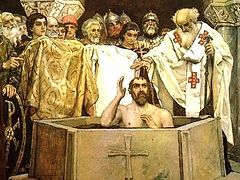

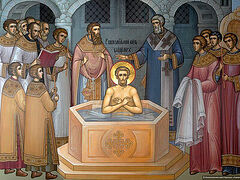

V. Vasnetsov. “Baptism of Rus’,” fragment

V. Vasnetsov. “Baptism of Rus’,” fragment

If a person is fortunate enough to be born into a family where several generations live side by side, then he will most likely be raised by his grandmother. His mother will nurture him at the breast, while his father will furrow his brow if the child does something wrong. But as for telling him where the moon and stars come from, what heroes lived in olden times, why animals don’t talk, and much, much more—that is his grandmother’s job. A grandmother’s love is instinct multiplied by experience; it is sadness and tenderness, born of the delicate contact between age and newborn innocence.

If it weren’t for Pushkin’s nanny, we would not have been able to read the tales of Alexander Sergeyevich. And if it weren’t for Prince Vladimir’s grandmother, he would probably not have been baptized, which means our history would have taken a different course. To her grandmotherly affection, St. Olga added the sign of the cross. Gazing at her grandson, she most likely whispered prayers, and this would have been the first seeds sown in his soul, which produced a rich harvest over time.

Church poetry calls St. Olga the “morning star,” whose appearance on our Fatherland’s horizon heralded the rising of the Bright Sun—holy Prince Vladimir. Vladimir’s grandmother prayed him out, or to be more exact, through her prayers came that powerful turn of the wheel, which changed the course of the great ship. “And the sails did billow, the winds a’ heaved. The juggernaut launched, and the waves it cleaved” (Pushkin).

St. Nikolai (Velimirovic) writes that the vast fields stretching from the Danube to the Pacific Ocean began to be plowed and sown with the Gospel word starting from the Baptism of St. Vladimir. Compared to the enormity of this field, both the Roman and Byzantine Empires appear as small islands.

Bled pale by religious wars and having lost faith in itself and in the truths it had long and fervently confessed, Europe saved itself in America. The white man with a Bible in his hand found a new homeland across the ocean and began settling there, striving to turn it into an earthly paradise. Byzantium saved itself in Rus’—or rather, not itself. Mohamed’s sword had destroyed its might. Byzantium was able just in time to hide its treasure, its pride and joy, for the sake of which it lived—Orthodoxy. It had brought it to Rus’. “For Orthodoxy, Scythia meant just as much as America for Western Christianity—even more,” writes St. Nikolai.

Rus' received the Christian faith ready-made—as a faceted, polished diamond set in the precious mounting of the Byzantine rite. It is remarkable that the Lord entrusted this treasure to a people so inexperienced in earthly wisdom and science, a people with no written history or even an alphabet. I sent you to reap that whereon ye bestowed no labour: other men laboured, and ye are entered into their labours (Jn. Here’s a proofread version of the sentence:4:38)—these words of Christ can be appropriately applied to this new Christian nation—Rus’.

P. Ryzhenko. “Baptism of St. Vladimir’s army in Chersonese.” A fragment from a diorama

P. Ryzhenko. “Baptism of St. Vladimir’s army in Chersonese.” A fragment from a diorama

There was no Jericho in the new lands for the Gospel trumpet to destroy. There was nothing to destroy but wooden idols. No pyramids, no pagodas, no marble sculptures, no philosophies, no theater, no lofty poetry—nothing resembling Rome or Greece, Egypt or Babylon with their extravagant and tempting paganism. It was all primitive, all close to nature. But sin itself was unbridled, like the tempestuous elements.

When God wants to incarnate His plans aimed at eternity, He searches for people on earth who are capable of assisting Him. His choice is not fleeting. If people, instead of God, were to make this choice, they would inevitably make mistakes. After all, unlike God, they do not know the secrets of human hearts. It is like Samuel, who peered into eternity, was mistaken as to which of the sons of Jesse should be anointed king over Israel (cf. 1 Kings 16:6–12, Septuagint). In the case of Rus’, the Lord also made His choice, which would have been impossible from an ordinary man’s point of view. He chose St. Vladimir.

Love of earthly pleasures, vices, and superstitions covered Vladimir from head to toe. But his interior, like the inner rings of a tree, was healthy. He was to be transformed from a caterpillar into a butterfly, and through the power of living example, call all the people under his authority to follow him. God saw that the prince’s soul was both courageous and truthful. He sinned; he did not know the truth, but having come to know it, he was capable of abandoning sin.

He, like us, was surrounded and beckoned by Judaism, Islam, Catholicism, and Orthodoxy in matters of faith and religion. The prince’s choice had to be been made without sufficient knowledge, religious or historical. He had to be guided in his decision by his natural intelligence, a statesman's common sense, and intuition.

God takes special care for princes and kings. Pharoah during Abraham’s time and Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel’s saw prophetic dreams or were brought to reason in special ways by God. This is because the fate of the world and the lives of millions of people depended upon their decisions. This was true in full measure for Vladimir, even when he was still a pagan and stood with his people at the crossroads of history.

