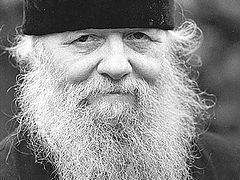

The Blessed Elder, Schema-Archimandrite Sebastian (in the world Stepan Vasilievich Fomin), was born on October 28 / November 10, 1884, in the village of Kosmodemyanovskoye, Oryol Province, into a poor peasant family. His father’s name was Vasily, his mother’s Martha. They had three sons—the eldest, Ilarion (born 1872); the middle son, Roman (born 1877); and the youngest, baptized Stepan in honor of Saint Stephen the Sabbaite, the hymnographer, whose feast day fell on the day of his birth.

The Blessed Elder, Schema-Archimandrite Sebastian (in the world Stepan Vasilievich Fomin), was born on October 28 / November 10, 1884, in the village of Kosmodemyanovskoye, Oryol Province, into a poor peasant family. His father’s name was Vasily, his mother’s Martha. They had three sons—the eldest, Ilarion (born 1872); the middle son, Roman (born 1877); and the youngest, baptized Stepan in honor of Saint Stephen the Sabbaite, the hymnographer, whose feast day fell on the day of his birth.

In 1888, the parents took their children to Optina Monastery to visit Elder Ambrose. Stepan was four years old at the time, but he remembered well that visit and the kind, radiant eyes of the grace-filled elder.

The future Father Sebastian was left an orphan at the age of four, losing his father, and at five lost his mother. His brother Ilarion was then seventeen. To manage the household and support the family, Ilarion married a year after the death of their parents.

Stepan was deeply attached to his middle brother Roman, for his gentle soul and kind heart. But Roman chose the path of monastic life, and in 1892 persuaded Ilarion to take him to Optina Monastery, where he was received as a novice at the Skete of Saint John the Forerunner.

Stepan was a capable student and completed a three-year parish school. The parish priest allowed him to read books. From childhood Stepan was weak in health, so he worked little in the fields, tending instead the cattle as a shepherd.

In the winter months, when there was less peasant labor, Stepan’s greatest joy was to visit his brother in the Optina Skete. These visits had a profound spiritual influence on him, and when he grew older, he began to ask Ilarion to let him go to Optina permanently. But his brother refused, wanting Stepan to help with the farm.

By 1908, the middle brother Roman Fomin, now living in the Optina Skete, was gravely ill and secretly took monastic vows with the name Raphael. On December 16, 1908, in the monastery church dedicated to Saint Mary of Egypt, he was clothed in the mantia by the superior, Father Xenophon.

By this time, Ilarion’s young family was firmly established, and Stepan, resolved to pursue monastic life, came to his brother Father Raphael in the Optina Skete, where, on January 3, 1909, he was accepted as cell-attendant to Elder Joseph.1

Elder Joseph Living under the elder’s guidance, Stepan found in him a great spiritual mentor. Later he often recalled that time:

Elder Joseph Living under the elder’s guidance, Stepan found in him a great spiritual mentor. Later he often recalled that time:

“We (there was one more cell-attendant) lived with the elder as with our own father. We prayed together, ate together, read together, or listened to his teachings.”

Elder Joseph was already in his declining years, and his strength was failing. In April 1911, he fell seriously ill, and on May 9, his soul quietly departed from his much-suffering body.

Stepan’s grief at the elder’s death was profound. But the Lord did not leave him without consolation. Into Father Joseph’s cell moved Elder Nektary, and Stepan remained as his attendant, now under St. Nektary’s spiritual direction.

In 1912, Stepan was tonsured into the riassophore (the first monastic degree).

Elder Nektary had two attendants: the senior, Father Stepan, and the junior, Father Peter (Shvyrev). They were nicknamed “summer” and “winter.” Father Stepan, for his mercy and compassion, was called “summer,” and Father Peter, who was sterner and more austere, was called “winter.” When the crowds waiting in the elder’s humble huts grew weary or discouraged, Elder Nektary would send Father Stepan to comfort them. But when the crowd became noisy or restless, he sent Father Peter, who by his strictness restored order and calm.

