In February 2016, the Russian Orthodox Church’s Bishops’ Council made amendments to the ROC Charter, according to which Mongolia was included in the canonical territory of the Russian Orthodox Church. It demonstrates a special attitude towards Mongolia on the part of the ROC. That amendment was explained both by the historical position of Mongolia in the Russian Empire’s sphere of influence and by the present time; since the early 1990s, none of the Local Orthodox Churches, except the Russian Church, has sent missionaries to Mongolia.

Over the fourteen years of Fr. Alexei Trubach’s service as the rector (2005–2019), energetic missionary activities in various fields were organized in Mongolia (mainly in the cities of Ulaanbaatar and Erdenet). As a result, a strong multinational Orthodox community has been built in Mongolia, consisting not only of Russian-speaking citizens of Russia and Mongolia, but also of those Mongolians and citizens of third countries for whom modern Russian is as foreign and incomprehensible as liturgical Church Slavonic.

The expectations of Fr. Eugene Startsev (then rector of the Church of the Hodegetria Icon in Ulan–Ude, now a cleric of the Irkutsk Diocese), which he expressed during his trip to the Khalkhin Gol in August 2005, were surprisingly fulfilled:

“Batiushka labors absolutely selflessly in this field… He is zealous in his ministry. He serves alone in the church—he censes, reads and sings himself. Fr. Alexei has extensive plans. I think that for the most part they are destined to come true, because he is a serious priest. I am sure that he will have a choir and a reader.”1

Indeed, on the foundation laid by the clergy of the Chita and Transbaikal Diocese and by the first rector of the parish, Archpriest Anatoly Fesechko, Archpriest Alexei arranged a well-organized, systematic liturgical and extra-liturgical life; a church choir was formed from professional Mongolian singers—a rare phenomenon for modern Russian churches abroad. Three acolytes served in the church altar, and services began to be translated into Mongolian.

During the Divine Liturgy, the Great Litany and antiphons began to be proclaimed and sung in Mongolian, the Epistles and the Gospel are read in three languages: Church Slavonic, Mongolian and English. This principle of addressing the country’s local population in their native language is even implemented in the paintings of the Holy Trinity Church, on the walls of which there are the initial words of the Creed in Mongolian. The Third and the Sixth Hours are served in Mongolian as well.

In addition to the celebration of all services according to the Typikon, a sports and cultural and educational center began to function stably in the parish. From December 20082 to January 2013, the Troitsa (“Trinity”) parish newspaper was printed in Russian and Mongolian. Catechetical literature (by St. Nikolaj [Velimirovic] of Zica and Priest Georgy Maximov, our contemporary) and prayer-books (the morning and evening prayer rules) were translated into Mongolian. Besides, since the late 2006 there has been a parish website, which is currently being modernized. In addition to the website, the parish's social media page appeared under the next rector, Priest Anthony Gusev.

Archpriest Alexei Trubach fulfilled all the tasks he had been entrusted with and on May 30, 2019, due to the end of his mission term, by the decision of the Holy Synod, he was released from his obedience as rector of the Holy Trinity Church in Ulaanbaatar.

Priest Anthony Gusev with his wife Anastasia and son Timothy Priest Anthony Gusev, a cleric of the Orenburg Diocese, was appointed next rector by decree of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia on July 5, 2019. Prior to sending him to Mongolia, the Church hierarchy charged him with a task that may seem ordinary: “to preserve the parish.” Providentially, it was six months before mankind was faced with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Priest Anthony Gusev with his wife Anastasia and son Timothy Priest Anthony Gusev, a cleric of the Orenburg Diocese, was appointed next rector by decree of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia on July 5, 2019. Prior to sending him to Mongolia, the Church hierarchy charged him with a task that may seem ordinary: “to preserve the parish.” Providentially, it was six months before mankind was faced with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Having experience in organizing and carrying out design and repair work, in the first months after his arrival in Ulaanbaatar Fr. Anthony repaired the parish apartment, the roof of the parish building and the gym (ventilation, lighting) and arranged for the exterior whitewashing of the building and the church. Later, as funds accumulated, the heating system inside the church was improved, and the furniture in the sanctuary was partially replaced.

