The term “ecumenism” has become charged with such emotions both negative and positive, depending on which side of the ecumenist dialogue you stand. The connotations range from politically correct to heresy. Author Julija Vidovic investigates ecumenism from the point of view of two great theological luminaries of the Orthodox Church in recent times, St. Nikolai Velimirovic and St. Jutin Popovic.

St. Nikolai Velimirovic and St Justin Popovic share the position of the entire Orthodox Church on ecumenism. Our dialogue with non-Orthodox is the evangelical responsibility that is specific to the very nature, to the very essence of the Orthodox Church, which is the same Church that the Lord founded on Himself as eternal stone (1 Corinthians 3:11). It is our duty to bear witness to the Risen Lord to the end of the world. This mission was entrusted to the Apostles, and the Orthodox Christians do not have the right today, after two thousand years, to withdraw from it.

However, a profound interest and involvement in the ecumenical movement implies questioning and criticism of it? We should not stand silently by without pointing out the problems that arise within the ecumenical movement when, represented by certain organizations, it begins to meddle in political and national issues while the essential question—the unity of the Christian world—remains in the shadows. How can the Orthodox Church (and indeed other churches) participate in a movement which could ultimately destroy the very foundations of the Christian faith and morals?

As we have concluded that on the one hand, we do not have the right to withdraw from efforts toward ecumenical dialogue, and that on the other, we have ever rising discontent with the development of the broader ecumenical movement, the question is whether it is time to design a new model, a new formula of ecumenism which would allow us to interact with each other and collaborate in a more positive way? This does not mean that we need to, or should, abandon and forget all the important work that has already been done: convergence, better knowledge and understanding of each other impregnated with love, but having in mind and heart to make a step forward. For this new model of dialogue and collaboration we have an inexhaustible source in the works of Nikolai Velimirovic and Justin Popovic, and especially by using their severe criticism of the consideration of ecumenism as an ideology.

Both Bishop Nikolai and Fr. Justin represent what Bishop Athanasius (Yevtic) calls “the Orthodox ecumenism”.1 This means that the whole truth of our Christian faith is the revelation of the Holy Trinity in Christ, in His Incarnation. The body of this truth, as Fathers of the Church often stated, is the Church as the Body of Christ. Therefore, for us Orthodox, the Ecclesiology so actual in our times is derived from, based on and inseparable from Christology. “The union of God and man in Christ, our own union with God, with His creation (= the whole world) and other people, is in the cosmic and, in the same time, in the concrete historical, ecclesiastical body of the Church of Christ. For this reason bridging of all chasm, abyss, and 'dualism'—that cannot exist alongside the Person of Jesus Christ, God-man—is an essential feature of the Orthodox vision of the world and of man, and therefore of the Orthodox ‘ecumenism’.”2

From this movement, which is certainly not a new one, all “Orthodox ecumenists” proceed, i.e. ecumenical people, people not of exclusiveness, but of inclusiveness, comprehensiveness, as the young Nikolai Velimirovic used to say, or people of unity, conciliarity, according to Fr. Justin Popovic.3

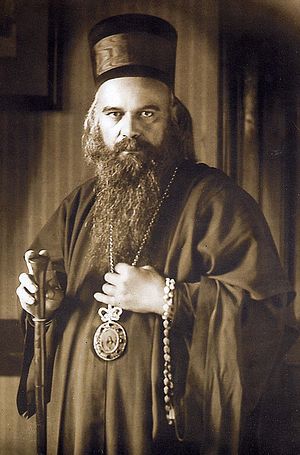

Saint Nikolai Velimirovic (1880-1956) was bishop of Ohrid and of Zhicha in the Serbian Orthodox Church. As an influential theological writer and a highly gifted orator, he became known as ‘the New Chrysostom.’4 Bishop Nikolai strongly supported the unity of all Orthodox Churches and established particularly good relationships with the Anglican, the Old Catholic and the American Episcopalian Church. His presence in England during the years of the Great War did much to strengthen the friendship between the Church of England and the Eastern Orthodox Churches in general, and the Serbian Church in particular. His original Christian eloquence made a deep impression and his warm personality won him many friends. As the Bishop of London wrote at the time: “Father Nikolai Velimirovic by his simplicity of character and devotion has won all our hearts”.5 In his lifetime, Bishop Nikolai visited the United States of America several times, and perhaps of all Eastern Orthodox churchmen was the best known to America. After his speech at the Institute of Politics in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1927, a reporter covering the event wrote:

“His black monk's robe, his long black beard, and his dark, living eyes, set in an oval Slavic face, gave him an appearance which contrasted as strongly with that of conventionally dressed professors and diplomats as did his views of the common problems of world peace contrast with theirs. His charm and urbanity of manner, the completeness of his grasp upon international problems only emphasized the difference in his thought … Bishop Nikolai, speaking from the point of view of a civilization in which men still are more important than institutions, points out that peace or war is a matter of the way men think and feel toward each other, and that all other things are only outgrowths of this. The greatest force for affecting men's attitudes toward each other he believes would be a reunited Christian Church”.6

Nikolai's attitude toward ecumenism is shown by his participation, as an Orthodox bishop and theologian, in the ecumenical meetings and dialogues between the two World Wars, and later he was present, as the accredited visitor, at the meeting of the World Council of Churches in Evanston, Illinois, in 1954.

In his approach to ecumenism we can distinguish two different phases. In his early works, Bishop Nikolai considered the prerequisite for the achievement of union among the Churches to be not so much agreement in doctrine as mutual love. He wrote in The Agony of the Church:

“The Church of England cannot be saved without the Church of the East, nor the Church of Rome without Protestantism; nor can England be saved without Serbia, nor Europe without China, nor America without Africa, nor this generation without the generations past and those to come. We are all one life, one organism. If one part of this organism is sick, all other parts should be suffering. Therefore let the healthy parts of the Church take care of the sick ones. Self-sufficiency means the postponement of the end of the world and the prolongation of human sufferings. It is of no use to change Churches and go from one Church to another seeking salvation: salvation is in every Church as long as a Church thinks and cares in sisterly love for all other Churches, looking upon them as parts of the same body, or there is salvation in no Church so long as a Church thinks and cares only for herself, contemptuously denying the rights, beauty, truth and merits of all other Churches. It is a great thing to love one's Church, as it is a great thing to love one's country, but it is much better to love other Churches and other countries too. Now, in this time, when the whole Christian world is in a convulsive struggle one part against the other, now or never the consciousness of the desire for one Church of Christ on earth should dawn in our souls, and now or never should the appreciation, right understanding and love for each part of this one Church of Christ on earth should dawn in our souls, and now or never should the appreciation, right understanding and love for each part of this one Church begin in our hearts”.7

It seems that at first he emphasizes only love and has little to say regarding the theology of the Orthodox Church. However, as bishop Athanasius pointed out, this does not mean that he denies the authenticity and uniqueness of the Eastern Orthodox Church, nor does he consider her lacking or defective in any way;8 rather, in the context of the wartime drama encompassing his and other European nations, he sincerely wishes for the unification of all European Christian communities for their benefit and for the benefit of other Christians in the world.9 He clearly expresses the Orthodox stance with regard to the ideal of Church unification: “We must return to the only source of Christian strength and majesty—to the spirit of Christ. This rebirth and the revival of Christianity are possible only in a united Church of Christ. This unity is possible only if built on the foundations of the original Church.”10 The above quotation confirms that in the Saint Nikolai’s opinion, there is continuity in two things: 1) only the Orthodox Church has the plenitude of Christ, but this is not her own treasure but the treasure of Christ accessible to everyone; 2) the relationship of the Orthodox Church with other Churches must be a relationship of love, so that they can recognize the treasure that carries the Orthodox Church.

