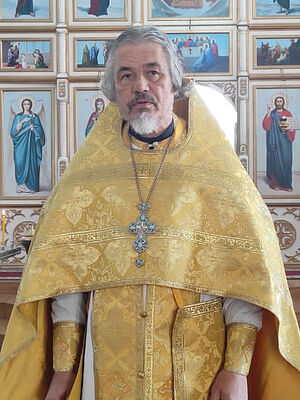

Clergy and parishioners of the Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Photo: Vk.com/pravoslavie_mn

Clergy and parishioners of the Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Photo: Vk.com/pravoslavie_mn

The revival of parish life in the 1990s

Reviving its activity in Mongolia in the 1990s, the Russian Orthodox Church, according to Priest Nikolai Kornienko, “did not set itself the task of converting the native population in Mongolia.”1 At the initial stage, it really needed to register a parish and resume parish life after a long interval. The further goal of the Church was to pastor the Russian inhabitants (or rather, all Russian-speaking residents) of Mongolia. This population group includes both Russian specialists who came here on business and those who are conventionally called “local Russians” —descendants of immigrants from Russia in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries who settled down in their new homeland on a permanent basis. Legally, in the documents the group of Russian citizens permanently residing in Mongolia are referred to as “Russian compatriots”, who are united in the non-profit public organization the Coordination Council of the Organization of Russian Compatriots in Mongolia (CCORCM).

It was active representatives of the “local Russian” community of Ulaanbaatar who in 1995 first turned to V.A. Dunayev, chairman of the Society of Russian Citizens Living in Mongolia, and A.V. Fedulov, adviser to the Embassy of the Russian Federation in Ulaanbaatar. As a result of preliminary negotiations, compatriots decided to personally appeal to His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II of Moscow and All Russia with a request to revive the Orthodox parish in the country. After that, in February 1996, care of the revived Orthodox community of Ulaanbaatar through a special letter from the Chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations, Metropolitan Kirill of Smolensk and Kaliningrad (now His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia), to Bishop Pallady of Chita and Transbaikalia was entrusted to Priest Oleg Matveyev, rector of the active Orthodox church closest to Ulaanbaatar—of the Dormition of the Mother of God in the city of Kyakhta, the Buryat Republic.2

Archpriest Oleg Matveyev As a result of the appeal, for the initial organization of the life of the Orthodox community and preparatory work for the registration of the parish, on April 1, 1996, a delegation of lay-people and clergy left for Mongolia. It included Archpriest Igor Arzumanov, head of the Buryat Deanery of the Chita and Transbaikal Diocese, Priest Oleg Matveyev, rector of the Dormition Church in Kyakhta, and the historians O.V. Bychkov (Ph.D in History, Academic Secretary of the Buryat Deanery) and A.D. Zhalsarayev (Ph.D in History, advisor to the Buryat Deanery). It was Fr. Oleg Matveyev who would pastor the Mongolian flock until the official registration of the stavropegic parish (in the DECR MP) and the appointment of Fr. Anatoly Fesechko as permanent rector here (December 25, 1997). Over about a year and a half he would make nine trips to Ulaanbaatar3

Archpriest Oleg Matveyev As a result of the appeal, for the initial organization of the life of the Orthodox community and preparatory work for the registration of the parish, on April 1, 1996, a delegation of lay-people and clergy left for Mongolia. It included Archpriest Igor Arzumanov, head of the Buryat Deanery of the Chita and Transbaikal Diocese, Priest Oleg Matveyev, rector of the Dormition Church in Kyakhta, and the historians O.V. Bychkov (Ph.D in History, Academic Secretary of the Buryat Deanery) and A.D. Zhalsarayev (Ph.D in History, advisor to the Buryat Deanery). It was Fr. Oleg Matveyev who would pastor the Mongolian flock until the official registration of the stavropegic parish (in the DECR MP) and the appointment of Fr. Anatoly Fesechko as permanent rector here (December 25, 1997). Over about a year and a half he would make nine trips to Ulaanbaatar3

Remarkably, the first organizational meeting of the Buryat clergy and academics with the Orthodox in Mongolia took place on April 3, 1996—that is, the day before the famous date on which the first Divine Liturgy had once been celebrated in the consulate Church of Urga.

