Venerable Columba (also Colum Cille, Colm Cille), whose name means “dove”, is perhaps the greatest of all Celtic saints. This man of God was born in the year 521 and reposed in the Lord on June 9, 597. The founder of the great and famous monastery on Iona along with numerous other monastic communities and churches, St. Columba has for fourteen centuries been greatly venerated by many Christians as the enlightener of Scotland, a co-patron of Ireland (on a par with Sts. Patrick and Brigid) and the spiritual father of a host of churches throughout Europe.

We have a very trustworthy and detailed account of the life, achievements, miracles, visions and prophecies of this celebrated saint in the work called The Life of Saint Columba, written in Latin at the turn of the seventh century by the Venerable Adomnan, the ninth abbot of Iona, who is a much venerated saint himself. There were numerous later biographies of Columba, written before and after the Norman Conquest, with varying degrees of authenticity. He is praised in the work A Miracle of Colum Cille, composed at the beginning of the seventh century, and other early works. The Venerable Bede of Jarrow wrote about St. Columba, among other saints, in his History of the English Church and People. The Irish saint named Dallan Forgaill, who for part of his life was blind, composed “The Eulogy to Saint Columba”. A great number of traditions related to the name of Columba exist in Irish and Scottish Gaelic folklore.

The future saint was descended from the kin of Cinel Conaill, a branch of the ruling O’Neill Dynasty in Ireland. His parents’ names were Fedlimid and Eithne. Notably, his mother Eithne was locally venerated as a saint. She was buried on the isle referred to in early sources as “Hinba”, which has not yet been identified. Most historians suggest it is the uninhabited isle of Eileach an Naoimh (meaning “Holy Island”) in the Inner Hebrides, situated to the west of Scotland between Mull and Argyll. This isle boasts several beehive-cells, chapels, crosses, an underground storeroom and the graveyard of an Irish monastery, probably founded by St. Brendan of Clonfert (“the Navigator”) as early as the 530s. If this can be confirmed, then it is the oldest surviving church construction in Britain. The supposed grave of Eithne is marked there.

Shortly before Columba’s birth his mother had a prophetic dream: An angel first gave her a splendid tunic and then took it back and stretched it out over the earth. The holy man of God was born in Gartan in what is now County Donegal, and it was by the command of an angel that he was given the name “Columba” signifying his dove-like simplicity and meekness. It was clear from his infancy that the saint of God was destined to serve the Church. He was raised in chastity by the presbyter and tutor Cruithnechan, living at the church from childhood. Afterwards Columba, like other outstanding saints of the Irish Church known as the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland”, studied at the Monastery of Clonard under its founder, the holy abbot Finnian. According to some traditions, he may also have studied at Moville Monastery, founded by St. Finnian of Moville. It was at Clonard in 551 that he was ordained priest. In the year 546 the venerable man founded a church and monastery at Daire, which is now spelled Derry (now in County Derry). The foundation of the Irish monasteries of Durrow (in 556 in Offaly), Kells (in County Meath) and Swords (County Fingal; a holy well that gushed forth there in Columba’s times still exists) is traditionally attributed to him. The venerable man dedicated all his energies to the establishment and consolidation of the Church in Ireland and Scotland.

In 563 (according to another version, in 565) Columba, accompanied by twelve disciples, left Ireland forever and sailed to Scotland for the preaching of the Holy Gospel. There are a number of later traditions explaining his motives for leaving his motherland. They claim that he did it as a voluntary exile for Christ’s sake; or for supporting his Irish compatriots living in the northwestern part of Scotland (who had founded a colony and later a kingdom of Dalriada there); or even as self-punishment for a misdeed in his youth—namely that he once copied a very beautiful Psalter and refused to gave it back, which resulted in a battle between monasteries.

On the eve of Pentecost the saint of God landed on the first piece of land where his native Ireland was no more in sight: it was the small isle of Iona in the Inner Hebrides (approximately three miles long and one mile wide), to the west off the coast of Mull, situated in the kingdom of Dalriada, which corresponds to today’s Argyll and Bute area. The name “Iona” may be of old Norse origin; its first form was simply “Ey” meaning “island”. It was (and still is) an exceptionally beautiful isle, though at that time it was deserted and windswept. A local ruler granted this island to Columba and he built a church and a monastery on it, making it his main base. Orthodoxy in the Celtic tradition was to be spread from this great center throughout Scotland, and afterwards to many parts of England and the continent through the labors of St. Columba and his numerous disciples and followers over several generations. This was the catalyst for the conversion of the Picts, Scots and northern British.

St. Columba became the first Abbot of Iona and ruled it till the end of his life. He spent the rest of his life in Scotland, only occasionally making journeys to Ireland for important matters. Living on Iona, the holy man prayed, read, copied manuscripts, taught and labored together with all his monks. Though he was the abbot, he carried out any hard work in the fields as any simple monk would, showing great humility. He would carry heavy sacks with grain from the fields, and bring flour from the mill to the kitchen. His ascetic life was so austere that it seemed to exceed human strength. The saint kept a strict fast, spent nights in prayer, slept on a bare rock and had a stone as his pillow (what is believed to be his stone pillow is kept on Iona to this day). Despite his extremely ascetic way of life, Father Columba was filled with the joy of the Holy Spirit and was always courteous and benevolent to everybody.

