Alaska, formerly known as Russian America, continues to preserve its Russian Orthodox roots, despite having become a part of the United States in 1867, almost 160 years ago. We spoke about this phenomenon with filmmaker Simon Scionka, a subdeacon at Holy Theophany Church (OCA) in Colorado Springs, who with his colleague Silas Karbo produced a fascinating documentary about Orthodoxy in Alaska called, “Sacred Alaska”.

—Simon, why is Alaska sacred?

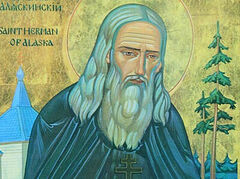

—Why is Alaska sacred? For many reasons. Orthodoxy in America is very interesting, it is multiethnic and multicultural. It comes from different paths and angles. But arguably, Orthodoxy first came to America through Valaam monks, including St. Herman, who brought it from Russia, from Valaam, to Kodiak Island and ultimately to Spruce Island where he lived. What we see here is real holiness.

Simon Scionka I would say that Spruce Island is America’s Holy Land in some ways. If you can, go there and experience it—through St. Herman’s prayers and through his holiness, through his ministry and service to God, we really see that it is sacred. But if we look at the native cultures before they became Orthodox, we see that they lived very spiritual lives, connected to nature, to the environment, to each other, and to their understanding of God and the Creator. So, they very much see their land as sacred in that way as well. It is something that predates Christianity.

Simon Scionka I would say that Spruce Island is America’s Holy Land in some ways. If you can, go there and experience it—through St. Herman’s prayers and through his holiness, through his ministry and service to God, we really see that it is sacred. But if we look at the native cultures before they became Orthodox, we see that they lived very spiritual lives, connected to nature, to the environment, to each other, and to their understanding of God and the Creator. So, they very much see their land as sacred in that way as well. It is something that predates Christianity.

You go there and you’ll see this magnificent place, the beauty of God’s creation. You encounter the magnificence of the mountains or the vastness of the tundra. You realize that this environment is much bigger than yourself. And you get the sense of being in God, in God’s power, in God’s presence. I think it is tangible there in Alaska. You can experience it that way.

—What did you discover about Alaska, Alaskans, and Orthodoxy while making this film?

—We discovered very much. When we first started making the film, we had a rather loose idea. We really wanted to tell the stories of the early saints, the missionary efforts of St. Herman, of St. Innocent, and of St. Yakov, who was the first native to be ordained, with his missionary efforts to a different tribal culture in Alaska.

Spruce Island But then we spent some time with people who are Orthodox today, and we found many things. What is interesting is that there is a real legacy, particularly among the Yupik people. They have remained strong in Orthodoxy to this day, through the influence of the saints that evangelized these areas. It is a really beautiful example of living the Orthodox faith. They live very simply in these rural territories; they are connected to nature and their environment, connected to one another within the community. They hunt and fish and take care of their elders and their neighbors, and live their Orthodox life in this humble, simple, even somewhat hidden, but very beautiful way.

Spruce Island But then we spent some time with people who are Orthodox today, and we found many things. What is interesting is that there is a real legacy, particularly among the Yupik people. They have remained strong in Orthodoxy to this day, through the influence of the saints that evangelized these areas. It is a really beautiful example of living the Orthodox faith. They live very simply in these rural territories; they are connected to nature and their environment, connected to one another within the community. They hunt and fish and take care of their elders and their neighbors, and live their Orthodox life in this humble, simple, even somewhat hidden, but very beautiful way.

I think this discovery had a great impact on me personally, and I hope this comes across in the film. Many of us can watch and say, “Okay, our place is very different, but it is the place where God put us; where we live, and who is around us—family, friends, neighbors, and our church community. How can we really take care of one another, and serve one another, and fulfill Christ's commandment to love one another as He loves us, and to say—how can we do that? Sometimes, we make life more complicated than it needs to be. And we even make our faith more complicated than it needs to be.

I think it was a big discovery for me, how we can be a little less complicated in our faith and just love our neighbor.

—Is Alaska still Russian?

