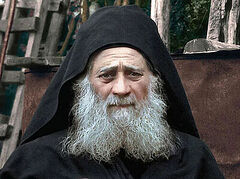

Fr. Visarion of Mastacan

I had been following in the footsteps of the hermits of Neamț for the second day, and it was clear that a complicated path awaited me. My Neamț friend, with whom I had shared my apprehensions, promised to take me to a more communicative hermit who had disciples in the mountains: Fr. Visarion of Mastacan, a village situated near Nechit Monastery.

St. Menas Skete near the village of Mastacan-Borlesti

St. Menas Skete near the village of Mastacan-Borlesti

We turned into the commune of Borlesti, then drove along a broken steep road. I would be surprised to hear that carts could pass here. However, several miles of torment and patience led us to St. Menas Skete, which was under reconstruction after the first wooden church had burned down. From here, we walked for a while along the crest of a hill, driven by the violent wind blowing at our backs. To the left, valleys appeared one after another, from which thin wisps of smoke rose to the sky, as if from giant censers at the ceremony of the blessing of fields.

Fr. Visarion (Baghiu)’s hesycharion was a hut with two rooms and a chapel surrounded by a picket fence nailed pell-mell, as if it had been blown over by the wind. We kept calling the elder at the gate. Two small playful dogs came running. I shouted, knocked, and encouraged the dogs to bark so that the owner could hear us, but they only wagged their tails and snuggled up to me. Apparently, the ascetic was away.

But the gate was open. In the yard, we were greeted by two cats lounging on a beehive in the sun. The dogs snuffled and pranced between our legs, along with the cats that had run up for comfort.

I opened the other gate, into the garden. Behind it, a wizened old man was slowly breaking dry blackberry twigs and ramming them into a bucket. It was Fr. Visarion, dressed like a worker, in black trousers and a thick green plaid shirt, but wearing a scufia.

“Bless us, father,” I said.

The elder did not look up; he was continuing his job with his big and bony hands, as if we were not there. I repeated my greeting, but more loudly and leaning forward so that I could be seen. My companion greeted him too. But the same silence reigned. Then it dawned on me: “The ascetic may have some rule forbidding him to speak!”

“Father, can we talk?”

“Have you some mental anguish?” he asked me when I wasn’t expecting an answer.

“Yes, much,” I answered quickly so that he couldn’t change his mind.

He filled his bucket and beckoned us to sit down on a ramshackle wooden bench by the chapel.

“If you can pray, you are not alone”

Fr. Visarion was eighty-six. He was descended from the peasants who were endowed with land by Voivode Stephen the Great (1457–1504) and lived beyond those hills. Born into a family of devout Christians, he wanted to become a monk from an early age and was tonsured at Nechit Monastery at the age of twenty-two. He was very attached to his monastery, especially since, according to tradition, it was founded in the fourteenth century by a hermit.

Nechita the Hesychast was the first monk who struggled in these parts, and a stream, a valley, and a mountain he lived on as a hermit are named after him. Other hermits gathered around him and put up a small wooden church, laying the foundation of a monastery of hesychasts, which became known as the hesychasterion of Nechita, or Nechita’s Skete. Fr. Visarion is keen on history and can talk about the Romanians’ past for days on end.

Before withdrawing into the desert, he lived in Tarcau, at Darvari Skete, in Bucharest, and at Petru Voda with Fr. Iustin (Parvu), for whom he had great reverence.

I wondered if he had ever wanted to get married, if he had regretted not having tasted the pleasant things of life before becoming a monk.

“It’s not a sin to get married—you can be saved in a family too (laughs),” but he understood his life’s duty in a different way.

It was most difficult in his youth, when the flesh wanted its own way:

“But since you made a promise to Christ, you don’t give the carnal donkey oats, but make it fast and pray, for this is the source of life and salvation.”

Eighty-six years had passed like three days in unceasing efforts for spiritual growth.

He rarely spoke, looking through me. His eyes were blue and sunken, his hair fell over his shoulders, and his gray beard took on a reddish tint in places. He had been a hermit for twenty years. He lived in caves, shelters made of branches, and in the Tarcau Mountains, where there are still hesychasts today.