The supposed St. Columba's stone-pillow at Iona Museum (photo by J. Demetrescu from 'Saints and Stones' website)

The supposed St. Columba's stone-pillow at Iona Museum (photo by J. Demetrescu from 'Saints and Stones' website) Adomnan wrote that “He (Columba) had an angelic face, was of an excellent nature, perfect and polished in speech, holy in deed, great in counsel, loving to all.” Tall, thin and physically strong, Columba spoke with a strong and ringing voice. A great scholar and preacher, wonderworker and visionary, Columba was quite stern and hot-tempered in his youth, but with time he softened, becoming gentle and merciful. His humility and kindness extended not only to the monastery brethren, but to every stranger. A true faster and man of prayer, Fr. Columba always shared the joys and sorrows of all his neighbors. Adomnan and other biographers in one voice evidenced that this ascetic, “pure in body and chaste in his mind”, poured out abundant spiritual joy on everybody, being a chosen vessel of the Holy Spirit himself.

Taking compassion on a robber who intended to kill the seals that the monastery brethren ate, Columba began to give him food. All biographers portray him as a man of extraordinary wisdom and a good teacher of his monks. Well-versed in the Holy Scriptures, Fr. Columba knew Greek, studied chronology and astronomy (in particular with respect to the calculation of the Paschalia). He took special care for the proper celebration of Church services and the Eucharist. Once St. Brendan of Clonfert saw a ball of radiant fire above Columba’s head when the latter was serving the Liturgy. Adomnan called him “a pillar of many churches, the father of many monasteries.”

Perhaps Columba worked out and introduced a rule for Iona and other monasteries he had founded, though we know very few details of it. However, the surviving written evidence mentions the sources that Columba especially loved—the rules of St. Basil the Great and the writings of St. John Cassian. Apart from Iona, Columba was head of daughter monasteries and hermitages (sketes) on the western coast of Scotland (Hinba, Mag Lunge on Tiree—the most westerly of the Inner Hebrides—which supplied Iona with grain, Cella Diuni and others). He and/or his disciples also founded communities and cells on Jura, Skye, Ellen (not yet identified) and other isles and spent time on them for quiet prayer and contemplation. According to some information, Columba himself built a great many churches, and blessed 300 wells, baptized and cast out demons from hundreds of people.

At Columba’s monasteries the communal life of the majority of monks was combined with the eremitic life of some experienced ascetics. Adomnan points out the most important feature of cenobitic life on Iona:—life in true obedience to the spiritual mentor. Only adult men were tonsured monks on Iona, though very young disciples and novices were allowed to live at the monastery as well. The community was governed by the abbot who appointed the abbots of daughter monasteries.

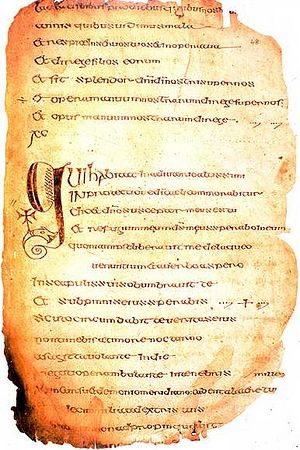

St. Columba was an excellent scribe and created many manuscripts. He compiled a Hymnal for the Week, and according to his biographers, he was the author of commentaries on the Bible, prayers, hymns, and poems, in addition to the rule mentioned above. But the most outstanding is, beyond all doubt, the “Cathach of Columba”—a splendid copy of the Gospel on vellum created by Columba himself before 561. This great relic, the earliest Irish manuscript of this kind, still exists and is kept at the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin.

Columba more than once visited monasteries in Dalriada and the Pictland. Iona monks crossed the sea in small wooden vessels and coracles—simple round rowing boats made of woven sticks covered with animal skins. When St. Cormac (a spiritual friend of Columba) with his companions, in the quest of “the desert in the ocean”, reached the north Orkneys, Columba saw in spirit that they were in imminent danger, so he asked a Pictish ruler to show them hospitality. This way the holy man “observed” in spirit all the travels and activities of his disciples, even in faraway lands. As soon as he “saw” any of them sinning or in trouble, he began to pray zealously for them. This spiritual vision enabled him to govern many monasteries “from a distance”. In all things life in Iona and other of Columba’s monasteries resembled a true family with a father and children.

The venerable man instructed monks and lay people alike, in some cases even prevented the breakup of families, and he never turned down any one coming to him and seeking his advice. He was concerned for the observance of Church discipline, censured clerics who boasted of their riches, was favorably disposed towards all who were zealous in doing penance, praised all who displayed compassion and hospitality to others. As can be seen in the Lives of great many Orthodox saints and elders both in the East and West, Columba’s Life contains many examples of his clairvoyance, how the faithful flocked to him, asking for his prayers, consolation and counsel in various life situations. The saint would often meet people standing on his knees, washed their feet, prayed for them with abundant tears (he had a rare gift of tears), prayed for sinners, like a loving father, and did not leave anyone unconsoled.

