Conference of History Teachers convened in London by the League of Nations. The famous science fiction writer spoke of the need to destroy old history because it hinders the triumph of peace in the world. It’s all in the name of peace. Wells spoke not of internationalism, but of cosmopolitanism. According to his opinion, the future lies in unified governance. That is why we need universal history, with one textbook, and historians all over the world should be trained solely on this textbook. He concludes his report:

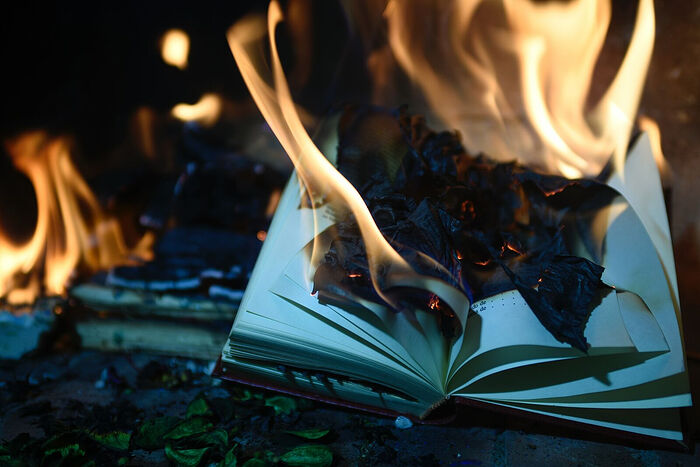

“Hopes for universal peace will not become real if we don’t train people to accept the realities of new history. So let us get down to business—firstly, in our own minds and then in the universities, the encyclopedias, and the schools. Let us offer the burnt sacrifice of textbooks of old history as our contribution to the building of Cosmopolis—a natural, and currently simply necessary, Universal Brotherhood of Men.”1

—In order for such ideas to work, one should generalize and bring to a common standard not only history, but also religion.

—Economically, Western Europe has already absorbed and digested Eastern Europe, but in spiritual terms, a greater part of Eastern Europe still remains Orthodox. In other words, it is incompatible with the Western European conscience and historical memory.

—It is obvious why this declaration has appeared in our days, as it openly speaks about the “latent competition and partial incompatibility” of memory in Eastern and Western Europe, disinformation, and “Russian historical revisionism,” and about the “protection of democratic memory.” But what reaction can it trigger in Europe proper, in both its western and eastern parts?

—Attempts to destroy national memory can lead to the opposite effect—nationalism, or even Nazism, and destabilization. It will not be possible to squeeze history into the Procrustean bed of yet another ideology. So, this utopian project with its possible consequences is entirely on the conscience of Eurocrats. The European resolution, through the image of its enemy—Russia in this case—is trying to introduce censorship on the freedom of historical perspective. But globalism may also become an enemy, and then we have the danger of the rise of nationalism.

The Balkans have always been a unique region. Historical memory is very strong here. Including its ties with Russia. Will the resolution be able to handle this?

—In the Balkans, history is an important factor. And the fact that we are really keen on our history can be regarded as a plus—it helps to preserve our identity and protect us from dangers from Brussels. However, it does not protect us from nationalism.

The idea to replace our national holiday, the Day of Liberation of Bulgaria from the Ottoman yoke, has failed

This whole Euro thing is like playing with fire. There is resistance. The idea of replacing our national holiday, the Day of Liberation of Bulgaria from the Ottoman yoke, the major feast of our country and its people, has failed. This year, many more people than usual came to Shipka on March 3. But this holiday has to do with our liberator, which was Russia. All Orthodox churches in Bulgaria proclaim at every liturgy at the Great Entrance:

“May the Lord remember in His Kingdom our liberator Tsar Alexander II Alexandrovich in blessed repose, all the Orthodox leaders and soldiers who laid down their lives on the battlefield for the faith and liberation of our Motherland.”

The spiritual presence of Russia in the Balkans, by way of history and Orthodoxy, has nothing to do with geopolitics and remains a constant. This is certainly not something the European Resolution can cope with.