The task that the Church hierarchy had set before Fr. Anthony became particularly relevant during the period of strict lockdowns and other precautionary measures imposed in Mongolia for quite a long time in response to the spread of coronavirus. From February 2020 to September 2021 (with rare short intervals) the church was closed for public worship and even for visitors. Movement around the city during lockdowns was limited, many parishioners fell ill, and most residents of the country were simply afraid to leave their homes. In such circumstances, to keep people in a prayerful mood, strengthen their faith, organize services, and provide an opportunity for Orthodox parishioners to attend them was an absolutely new challenge that the Russian Orthodox Church in Mongolia faced.

Thanks to the personal participation of the Ambassador of the Russian Federation to Mongolia I.K. Azizov and the close ties established in Ulaanbaatar by Fr. Anthony Gusev, it became possible to celebrate the Divine Liturgy during lockdowns, first in the cinema hall of the Russian Embassy building in Mongolia, where Pascha was celebrated in 2020, and then in the Trade Mission’s outbuilding. Thus, active interaction of the Church and State allowed the Orthodox in Mongolia even during restrictions to participate in the most important Church sacrament—the Eucharist.

With the support of Russian firms and agencies of Russian companies, food packages were collected twice a year in the parish in order to support socially vulnerable segments of the population, whose numbers had noticeably increased owing to the stresses caused by measures to combat COVID-19. In addition, in July–August 2021, an extended-day group was temporarily organized within the walls of the parish building for children of Russian compatriots who, under quarantine measures, had to stay at home all the time and were unable to attend preschool educational institutions.

Another form of social service has been the regular collection of humanitarian aid on the territory of the parish for people in the Special Military Operation (the SMO) zone with the active participation of the Coordination Council of the Organization of Russian Compatriots in Mongolia.

We should also mention apologetic work carried out by the Russian Orthodox Church in Mongolia. In Orthodoxy “apologetics” is understood as “defending the dignity of Christian teaching as the only true one before those who deny it” and “revealing and defending Christian teaching with the help of means used by adherents of other faiths and non-believers.”3

It is known that a broad range of Protestantism flourishes in Mongolia. According to some outdated information, the most numerous are evangelicals (having about 36,000 people, 400 communities, and forty-seven NGOs) and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons; around 8,000–10,000 members, thirty branches, and over 160 missionaries).4

In 2010 the comprehensive encyclopedia called Religions of the World by the American religious scholar J. Gordon Melton (a member of the United Methodist Church) estimated that Christians make up 1.7 percent of the country’s population (47,100 adherents).5 According to the 2020 census, the number of Christians in Mongolia among those over the age of fifteen has dropped to 2.2 percent6. According to a survey conducted by the Institute of Philosophy of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences, 2.4 percent of the population identify themselves as Christians among the country’s religious citizens.7

In addition, certain conditions for the position of Orthodoxy in Mongolia are imposed by some articles of the Mongolian Law “On the Relationship Between the State and Religious Institutions”, which has already been considered in part 1. It regulates missionary activities of preachers of “non-traditional” religions. So for example, according to paragraph 2 of Article 3, “it is prohibited to compel citizens to embrace or not embrace a faith”; according to paragraph 7 of Article 4, “it is prohibited to hold organized events to spread religion from abroad”; according to paragraph 8 of Article 4, “the State regulates the total number of clergy and the locations of churches.”8 This circumstance entails the annual practice of extending State registration of religious organizations, including Orthodox parishes.

The process of annual re-registration of a religious organization is rather complicated, lengthy and requires certain skills. Nevertheless, recently some representatives of the capital city authorities have met the Holy Trinity parish halfway, moving away from their notorious formalism. It is largely thanks to both the diplomacy of the rectors of the Orthodox parish and the authorities’ sincere amazement: “It appears that, unlike many Protestant organizations, the Orthodox in Mongolia just pray without participating in other, non-religious activities.”9

The abundance and diversity of Christian teachings in Mongolia creates a rich polemical environment for Orthodox missionaries. Orthodox clergy and laypeople regularly talk about the faith with the capital city residents and in the country in general not only at their parish, but also in everyday life situations. As a result, some Mongolians, Russians, and citizens of third countries permanently residing in Mongolia convert to Orthodoxy. Besides, many Mongolians living in Ulaanbaatar who are located outside the area where the Russian church is situated learn about the Holy Trinity parish’s existence and about Orthodox Christianity solely from such conversations.

