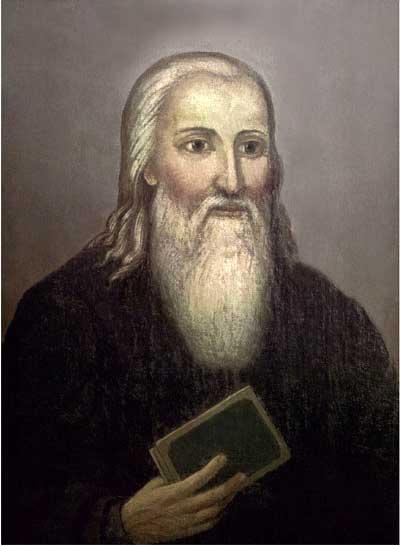

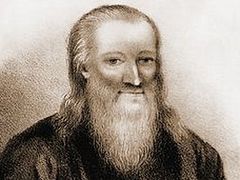

St. Zosima (Verkhovsky) (1767-1833) was one of three sons in a large family born to a noble family in Smolensk province. His father was the governor of Smolensk. The family was very pious in their Orthodox Christian faith, and when the three young men lost their father, their mother had them divide their substantial inheritance while she was still alive. Their sisters having already received their inheritance, the three brothers were left to divide the estate amongst themselves, at their mother’s blessing. In the peaceful process of dividing the estate, the brothers argued over only one thing: Each wanted to take their father’s debt upon himself.

Eventually the youngest of the brothers, future elder, Zachary in the world, left his portion to his siblings and resolved to become a monk. He became the disciple of Elder Basilisk, a hermit laboring in asceticism in the Bryansk forest, which is not far from Smolensk. When Zachary arrived at the hermitage, the fathers there counseled him: “You would be truly blessed, O good youth, if Father Basilisk would agree to take you as a disciple. He is our desert star; he is an example to us all. Truly God's mercy would be upon you if he would agree to this, for although many of us have begged and tried to persuade him to be our teacher, having true humility he has firmly refused everyone, saying that he is an unenlightened ignoramus and can be an instructor to no one. He added that he himself leads such a wretched and feeble existence that he would certainly be of benefit to no one. Furthermore, he prefers to live in complete silence and to be always alone with God.”[1] The elder did not refuse Zachary, and the latter humbled himself and became a true disciple and monk. Later the two monks, elder and disciple, travelled to Siberia and became hesychastic “desert dwellers”—their desert being the impenetrable wilds of Siberia.

Although after years of the solitary life, Elder Zosima became a guide of women monastics and founded a convent for his spiritual daughters in sparsely inhabited region south of Moscow, he became a true “scholar by experience” of eremitic monasticism, and in his letters to disciples he has left us a description of this life. Although most holy men and women of the latter times unanimously agree that this way of life is scarcely possible for monastic aspirants now, because people are simply too weak in their faith, we can still admire and sigh when read about this exalted way of life, and feel contrition for our inability to live it.

Here are Fr. Zosima’s words about why he chose the desert life:

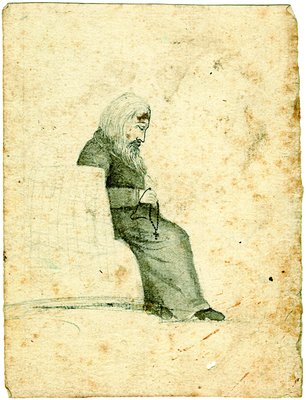

St. Zosima (Verkhovsky), drawing, 1820s-30s. From Widipedia. The inner desert, I trust, will be a teacher leading one to spiritual advancement. There are no comforts there, as in the world, with which the soul might busily preoccupy itself; there is no need for excessive handiwork, and there is no one to visit for entertainment or idle conversation. You would have no visitors with whom you might share a comforting and fine meal except for your disciple (or a pilgrim) with whom you would eat only the strictest fast food. One must suffer the horror of demons, and the loneliness and languishing of daily and continuous confinement and seclusion. The fear of death settles continuously in one’s soul, frightening it with thoughts of being attacked and possibly killed by animals, snakes, and evil people. One suffers extreme need in everything, dire poverty, and lack of the most essential things, living in a meager hut which has nothing in it save a few books, which are one’s only joy and consolation. One hears neither of his friends and how they live, nor of the health of relatives, nor of his loved ones. All the pleasures of his past life have departed. In a word, he has died to the world, and the world to him. There is nothing temporal over which to rejoice, thus darkening the mind, drawing it away from God. The whole mind, reason, memory and feelings, the whole person, is immersed in God, ascending to Him through the contemplation and vision of His wisdom, His greatness, and His Providence in His works. Heaven and earth are as two constantly open books before him in which he reads of the greatness and wisdom of our God. To Him alone he weeps day and night, prostrating himself in supplication, begging to be strengthened and preserved till the end of his days in this way of life, the demands of which exceed his strength, but which he nevertheless undertook for God’s sake…