Speaking about the tasks of the revived parish, in a report to Metropolitan Kirill, Chairman of the DECR MP, Archpriest Igor Arzumanov wrote that it was necessary to “preserve the Orthodox faith among Russian emigrants” and “organize missionary work of Russian citizens among the native population.”4

Fr. Oleg Matveev performed the first prayer services and Baptisms in private apartments and hotels, since the nascent Orthodox parish had neither premises nor a plot of land. Those pressing issues were resolved thanks to the close cooperation between the DECR, the Chita and Transbaikal Diocese, the Russian Embassy in Mongolia, the Russian Trade Mission in Mongolia, the Mongolian leaders and all the concerned faithful of the country.

On November 27, 1996, as a result of the efforts of Church hierarchs, along with the secular authorities of Russia and Mongolia, the Ministry of Justice of Mongolia registered an Orthodox parish, which was accepted into the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. Some time later, on March 16, 1997, Priests Igor Arzumanov and Oleg Matveyev celebrated the first Divine Liturgy in Ulaanbaatar in many years and on December 22, 1997, the DECR approved the Charter of the Holy Trinity Parish of Ulaanbaatar.5

By the decision of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church on December 25, 1997, Archpriest Anatoly Fesechko, a cleric of the Vladimir and Suzdal Diocese, was appointed rector of the Holy Trinity Parish in Ulaanbaatar. Fr. Anatoly's assignment was no coincidence: he had studied at the Post-Graduate Department at the DECR, where priests were trained to serve abroad. After graduating from the Post-Graduate Department, Fr. Anatoly was invited to go and serve in Ulaanbaatar.6

“Vneshintorg” OJSC transferred to the use of the Holy Trinity Parish a two-story residential building for eight apartments with an area of over 4840 square feet, located on the territory of the Russian Trade Mission in Mongolia. After the reconstruction and repair of the building, a house church, premises for church needs and an apartment for the rector's family were equipped. A bell-tower was built on the roof above the house church.

In August 1998, Fr. Anatoly reported to the DECR that the number of parishioners had reached forty, and on Sundays between eight and fifteen Orthodox Christians prayed in church. About 100 people worshiped on Pascha. Over the first eight months ten local Russians and employees sent from Russia were baptized. Gradually, by 2003, the Ulaanbaatar church had between twenty-five and thirty parishioners.7

In addition to the capital of Mongolia, an Orthodox community was formed in the city of Erdenet in the north of the country, where a large Russian-speaking community lived. These were mainly employees of the Erdenet Mining and Refining Business and their families. Church services and services of need were celebrated there by visiting priests on a regular basis until the late 2010s. As the Orthodox population in the city dwindled, the priest no longer traveled to the city. The remaining practicing Orthodox in the city began to travel to Ulaanbaatar themselves for the major feasts, such as Pascha and the Nativity of Christ. There were also plans to open a parish in the city of Darkhan, which has a Russian Consulate-General, but they were never implemented due to the small number of Orthodox believers.

It is noteworthy that Fr. Anatoly, in addition to his fluent English, mastered the Mongolian language during his life in Mongolia. Nevertheless, among the difficulties that he had to face in Mongolia as a missionary, Fr. Anatoly mentioned services in Church Slavonic, a language “which was sometimes incomprehensible to Russians, let alone Mongolians”.8

An important milestone in the life of the parish at its initial stage was the archpastoral visit to Ulaanbaatar of the then DECR Chairman, Metropolitan Kirill of Smolensk and Kaliningrad, from July 7 to July 10, 2001. He consecrated the house church and blessed the foundation stone of a new separate Orthodox church, the construction of which in the area adjacent to the parish building was planned by Fr. Anatoly, together with parishioners and representatives of Russian business, having carried out huge preparatory work. But the main task of the church construction was entrusted by God to the next rector of the parish, Archpriest Alexei Trubach.

