In an Orthodox church there is no thing or action which does not carry meaning of spiritual weight. Even the iconostasis and curtain over the Royal Doors are full-fledged “participants” in the Divine services.

What is the significance of the iconostasis and curtain in the microcosm of an Orthodox church?

The architecture and interior decoration of an Orthodox church is, if it can be so expressed, heaven on earth. It is a model of the spiritual world—of the Heavenly Kingdom—which the Lord opened to us through the holy prophet Moses on Mt. Sinai. Then God commanded to build the Old Testament Tabernacle according to the precise pattern given by Him to Moses, down to the smallest detail. New Testament Orthodox churches have the same arrangement as that of the Old Testament, but with the difference that our Lord Jesus Christ became incarnate and completed the work of the salvation of mankind. It is namely from this monumental event that there are changes to New Testament temples in relation to that of the Old Testament.

But there remained an immutable three-part structure to churches. According to the holy prophet Moses it includes the courtyard, the sanctuary, and the Holy of Holies. In the New Testament church it is the narthex, nave, and altar.

The narthex and nave themselves symbolize the earthly Church. Any believing Orthodox Christian can be in these parts. The nave correspond to the Old Testament sanctuary. Earlier no one but priests could be found there, but today, because the Lord with His most-pure blood cleansed us all and united us in His Mystery of Baptism, the nave—the New Testament sanctuary—is open to all Orthodox Christians.

The Holy of Holies of the Mosaic Temple corresponds to the altar in the New Testament Church. It symbolizes the Heavenly Kingdom. It is not without reason that it is elevated in relation to the nave and narthex. The very word “altus” in translation from Latin means “high.” The center of the altar is the altar able. It is this throne[1] on which God Himself sits invisibly in the church. It is the main place of the Orthodox temple. Even the clergy, without a special need (such as to celebrate a service) and the necessary liturgical clothing (such as the cassock) must not touch it—it is holy ground—the place of the Lord.

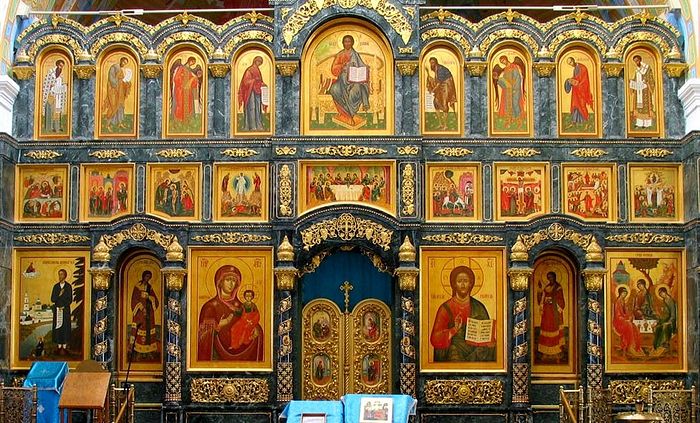

Usually between the altar and the nave there is erected a special wall, adorned with icons, known as the “iconostasis.” It is a compound Greek word formed from the words for “icon” and “to stand.” This partition is not erected, as some incorrectly think, to conceal what the priest is doing in the altar. Of course not. The iconostasis has a quite distinct liturgical and spiritual significance.

The practice of erecting an iconostasis is quite ancient. According to Church Tradition the first to order the closing of the altar by a curtain was the Holy Hierarch Basil the Great in the second half of the fourth century. But even earlier there were well-known partitions between the altar and nave was already a part of the church, for example in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

The modern appearance of the iconostasis was basically developed in Church art by the beginning of the fifteenth century.

So, what does the iconostasis mean in the spiritual and liturgical sense?

It itself symbolizes the world of saints and angels—the Heavenly Kingdom, to us not yet fully attainable. It is that place and condition of soul to which we must aspire. The Heavenly Kingdom for us, living on earth, is yet separate and inaccessible. But every Orthodox Christian is obliged to move towards to it and strive with the help of those salvific means which the Church and its Head—Christ—offer us.

The visual separation of the altar from the nave should motivate us to strive in that direction—to the heavenly, and this aspiration is the core of the life of every Orthodox Christian. We believe that the merciful Lord will once open to us the door to Paradise and lead us in, as a loving Father His children…

From another side, the icons of the iconostasis tell us the story of the salvation of mankind by our Lord Jesus Christ. For example, the iconostasis can be single or multi-tiered. On the first tier In the middle of the first tier is the Royal Doors, which is also the place of God. Even the priest doesn’t have the right to pass through them: only in vestments and at strictly specific times of the services. On the right and the left are found the so-called deacon’s doors, through which clergy and altar servers can enter into the altar. They are called “deacon’s” because the deacon leaves the altar through them and returns again during the reciting of special prayers (litanies) through the Royal Doors. On the right of the Royal Doors is hung the icon of the Savior, and on the left of the Most Holy Theotokos, and on the deacon’s doors, as a rule, icons of the holy Archangels Michael and Gabriel—those heavenly deacons of God, or the holy deacons the Proto-Martyr and Archdeacon Stephen and the martyred Lawrence. Rarely there are other icons. Next to the right deacon door is the icon of the parish’s feast.