And in recent years, he returned to his native parts to die here, at home, but still far from the world. He chose the wilderness to purify his soul in the flame of incessant prayer. It is not harder for him to live as a hermit than at a cenobitic monastery. The hardest thing about being a hermit is loneliness. But only for those weak in prayer:

“If you know how to pray, saints and angels are always with you, which means you are not alone. And you’re not afraid of anything. You endure everything with joy, and you don’t really need food—a handful of mushrooms or one potato will be enough for you.”

He loves to live as a hesychast and never tires of thanking God that he can keep going in order to remain a hermit to the end.

“St. Paisius (Velichkovsky) of Neamț, a great elder and organizer of monasticism, said that you should not withdraw into the desert until you have spent twenty years in the brotherhood. Because a person has a lot of ‘sharp corners’, and in a community he ‘polishes’ them by bumping into others (laughs). And St. Theodore the Studite said: ‘Monks in a cenobitic community are saved in thousands, and of those who live an eremitic life—only one in a thousand.’ There should be ‘one mind in all heads and one soul in all bodies,’ as St. Basil the Great instructs. Whereas in eremitic monasticism, every ascetic does whatever he likes. No one guides him or cuts off his will except his own conscience. Well, his father-confessor can guide him, but only if he asks for his advice.”

“I came to love monastic life, and I am happy!”

I asked him what was the most valuable thing he had gained from monastic life.

“Perhaps I’m a little bit less wild than someone who hasn’t lived like this. Knowing God elevates us above the animals. But no one in this world knows God perfectly. And we must know that. And let us take into account that no matter how much we pray and fast, we constantly sin against God. And never dare to think that you are better than others, because that means that the devil has already caught you.”

Hieromonk Nicodim (Grosu)’s grave in the cemetery of Sihastria Monastery

Hieromonk Nicodim (Grosu)’s grave in the cemetery of Sihastria Monastery

Fr. Visarion was a disciple of Fr. Nicodim (Grosu), a former university professor and teacher of classical languages who became a monk and then lived as a hesychast at Tarcau, where he passed away at the venerable age of ninety-three. Fr. Visarion learned from Fr. Nicodim that the humbler you are, the deeper prayer penetrates from your mind into your heart. The former professor told Fr. Visarion that he was fortunate that he was “born” a monk, that from a young age he had learned the monastic rule and was not proud of any worldly successes: neither education, nor a job, nor home, nor a car and didn’t have to torture himself later to get rid of this pride.

Fr. Nicodim’s example was followed by several monks who knew him or had only heard about his holy life. His memory had borne fruits. Thus, there are many hermits at Tarcau today: Fr. Daniel, who was an artist and writer in the world; Fr. Grigorie, Fr. Ioanichie who had labored on Mt. Athos… But it’s not easy to reach them, because they don’t want to be found. They sometimes go down to Tarcau Monastery for the Liturgy, confession and Communion, and disappear again for months.

Tarcau Monastery, 1833, the refuge of Neamț hesychasts

Tarcau Monastery, 1833, the refuge of Neamț hesychasts

Fr. Visarion invited us into his chapel the size of a closet. He had everything to celebrate the Divine Liturgy, but he couldn’t do it on his own. So he just read out the prayers. Here he heard confessions and absolved the sins of his disciples, monks and laypeople. He was sought after like a medicinal herb, and since his move to Mastacan it had been easy to find him. But he was not upset about this, perceiving it as a manifestation of love, which he must reciprocate.

He would have talked to us more, but the rule called him, because that’s why he had become a monk. I asked him to put on his cassock so I could take a picture of him. But he categorically refused:

“The world should not know me, because I buried myself for the world.”

I still managed to sneak a few pictures of him, which makes me feel guilty, even if father forgives me.

The sun, which had risen to its zenith, was beginning to burn. The wind died down. The elder slowly headed for the gate—a sign that it was time for us to go. Along the way, he gave us some more advice on matters of everyday life. Then he closed the gate after us and followed us with his old man’s gaze. A few picket fence rails between us and his holiness separated two whole worlds.

I came back to him with the last question: If he were to be given another life, would he become a monk?

“Yes, I came to love monastic life and I am happy!”

Tarcau Monastery, 1833, the cradle of hesychasts in the Neamț wilderness

Tarcau Monastery, 1833, the cradle of hesychasts in the Neamț wilderness