For health reasons and in connection with the need for his children to continue their education in higher educational institutions in the Russian Federation, Fr. Anatoly appealed to the Church hierarchy to release him from the post of rector. On April 20, 2005, the Holy Synod decided to release Archpriest Anatoly Fesechko from the obedience of rector of the Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar.9

So, from the second half of the 1990s regular services resumed in Mongolia—first in apartments, and then on the territory of the parish in the house church. At the same time, the life of the multinational Orthodox community was being revived, and its internal problems were being solved. All this was an important part of the mission, which was consistent with the Concept of the Revival of Missionary Activity of the Russian Orthodox Church, adopted by the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church on October 6, 1995 and valid until 2007. Its section 2, among other things, it was stated that “the meaning of the mission of the Orthodox Church is that it is aimed not only at communicating intellectual beliefs and moral ideals, but at communicating the experience of Communion with God, the life of the community existing in God.”10

Holy Trinity Church, Ulaanbaatar From a chapter of the extensive monograph by Priest Nikolai Kornienko, which he wrote together with A.M. Plekhanova, we can glean a lot of information about the intensity of passions that accompanied the revival of the life of the Orthodox community in Ulaanbaatar, about systemic internal church problems manifested by a confrontation between the clergy and the individual laypeople who had been begun the parish rebirth in Mongolia. These passing stories superficially interested journalists as something sensational; but those familiar with the no less “scandalous” circumstances of the birth of the Church of Christ, described in the first chapters of Acts (the deceit of Ananias and Sapphira, the murmuring of the Greeks against the Jews because of the daily ministration [Acts 6:1], the sin of Simon the Magus, etc.), would not be surprised by this.

Holy Trinity Church, Ulaanbaatar From a chapter of the extensive monograph by Priest Nikolai Kornienko, which he wrote together with A.M. Plekhanova, we can glean a lot of information about the intensity of passions that accompanied the revival of the life of the Orthodox community in Ulaanbaatar, about systemic internal church problems manifested by a confrontation between the clergy and the individual laypeople who had been begun the parish rebirth in Mongolia. These passing stories superficially interested journalists as something sensational; but those familiar with the no less “scandalous” circumstances of the birth of the Church of Christ, described in the first chapters of Acts (the deceit of Ananias and Sapphira, the murmuring of the Greeks against the Jews because of the daily ministration [Acts 6:1], the sin of Simon the Magus, etc.), would not be surprised by this.

The causes of parish conflicts in Ulaanbaatar in the late 1990s and the early 2000s had for the most part a spiritual nature, hidden and barely noticeable behind external things. Many years of separation of Orthodox people in Mongolia from Church life, their life in a non-Orthodox environment—all this required serious missionary work to restore parish life in Mongolia. Most of the organizational and legal issues of that process were resolved by the clergy of the Chita and Transbaikal Diocese (Priests Igor Arzumanov and Oleg Matveyev) and the first rector of the revived parish, Fr. Anatoly Fesechko. A new stage was beginning.

Orthodoxy in Mongolia at the present stage

In April 2005, Fr. Alexei Trubach, who had previously been rector of St. Sergius Parish in Johannesburg (South Africa) and had experience of missions to India and Nepal, was appointed rector of the Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar. Fr. Alexei was fluent in English, and in Ulaanbaatar in a short span of time he mastered colloquial Mongolian, and read and translated (with a dictionary) from Mongolian into Russian.

The entire ministry of Fr. Alexei in Mongolia was associated with active missionary work. First of all, the new rector continued the remodeling of the parish building, equipping rooms for the Sunday school, the refectory and classrooms on the ground floor.

The key event in the life of the parish was the construction of the Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar in 2006-2009, which is still the only Orthodox church in the whole country. On June 21, 2009, Archbishop Mark (Golovkov), Secretary of the Moscow Patriarchate for Institutions Abroad, performed the Great Consecration of the church and headed the Divine Liturgy in it. In July 2009, a plot of land with an area of 0.83 hectares adjoining the church was transferred to the ROC for free use for a period of sixty years with the right to subsequent extension.

