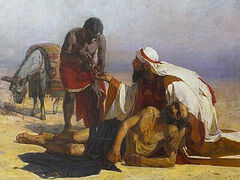

The first panel from the polyptych, The Seven Works of Mercy. Artist: Master of Alkmaar Christian life is difficult. Indeed, in essence, it is a narrow, straight and thorny path of spiritual ascent along the steps of the Gospel commandments. Ascending is always difficult. It’s easiest to stand still or go down. The higher the peak, the harder it is to go up.

The first panel from the polyptych, The Seven Works of Mercy. Artist: Master of Alkmaar Christian life is difficult. Indeed, in essence, it is a narrow, straight and thorny path of spiritual ascent along the steps of the Gospel commandments. Ascending is always difficult. It’s easiest to stand still or go down. The higher the peak, the harder it is to go up.

The Lord calls on us to reach the peak, the highest of all possible peaks, and wants us to take up our cross and follow Him to the mountain of Gospel holiness. There is a path leading there, consisting of nine main steps—the Gospel Beatitudes.

The Beatitudes are not just a moral code, a set of moral norms, but a mysterious picture of the image of the New Man who is born and develops in us as we follow Christ (cf. Col. 3:8–10; Eph. 4:22–24).

It is written on the fifth step of the ladder leading us to the Heavenly Kingdom promised by Christ:

Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy (Mt. 5:7).

At first glance, this Beatitude seems so simple and clear. Who doesn’t know that mercy is a virtue? Who wouldn’t agree that helping others is good and right? But is this Gospel word really that simple? Let’s look at it more closely to see at least a part of the ocean of spiritual meaning that it contains.

What Is True Mercy?

In the everyday sense, mercy is giving alms to a beggar, donating to church, or helping an old woman who can’t cross the street on her own. Undoubtedly, these are good works. But Christ spoke about something greater. The Greek word “ἐλεήμων”, translated as “merciful”, has the root “ἕλεος”—”mercy”, “pity”, “compassionate love”. This is not just a single act, but a state of the heart, a property of the soul that becomes natural to you.

St. John Chrysostom explains that a merciful person is someone who “has a heart capable of taking pity on all who suffer.” It is not only and not so much about financial help, but about deep, heartfelt concern, about the ability to put yourself in another person’s place, to feel his pain as your own. It is a gift of empathy, compassion and humaneness. An unmerciful person is cruel and inhumane, and therefore godless.

“To be merciful means to be human; for to show mercy means to be God,” St. John emphasizes.1

Mercy is manifested in many different forms. This is, of course, external, physical mercy:

-

To feed a hungry person,

-

To quench somebody’s thirst,

-

To clothe somebody who is naked,

-

To visit a sick person or a prisoner.

As Christ tells us in the Parable of the Last Judgment:

Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these My brethren, ye have done it unto Me (Mt. 25:40).

Every act of mercy that we do for our neighbor we do for Christ personally.

But there is another, no less, and perhaps even more important mercy—inner, spiritual mercy. St. Isaac the Syrian called it a “merciful heart” that “cannot bear to see or hear any harm or sorrow endured by a living creature”, and therefore prays even for enemies and for demons.2 Spiritual mercy means:

-

To forgive an insult, even the most bitter one, remembering the words of Christ: Forgive, and ye shall be forgiven (Lk. 6:37).

-

To be able to make concessions, sacrificing your self-love and personal truth for the sake of peace and love for another.

-

Not to judge the sinner, but to pray for his reform, seeing in him the image of God, marred by sin.

-

To comfort a grieving person with a word of hope, to cheer up somebody who is discouraged.

-

To suffer the infirmities of your brother—that is, to respond to his weaknesses and shortcomings with patience and love.

-

To teach somebody who has gone astray the path of truth—not with the arrogance of a Pharisee, but with meekness and love.

This spiritual mercy is the criterion of our genuine love for our neighbor. It’s easy to throw a coin to a beggar, but it’s much harder to forgive someone who has wronged you. It’s easy to donate to charity, but it’s much harder to spend your time listening to a lonely person and sharing in his sorrow.

A truly merciful person does not show mercy for his own advantage, or for appearances’ sake, or to be praised, but because he cannot do otherwise. His heart becomes like the heart of Christ, and He pours out love and compassion on everyone around.

For They Shall Obtain Mercy

And now let’s turn to the second, wonderful part of this Beatitude. Here the Lord reveals to us a spiritual law, inviolable and universal: the measure of our mercy to our neighbors determines the measure of God’s mercy to us.

This is not a “deal” with God or a mechanical exchange: “I give you a dollar, and You, Lord, forgive my sin.” No. This is an ontological, essential law of spiritual life. The mercy that you show to others is evidence that your heart has become merciful—that is, it has become like God’s heart. And what kind of heart can accept God’s mercy? Only a heart that can contain it—that is, a merciful one.

