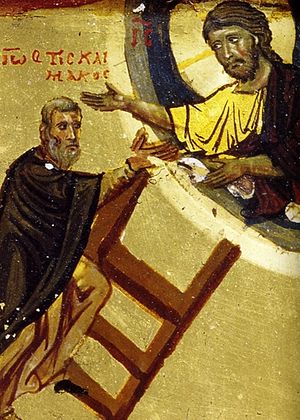

The sixth step of St. John Climacus’s The Ladder of Divine Ascent is dedicated to the spiritual discipline of the remembrance of death, which is to have in mind the hour of one’s repose and the following judgment before God, in order to deter oneself from sin. St. John tells us that the remembrance of death is the highest work for one who is spiritually minded (6:4), and that “He who has mounted [this sixth step] will never sin again” (6:24), echoing a passage from The Wisdom of Sirach: Whatsoever thou takest in hand, remember the end, and thou shalt never do amiss. (7:36). This teaching is quite pervasive in our Orthodox Tradition and can be found in the counsels and works of many major Fathers. According to Abba Dorotheos of Gaza, upon death our soul will remember every sin we ever committed, which is a horrible and terrifying thought! And thus to meditate upon this moment when all of our transgressions will come flooding back to us is a great aid in battling temptation and avoiding sin. In fact, St. John teaches that to live devoutly we must view every day as our last (6:24).

This is an especially relevant teaching for our times, because our world is far from understanding death, and we seem to have a schizophrenic manner of interpreting it. On the one hand, we have embraced death as something natural and good. No longer is death the last enemy to be overthrown, but through the naturalistic evolutionary philosophies that completely dominate every aspect of our lives we have been forced into the conclusion that death has always existed, and thus is a creation of God, and thus it is good. Of course, Church Tradition teaches that God does not desire the death of anything living and that the current state of creation is due to fall of Adam and Eve. Modern saints have uniformly rejected the theory of evolution—St. Nektarios says it is akin to mythology, St. Barsanuphius of Optina says it is a bestial philosophy, and St. Paisios calls it blasphemy. Since we see death as something good, we do not feel the need to prepare for it, and so when we say “live like you were dying” we usually mean to do something ridiculous and crazy that you would not normally do, but Orthodoxy teaches us that before dying we need to repent. Unfortunately we have either completely missed this message, or failed to take it seriously in our modern culture.

On the other hand, the world is dedicated to the avoidance of death—we go to school so we can get a decent job so we can provide food, shelter, clothing, and medicine for ourselves and our families so that we may delay death. When we get older we have surgery to look younger, and when our relatives do get old and sick we hide them away in a home, or euthanize them to avoid dealing with the clear signs of impending death. We even fill our lives with empty entertainments to distract our minds from the harsh reality that we suffer, and we will die, but these distractions only cause us to truly die a spiritual death.

Fortunately, we have daily Church services, and especially the Divine Liturgy, which is the greatest help in drawing nearer to God. I think it could even be said that we receive Holy Communion because we remember death. In 1 Corinthians 11:26 St. Paul tells us that in celebrating the Eucharist we are proclaiming Christ’s death, and through His death we hope to enter eternity free from the passions and filled with love for God. Thus we pray before communing, “grant me until my last breath to receive without condemnation the portion of Thy Holy Things, unto communion with the Holy Spirit, as a provision for life eternal, for an acceptable defense at Thy dread judgment seat; so that I also, with all Thine elect, may become a partaker of Thine incorruptible blessings” (St. Basil the Great).

The remembrance of death deters us from all sin because it is a devotion of humility and repentance. Remembrance of death is more than simply looking ahead to our repose—it is the acknowledgment that our entire lives and the entire creation are tainted with death, fallen from the Paradise that God gave man to tend. There is no true joy in the things of this life because there is a lurking death behind them all, and every time we sin we drag the world further into death. To truly live this “charismatic despair” is a gift of grace that calls us to repentance. The Scriptures and the Holy Fathers teach that the fate of the creation is tied to that of man, and thus our repentance and our redemption is the redemption of the entire cosmos, made possible by the Incarnation, Crucifixion and Resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. Christ humbled Himself, becoming as one of us, and He descended into the depths of Hades before again ascending to His heavenly throne. We are called to place ourselves in this path of Christ—to divest ourselves of the interests of the flesh, humbling ourselves and recognizing our self-made mortality, thereby ascending to the heights of deification and restoring the entire cosmos to its former state of incorruption. But again, it is one thing to know this teaching, and another to truly live it. Remembrance of death, and repentance, are hard, and sometimes it takes years of struggle to begin to see some real fruit, whereas the pleasures of the world lure us in with the promise of instant gratification, but lead ultimately to the death of the soul rather than death to the flesh and the world.