Sometimes it happened this way: Elder Nektary usually came out of his cell late in the day—around two or three in the afternoon. The waiting people would often send Father Stefan to tell the elder that they were waiting and that many needed to return home. Father Stefan would go into the elder’s cell, and the elder would at once say, “I am getting ready, dressing, I’m coming,” but still would not come out. And when he finally did, he would turn publicly to Father Stefan and say, “Why have you not told me even once that so many people are waiting for me impatiently?” Then Father Stefan would ask forgiveness and bow at his feet. But sometimes the elder would say to the visitors, “Ask my cell-attendant, Father Stefan—he can advise you better than I can; he is clairvoyant.”

On Great Saturday, April 13, 1913, Father Raphael reposed in the hospital from tuberculosis of the lungs, having been tonsured into the great schema just a day before his death.

In 1917, Father Stefan was tonsured into the mantia with the name Sebastian, in honor of Saint Sebastian the Martyr (commemorated December 18 / 31).

In 1917, Father Stefan was tonsured into the mantia with the name Sebastian, in honor of Saint Sebastian the Martyr (commemorated December 18 / 31).

The Revolution thundered. The centuries-old structure of the Russian state collapsed, and the time of persecution of Christ’s Church began. By a decree of the Soviet of People’s Commissars on January 10 / 23, 1918, Optina Monastery was officially closed, though it continued to exist outwardly as an agricultural commune. On the monastery grounds, a museum called “Optina Pustyn” was organized. The Skete had already ceased to exist, but Elder Nektary continued to live with his attendants in a small hut, weakened under the weight of many sorrows, yet still receiving the faithful.

In 1923, at the end of the fifth week of Great Lent, a liquidation commission began work in the monastery. The divine services were discontinued, and the monks were gradually evicted. Around this time, Father Sebastian was ordained to the rank of hierodeacon.

In March 1923, Elder Nektary was arrested and exiled from the province. At first, he lived in the village of Plokhino (45 versts from Kozelsk), then moved to the village of Kholmishchi in Bryansk Province (about 50 versts from Kozelsk). After the elder’s arrest, Father Sebastian lived in Kozelsk with other brethren of Optina and often visited the elder in exile.

In 1927, Father Sebastian was ordained a hieromonk by the bishop of Kaluga.

On April 29, 1928, Elder Nektary reposed. Following the elder’s blessing, given before his death—that after his repose he should go to serve in a parish—Father Sebastian departed first to Kozelsk, then to Kaluga, and later, at the invitation of the rector of the Church of Saint Elias in Kozlov and the dean Archpriest Vladimir Andreevich Nechaev, he went to Kozlov. There, by appointment of Archbishop Vassian (Pyatnitsky) of Tambov and Kozlov, Father Sebastian was assigned to the Church of Saint Elias.

He served there from 1928 to 1933, until his arrest. In Kozlov, he actively fought against the Renovationist movement, maintained contact with the dispersed brethren of Optina Monastery, and spiritual sisters began to gather around him.

The first to come were the nuns Agrippina, Fevronia, and Barbara, formerly of the destroyed Shamordino Convent, who remained with him for life—they were beside him during his years of imprisonment in the Karlag labor camp and lived with him in Karaganda until his repose.

At that time, other monks and nuns from destroyed monasteries also lived in Kozlov, as well as laypeople who had once visited Optina Monastery. The hearts of those sincerely seeking salvation were drawn by an unseen power toward Father Sebastian—and this, of course, did not escape the notice of the local authorities.

On February 25, 1933, Father Sebastian was arrested together with the nuns Barbara, Agrippina, and Fevronia, and sent to the Tambov OGPU (secret police) for interrogation. During questioning, investigators examined him for contacts with like-minded believers and his attitude toward Soviet power.

To this, Father Sebastian gave a direct answer:

“I view all the actions of the Soviet government as the wrath of God; this power is a punishment for the people. I have expressed such views among those close to me and also among other citizens when we spoke on this subject. I said that we must pray to God and live in love—only then will we be delivered from it. I was displeased with the Soviet authorities for closing churches and monasteries, for by this the Orthodox Faith is being destroyed.”

