On May 25/June 7, the Church commemorates Archbishop Innocent (Borisov) of Kherson.

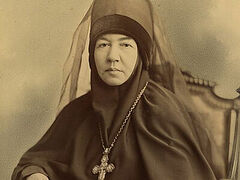

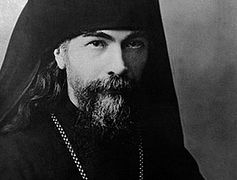

St. Innocent of Kherson and Tauride. Lithograph, 1857 The future saint was born in 1800 in the Orel Governorate in a poor peasant family. He was named John. He grew up in a pious environment, knew the Psalter and Horologion by heart, and became literate at an early age. He graduated from the Orel Theological Seminary, after which he was sent to the Kiev Theological Academy. He was a perceptive young man, possessed of a lively, receptive mind, and extensively deepened his education on his own, taking notes on books he read. During his studies, he manifested a gift of the word, which he put to good use, later becoming a luminary of theological thought and homiletics.

St. Innocent of Kherson and Tauride. Lithograph, 1857 The future saint was born in 1800 in the Orel Governorate in a poor peasant family. He was named John. He grew up in a pious environment, knew the Psalter and Horologion by heart, and became literate at an early age. He graduated from the Orel Theological Seminary, after which he was sent to the Kiev Theological Academy. He was a perceptive young man, possessed of a lively, receptive mind, and extensively deepened his education on his own, taking notes on books he read. During his studies, he manifested a gift of the word, which he put to good use, later becoming a luminary of theological thought and homiletics.

After graduating from the Academy, John was sent to the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary as an inspector and professor of Church history and Greek. Then he became the rector of the St. Alexander Nevsky Theological School at the St. Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

In 1823, he received the monastic tonsure with the name Innocent and was ordained a priest. In St. Petersburg, he became quite famous for the homilies he gave in the Lavra and the Kazan Cathedral. According to the testimony of his contemporaries, Fr. Innocent was characterized by a “rare combination of clarity and simplicity of word, a musical cadence of speech, and artistic vividness of expression.”1 They started publishing his homilies in the St. Petersburg journal, Christian Reading.

Hieromonk Innocent was elevated to the rank of archimandrite and earned a doctorate in theology. As the theologian and exegete Alexander Lopukhin wrote of him:

The very subjects that he taught—Fundamental and Apologetic Theology—gave particular scope to his thought, and the young professor was able to fully reveal the brilliant aspects of his rare talent and extensive education. Clarity and often originality of perspective on the most important questions of scholarship, quickness and penetration of mind, invincible dialectics, and intimate familiarity with the contemporary state not only of theology but also of philosophy in the West—such were the distinguishing features of Archimandrite Innocent’s teaching... The St. Petersburg Academy had the good fortune for six years to be nourished by the fruits of Fr. Innocent’s brilliant mind and most noble heart.2

In 1830, he was appointed rector and professor of the Kiev Theological Academy. In this position, the young rector and professor introduced some changes to the Academy’s educational process. Under him, all lectures, previously given in Latin began to be taught in Russian. Archimandrite Innocent also introduced new subjects, encouraging the students to study more broadly, not focusing solely on the theological sciences. At the same time, he taught the students fundamental and dogmatic theology, leaving them amazed and delighted. One day he told his pupils: “I’m surprised you don’t value your time and don’t do much; during Cheesefare Week and the first week of Great Lent I wrote about eighty pages!” One of his students said of him: “He was a genius, in the truest sense: a high, bright, penetrating mind; a rich, inexhaustible imagination; a vivid and extensive memory; a quick and easy wit; subtle, proper taste; the gift of creativity, ingenuity, and originality; the most perfect gift of speech—all this was wonderfully and harmoniously combined in him.”3

In Kiev, Fr. Innocent proved himself to be, first of all, a talented preacher, theologian, and versatile encyclopedist. Under him, the journal “Sunday Reading,” originally founded for Academy students, spread throughout the villages.

In 1836, Archimandrite Innocent was elevated to the episcopacy, and in 1847, he was appointed a member of the Holy Synod. In 1848, he became Archbishop of Kherson and Tauride. During these years, collections of his sermons were published, as well as his hymnographic works in the form of various akathists. In the diocese entrusted to him, the Holy Hierarch conceived the idea of restoring Chersonesos as the site of the Baptism of Prince St. Vladimir. In 1850, a cenobitic monastery was founded there, which later became the male Chersonesos-Prince Vladimir Monastery. Additionally, other monasteries of the peninsula were restored and several sketes were opened under St. Innocent. The archpastor intended to create a semblance of Mt. Athos in Crimea, but it wasn’t meant to be.

The saint was also distinguished by his poetic nature. One of the Archbishop’s contemporaries testified about an evening spent in his company:

It was getting dark. His Eminence suddenly asked me: “Do you like to watch a fire burn?”

“I do.”

“I do too. Tell them to bring some firewood and make a fire here, by the water [there was a small lake in front of the house], as big as possible. We’ll watch it all burn and listen to the nightingales sing.”