—Is Alaska still Russian… I would perhaps say no. But, of course, it is a remnant, a beautiful remnant of what the Russians brought to Alaska, particularly in bringing Orthodoxy to Alaska. It remains today. You see the churches, the cupolas, the crosses. They look very much like the Russian churches. And the landscape there is very similar to parts of Russia, to be sure—with berries, the tundra, and all that.

We can even draw this parallel—St. Herman lived on Spruce Island but he came from the island of Valaam. There are some similarities in the nature of these two islands—the trees, the rocks. And even inland, in the tundra, some parts of the culture are very similar to the Russian culture, like going into the forests, picking berries, etc. It is like village life in Russia.

But are the Yupik people similar to people in the U.S.? Partly yes, partly no—particularly in the villages. It is village life, especially native village life in Alaska, and it is really quite unique. I have traveled all around the world over the past 25 years; I've been to Africa, South America, and other areas. But it was very interesting to be in Alaska. In one sense, I was in the United States of America, and in another sense, I felt like I was in a totally different country—even the way Yupik village life works, the way people communicate, their culture. They just operate in a very unique way.

I found it very beautiful and inspiring, and I really enjoyed my time with them.

—When we talk about Alaska, we usually think of St. Herman and St. Innocent. Did you feel their presence? How did you communicate with them while making the film, and how now that the job is already done?

-Sure. St. Innocent and St. Herman are both great saints from Russia, who for us here in the U.S. are part of our grouping, if you will, of Orthodox saints of North America. They are a large part of how Orthodoxy came to the land of North America.

Did I feel their presence up in Alaska? Absolutely! In particular I would say that the strongest is that of St. Herman. I was able to venerate his relics, which are in Kodiak. I have been to Spruce Island, and spent time in that land where he lived his monastic life of prayer. You really feel his presence there on the island; it is very tangible, very moving and beautiful.

Silas Karbo on Spruce Island During the filmmaking process I was back in Russia with my family, because my wife is from Kostroma. We went there to visit her family and drove from Moscow to Kostroma through Sergiev Posad. We always stop there at the [Holy Trinity-St. Sergius] Lavra for a couple of days to visit and pray there. I was able to make some connections. We usually venerate St. Innocent, whose relics are there. I also got permission to film briefly there. So, yes, St. Innocent, through his prayers, is a very large part of our project.

Silas Karbo on Spruce Island During the filmmaking process I was back in Russia with my family, because my wife is from Kostroma. We went there to visit her family and drove from Moscow to Kostroma through Sergiev Posad. We always stop there at the [Holy Trinity-St. Sergius] Lavra for a couple of days to visit and pray there. I was able to make some connections. We usually venerate St. Innocent, whose relics are there. I also got permission to film briefly there. So, yes, St. Innocent, through his prayers, is a very large part of our project.

It was amazing to be able to visit his relics and pray to him during the filming process, and to continue to do so afterwards.

—One priest in your film said that St. Herman and St. Innocent maintained the Alaskan context, which is different depending on the region—Yupik or Aleut. What different contexts did you see?

—There are more saints in Alaska, but we mostly talk about three of them—St. Herman, St. Innocent, and St. Yakov. St. Yakov was of Russian and Aleut descent; he went to Russia to study and then came back. But he was sent by St. Innocent to the Yupik people, who were a different group of people, whom he did not know. He evangelized them. However, none of these saints were there to simply impose on the local people the Russian way of doing things, but rather to teach them the Orthodox way of doing things. These native Alaskans embraced Russian Orthodoxy. But they also had to do and learn things, like their own language and culture.

It was very interesting to see things that we do not show in our film. We were able to see early prayer books. No one forced them to learn the Church Slavonic language in order to read all the prayers. The Church said, “Okay, let us translate this into the local language, so that they would have Cyrillic lettering.” But it was their language written in Cyrillic, and they learned how to read the prayers. Even today they still sing in their native language, which is quite beautiful to hear. We included some troparia and a few other moments in the film when the prayers are sung in the local Yupik language.

Yes, just seeing that was quite beautiful.