St. Zosima (Verkhovsky), drawing, 1820s-30s. From Widipedia. The inner desert, I trust, will be a teacher leading one to spiritual advancement. There are no comforts there, as in the world, with which the soul might busily preoccupy itself; there is no need for excessive handiwork, and there is no one to visit for entertainment or idle conversation. You would have no visitors with whom you might share a comforting and fine meal except for your disciple (or a pilgrim) with whom you would eat only the strictest fast food. One must suffer the horror of demons, and the loneliness and languishing of daily and continuous confinement and seclusion. The fear of death settles continuously in one’s soul, frightening it with thoughts of being attacked and possibly killed by animals, snakes, and evil people. One suffers extreme need in everything, dire poverty, and lack of the most essential things, living in a meager hut which has nothing in it save a few books, which are one’s only joy and consolation. One hears neither of his friends and how they live, nor of the health of relatives, nor of his loved ones. All the pleasures of his past life have departed. In a word, he has died to the world, and the world to him. There is nothing temporal over which to rejoice, thus darkening the mind, drawing it away from God. The whole mind, reason, memory and feelings, the whole person, is immersed in God, ascending to Him through the contemplation and vision of His wisdom, His greatness, and His Providence in His works. Heaven and earth are as two constantly open books before him in which he reads of the greatness and wisdom of our God. To Him alone he weeps day and night, prostrating himself in supplication, begging to be strengthened and preserved till the end of his days in this way of life, the demands of which exceed his strength, but which he nevertheless undertook for God’s sake…

Thus it seems to me that by fleeing all that weakens one and leaving for the inner desert, one might grow spiritually through the help and grace of Christ. This is especially true if one begins to struggle in asceticism, no longer having anyone nearby to envy him, nor anyone to move him to feelings of pride and self-love with their praise. And God Who seeth in secret shall reward him openly at His Second Coming. And if—God forbid!—one should continue his wicked and careless way of life, he will at least only have to answer to God for himself and for his own wretchedness. He will not be held responsible for the sins of others, since he did not lead anyone to sin and weakness of spirit, as often happens with those who lead a life of debauchery amidst many people.

However, I believe that if one departs for the inner desert overcome and persuaded by a divine love for Christ, he will truly live as if in Paradise. No longer hindered by any obstacles, he will be free to delight constantly in the thought of God and in sweet prayer of the heart and mind, with God and in his God. No longer shedding tears of grief alone, but weeping in joyful sorrow, he will dwell in the mountain heights as a heavenly bird, offering sweet songs to his Creator and Redeemer. Separated from all persons and things, as a beloved lamb of Christ, he will graze and take his fill in joy of the heart through the grace of Christ. Indeed, such a person would not trade his desert life for royal chambers that require excessive care, for living this way he may constantly contemplate the Kingdom of Heaven with ease. Nor would he desire any gold, precious stones or pearls, for he has Christ, the most precious of stones, alive within him, pacifying, gladdening, comforting and preserving him from all evil.[2]

Not only saints came to the desert seeking a life of peaceful silence, but even sinners as well came to seek repentance in the holy desert, which renews men and makes great saints of them. I am referring to those like St. Mary of Egypt, and the holy father, a weaver by trade, who, having committed adultery with a nun, saw himself approaching complete ruin and fled to the refuge of the desert, which raised him to sanctity and entrusted him to Christ God as worthy of eternally reigning with Him. Such examples cause me, a great sinner, to dare to partake of the desert life, hoping that perhaps the Lord in His mercy will forgive me, my father, for the sake of your holy prayers.[3]

Such a life leads one to repentance in many ways; but if I persist in my being harder than a stone, and if I neither yield worthy fruits of repentance nor obtain God’s mercy, I will at least avoid sin, with God’s help, by living in the desert which has none of the sensuous attractions that cause one to fall so easily. For if one has not yet attained to dispassion and has no great spiritual strength, I think it better for him to depart humbly and to live a life without good deeds in the inner desert, avoiding those things which cause him to fall, rather than to seek great salvation amidst the waves of the world which cast one into sin if he has not the grace nor strength to resist sin and to defeat its constant passionate onslaught.[4]