On June 2, 1933, a session of the Tambov Regional OGPU Troika, after extrajudicial review, decreed:

“Stepan Vasilyevich Fomin, accused under Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code, is to be confined in a corrective labor camp for a term of seven years, the term to be counted from February 25, 1933.”2

Much later, Father Sebastian said of his time in the Tambov OGPU:

“I underwent such a trial: When they forced me to renounce the Orthodox Faith, they made me stand all night in the cold wearing only my cassock, with a guard set over me. The guards were changed every two hours, but I stood motionless in one place. Then the Mother of God spread over me a sort of ‘little shelter,’ and within it I was warm. In the morning they led me to interrogation and said, ‘Since you did not renounce Christ, go to prison,’ and they sentenced me to seven years.”

Father Sebastian was sent to the Tambov Region to work in a logging camp. His spiritual children learned where he had been sent, and despite the great distance, found ways to bring him food and clothing, to comfort and support him as best they could. A year later, Father Sebastian was transferred to the Karaganda labor camp, to the settlement of Dolinka, where he arrived on May 26, 1934.

At that time, Karaganda was a scattered network of small settlements founded in the early twentieth century by migrants from Russia. All around stretched the endless steppe—burned by the scorching sun in summer, and in winter swept by furious blizzards, whose piercing, icy winds cut through every living thing and buried the low adobe houses beneath snow up to their roofs.

In the early 1930s, as part of the effort to develop the virgin lands of central Kazakhstan and to mine the Karaganda coal basin, “dekulakized” (disenfranchised) peasant families, called special settlers, were brought into the area. Their dwellings were mere pits dug in the steppe, covered with anything they could find, just to have some shelter from the wind, rain, and snow. The settlers dug these dugouts themselves. Gradually, they began to build adobe barracks, which were damp and unheated. Unsanitary conditions, lack of bread and water, cold, scurvy, and rampant typhus during the years 1931–1933 led to the mass death of people.

Besides these settlements of special settlers, the Kazakh steppe was soon covered with a network of divisions of the Karlag—a branch of the Gulag, established in 1931. Alongside criminals, victims of political repression were sent there in large numbers. The capital of Karlag was the settlement of Dolinka (33 km from Karaganda); the station of Karabas served as its gateway for arriving prisoners; and the entire boundless steppe of central Kazakhstan became a mass grave for thousands upon thousands of its inmates.

Father Sebastian later recalled his time in the camp:

“They beat and tortured us, demanding only one thing—that we renounce God. I said, ‘Never.’ Then they sent me to a barrack full of criminals. ‘There,’ they said, ‘you’ll be re-educated quickly.’”

One can imagine what the criminals did to the frail, elderly priest.

Because of his poor health, Father Sebastian was assigned to work as a bread-cutter, then as a warehouse guard within the camp zone. In the final years of his imprisonment, he was released from guard supervision and lived in a small supply hut in the third division of the camp, near Dolinka.

He hauled water on ox carts for the inhabitants of the Central Production Department (TsPO). In winter, after bringing the water, he would go up to the oxen and warm his frozen hands on their sides. People would bring him mittens as gifts. The next day, however, he would come again without them—either he had given them away, or they had been taken from him—and once more he would warm his hands against the animal. His clothes were old and threadbare. At night, when he froze, he would climb into the manger among the cattle and warm himself by their body heat. The local residents gave him food—pies, lard. What he could, he ate; the rest he brought to the prisoners in the camp division.

“I was in prison,” he later recalled, “but I never broke the fasts. If they gave me some thin gruel with a bit of meat, I didn’t eat it—I exchanged it for an extra piece of bread.”

The nuns Barbara and Fevronia, who had been arrested together with him, were released without sentence. Sister Agrippina was sent to the Far East, where she was freed after a year. She wrote to Father Sebastian, telling him of her intention to return home, but he blessed her to come immediately to Karaganda.

In 1936, she arrived, obtained permission to visit him, and he advised her to buy a small house in the Bolshaya Mikhailovka district, closer to Karlag, to settle there, and to come to him each Sunday by passing truck.