To resist the instant pleasures of the world and to have death in front of us at all times we need to deeply enter into the life of the Church—Her services, prayers, sacraments, and asceticism. The life of the Church is the life of Christ, and He led a perfect life of remembrance of death. In His infancy, St. Simeon prophesied that the Christ Child is set for the fall (Luke 2:34), and His public ministry culminated in His self-sacrificial death on the Cross, which He foretold to His disciples many times. Likewise, the Church places death in front of us at all times—our day is even “book-ended” with death. The first thing we do when we wake up in the morning is to Cross ourselves—bless ourselves with the death, and resurrection of the Lord. Fr. Thomas Hopko preached that when we wake up we should say to ourselves “Christ, Cross, commandments”—call to mind (and heart) Christ Who died for us, the Cross on which He died and which we must take up in our daily lives, and the commandments which require us to die to ourselves daily. And before retiring to sleep, we point at our bed and pray “"Behold, the coffin lieth before me; behold, death confronteth me. I fear, O Lord, Thy judgment and the endless torments” (St. John of Damascus). Even sleep, belonging to the fallen world, is an image of death. St. John continues, “yet I cease not to do evil,” and unless we repent of our evil our bed becomes truly a coffin for our deadened soul.

St. John Climacus teaches that “the remembrance of death is a daily death” (6:2), and “A true sign of those who are mindful of death in the depth of their being is a … complete renunciation of their own will” (6:6). This “daily death” is precisely the picking up of the Cross, the following of the commandments, and the focus on Christ to which Fr. Hopko calls us. Fighting against our passions, which is dying daily, causes us suffering, as we love our sins in our fallen nature and want to cling to them, but in Orthodoxy we understand that Christ came not to wipe away our suffering, but to fill it with His presence, and thus it is salvific. Just as St. John says we must be mindful of death from the depth of our being, so suffering teaches us to find our heart, the depth of our being, because the presence of suffering is a witness to the existence of our heart. Unless our faith enters our heart it is ultimately in vain.

Dr. Christopher Veniamin offers us a profitable word on the daily death of the Christian, speaking of that which he undoubtedly saw in his own spiritual father, Elder Sophrony:

We see in the lives of the saints, these are people who are ready to die. And they're not just ready to die, they prefer to die than to grieve God, than to lose grace, than to suffer even a diminution of grace. When you are struggling against the passions, you see that the passion will always have a hold on you, until you're willing to die rather than to commit the sin that the passion suggests. That's why the Christian life is a martyric life. We die daily.

There is an efficacy to suffering, in that, with the right disposition, it helps us to find our spiritual heart, from which, once it is awakened, we can truly call out to God in the fullest sense, and truly invite Him to enter and enlargen our heart. Easy lives with minimal suffering contribute to the hiding of the heart. Through our baptism into the Church we have put on Christ’s death and Resurrection, have been born again, and thus the path to God is wide-open, but it remains a struggle. For instance, we may try to keep a disciplined morning and evening prayer rule, but being so groomed on instant gratifications we are easily discouraged at not seeing any change in ourselves and so it becomes easier and easier not to pray, with part of ourselves thinking that prayer does not really work. The lives of the saints who successfully repented from the depths of their hearts are of course encouraging, but eventually the experience to which they witness must become our own personal experience in order to stay on the path. So this is our daily struggle—to devote ourselves to Christ more every day, and to orient all that we learn towards experiential knowledge of God—to finding our hearts and calling out to God from that deepest part of our being. But we can do none of this on our own, but only by the grace of God in His Church.

The remembrance of death, as propounded by St. John Climacus in the sixth step of his Ladder of Divine Ascent, and countless other saints, is central to the Orthodox Christian life. To remember the hour of our repose and the dread judgment seat of Christ is to inspire repentance and pulling away from the pleasures of the world which are tainted with the death brought upon the world through the sin of Adam and Eve. St. Gregory Palamas teaches that repentance is the beginning, middle, and end of the Christian life, and accordingly, the Church places death and repentance before us every day. Most of us accept the truth of this spiritual teaching and practice without question, but the struggle to place it in our hearts remains a process. It is true that any day could be our last, but our world’s distorted understanding of death, and firstly our own pride, prevent us from preparing for death and for meeting Christ. But we are called to struggle and despair not, and so, by the grace of God and the prayers of all His saints may we ever press forward.