—Can you explain why the preaching of St. Herman, St. Innocent, and other ascetics in Alaska was so special? What was the difference between them and the preaching of other people in other places?

—I am not a historian, but this is a part of what I learned through some of the reading and from the people I spoke with in Alaska, particularly Fr. Michael Oleksa. His books really delve into all of this quite deeply, and I highly recommend them because they have all the stories of what these missionaries did.

But to summarize it, they were very patient with these people. They listened to stories from the native cultures and traditions in order to get to know the people, to get to know the language, to build relationships, to help them and to serve them in particular ways. Even before they really began preaching and converting people to Orthodoxy, they wanted to learn and respect who these people are, to understand them. And then they would also find ways to make connections with the Christian story, to tell the story of Christ to these people who had never heard about Jesus Christ before, and tell it to them in a way that made sense and was tangible and connected.

While there were things that I am sure had to change within the culture, there were areas where they had some common ground on which they could build a foundation. They could show how Orthodox Christianity could be the fulfillment of what they believed and the completion of those things—the truth of Christ, Who Christ is, and that He has always been there. It helped them make a connection, to see that yes, this is true because of Christ.

They were able to do that in a way that was very respectful of the culture and honoring their traditions. But they also brought them into the fullness of faith in Christ, and the fullness of the Orthodox faith.

—How did it happen that the seeds sown by St. Herman and St. Innocent sprang up so abundantly and continue to bear fruits even now, more than two centuries later? Alaska is probably unique in this regard, because we rarely see this in other places.

The grave of Matushka Olga in Kwethluk —Yes, I would agree that Alaska is unique in this regard. We talk in our film about Matushka Olga Michael, who was the wife of a priest. She had, I think, nine children, and worked as a midwife in her village. She lived a very saintly, holy life, a life of prayer, of real physical struggle in that environment, and in real love for people, helping women.

The grave of Matushka Olga in Kwethluk —Yes, I would agree that Alaska is unique in this regard. We talk in our film about Matushka Olga Michael, who was the wife of a priest. She had, I think, nine children, and worked as a midwife in her village. She lived a very saintly, holy life, a life of prayer, of real physical struggle in that environment, and in real love for people, helping women.

The Orthodox Church in America (OCA) is now officially taking steps to canonize her as St. Olga of Alaska, from the tiny village of Kwethluk.

You see the sort of legacy, if you will, of what St. Herman and St. Innocent began and planted, and which continues to grow to this day, even continuing to produce saints. It is really quite beautiful.

How is it happening? I do not know. It is just the work of the Holy Spirit. But I think that what the saints tried to do, to bring Orthodoxy, was very natural, because the Yupik people particularly embraced Orthodoxy. It truly became a part of who they are.

It is interesting—I live in Colorado, I have friends there and some of them Orthodox, some not. I say to them, “I am going to Alaska because there are native Alaskan Orthodox people in these small villages.” And people say, “What? We have never heard that!” They have no idea about Orthodox communities there, and these communities are very thankful and grateful for the work of St. Herman and St. Innocent, who brought Orthodoxy to Alaska.

—You just mentioned Blessed Olga, who was glorified by the OCA several months ago. She became the first canonized woman in North America and the first from the Yupik tribe. What did you discover about her during your work?

—We traveled to Kwethluk, which is a rather remote village. To get there you have to take a boat up the river in the summer time, or in the winter you can drive a pickup truck down the river, which is pretty amazing. It was a wild experience. I have never experienced that before.

She lived and served in a very simple, humble, and beautiful way. As some of the people in our film said, she worked hard, she went to church, she sang prayers. She sang Christmas carols and showed the beauty of life in Christ.

She always had extra children in her house. If anyone needed clothing, she clothed them. If anyone needed food, she fed them. When anyone had hardships, struggles, faced challenges, or had been abused, she would come for them, make a tea, sit with them, and listen to their stories, and through those encounters she brought comfort and peace to other people’s lives. You can just see this in her life.

This is again a certain takeaway for me: How can we, as Orthodox Christians who live wherever we live—in the U.S., in big cities, in Moscow, with busy lives—just live with our Orthodox faith in our work, in our studies, in our family life.