However this explains also his harsh criticism of:

The poverty of European civilization. He observes that the spirit of any civilization is inspired by its religion, and whenever we divide a civilization from her religion, she is condemned to die. He states that “the Christian religion, which inspired the greatest things that Europe ever possessed in every point of human activity, was degraded by means of new watchwords; individualism, liberalism, conservatism, nationalism, imperialism, secularism, which in essence meant nothing but the de- Christianization of European society, or, in other words, emptiness of European civilization.”11 That leads him to conclude that Europe, in abandoning Christ, abandoned all the greatest things she possessed and clung to the lower, and indeed the lowest, ones.

The secularization of the Church. According to Bishop Nikolai, “Liberalism, conservatism, ceremonialism, right, nationalism, imperialism, law, democracy, autocracy, republicanism, socialism, scientific criticism, and similar things have filled Christian theology, Christian service, Christian pulpits as the Christian Gospel. In reality the Christian Gospel is as different from all these worldly ideas and temporal forms as heaven is different from earth. For all these worldly ideas and temporal forms were earthly, bodily—a convulsive attempt to change unhappiness for happiness through the changing of institutions. The Church ought to have been indifferent towards them, pointing always to her principal idea, embodied in Christ. This principal idea never meant a change of external things, of institutions, but rather a change of spirit. All the ideas named above are secular precepts to cure the world's evil, the very poor drugs to heal a sick Europe, outside of the Church and without the Church.”12

He concludes that Church ought to give an example to secular Europe: an example of humility, goodness, sacrifice—saintliness. And he asks: “Which of the Churches ought to give this example for the salvation of Europe and of the world?” and answer, “Whichever undertakes to lead the way will be the most glorious Church. For she will lead the whole Church, and through the Church, Europe, and through Europe, the whole world, to holiness and victory, to God and His Kingdom.”13

As we can see from the passages quoted above, the first period of Nikolai's maturation and thoughtful presentation of his understanding of man, the Church, the world, the global society, and God, is full of quests and questioning, sometimes even rebellion and revolutionary zeal, seeking for something deeper and more holistic. In this period he will write, entirely in the movement of the spirit of his time that “Christianity is not a museum where everything is set from the start, but a workshop in which the roar of labor never stops.”14 All his questing for the grasp of dead ideas and petrified structures of thought and life are in fact the pursuit of and the struggle for a living faith in the living God, the deep inner meaning and structuring of the whole being.

Metropolitan Amphilocus notes: “While being in constant dialogue with Europe and America, in his first period of life, we can say that Bishop Nikolai considered himself, especially toward Europe, as a student.”15 He was tied to the reality of the societal currents and messianic enthusiasms of his time, distinctive to Europe and to European intellectual and ecclesiastical circles in the first half of the twentieth century. But in his mature period, in the wartime and postwar time—sobered by Nazism and Bolshevism, and after experiencing Dachau—he no longer behaved toward Europe as a student but rather as a prophet who, in the spirit of the Old Testament prophets, felt responsible for not only for his people but for all the people of Europe and the world without exception.16

Nikolai begins in his youth with a kind of ecumenical humanistic vision of the Church, but in deepening his experience of the Church (which was the result of his encounter with Orthodox Russia, the Ohrid of SS. Clement and Naum, and the Holy Mountain of St. Sava and other Athonite Fathers), he develops a clear distinction between "heterodox churches" and the Orthodox Church. He goes even further in The Century from Ljubostinja,17 writing that in the Christian world only the Orthodox Church holds the Gospel as the only absolute truth and is not governed in the spirit of this century.”18 In many aspects he came close to the ways of the early Christians, the Apostles and Church Fathers, who introduced theology into everyday life, who not only lived by it but also with it.19 This is the reason why he reproaches most sternly Western Christianity for its easy adaptation to worldly circumstances. Thus the main difference between East and West, according to him, is in "a different understanding of the Gospel of Christ—the West understands it as a theory, one of the theories, and the East as an ascetical struggle (podvig), and practice."20

However, this does not mean that Bishop Nikolai was no longer open to ecumenical dialogue. That would be in complete opposition to his inner being; that of a truly godly man who realized and achieved a balance between the individual and the general, the material and spiritual, God and man, national and pan-human. He was able to succeed in doing this through the mystery of Christ, the Only Lover of man, as he called Him in one of his final works, in the mystery of Christ’s Orthodox Church. Thus we can read in his inspired report from the Second Meeting of the World Council of Churches held in Evanston, Illinois, 15-31 August 1954:

“In Evanston, one name brought all together and closer—Jesus Christ”; he continues: “As mentioned later (in the statement of Florovsky)21 the fact that if each denomination contains only a part of the Christian faith, only the Orthodox Church contains the totality and plenitude of the true faith, ‘which was transmitted to the saints once and for all’ (Jude 3). Hope in Christ [an allusion to the theme of the meeting] is based on the true and whole faith, for it is written: first faith, then hope and then love, otherwise it is a house without foundation. The same applies to eschatology which was contained in that faith from the beginning. Without such faith, it is difficult to approach with truth the Christ who is considered as the complete Hope, as well as the eschatological Christ who is destined to accomplish human history and to be the eternal Judge. The union of all the churches cannot be achieved through mutual concessions but only by adherence by all to the one true faith in its entirety, as it was bequeathed by the Apostles and formulated at the Ecumenical Councils; in other words, by the return of all Christians in the one and indivisible Church to which belonged the ancestors of all Christians in the entire world during the first ten centuries after Christ. It is the Holy Orthodox Church.”22

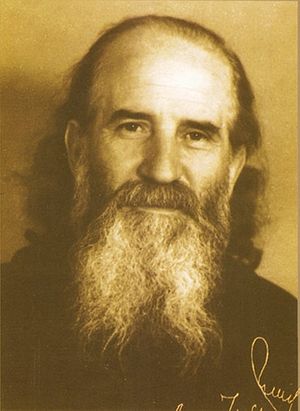

Saint Justin Popovic’s (1894-1979) criticism of ecumenism was deeper and more theologically founded than that of Bishop Nikolai. He, as Bishop Athanasius notes, never actively participated in meetings and ecumenical dialogues. However, during his studies in England (1916-1919) he was inquiring of Bishop Nikolai, who was active, as we have seen.

When addressing his critique of ecumenical dialogue we must bear in mind the historical context. Justin Popovic spoke about it at the time of the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras. The latter made several audacious statements, saying that there were no real obstacles to the establishment of the unity of the Church and that the difficulties came only from theologians and theology. Patriarch Athenagoras made statements full of emotion and daring, and gave the impression that a new category of ecumenists had appeared in the Orthodox world. In a testimony on Saint Justin, Irenaeus (Bulovic), one of his faithful disciples and one of the most active representatives of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the ecumenical dialogue of our times, noted: “I feel that voices like that of Father Justin, often harsh and critical, have ensured that the course of events should not take a different direction. Father Justin, this is how I understand it now, after raising this issue with him often, never criticized the idea of dialogue, witness and love. He was himself an extremely open person. But he criticized the ideology of ecumenism, considered as a variant of the 'new Christianity', as an ecclesiological heresy. He felt it as a dangerous heresy and he even forged a new term, now widely used, that of the ‘pan- heresy’.”23 But unfortunately in our times, men and groups who most often refer to this term are, as to their position, both theological and spiritual, well below of that of Justin Popovic.

Those who hold the position that Justin Popovic was an anti-ecumenists most often refer to his study Orthodox Church and Ecumenism.24 However, as noted by his disciple and collaborator, Bishop Athanasius (Yevtic), who perhaps best understood his thought, “this book was not written specifically on that subject, but quickly redacted from the unfinished manuscript of Father Justin, who was then working on the third and final Book of Dogmatic, which gives a fuller and richer picture of Justin’s ecclesiology”.25 According to Bishop Athanasius, Justin Popovic does not reject the term “ecumenism”, which in his writings is usually identified with the Roman Catholic and Protestant humanistic tendencies toward Christian unity, but following the methodology of the Church Fathers who transformed the terminology of pagan philosophy, he fills this term with a new meaning and content.26 On this specific point Vladimir Cvetkovic notes that: “as he (Fr. Justin) finds the substitute for humanism in the God-humanism, he also replaces the idea of western ecumenism as humanistic project with the evangelical and Orthodox ecumenism as the God-human endeavor. In other words, for Saint Justin, as a result of the dwarfing of the God-man Christ by man, first by the infallible man in Rome, and later by infallible human beings all over Europe, Christianity in the West has been reduced to humanism.”27 Here we find clearly recognized and elaborated Bishop Nikolai’s aforementioned critique of a European civilization separated from Christ on the one hand, and of the presence of the secularist tendencies inside the Church on the other. According to St. Justin, in both Roman Catholicism and Protestantism man as the supreme value replaces the God-man Christ.