If there is a second tier on the iconostasis it is known as the “Deesis,” which in translation from Greek means “supplication” or “petition.” In the center of the row is the image of Christ the Pantocrator enthroned, to His right the Most Holy Theotokos in a prayerful pose, and to His left the holy Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist of the Lord John, also with prayerfully outstretched arms. Next are icons of various saints also in prayerful poses, turning to the Savior. These can be various saints of the Orthodox Church but most often it’s the Twelve Apostles.

Immediately above the Royal Doors is placed an icon of the Mystical Supper—the first Liturgy, celebrated by God Himself. It is a symbol of the most important ministry of the Church and church—the service of the Holy Eucharist—the Body and Blood of Christ.

If there is a third tier on the iconostasis then on it are placed icons of the Twelve Great Feasts. They symbolize the salvation by Christ of fallen mankind. Less often (only in major cathedrals) are there fourth and fifth rows. In the fourth row are depicted the holy prophets, and in the fifth the forefathers (the Holy Forefathers Adam and Eve, the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and so on). In the center of the top row of the iconostasis is placed an icon of the Holy Trinity, crowned by the Holy Cross as the main instrument of our salvation.

In the Church the curtain is known by the Greek word “καταπέτασμα (katapetasma).” It divides the Royal Doors on the altar side from the holy altar table.

Everything in the Church, including the Royal Doors and curtain, has a strictly defined meaning.

For example, the Royal Doors are, if it may be so expressed, the door of Christ. Therefore on them are often placed the rounded icons of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos and the four holy Evangelists—proclaiming the good news of the God-Man Christ. The opening of the Royal Doors in the services and the priests’ passing through them is a symbol that the Lord is present in the church and blesses those worshiping.

An example:

The beginning of the All-Night Vigil: After the Ninth Hour the Royal Doors are opened and the priest silently censes, then proclaiming before the altar the doxology to the Holy Trinity and the other prescribed prayers, then exiting from the altar through the Royal Doors to cense the entire church, icons, and worshipers. This all symbolizes the beginning of sacred history and the creation of the world and mankind. The priest censing the altar and those at prayer symbolizes that God dwelt in Paradise with man and they directly and visibly communicated with Him. After the censing the Royal Doors are closed, representing the Fall of man and his expulsion from Paradise. The Doors are again opened at the Little Entrance with the censer in Vespers—it is the promise of God to not abandon sinful man, but to send to him His Only-Begotten Son for his salvation.

It is precisely the same at Liturgy. The Royal Doors are opened before the Little Entrance as a symbol of Christ’s beginning to preach, because after that a bit later is read the Epistle and Gospel. The Great Entrance is with the chalice and diskos—the Savior’s going to His suffering on the Cross.

The closing of the curtain before the exclamation “Let us attend. Holy things are for the holy” is a symbol of the death of Christ, the placing of His Body in the tomb and the sealing of His tomb with a rock.

As an example, many Great Lenten services are served not only with closed Royal Doors, but with a closed curtain as well. It’s a symbol of man’s expulsion from Paradise, that we must now weep and lament over our sins before the closed entrance to the Heavenly Kingdom.

The opening of the curtain and the Royal Doors during the Paschal service is a symbol of the restoration of the lost communion with God, the victory of Christ over the devil, death and sin, and the opening of the path to the Heavenly Kingdom for every one of us.

It all speaks to us about that in our Orthodox services and in the structure of the churches there is nothing superfluous, but everything is coherent, harmonious and intended to guide Orthodox Christians into the Heavenly realm.

I read with great joy your article on the iconostasis and wanted to make a few comments.

In 2012 with co-author Val Rajic I wrote and published the book, Serbia: Faces & Places. While in Serbia taking pictures for the book I of course visited numerous Serbian Orthodox churches. I was somewhat shocked when visiting a number of churches that they had no iconostasis. After publishing the book I had the great pleasure of hearing a presentation by the Abbot Hilandar on Mt. Athos, I also published a book on Hilandar.

My concern is that we is in some kind of silent process in the Serbian Orthodox church to revise the interior of our churches to resemble those of other faiths. I am concerned that this is some Ecumenical effort to change our religious practices to look like other Christian churches. I have noticed in my own Cathedral the curtain in the alter is no longer used and the doors remain open throughout the service...I am concerned about this "new" practice.

William Dorich, Publisher

You can see images from my book at www.serbiafacesandplaces.com