Fr. Andrew on Spruce Island I think St. Olga’s life is a very beautiful example, which lets us think, “Okay, I can do that. I can love the people that God has put before me. And that is the challenge we all have. What does it mean to become a saint? Can we go to church? Can we read our prayers? Can we sing Christmas carols? Can we love our neighbor?” We can really see this in the life of Matiushka Olga.

Fr. Andrew on Spruce Island I think St. Olga’s life is a very beautiful example, which lets us think, “Okay, I can do that. I can love the people that God has put before me. And that is the challenge we all have. What does it mean to become a saint? Can we go to church? Can we read our prayers? Can we sing Christmas carols? Can we love our neighbor?” We can really see this in the life of Matiushka Olga.

—It was very interesting for me to hear in your film familiar Russian Orthodox prayers in native Alaskan languages.

—Yes, it is fascinating and beautiful. That was important for us. One of the things we wanted to do in the film was to allow people to hear the native language. You can even recognize many of the tones, but all the words are in the Yupik language; and it was very nice to hear these prayers.

St. Olga of Alaska You said in the film that when Russia sold Alaska to the U.S. in 1867, it could have been expected that the local people would throw away everything related to Russia. But in fact, they even became more Russian. How can we explain this?

St. Olga of Alaska You said in the film that when Russia sold Alaska to the U.S. in 1867, it could have been expected that the local people would throw away everything related to Russia. But in fact, they even became more Russian. How can we explain this?

—This is the point Fr. Michael tries to make in the film. “Look, sometimes your broader view of history is: ”Well, the Russian people were just over there exploiting the natives for labor and forced them to convert to Orthodoxy.” Fr. Michael argues, “No, that is not what happened.” Because if that was what happened, the natives would have burned down the churches and gotten rid of Orthodoxy.

No, something else was clearly going on, because Orthodox Christianity resonated with who they were, and they truly became Orthodox Christians. So, they remained Orthodox Christians, and that is because Orthodox Christianity was really connected with who they inherently were as a people. For them it made sense, they remained Orthodox. And in fact, Orthodoxy even continued to grow for a number of years after the Russians left.

—It was nice to see elderly people who said that they were Russian Orthodox, and whose parents and grandparents were also Russian Orthodox. That means that Orthodoxy has been passed down from generation to generation for centuries. How would you explain this phenomenon?

—When they became Orthodox it was real for them. It was not forced, it made sense to them. As a people, they pass it down from generation to generation and continue to do so now.

Do they have struggles? Of course they do. We are all struggling; in every culture you go through these waves. Sometimes it is hard to pass down these things from generation to generation. And obviously, those in Alaska are struggling as well, like we are in other parts of the country or in the world.

To me, one of the important things to show in this film was the idea of remembering our elders, honoring our elders, and honoring those traditions of learning who we are and where we came from, and striving to keep those traditions alive as we pass them from generation to generation.

So you see it up there, and it has been going on. And God willing, such events as the glorification of Matushka Olga as a saint will hopefully be a real encouragement to the next generation of Alaskan natives and to all of us, who can look to her as an example, and keep the faith alive.

We just have to look at our elders, our saints, who have come before us and say, “What can I do to be like them?

Fr. Ishmael and Herman Davis, in native costume

Fr. Ishmael and Herman Davis, in native costume

—Do you think we should hold these people up as an example for ourselves?

—Very much so, yes. I think that what you can see is an example of how we can live. Sometimes I like to refer to a kind of a hidden life. People just live humble, simple lives in the glory of God, and I think that today this could be a real example to us of how we can live our faith.

—You made your film in English. Are you going to translate it into Russian?

—Yes. We have translations with subtitles in Russian, Greek, Romanian and Serbian. We are finishing subtitles in those languages because we would love to release the film in other countries as well. Right now, the Russian subtitles are being edited and finalized. As a filmmaker, I would like to try to get the film into a couple of Russian film festivals, and then we can have a wider release of it in Russian and other languages.