The Holy Hierarch’s poetic disposition, high education, and living faith were directly reflected in his preaching as well. In particular, in his Homily on the Feast of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, he asked:

The Holy Hierarch’s poetic disposition, high education, and living faith were directly reflected in his preaching as well. In particular, in his Homily on the Feast of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, he asked:

Has our heart been transfigured by the Holy Spirit? What is the foundation of our activity—love for God, poured out in our heart by the Holy Spirit, or love for the world, flowing from the bottomless pit (Rev. 9:2)? Where is the model that we strive to conform our lives to—in the Gospel, or at the crossroads of the world; amongst the hosts of the righteous written in Heaven (Heb. 12:23), or in a crowd of sinners like us? Where are we more eagerly drawn: to houses of mourning or houses of joy; where they gather in the name of Jesus Christ, or where the world reigns with its lusts? Do we fulfill our duties as befits a servant of Christ, in singleness of heart, as unto Christ, or with eyeservice, as menpleasers (Eph. 6:5–6). Have those whom duty or circumstance has placed in dependence upon us grown weary of sighing from our hard-heartedness and pride? Do tears flow abundantly when we turn our gaze upon our sinful life? Do we strive by good measures to return to the path of salvation those who have been led astray from it by our scandalous life?

And further he instructed:

Do not quench the Spirit: Flee from every thought of sin; distance yourselves from fellowship with depraved people, turn your gaze from all spectacles where the lust of the eyes and the pride of life may shake even the firmest conscience... Do not count your good deeds, do not take too much pleasure in those virtues which grace has helped you acquire; firmly remember that we are unprofitable servants who have done only what we were commanded to do... The Apostle cries out to all: Be filled with the Spirit! (Eph. 5:18). Arouse yourself to do good and do it as much as possible.

During the Crimean War, St. Innocent set a personal example of what he fervently preached from the ambo. He visited the battlefields, exposing himself to danger, and celebrated the services in the churches of Sevastopol under the whistle of bullets and explosions of artillery. He inspired exhausted soldiers and the wounded in typhoid infirmaries with his archpastoral word.

The Holy Hierarch’s diocese also included Odessa. In April 1854, the city was besieged. Right during the hierarchical services, one of the Odessa churches was shaken by enemy bombardment. For all this, Vladyka Innocent maintained his presence of mind, encouraging his flock with his firm preaching.

The glorification of the Kaspersky Icon is also associated with the name of St. Innocent. After the icon itself was found, by request of the faithful, it was transferred to Odessa in a procession. For nearly two years, the archpastor of Kherson served penitential molebens before the icon with an akathist that he wrote himself. The enemy retreated from the city, and the wonderworking Kaspersky Icon became the patron of Odessa and the entire Black Sea region.

Selfless archpastoral labors undermined the Holy Hierarch’s health. On May 25, 1857, on the feast of the Life-giving Trinity, he suddenly reposed. As one of his biographers wrote:

On the Memorial Saturday before Pentecost, St. Innocent asked to serve a panikhida and read the canon to the Holy Trinity. It was five o’clock in the morning, it was getting light, and Vladyka went over to the window and said: “Lord, what a day!” And moments later, he reposed in the arms of two of his cell attendants, bowed in prayer.4

On July 18, 1997, his fragrant relics were uncovered and translated to the Holy Dormition Church of the men’s monastery in Odessa.

The twentieth-century Church historian Metropolitan Manuel (Lemeshevsky) wrote about Archbishop Innocent:

It wasn’t scholarship that was his true calling, but the art of the human word. He was not only an excellent connoisseur but also a brilliant artist of the Russian word. A bright mind, extensive memory, creative imagination, comprehensive erudition, captivating eloquence, a majestic and dignified appearance—these are the traits by which contemporaries characterized the renowned Innocent.

After his death, one of the Holy Hierarch’s acquaintances, left the following memories of him:

Anyone who visited the rooms of the deceased remembers how many books he had, and seemingly all read at once: in his study, and in the drawing room, and in the bedroom, and in the hall—there were books everywhere. Books on tables, books on chairs, on windowsills, and on shelves. He not only walked and sat with a book, but even fell asleep not just with a book, but on books.

Lopukhin, in turn, commented on the Holy Hierarch of Kherson as follows:

He was a comprehensive scholarly theologian, in many respects ahead of his time; a brilliant preacher—a Russian Chrysostom who captivated men’s hearts, and a self-sacrificing pastor ready to lay down his life for his flock.

Undoubtedly, the word of the “Russian Chrysostom,” the Archbishop of Kherson, can captivate and warm the hearts of our contemporaries. In a homily on Pentecost, we read from him:

He who desires to partake of the grace of the Holy Spirit must necessarily be separated from the earth; he must be detached from all earthly things in soul and heart, begin to set his mind on things above, seek the things that are above, look not at visible goods, which are corruptible, but at invisible ones, which are eternal... In each of us there is a constant, faithful and effective means for attracting the Spirit of God. This is prayer, or the striving of mind, heart, thoughts, and desires toward God. All things have been promised to prayer by the Lord Himself; how much more can we always acquire through it what is necessary, that is, the grace of the Holy Spirit, without which there is not and cannot be anything truly good in us.

On this day, let us pray to St. Innocent with the words of the troparion in his honor:

From thy youth applying thyself to the study of piety and the fear of God, advancing in the grace of Christ, thou didst acquire the gifts of speech and appear as an untiring preacher of salvation, illuminating the souls of the faithful with saving meanings and leading all to amendment of life. Holy Father Innocent, pray to Christ God to grant us forgiveness of sins and great mercy.