Two years later, Sisters Fevronia and Barbara also came to Karaganda and bought a small house on Nizhnaya Street—a little old barn with a sagging ceiling. The sisters made acquaintance with local believers, and soon quiet gatherings for common prayer began in their home. When the faithful learned that Father Sebastian was in Dolinka, they began to help him.

On Sundays, the sisters went to visit him in the camp division. Along with food and clean linen, they brought the Holy Gifts, cuffs, and epitrachelion. Together they went into the nearby woods, where Father Sebastian would first partake of Communion himself, then hear their confessions and communicate them.

Both the prisoners and the camp guards grew to love the elder. Love and faith, which filled his heart, overcame hatred and hostility. Many in the camp came to believe in God through him—and not merely to believe, but to have a living, true faith. When Father Sebastian was released, he left behind spiritual children among the prisoners, who later, after serving their own terms, would come to visit him in Mikhailovka. Many years later, when a church was opened in Mikhailovka, the residents of the Dolinka camp division came there and recognized in the venerable old priest their former water-carrier.

As his prison term came to an end, Father Sebastian was released on April 29, 1939, on the eve of the Feast of the Ascension of the Lord. He went to his spiritual daughters’ tiny house in Bolshaya Mikhailovka. The sisters worked to earn their living, while Father Sebastian took care of the household. Together they prayed; he secretly celebrated the Divine Liturgy and daily read the full cycle of the Church services.

Before the war, he traveled to the Tambov Region. His spiritual children, who had long awaited his release, hoped he would remain with them in Russia. But the elder, who sought not his own will but surrendered himself to the will of God, stayed only a week in the village of Sukhotinka, then returned once again to Karaganda—to the lot appointed for him by Divine Providence.

Venerable Confessor Sebastian of Karaganda At that time, the population of Karaganda consisted largely of those bound “permanently” to the coal mines—the same special settlers who had once been exiled there—and of former prisoners of Karlag, released with a document bearing the mark, “permanent exile in Karaganda.” More than two-thirds of the city’s inhabitants had no passports. They lived in dark storerooms, earthen dugouts, or shacks, and every ten days were required to report to the local commandant’s office.

Venerable Confessor Sebastian of Karaganda At that time, the population of Karaganda consisted largely of those bound “permanently” to the coal mines—the same special settlers who had once been exiled there—and of former prisoners of Karlag, released with a document bearing the mark, “permanent exile in Karaganda.” More than two-thirds of the city’s inhabitants had no passports. They lived in dark storerooms, earthen dugouts, or shacks, and every ten days were required to report to the local commandant’s office.

Karaganda was a hungry city, especially during and immediately after the war, when bread was scarce. Father Sebastian himself would go to the store to collect bread rations with his card. He dressed like a simple old man, in a very modest, gray, worn suit. He would take his place in line, and when his turn came, people would push him aside. He would quietly go to the end of the line again—and again, and again. Eventually, people began to notice his meekness and gentleness, and soon they started letting him go first and giving him bread without question.

In 1944, a larger house was purchased on Zapadnaya Street. Father Sebastian went through the house, looking everything over with a practical eye, suggesting what should be repaired or rearranged.

“But, Father,” the sisters objected, “we won’t be staying in Kazakhstan forever! When the war ends, we’ll go home with you.” “No, my dear sisters,” said Father Sebastian, “we will live here. Life here is different, and the people are different—kind-hearted and conscious, having suffered much. So, my dear ones, we will live here. We will do more good here. This is our second homeland—after ten years, we’ve already become accustomed to it.”

In the new house on Zapadnaya Street, a small house church was arranged, where Father Sebastian secretly celebrated the Divine Liturgy.

Once, when Father Sebastian went with the nuns to the cemetery beyond the village of Tikhonovka, they passed by the mass graves in the middle of the burial ground, where two hundred special settlers—who had died each day from hunger and disease—were laid without coffins, without mounds, without crosses. Having seen this and listened to what the people said, the elder remarked:

“Here, day and night, above these common graves of the martyrs, candles burn—from earth to heaven.” And indeed, the elder became a ceaseless intercessor for all those who had perished there.