But his criticism is also addressed to the Orthodox whose humanistic theorems regarding the plans for a next ‘ecumenical’ Council of the Orthodox Church have almost nothing in common with the “essential relation to the spiritual life and experience of apostolic Orthodoxy down the ages.”28 We can only wonder if such a spirit was present in

the preparation of such an important event for the Orthodox Church, what it was in her relations to everything else she should care of and deal with. In one of his early works The Inward Mission of Our Church: Bringing About Orthodoxy, he underlines that:

“The mission of the Church, given by Christ and put into practice by the Holy Fathers, is this: that in the soul of our people be planted and cultivated a sense and awareness that every member of the Orthodox Church is a Catholic Person, a person who is for ever and ever; that each person is Christ’s, and is therefore a brother to every human being, a ministering servant to all men and all created things. This is the Christ-given objective of the Church. (…) For our local Church to be the Church of Christ, the Church Catholic, this objective must be brought about continuously among our people. And yet what are the means of accomplishing this God-man objective? Once again, the means are themselves God-man because a God-man objective can only be brought about exclusively by God-man means, never by human ones or by any others. It is on this point that the Church differs radically from anything that is human or of this earth.”29

Yet at the beginning of the above-mentioned book on ecumenism Fr. Justin wrote: “Ecumenism is a movement that swarms with numerous questions. And all of these questions, in fact, spring from a desire and emerge into a desire. And that desire wants one thing: the True Church of Christ. And the True Church of Christ holds, and must hold, answers for all questions and sub-questions that ecumenism raises. Because, if the Church of Christ can not resolve eternal questions of the human spirit, then she is not necessary… Among the creatures man is the most complex and most mysterious one. That is why God came down to earth and became a man… With this reason he remained on earth in His Church, which He is the head, and she—His Body. She—the True Church of Christ, the Orthodox Church: and in it all the God-man with all his benedictions, with all its perfections.”30

By this Fr. Justin shows that the unique God-man event and reality that is the Church = Christ is the salvation for all modern ecumenical enquiry and wandering and is, at the same time, the only hope of fallen humanity and the world.

This vision of ecumenism is especially developed in his Notes on ecumenism, dating from 1972 but only published in 2010. Bishop Athanasius (Yevtic), thanks to whose efforts the Notes were published, explains how they were formed at a time when Justin Popovic was working on his book The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism.31 He observes that Notes on ecumenism shows all the breadth and depth of Justin Popovic’s theology and ecclesiology founded on the very sources of Orthodoxy. “In these Notes the real Justin is present: by his language, by his style, literature, polemics, philosophy, theology, and above all, by his confession of the God-man Christ and His Church.”32

For developing his understanding of the “Orthodox ecumenism”, as we can read in these Notes, Justin Popovic do not refers to any secondary literature of his time but invokes the help of the testified experience of the Scripture and the living Tradition preserved in the Church of Christ. However, methodologically speaking it may represent a kind of lack in Justin’s approach of Western Christianity, as Bishop Maxim (Vasiljevic) noted. Justin’s methodology was based on the communion with the incarnated historical God-man as he noted:33 “‘Gospel not according to man’ (Galatians 1:11). There is nothing ‘according to man’: neither content, nor method; since nothing can be measured by man nor ‘according to man’. Everything (should be) in accordance with the God-man: therefore—(it is) irreducible to humanism or its methods, but everything (should be measured) according to the God-man and man through the God-man.”34

