At any large church bookstore or site, you can purchase the Lives of the Saints—collections of stories about Christians who were canonized by the Church throughout different periods. The most comprehensive collections of these lives fill dozens of volumes, while the more concise ones can easily fit into a lady’s handbag. However, regardless of the size, all these editions share a common source: Russian Orthodox readers know about saints who lived before the Renaissance thanks to one man—Dimitry (Tuptalo), Metropolitan of Rostov. It is his texts that form the foundation of most modern collections of saints’ lives.

At any large church bookstore or site, you can purchase the Lives of the Saints—collections of stories about Christians who were canonized by the Church throughout different periods. The most comprehensive collections of these lives fill dozens of volumes, while the more concise ones can easily fit into a lady’s handbag. However, regardless of the size, all these editions share a common source: Russian Orthodox readers know about saints who lived before the Renaissance thanks to one man—Dimitry (Tuptalo), Metropolitan of Rostov. It is his texts that form the foundation of most modern collections of saints’ lives.

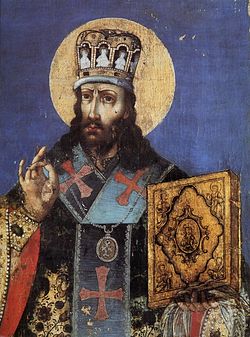

To be fair, St. Dimitry was not only the greatest Russian systematizer of the lives of the saints. He also entered history as a scholar, theologian, polemicist, preacher, writer, and even as a playwright—two of his religious plays, written in honor of the Nativity of Christ and the Dormition of the Theotokos, have survived to this day. In many ways, the archpastor of Rostov was a unique personality and deserves careful attention, just as does the complex era in which he lived and worked.

“Thus saith the Lord, Stand ye in the ways, and see, and ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls. But they said, We will not walk therein.” (Jeremiah 6:16, KJV).

The future bishop was born in December 1651 to the Cossack centurion Savva Tuptalo and his wife Maria. At his baptism, the child was named Daniel. The pious family first lived near Kiev, but when the boy grew older, his parents moved to the capital itself. Daniel’s upbringing was primarily overseen by Maria, as Savva had little time to stay home for long periods. His mother sowed the seed of faith in Daniel’s heart, while his father provided an example of a capable and wise administrator. The young Tuptalo’s talents developed to their full extent when he began to serve the Church. But those around him mostly noticed the boy’s sharp mind—curious, keen, and lively. When Daniel turned eleven, as the son of a distinguished Cossack he was sent to study at the Kiev Brotherhood College, the most prestigious educational institution not only in Ukraine but throughout all Rus’.

Despite oppression from the Polish nobility, education in Ukraine was significantly more advanced than in the neighboring Russian lands. There were several reasons for this. The most influential factor was that since 1596, two Orthodox Churches had coexisted in the territories under the Polish crown. One of these—the Uniate Church—externally retained the Orthodox form of worship but was canonically subordinated to the Roman See and served as a means of converting Ukrainians to Catholicism. The other, larger and more representative, remained loyal to Orthodoxy, and stood in opposition to Rome, for which it was declared illegal by the authorities. The first Church enjoyed the full support of the state, while the second for a time lacked even a sufficient number of bishops.

The Orthodox rose up against their persecutors more than once, sparking reactions that further fueled the enmity between Christians. At the same time, there emerged a realization that Catholic expansion could also be resisted peacefully—through pamphlets, petitions, lawsuits, and books. But for this, an entire army of educated people was needed, capable of engaging in dialogue with their opponents on an equal footing. By the second quarter of the seventeenth century, a powerful system of educational institutions had developed, drawing on the experience of Catholic universities and directing efforts toward defending the rights of the Orthodox population and fostering the local culture of what is now Ukraine. This system managed to function successfully until the end of the eighteenth century, when the center of education in Rus’ finally shifted to Moscow and St. Petersburg. The influence of the Western Rus’ Kiev school was so strong in many aspects of life in Eastern Rus’, that only the reign of Catherine the Great brought this phenomenon to an end.

In the seventeenth century, Ukraine produced a whole constellation of outstanding thinkers and scholars who left behind a rich legacy, and raised equally talented students. The education in the Western Rus’ schools differed significantly from the methods in distant, cold Muscovy. In Moscow, education was more focused on rote learning and served practical purposes—teaching a young person to read, write, count, build, and manage a household. But entering a college in Kiev or Vilnius offered much more than just practical knowledge. Here, a holistic worldview was instilled, and students were taught to think critically. Not only theological but also secular subjects were taught. It was into such an environment that young Daniel Tuptalo was immersed when he crossed the threshold of the Brotherhood School.

Under the guidance of Rector Ioannikiy Golyatovsky—an outstanding preacher and orator—the future saint developed a remarkable gift for oratory. He soon became one of the best students. At the same time, the spiritual fathers began to notice that Daniel was inclined towards solitude and prayer. A few years later, his desire for monasticism played a decisive role in his life. In 1668, with the blessing of his parents, the young man became a novice at the Kiev St. Cyril Monastery, and soon he took monastic vows under the name Dimitry. A year later, he was elevated to the rank of hierodeacon. While fulfilling the usual monastic obediences, the young ascetic engaged in spiritual and literary labors and continued his education. By 1675, Dimitry, now a hieromonk, was one of the leading preachers, known far beyond the borders of Kiev and Chernigov.