Time passed. The people of Mikhailovka, having heard of the elder, began inviting him into their homes. He had no official permission to perform the services, yet he never refused anyone. The people of Karaganda were faithful—they would not betray him.

Venerable Confessor Sebastian of Karaganda Not only in Mikhailovka but throughout the surrounding districts, the elder’s reputation spread; people believed in the power of his prayer. Spiritual children of the elder—monastics and laity alike—began to arrive in Karaganda from all over: European Russia, Ukraine, Siberia, the far North, and Central Asia. All came seeking spiritual guidance. Father Sebastian received everyone with love and helped them settle in this new land.

Venerable Confessor Sebastian of Karaganda Not only in Mikhailovka but throughout the surrounding districts, the elder’s reputation spread; people believed in the power of his prayer. Spiritual children of the elder—monastics and laity alike—began to arrive in Karaganda from all over: European Russia, Ukraine, Siberia, the far North, and Central Asia. All came seeking spiritual guidance. Father Sebastian received everyone with love and helped them settle in this new land.

Meanwhile, Karaganda itself grew and developed. It absorbed the once-separated steppe plots, mines, and old settlements of special settlers and German colonists exiled there from the Volga region during the war. The first area built up was Kopai Town, then the 1st and 2nd Mine settlements, followed by Old Town near the major mines. After the war, construction began on the New Town, which expanded rapidly as the new regional center. The district of Mikhailovka lay closest, adjoining New Town directly. Yet there was only one functioning church in all of Karaganda—at the 2nd mine.

In November 1946, with the elder’s blessing, the Orthodox residents of Bolshaya Mikhailovka submitted a petition to the local authorities requesting registration of a religious community. When this request was denied, the faithful repeatedly appealed to Alma-Ata and even traveled to Moscow to seek permission.

For a time, services continued quietly in the Mikhailovka prayer house, but in 1951 it was finally closed. Only in 1953 did the believers succeed in obtaining official permission to perform church sacraments and rites—baptisms, funerals, weddings, and confessions—in the Bolshaya Mikhailovka prayer house. After that, many more people could turn to Father Sebastian for spiritual help.

The Bolshaya Mikhailovka parish served not only the New Town but also the districts of Melkombinat, Fedorovsky Mine, Mikhailovka Station, Sarany, Dubovka, Ten Kirzavod factories, Novostroika, the five Karaganda open-pit coal mines, and several other localities—altogether about twenty settlements.

Father Sebastian was alone, assisted only by the nuns. His chief difficulty was that he could celebrate the Divine Liturgy only in secret, in private homes of believers. After a long day of work and his own evening prayers, the elder would set out at three in the morning through the dark streets of Karaganda to a designated house, where small groups of faithful would gather quietly, two or three at a time.

On the great feasts, Vigil would begin at one in the morning, and after a short rest, the Divine Liturgy followed. The service would be completed before dawn, and the faithful would leave discreetly, one by one, to their homes.

The efforts to open the church continued. Again and again, Alexander Pavlovich Krivonosov, a man deeply devoted to Father Sebastian, traveled to Moscow to petition for the necessary authorization. At last, in 1955, he returned with the long-awaited official document registering the Orthodox community in Bolshaya Mikhaylovka.

Reconstruction began immediately to convert an ordinary residential house into a proper church building, with Father Sebastian personally supervising every stage. The inner walls were removed, the floor was deepened, and a small sky-blue onion dome was built upon the roof. In 1955, on the Feast of the Ascension of the Lord, the new church was solemnly consecrated in honor of the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos. Father Sebastian served as its rector for eleven years, from 1955 to 1966, until the day of his repose.

On December 22, 1957, the Feast of the Icon of the Mother of God “Unexpected Joy,” Father Sebastian was elevated to the rank of archimandrite by Archbishop Joseph (Chernov) of Petropavlovsk and Kustanai and was awarded a Patriarchal Gramota “for zealous service to the Holy Church.”

In 1964, on his name day, he received a most exceptional honor—a bishop’s staff—a distinction virtually without precedent for a simple parish priest.

Shortly before his blessed repose, Father Sebastian was tonsured into the Great Schema.