This does not mean that Fr. Justin was against a thorough work on contemporary theological or any other scholarship, on the contrary, but for this it was essential first to be formed at the school of the Church of Christ in order to obtain the mind of Christ (1 Corinthians 2:16).35 But to “obtain the mind of Christ” and to come to the Truth the first thing that has to be done is repentance, “Repentance leading to knowledge of the truth” (2 Timothy 2:25).36 Only then will the Truth, which is Christ God-man Himself, be given for the faith, as Saint Paul stated: first faith, then truth, and at the end love, which is the bond of perfection (Colossians 3:14). From this it becomes apparent that ecumenical dialogue cannot be only a dialogue of love.37 “Faith is the bearer of truth and Love loves because of the Truth; what was delivered from a lie—deception, love? ‘Love speaking the truth’ (Ephesians 6:15) ‘new’ love: Christ—the God-man: delivers from sins, death, from every evil, from every devil: And it is capable of being eternal because it loves what is eternal in man, above all: The Eternal Truth.”38

After this first important remark, we may proceed by saying that Justin Popovic in his Notes elaborates his concept of ecumenism on a central difference between any humanistic ecumenism on the one side, and the “Orthodox ecumenism” on the other.

The main problem of the modern European man, according to Justin Popovic, is that he fights against the God-man, and in that fight he degenerates himself into a pseudo-man.39 What is the cause of this fight? Long patristic tradition gave a comprehensive answer to this important anthropological question, which was summarized by Fr. Justin in his Notes by these words: “For only by solving the problem of the God-man, would the problem of man be solved, and also the problem of everything eternal in all human worlds. Therefore: God always has to be in the first place and a criterion for everything, and man should always be in the second place. From God to man: from the God-man to man. The first commandment, and always the first: love of God (theofilia), and from it and after it, the second commandment, always the second (Matthew 22:37-39). And all the humanism headed by popes, goes the other way around.”40 This leads him to conclude that in comparison to all other heresies, humanistic ecumenism is a “pan-heresy”.41

The reason for this, according to Fr. Justin, is that humanistic ecumenism falls into the trap of scholasticism and rationalism, which want to measure all and explain all by man and only “according to man”. And the main problem is that they are guided only by the unquenchable desire to “‘conquer’ this visible, material world, so as Fr. Justin noticed: “They live by it and they live for the sake of it: every culture is in this and for this, and so is civilization. And what would be the content of man even if he ‘gained’ the whole world, all the worlds (Matthew 16:26)/?/ (…) What is the use of it if by it and because of it, man forfeits his soul which possesses his entire and eternal value, joy and the meaning of his being?”42 That is why every human work and all human achievements should be viewed from this principal theanthropic criterion, which is the God-man. The very reason for this is that “He alone heals and saves man from humanistic selfishness, narrowness, goal and closing in oneself”.43 In other words, He only can satisfy the unquenchable human desire for life without end. This is also the reason why the Church is principally the Divine Liturgy, and not a worldly or social organization.44

Now it becomes clear that, as Saint Justin said, the problem of ecumenism presupposes the genuine Church. So, by answering the question of the genuine Church we should be able, at the same time, to give a proper answer to ecumenism.45 Then what is the Church? According to Fr. Justin, “the Church is the most complex organism in all the worlds; it comprises everything from all the worlds: that is why it is impossible to give an integral definition of the Church. Thus her most perfect definition is the God-man and He is her ineffable essence. The God-man embraces everything: from God to atoms. Everything is in God although everything is not God: it is precisely by Him and in Him that everything stays personal, original, on its own: in being and in essence and above all, in personality. For personality is the most mysterious mystery after God himself.”46

From this very important passage we can draw several conclusions about Saint Justin's understanding of Orthodox ecumenism:

-

the perfect definition of the Church is God-man Himself, as “her ineffable essence”. This is also the reason why he so often insists on the fact that for a proper understanding of ecumenism, and consequently of the Church, the key is to properly comprehend and perceive the God-man Christ and His work.47