The population of the country is quite tolerant of and somewhat indifferent to the vestments of Orthodox priests, so over the fourteen years of his ministry in Mongolia Fr. Alexei Trubach always walked freely around the city in his cassock, which, according to him, was also a form of mission. Fr. Anthony adheres to a similar practice.

During the two modern stages, under Priests Alexei and Anthony, regular talks were held with Mongolian residents who had suffered after going to shamans and turned to Orthodox clergy for spiritual help and support. This applied both to unbaptized Mongolians (some of whom were later baptized, but in most cases continued to adhere to their beliefs and to turn to shamans for “help” again) and to baptized but non-religious local Russians, who culturally partially merge with the native population of Mongolia, the spirituality of which is mainly a blend of Buddhist beliefs and shamanic and other pre-Buddhist cults.

Under Fr. Alexei Trubach, the Russian Orthodox Church in Mongolia established warm, friendly relations with both the head of the largest local Buddhist sangha (the Mongolian Buddhist Association, head abbot of Gandantegchinlen Monastery in Ulaanbaatar) D. Choijamts (served from 1993 to 2023) and the Catholic Bishops Wenceslao Padilla (2002–2018) and his successor Giorgio Marengo (cardinal since August 2022) and other clerics of the Roman Catholic Church.

Since 2021, there has been a regular practice of organizing and holding interfaith dialogues (Orthodox-Catholic, Orthodox-Buddhist, and other round tables) and mutual visits on the occasion of commemorative and solemn events.

During his five-year ministry, Fr. Anthony, despite the challenges of the pandemic, did not interrupt his liturgical activity, organizing the collection of humanitarian aid for both poor residents of Ulaanbaatar (during lockdowns), regardless of their denominations, and for people in the war zone, repairing the parish building, the gym and arranging the whitewashing of the church (which hadn’t been whitewashed since the time it was built). He takes an active part in official events of the Russian Embassy in Mongolia and the Russkiy Dom (“Russian House”) Russian Scientific and Cultural Center, cooperates with many Russian and Mongolian public organizations, involving all interested citizens in the development of parish life, maintaining relations with members of numerous non-Orthodox denominations in the country. Moreover, together with representatives of Russian search expeditions he more than once visited the battlefields in Dornod Aimag (province), where memorial services were celebrated for those who were killed there.

A gym continues to function on the territory of the parish, where fitness training and martial arts training sessions are held; the Anima art school is still open, and among its students there are children with various congenital diseases. The parish has a Sunday school for children, where parishioners teach. Some Sunday school students were born in Mongolia from both Russian and mixed marriages, and were baptized within the walls of the Holy Trinity Church. Regularly after the Sunday Divine Liturgy and the subsequent meal, reading and study of the Holy Scriptures is organized.

The number of parishioners is growing and is not limited only to Russian-speaking citizens of Russia and Mongolia. According to Fr. Anthony, today there are 150-200 parishioners in the country’s only Orthodox church, with thirty to seventy people praying at Sunday services—these are Russians, Mongolians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Greeks, Serbs, Britons, Americans, Georgians, Poles, Canadians and New Zealanders.10

The great merit of the Russian Orthodox Church in Mongolia is the integration into Church life of baptized people—those who are usually perceived as Orthodox “by definition”. Many local Russian specialists permanently residing in Mongolia, as well as those on business trips from Russia, without adhering to any particular religious system (even if they are baptized), are quite easily drawn into all sorts of local Buddhist teachings, Shamanistic and Parabuddhist cults.11

But not all plans have been implemented so far. For example, the large-scale reconstruction of the church park area and the construction of a chapel-burial vault in the southwestern part of the parish area, in which the remains of Soviet soldiers who fell in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in 1939 will be buried, are still planned.

