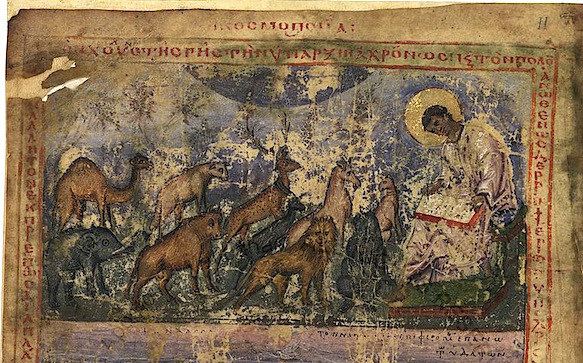

The Prophet Moses receiving from the Lord the tablets of the Law

The Prophet Moses receiving from the Lord the tablets of the Law In the Nicene Creed, our Symbol of Faith, we confess that the Holy Spirit “spake by the prophets.” Usually the idea of a “prophet” is associated with foretelling the future—it is for prophets to speak of coming times, and especially the eschaton, or to proclaim the coming wrath of the Lord should the people not repent. The prophet Daniel and St. John the Theologian were granted visions of the end of days, and prophets such as Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Jonah came with the voice of the Spirit preaching repentance.

However, in a broader sense, a prophet is anyone who speaks for God—he need not necessarily speak of the future. When an elder gives a saving word to his disciple he is, in fact, carrying on the prophetic ministry in the Church. And the Scriptural witness shows us that a prophet is not simply a messenger or middleman between God and His creation, but moreover a prophet is a visionary—that is, he sees and experiences what he proclaims. In the first chapter of his Revelation St. John tells us that he writes that which he saw. St. Justin Martyr proclaims:

They are called prophets. These alone both saw and announced the truth to men, neither reverencing nor fearing any man, not influenced by a desire for glory, but speaking those things alone which they saw and which they heard, being filled with the Holy Spirit.[1]

In this broader context we can speak of the holy prophet Moses as a prophet of the past. Despite lingering theories of the Pentateuch as a compilation of sources by some later redactor, Church Tradition, first and foremost the words of Christ Himself (for example, John 5:46), confirm for us its Mosaic authorship. Moses is no mere historian, but, in fact, atop Mt. Sinai he spoke with God face to face, as one speaks to a friend (Exodus 33:11). Such communication with God is to experience the glory of God, it is to see in the Spirit, and the Patristic Tradition confirms that when Moses writes of the creation of the world he is writing, as did St. John, that which he saw. St. Ambrose writes, “Plainly and clearly, not by figures or riddles, there was bestowed on [Moses] the gift of the divine presence.”[2] St. Justin further reveals the full scope of these prophetic visions: “[The prophets’] writings are still extant, and he who has read them is very much helped in his knowledge of the beginning and end of things”[3] (emphasis added).

Moreover, Moses bears a unique role in the Biblical canon as St. John Chrysostom proclaims to us:

All the other prophets spoke either of what was to occur after a long time or of what was about to happen then; but he, the blessed (Moses), who lived many generations after (the creation of the world), was vouchsafed by the guidance of the right hand of the Most High to utter what had been done by the Lord before his own birth.

And therefore, St. John exhorts us to humility: “Let us pay heed to these words as if we heard not Moses but the very Lord of the universe Who speaks through the tongue of Moses, and let us take leave for good of our own opinions.”[4]

Of course the Church does not discount the value of human contribution and historical research. Christ wrought our salvation in His two natures and so it is by our synergy that we are saved. We are called to “crucify” our minds before the wisdom of the Church, but not to obliterate our minds. Here Fr. Seraphim Rose has an important word on synergy: “One can believe that Moses and later chroniclers made use of written records and oral tradition when it came to recording the acts and chronology of historical Patriarchs and kings,” but he continues with a crucial distinction: “but an account of the beginning of the world’s existence, when there were no witnesses to God’s mighty acts, can come only from God’s revelation; it is a supranatural knowledge revealed in direct contact with God.”[5]

Fr. John Romanides offers a helpful note on the limit of academic scientific and philosophical pursuits:

If we begin with philosophical and scientific observations of the material world, it is logically impossible to arrive at a distinction between the creation of the world and its fall. Quite simply, this is because the reality before our eyes presents nature as it is now, after the fall … Philosophy is unable to bridge [its] dualism between matter and reality because it is impossible for natural man to distinguish between the wholly positive creation of the world and the fall of the world.

But there is a means by which the veil is lifted from the creative acts of God: “Man cannot know this division except by revelation,” by which “the Prophets, the special people of God learned to distinguish clearly between the world’s creation and the world’s fall.”[6] Thus it is to Moses as a prophet of the past that we turn.