In “the very personhood of the God-man, our Lord Christ, in the Second Hypostasis of the Triune Godhead, is the whole divine and whole human nature. Perichoresis /= interpenetration/-through faith, the holy sacraments and virtues.”48 Ecumenism founded on the God-man becomes “ontologically integral, temporally integral, eternally integral, integral by the Truth. And it is only the God-man who unites everything and everyone in the Church.”49 By the fact that He is a Man, He united to Himself the whole creation, and by the fact that He is at the same time God, He united to Himself everything and all except the sin, death and the devil. And so “the God-man by the Holy Spirit through the Holy Sacraments and holy virtues performs human salvation.”50 Thanks to the theanthropic humanism, the “man spreads out through all theanthropic dimensions. And all his capacities and components do so. Everything acquires its theanthropic eternity through (the) victory over death, sin and the devil.”51

And finally, according to Fr. Justin, and with this we will finish with this brief presentation of his understanding of ecumenism; though much remains to be said, that goes far beyond the limits of this presentation.52 “God-manhood is the fundamental catholicity of the Church (=ecumenicity, the same as the relation between the atom and the planet53): to the Trinity: but by the God-man who introduces and unites with the Holy Trinity who is the ideal and the reality of the perfect catholicity (=ecumenism): the ideal society and the ideal person: everything is perichoresis: everything perfectly united and preserved in that perfect catholicity. Every man is a living image—an icon of the Holy Trinity = therefore the Church as the ‘body of the Holy Trinity’ is everything and all for him and his trinitarization (being filled with the Holy Trinity)’ represents ‘human perfection’—in the God-man. That is why the Church is the most perfect workshop for making a perfect man. Everything else apart from the God-man: pseudosociety and pseudopersonalities are an illusory humanistic mixture of everything. Only Christ is everything and everyone.”54

As we can see, the life path of Bishop Nikolai was a dramatic one; it was a path of organic maturation. His life experience and the experience of Fr. Justin Popovic were in their depths the same; nonetheless, the journey of Fr. Justin was different from the journey of his teacher Bishop Nikolai. It is possible that Fr. Justin’s journey was different precisely because Bishop Nikolai’s preceded it. Bishop Nikolai was the first to tackle his drama and the existential crucifixions of himself and his time; he suffered through and experienced, in his own skin, the tragedy, doubt, and divisions of his era, for the sake of Fr. Justin and for many of his other contemporaries. That is why Fr. Justin, even from his first writings, showed a stable and unwavering faith, and why he was crystal clear in bearing witness and giving testimony, and remained so to the end of his life. His path was not ascending and gradual as was Bishop Nikolai’s; rather, it was a descent into the depths. That which he started, he only built upon.55

In conclusion we can say that such an “ecumenism” (from the Greek word oecumène, universe) would reflect conciliar and soteriological responsibility of the Church for the salvation of the entire world. We hope together with Saint Nikolai Velimirovic and Saint Justin Popovic to be representatives of and witnesses to an ecumenism that is not against dialogue, testimony or collaboration, but against all kinds of falsifications and errors. Thus discernment of spirits is a principle that applies perfectly to the ecumenical movement.

It is unfortunate that many are trying to equate and substitute the MISSION or preaching Christ to every corner of the ecumene (=world) with the word "orthodox (sic.) ecumenism".

This attempt at rehabilitating the word ecumenism and give it orthodox meaning is to muddle the clear waters of Orthodoxy. It is, in my opinion, an attempt to justify Orthodox participation in WCC and endless purposeless theological dialogues with the heretics. Saints, bishop Nikolai and especially father Justin spoke and wrote unequivocally and clearly that ecumenism is a heresy, pan-heresy. Any attempt, even by bishop Atanasije (Jevtic), to speak of "orthodox ecumenism" fails at once when one has the published writings of St Justin in his hands. Will it be that one day we may be confronted with "orthodox Arianism" just like we have been with "orthodox Darwinism" "orthodox mono/mia physitism" etc.?? God forbid!

Dionissios S.