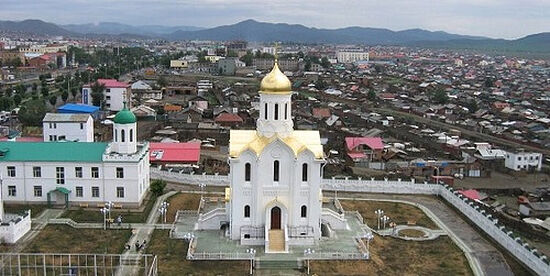

Thus, the three rectors of the Holy Trinity Parish of Ulaanbaatar at the present stage of the history of Orthodoxy in Mongolia have successfully solved the specific tasks assigned to them by God. Under Fr. Anatoly Fesechko, a house church was equipped, the parish building was rebuilt, and the foundation of the Orthodox community, which exists in the parish to this day, was laid. Under Archpriest Alexei Trubach, the church was built, the surrounding area was beautified, a gym appeared and liturgical and extra-liturgical parish life was organized in all possible forms. Under Priest Anthony Gusev, the parish withstood the unprecedented test of the pandemic, and Orthodox residents of the capital could participate in joint services during lockdowns, the community was preserved and new members are still joining today.

The results and prospects of 160 years of service

The purpose of this article was not only to demonstrate some key episodes related to the history of Orthodoxy in Mongolia ahead of the 160th anniversary of its existence, but also to show that the example of Mongolia and its Orthodox community clearly shows the universal nature of the Orthodox faith, where there is neither Greek nor Jew (Col. 3:11); neither a local Russian, nor a Mongol, nor a Russian diplomat, nor a descendant from a mixed marriage (whether between a Russian and a Mongolian or a Mongolian and a Briton)…

In the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries, the imperial mood of Mongolian khans allowed them to become closer to Orthodox preachers, who felt comfortable in the capital of the empire—Karakorum. A natural development of these relations was the establishment of the Diocese of Sarai in the Golden Horde, which bound together the Horde and Russia, performing certain diplomatic mediation functions for the Byzantine Empire and the Russian princes alike.

The clergy of the Diocese of Sarai and other dioceses bordering the Horde, despite their secure existence under imperial patronage, were quite passive in mission. Despite this, the scarce (in terms of numbers) preaching of Orthodoxy had a wholesome effect on the hearts of some individual Horde representatives. And speaking about some of the major figures of the joint Russo-Mongolian past, we can’t ignore their confession of the Orthodox faith. First of all, these are three saints: the Right-Believing Prince Alexander Nevsky, the Venerable Tsarevich Peter of the Horde and the Holy Hierarch Alexei of Moscow.

The history of Orthodox Mongolia of the nineteenth–early twentieth centuries acquaints us with the great spiritual labors of a number of priests who bound together the churches of the Irkutsk Diocese, Transbaikalia, Mongolia and China, and in most cases remained faithful to God to the death. And if readers have a desire to pray for the repose of the souls of the Orthodox clergy of Urga, it would be the best tribute to Archpriests John, Mily and Fyodor, Hieromonks Sergei, Gerontius and Cornelius, Priests Alexei, Vsevolod, and two Nicholases.

In February 1998, Metropolitan Kirill of Smolensk and Kaliningrad, Chairman of the Department for External Church Relations, in a letter to His Eminence Innokenty, Bishop of Chita and Transbaikalia, written on the occasion of the appointment of permanent rector to Ulaanbaatar and in gratitude to Priest Oleg Matveyev, who had temporarily pastored the Orthodox faithful in Mongolia, expressed the hope that “in the future the spiritual bonds traditionally uniting the Orthodox parishes of Transbaikalia and Mongolia will be preserved.”12 Today the Holy Trinity Parish of Ulaanbaatar has strong friendly relations with the Orthodox parishes of the Buryat Metropolia, with the clergy concelebrating and parishioners making mutual pilgrimages. To date, a strong multinational and multilingual community has developed in Mongolia on the basis of a single Orthodox parish, which should become the foundation and model for further missionary work in this country.