Let’s recall the terrible Parable of the Unforgiving Debtor (cf. Mt. 18:23-35). The king forgave his servant a tremendous debt—an image of our sins before God. But the latter left the king, seized his fellow servant, who owed him a very small amount, and, not listening to his pleas for mercy, threw him into prison. Having learned of this, the king got angry and handed the servant over to the tormentors in jail until he paid off all the debt. And Christ concludes:

So likewise shall My Heavenly Father do also unto you, if ye from your hearts forgive not every one his brother their trespasses (Mt. 18:35).

Here is the key! From your hearts. God does not require formal, external forgiveness from us. He waits for our hearts to change and become like His—forgiving and merciful. When we deny mercy to our neighbor, it is as if we were saying to God through our actions, which are louder and more eloquent than any words: “I don’t accept Thy law of love—instead I want to live by my own law of judgment and revenge.” And then we cut ourselves off from the flow of the mercy of God. We close the doors of our hearts to forgiveness.

The Holy Fathers teach that at the Last Judgment we will be judged not so much by the list of sins and good works we have, but by what we have become in our hearts. What is the state of our souls? Do we have merciful hearts? If so, they will be recognized by God as His kind. But if our hearts are hardened, filled with condemnation, rancor and hatred, how can we enter the Kingdom of Love, even if formally we “did nothing wrong”?

Acquiring Mercy

How can we, weak beings, full of self-love and resentment, become merciful? This gift is not acquired overnight. It’s a lifetime’s work.

Firstly, to start with awareness. Look honestly into your hearts and see where you are unmerciful. Whom do you judge? Whom do you envy? Against whom do you harbor a grudge? Whom do you refuse to help, considering him “unworthy”? Admitting your callous-heartedness is the first step.

Secondly, to remember God’s mercy to you. Every day, every hour and every moment you should keep in mind how much the Lord forgives you. Each of your sins is an endless debt to the Loving Father (cf. Mt. 6:12). And He forgives us again and again, if only we would repent. Boundless and infinite is God’s mercy to the repentant sinner! Once we truly realize this, resentment against our neighbor for any wrongdoing will become so insignificant and foolish in our eyes.

Thirdly, to force yourself to show mercy. Since our fallen selves resist, we must force ourselves to perform acts of mercy, even if we don’t want to. The Holy Fathers call this “forcing yourself”. To smile at someone whom we find disagreeable. To refrain from a biting retort. To give alms, even if it seems that the suppliant does not deserve it. To overcome ourselves and apologize first after an argument. Let it at first be difficult, not very sincere, and “mechanical”. But just as physical exercises gradually make the body stronger, so exercises in mercy gradually soften and heal the heart.

Fourthly, to pray for the gift of a merciful heart. We can do nothing without God’s help. Therefore, we must pray fervently with the words of the Gospel publican: God, be merciful to me, a sinner (Lk. 18:13). We can also do it in our own words, as long as our prayer is heartfelt and sincere: “Lord, grant me a merciful heart, grant me to see Thy image in my neighbor, help me forgive, just as Thou forgivest me.” It is especially important to pray for those whom we cannot forgive. Prayer for your offender is a powerful tool for healing the heart and a direct command of the Lord:

But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you (Mt. 5:44).

Fifthly, to participate in the sacraments of the Church. In the sacrament of confession we obtain forgiveness from God and the grace to forgive others. In the sacrament of the Eucharist we partake of the Source of all mercy—the Body and Blood of Christ. This mysterious union with Christ can transform our souls and make our hearts capable of true, sacrificial love.

The Bliss of the Merciful

Blessed are the merciful is not just a beautiful phrase. This is the promise of the highest happiness—the happiness of becoming like God and of union with Him. God is Love (1 Jn. 4:8), and to be merciful is to be a partaker of this Divine Love.

To be merciful means to love genuinely, the way God loves:

Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; Rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; Beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. Charity never faileth… (1 Cor. 13:4–8).

A merciful person already enjoys bliss here on earth. A merciful heart does not contract in spasms of anger and resentment, nor is it torn by envy and hatred. It is free and completely open to God and other people. A merciful person does not waste his strength, does not waste himself on judging and hatred. All his desires and talents are directed at service and constructive endeavors in love. Therefore, a merciful person is spiritually healthy and strong. He does not see an enemy or a rival in everyone, but a brother, albeit a lost one, for whom Christ shed His redemptive Blood. And most importantly, he can boldly hope for God’s mercy on the Day of the Last Judgment.

For they shall obtain mercy. There is great consolation in these words. This means that the fate of our souls is in our hands. Or rather, in our hearts. We ourselves determine which way we will be measured and judged: cruelly and unmercifully or mercifully and forgivingly (cf. Mk. 4:24).

Let us ask the Lord for this great gift of a merciful heart. Let us learn from Him, Who is meek and lowly in heart (cf. Mt. 11:29), show mercy and forgive. Let us perform works of mercy, both physical and spiritual, remembering that everything we do for the least of the people, we do for Christ Himself.

And then we will be heard, because already here on earth we have striven to become instruments of His mercy for the world. And the promised bliss will be poured out abundantly onto our souls.