S. Isayev. “The choice of faith by Vladimir the Baptizer”

S. Isayev. “The choice of faith by Vladimir the Baptizer”

His argument for refusing to accept any faith other than the Orthodox faith may sound naïve. But this is the kind of situation about which the Romans used to say, “The pretext is trivial, but the cause is great.” He declined the Catholics and Muslims for reasons that were by no means a matter of principle. He only asked a question of the Jews—at the same time, a great counterargument: “If your faith is the best, then where is your land, where is your state, and why did God disperse you across the face of the earth?”. But I repeat, his rejection of those faiths was not at all based upon the words spoken by the Islamic, Jewish, and Western missionaries. This was a matter of God’s Providence, for which Vladimir was the best instrument.

Out of what was, at that point in time, a unified Christianity (it was a half century before the Great Schism), the prince chose the Eastern variation. If the Latin services did not move him, then the Byzantine Liturgy, on the contrary, made Vladimir’s merchants forget where they were—whether in heaven or on earth. The bright image of St. Olga came to the emissaries’ minds in the most compelling way. Moved by the divine services, they said that the most-wise Olga would not have chosen Orthodoxy if it were not the best faith. The preaching of the Greek missionary, the icon of the Last Judgment, and the explanation of the image topped it all off for the prince. From that time until today, we, his latter-day grandchildren, honor icons, cannot conceive of faith without solemn and majestic divine services, and of course, we love our grandmothers who bring us up.

There is another element in the Baptism of Rus’ by Vladimir that begs other questions. The prince baptized the people by force of will, without any previous catechization. “Whoever does not come to the Dniepr is no friend of mine,” said Vladimir, and after these words it was hard to find anyone who voluntarily wished to become the prince’s enemy. In Leskov’s tale, “On the Edge of the Earth,” one of the main protagonists says that “Vladimir was in a hurry, and the Greeks were cunning.” That is, the Greeks hurriedly baptized the people without having taught them the basics of the faith. There is some truth to these words, and we shouldn’t ignore it. Left in our language from those times is the word “kurolesit’.” It means, “to do something perplexing.” But it came from the Greek, “Kyrie eleison,” that is, “Lord have mercy.” For a long time, the services were performed by the Greek clergy who came to Rus’, who served in a language unknown to the Slavs, and the newly baptized would go to the churches where the Greeks “kurolessed.”

But it is also true that Rus’ loved its new faith. Anything glued to the exterior will always come unglued after a short time, but whatever penetrates within will remain and go deeper. That is just how the seed sown by Vladimir deepened in the Russian people, and soon from the bowels of a newly baptized nation a mighty spirit would be born—true monk and ascetics. That wondrous life of Palestine and Egypt, which in the fifth and sixth centuries amazed Heaven, was repeated in the hills of Kiev in the eleventh century. Recluses and hesychasts, unmercinaries and men of prayer, whom demons feared and the dead obeyed, could never have come about were it not for the Rusichi’s1 total and complete dedication to Christ and the Gospel. It is enough to visit the Kiev Cave Lavra for a day and quickly familiarize yourself with its history to understand that Vladimir did not rush, and he made no mistake in his choice of faith.

Yes, of course it is better to first learn the faith, and only then be baptized. When we baptize infants we truly and actually unite them with Jesus Christ. Children do not understand this, although the Sacrament is performed in full measure. After that, the child has to be taught everything so that the gift of faith might be assimilated and loved. If the adults do not do this, reality risks becoming such a jumble that it will be difficult to make a clear judgment about it. But if they baptize the child, and then teach him the faith and bring him into the life of the Church, everything will fall into place and the risks are mitigated.

Y. Leonicheva. Prince Yaroslav Thus, Rus’ was baptized as a child, and required teaching and growth in the faith. Under Prince Yaroslav,2 schools and libraries appeared, learned men arrived from Bulgaria with Slavonic books, and clergy arose from the ranks of the native population. The work of Vladimir found its organic and well-grounded continuation. But soon came the Mongols, and the great rise to the heights ended. Book wisdom and living preaching, which once belonged to the realm of natural necessity, gradually became a rare exception. Rus’ occupied a place amongst Christian nations, but it was a particular place. As if awaiting its hour and mission, Rus’ retreated into a long silence, leaving the historical turmoil and the solving of great questions to others.

Y. Leonicheva. Prince Yaroslav Thus, Rus’ was baptized as a child, and required teaching and growth in the faith. Under Prince Yaroslav,2 schools and libraries appeared, learned men arrived from Bulgaria with Slavonic books, and clergy arose from the ranks of the native population. The work of Vladimir found its organic and well-grounded continuation. But soon came the Mongols, and the great rise to the heights ended. Book wisdom and living preaching, which once belonged to the realm of natural necessity, gradually became a rare exception. Rus’ occupied a place amongst Christian nations, but it was a particular place. As if awaiting its hour and mission, Rus’ retreated into a long silence, leaving the historical turmoil and the solving of great questions to others.

Today, armed with knowledge and sensing our responsibility before God and the future, it behooves us to labor on the already sown field, to enter into the labors of those who lived and labored before us. Considering the number of baptisms and conversions, the number of restored and rebuilt churches and monasteries, His Holiness Patriarch Alexiy II justly called our time the “second Baptism of Rus’.” But this time we, the great-grandchildren of St. Vladimir, should do it differently. Building churches is not enough. We need to teach people the faith. In an era of total literacy, illiteracy in matters of the faith takes on a particularly ominous quality. Vladimir made no mistake, but he is waiting for his descendants to continue his work, just as a composer wants his notes to be read, learned, and played with talent.

From the book by Archpriest Andrei Tkachev, Modest Apostleship: Collected Articles