Like many former students of the bursa (seminary), Father Dimitry was not of noble birth. But what is most remarkable is that, while a prestigious education often led young men to pride and arrogance, Tuptalo was completely devoid of these qualities. When preaching before the faithful, he did not stand as a pompous orator full of lofty rhetoric, but as a simple monk, who with lively and vivid language revealed the essence of various spiritual problems. Neither was there any haughtiness in Father Dimitry’s personal interactions—he treated everyone with equal respect. Moreover, the lower the social status, the more love the young priest showed. And the saint carried this gift of love for others throughout his entire life.

The fame of the learned and humble monk spread quickly, and as soon as he became a priest, Father Dimitry received one invitation after another from various monasteries, asking him to become their abbot. At first, he refused, because he desired the quiet life of asceticism in his cell, dedicating himself to writing. But seeing that more and more invitations were coming, and recognizing in this the will of God, Hieromonk Dimitry eventually agreed to take up the cross of abbotship.

Within a few years, the preacher traveled to all corners of the Orthodox Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. By that time, Ukraine had already begun to recover from the terrible wars with the Poles and decades of Catholic expansion, but even now, much work awaited the young abbot. Simple believers thirsted for the word of God, monasteries needed wise administration, and spiritual education required development. And Father Dimitry humbly did what he had to do—he preached, organized monastic life, taught in schools, and established a system of enlightenment. But he had another goal: to collect as many manuscripts and books as possible. From an early age he loved reading the lives of the saints from previous centuries and was inspired by their examples of holiness. Over time, this love for studying biographies grew into a firm desire to compile into one volume all the surviving information about the Christians commemorated by the Church each day. It took the saint twenty long years to achieve this goal. In 1684, he was blessed for this endeavor by Metropolitan Barlaam (Yasinsky) of Kiev, and in 1705, the final volume was printed. No one before had ever dared to undertake such a monumental task. The full weight of Dimitry of Rostov’s accomplishment becomes clear when considering that he did nearly all of the writing himself. As he later admitted, it would have been impossible for him to complete this work without the help of God and the saints about whom he wrote.

In 1689, another significant event occurred in the priest’s life—while on a business visit at the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery, he met Tsar Peter I [the Great] of Moscow. The young reformer saw in the Little Russian monk an active man, quite different from the residents of Eastern Rus’, who were resistant to changes and innovations. The tsar took note of the Kiev preacher, and ten years later, a messenger from Moscow arrived at the Kiev Caves Monastery, where Father Dimitry was working on the Lives of the Saints. He brought a decree from Tsar Peter appointing Hieromonk Dimitry to the bishopric of Tobolsk. Father Dimitry could not oppose the Russian sovereign, and in 1701, he was consecrated a bishop in Moscow. However, Dimitry did not remain in Siberia for long—he longed for his homeland, his health was poor, and he could not continue his beloved work in the remote wilderness. The metropolitan petitioned Peter I to transfer him, and in 1702, the tsar appointed Dimitry as the Metropolitan of Rostov [in southern Russia].

In his new position, the saint faced a situation unlike anything he had encountered even in the lands ravaged by the Uniates. The morals of the people of Rostov were in a state of extreme neglect. Even the children of priests, for the most part, never took Communion. The bishop began by imposing stricter requirements on the moral conduct of the clergy. It was in Rostov that he wrote his bitter words describing the negligent priests: Ye seek Jesus, not because ye saw the miracles, but because ye did eat of the loaves, and were filled (John 6:26).

Seeking to change the situation, the bishop opened a school at his residence to train pastors, and personally oversaw their education and upbringing. The school accepted not only sons of priests but also any talented boys., The metropolitan fought no less actively against superstitions and the Old Believer schism, clearly and rationally presenting his position. Gentle and meek, the saint taught everyone prayer, fasting, almsgiving, compassion, and mercy. And he taught not just with words, but by personal example.

However, the saint’s health was weakened by years of travel, lack of sleep, and mental strain. He passed away on November 10, 1709. Two days before his death, the bishop celebrated the liturgy, though he no longer gave sermons. Before his death, he had a long conversation with his scribe, Savva Yakovlev, telling him about his childhood, reminiscing about his native Ukraine, his parents, friends, and mentors who had given him such profound spiritual experience. At the end of the conversation, his voice grew weak. The bishop blessed the scribe and bowed deeply to him.

“Why do you bow to me, Your Grace?” the scribe exclaimed in embarrassment, to which the saint gently replied:

“I thank you, my child!” And on the bishop’s face was a pure, childlike smile.

The scribe left in tears. The metropolitan locked the door, and they could hear him praying. That is how he was found in the morning—on his knees before the icons. St. Dimitry was fifty-eight years old at the time. He was buried in the cathedral of the Rostov Yakovlevsky Monastery, and on October 4, 1752, during repair work, it was discovered that the saint’s remains were incorrupt. Metropolitan Dimitry was canonized in 1757.