That the prophets, and here particularly Moses, beheld the word and will of God in vision is a consistent teaching of the unbroken Orthodox Tradition, which, as we have seen, began with Scripture and the earliest of fathers such as St. Justin Martyr in the second century. Writing in the second-third centuries, Clement of Alexandria tells us that knowledge,

When perfected in the mystic habit, it abides, being infallible through love. For not only has he apprehended the first Cause, and the Cause produced by it, and is sure about them … respecting all about Which the Lord has spoken, he has learned, from the truth itself, the most exact truth from the foundation of the world to the end.[7]

In his Hexaemeron St. Anastasius of Sinai writes in the seventh century: “And accordingly the Church also learns that the divine prophet Moses not only saw the making of creation, but also foresaw it being led into the good existence.”[8] In the fourteenth century the great hesychastic father among the fathers St. Gregory Palamas wrote of Moses’ prophetic vision: “Then on the seventh day God rested from all His works, as we are taught by Moses (Gen. 2:2), who was born later, but beheld the foundation of the world long before his time”[9] (emphasis added). Nearer to our own times the great wonderworker St. John of Kronstadt chastises those who seek to discern the mind of God concerning the creation of the world from any source other than “the Divinely-inspired words of the great prophet Moses, who saw God[10] (emphasis added). Nearer still, St. Nicholai Velimirovich preached: “For human understanding and human logic, however great they may be, are too puny to reach to the world’s beginning and its end. Understanding is useless where vision is needed,”[11] and indeed, we know of the creation of the world from the divine vision granted unto the prophet Moses.

But why do the saints of the Church consistently maintain that Moses not only heard of the creation of the world, but actually beheld it as a witness? How can they be sure if Moses himself did not state as such directly? The answer can be found in another teaching of the fathers, which we find laid out plainly in the writings of St. Isaac the Syrian. Describing the highest stages of the spiritual life in which man joyously contemplates the future life of incorruption, he writes:

And from this one is already exalted in his mind to that which preceded the (making) of the world, where there was no creature, no heaven, no earth, no angels, nothing of that which was brought into being, and to how God, solely by His good will, suddenly brought everything from non-being into being, and everything stood before Him in perfection.[12]

Thus we see that in the age of the Church, following the Lord’s Incarnation, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension, and the giving of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost, the saints, like Moses, are also granted vision of the creation of the world. They recognize in the words of Moses their own experience and thereby confirm for us the words of Moses written from the face to face vision of God. The testimony of St. Isaac is confirmed by St. Anastasius of Sinai who wrote that while God does not give to know His essence, “Yet he makes other things visible to others—to those that have been empowered with spiritual vision. They see such things as angels, heaven, and all of creation (I mean how and from where it came into being).”[13] In our own times, the great Athonite luminary and disciple of St. Isaac the Syrian, St. Paisios, while one day conversing with a monk who referred to the Psalm I went down into the depths of the waters (Ps. 68:2), said to him:

The prophet David, our saints, Basil the Great, who wrote about creation, all of them, with the grace of God knew everything about the creation by God. The Holy Spirit took them to the depths of the waters, He showed them and they saw the earth revolving around the sun, and many other things.[14]

Confirming the Athonite’s words, his contemporary and fellow Athonite, the former abbot of Vatopedi monastery, Elder Joseph who reposed in 2009, a spiritual child of the inestimable Elder Joseph the Hesychast, is said to have beheld a vision of the creation of the world, in which he saw precisely that which is written by Moses.[15]

Of course we believe in a good God Who does all that He does for a purpose—in order to bring man and all of creation to Himself, and the Scriptures are the foremost manual or guidepost on our path to salvation. Thus we need not wonder why God should make known His creation of the world to Moses in vision plainly, face to face and “without riddles,” in the words of St. Basil the Great,[16] and why He should grant it to be included in Holy Writ. As we know in part the character and will of God, we know that the knowledge of the creation of the world is for the good of our salvation. On this St. John Chrysostom states,

The blessed Moses, instructed by the Spirit of God, teaches us with such detail ... so that we might clearly know both the order and the way of the creation of each thing. If God had not been concerned for our salvation and had not guided the tongue of the Prophet, it would have been sufficient to say that God created the heaven, and the earth, and the sea, and living creatures, without indicating either the order of the days or what was created earlier and what later.... But he distinguishes so clearly both the order of creation and the number of days, and instructs us about everything with great condescension, in order that we, coming to know the whole truth, would no longer heed the false teachings of those who speak of everything according to their own reasonings, but might comprehend the unutterable power of our Creator.[17]

As we know that God revealed His creative acts to Moses for our salvation, we know also that He continues to grant that same vision to fathers and saints of every generation, inspiring them to spill ink over thousands of pages on the theme. To understand creation is sanctifying, and thus our Lord graciously preserves such knowledge inviolate in His holy Church.

The prophet Moses occupies a unique position in the Scriptural Tradition of prophecy, having been granted not only to see the future and call the people to a greater faith in God, but alone was given to see the awesome creation of the world—that which God alone witnessed, and God alone can reveal. Moses, alone in the Scriptural canon can be called a prophet of the past, and his experience is confirmed for us in the experience of the saints in every age of the Church. He responded to the call of God and ascended the mountain to speak with Him, experiencing divine vision in His presence, and in turn offering to us the life-giving knowledge of the creation of the world, and there arose no greater prophet in Israel like unto Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face (Deut. 34:10).

Let Moses, the first among the prophets, be praised, for he was the first to converse openly with God, face to face, not in indistinct images, but beholding Him as in the guise of the flesh.[18]