The construction of the Orthodox church in Ulaanbaatar is certainly a milestone in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church in Mongolia. Together with the adjoining landscaped park area, it is one of the most significant and architecturally striking buildings in the city. It is a kind of preaching of Orthodoxy in stone and gold.

The presence of only one Orthodox priest in the whole of Mongolia limited the scale of missionary activity to a certain extent. Nevertheless, Fr. Alexei Trubach’s service as rector undoubtedly contributed to the intensification of parish activity in all its possible forms.

One of the main methods of work at the beginning of Priest Alexei Trubach’s ministry in Ulaanbaatar was the inculturation approach—that is, the “principle of the Church reception of culture”, “coordination of means and methods of missionary work with the specifics of different cultures, traditions and customs,”11 “the use of all forms of existing culture to express the main aspects of the Biblical worldview.”12 In the context of Orthodox mission this approach was revealed only in part.

Gradually, Fr. Alexei began to move away from this approach, since in Mongolia in order to preach Orthodoxy you did not always need to refer to the criteria of local culture. Some individual Mongolians converted to Orthodoxy because for them faith was associated with Russian culture, the Russian language and Russian civilization in general, for which they had a affinity:

“Ancient Orthodox Christianity is the inspirational core of Russian culture, and the Mongolians, embracing Russian Orthodoxy, as experience has shown, are gradually catechized after getting baptized. And although it is a long process that takes decades, in the long run it will not produce Russified Mongolians, but Mongolians who will adopt universal Orthodox Christianity while preserving their own national identity. This is unlike Western missionaries, who re-educate newly converted Mongolians into ‘South Koreans’, ‘Americans’, etc.”13

Virtually all the activity of the ROC among the native population in Mongolia can be characterized as an “external mission”, which is carried out among a people whose traditions and customs do not have Christian foundations and periods. Mongolia is also home to a large number of peoples who are traditionally, (by definition), perceived as Orthodox. These are local Russians as well as representatives of other ethnic groups (Belarusians, Ukrainians, Serbs, Georgians, etc.). It is among the Orthodox “by definition” that “internal” forms of mission are carried out, but in the foreign environment, in practice, a creative combination of all available methods of preaching the Gospel is implemented.

For example, the educational form of mission, in addition to the generally known preparation for the sacrament of Baptism through participation in Church services, catechetical talks and subsequent instructions, was carried out under Fr. Alexei through active social service, “for the power of Christian love is clearly manifested in works of charity.”14

In 2007, under the auspices of the Russkiy Mir Foundation, a Russian Cultural Center for children was opened in the parish, where there were Russian language, ballet, fine arts, pottery and computer classes.15 The cultural center functioned until the early 2010s. In 2011, a four-year Anima art school was opened within the walls of the parish building. Today there are around fifty students and thirteen teachers there.

In 2007–2010, there was the Troitsa (“Trinity”) bandy club at the church. The team included Mongolian and local Russian youths. During that period four players were converted to Orthodoxy, two of whom were blessed to study at the Moscow Theological Seminary, though they did not complete their course of study.

In 2010, a gym with an area of 5510 square feet was built on the parish territory not only for people of the Bayanzürkh district of Ulaanbaatar, where the parish is situated, but also for the entire 1.6 million population of the capital. It is one of the few well-equipped and accessible gyms with up-to-date sports equipment, a good ventilation system, and showers. In addition to sports events, at first cultural events were organized in the gym as well (concerts took place, films were screened and educational lectures were held16). Currently, the building is divided into two parts, in one of which fitness training is held, and in the other–sambo, judo, boxing and Mongolian wrestling.

The Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar, the parish buildings, the gym and the park area around the church became a place that was often visited by many officials, both Russian and others. Among the hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk (Alfeyev; the DECR Chairman between 2009 and 2022, now Metropolitan of Budapest and Hungary) visited the parish September 18–19, 2012; and Archbishop Anthony of Vienna and Budapest (Sevryuk; then head of the Moscow Patriarchate's Administration for Institutions Abroad; now Metropolitan of Volokolamsk, the DECR Chairman since 2022) on February 23–24, 2019.

To be continued…