The Lives describe how a column or a cloud of unearthly light surrounded the holy father during his solitary prayer; how he conversed with angels and other holy men in spirit; how many secrets of the past and of the future were revealed to him by God (he predicted the day of his repose and many other events); how he explained difficult places of the Holy Scripture to people. St. Columba’s prayer was pleasing to God: those suffering were healed; miracles were performed even from the things and items blessed by him. The man of God maintained friendly relations with many other Church figures and ascetics of that time (Sts. Kenneth, Comgall, Brendan, Drostan, Kentigern); he instructed rulers, princes and members of royal families, in some cases preventing internal wars. Due to Columba’s influence the Church in Scotland became as strong as that of Ireland. By tradition bishops obeyed Abbot Columba, and after his death Scottish hierarchs continued to obey abbots of Iona.

His missionary work among the northern Picts was successful. Pictish pagan priests—the druids—despite all their attempts, could do Columba no harm. Many Picts had been so rooted in paganism that they initially met the Good News with hostility, but with time the situation changed—through the efforts of Iona monks and other Irish missionaries most Picts were baptized. Eventually the supreme ruler of the Picts, King Brude, was baptized by Columba in the ninth year of his reign.

Ionan monks travelled to the north and west, east and south, preaching the Gospel, sowing the seeds of Orthodoxy and the Irish monastic tradition. Thus they reached the Orkneys and Iceland, England and continental Western and central Europe. Iona became the spiritual capital of Scotland and the seedbed of missionary work thanks to Columba, whose influence in the establishment of Orthodoxy in the Celtic tradition in many parts of Europe cannot be overestimated. Ionan monks were fearless and modest soldiers of Christ, who “wandered” for Christ’s sake through the endless ocean, through mountains and valleys, bogs and forests, often living amidst hostile pagans; but wherever they came they brought the Good News and joy of Christ with them, and in many cases left humble cells, chapels, beautiful manuscripts and bells after them. On the sites of the cells of many of these saints rose the future great centers of monasticism, learning, and whole cities in present-day France, Belgium, Switzerland and other lands, most of which stand to this day. Such was the spirit of the Celtic monks, spiritual children of blessed Columba.

The man of God had to solve secular affairs as well. Some sources claim that he even stood up for the rights of women in Ireland. He prevented the expulsion of bards from Ireland and protected their traditional organization. Due to his role, many well-educated laypeople from all strata appeared in Irish Christian society. It was through the authority of Columba that in the Synod of 575, the Scottish king became independent from the Irish suzerain. The great authority of Columba and Iona contributed to the custom of crowning every new Scottish ruler on Iona.

Venerable Columba loved and cared not only for people, but also nature, seeing God’s creation in everything. Despite being busy with praying, copying or teaching, he often found time to look after the plants that the brethren grew for subsistence. It was said that during the building of Derry Monastery at the insistence of Columba the plan was altered so that they did not have to fell trees. Numerous stories testify to Columba’s affection not only for people, but also for mute animals. Once he saw a young crane that landed on Iona exhausted and could hardly move. He took pity on it and ordered one of his novices to take care of it and let it stay at the monastery until it gained strength. Another story tells that the monks were annoyed by the barking of seals on the shore during Sunday services. The saint one day came out of the church, approached the animals, instructed them and they instantly jumped into the water and never barked loudly on Sundays after that.

Here are some examples of Columba’s miracles taken from Adomnan’s Life. “Once, returning from the country of the Picts, at his prayers, contrary winds were changed into fair… In that same country he took a white stone from the river and blessed it for working of certain cures, and that stone, contrary to nature, floated like an apple when placed in water.”1 “In the same country he performed still a greater miracle, by raising to life the dead child of a humble believer.”2 “When he was still a young deacon in Ireland, the wine required for sacred mysteries failed, and he changed by his prayer pure water into true wine.”3 “He often saw, by the revelation of the Holy Spirit, the souls of just men carried by angels to the highest heavens. And reprobates he very frequently saw being carried to hell by demons.”4 Once local inhabitants complained about the profound bitterness of the fruit on a tree that grew south of Derry Monastery. The saint blessed the tree and it produced only sweet fruit henceforth. Another time he gave his monks three measures of barley and ordered them to take it to one poor man so that he could sow it. The disciples obeyed and, against the law of nature, the poor man sowed barley after the mid-summer and gathered it in ripe as soon as early in August.

During a pestilence in Ireland, Columba distributed blessed bread and ordered the infected people and cows to be sprinkled with the water he had blessed—and all were cured. A virgin living in Ireland broke her thigh. She lay and invoked the name of St. Columba. He heard her prayers from many miles away, ordered his novices to sail and give her holy water—and she was healed. He also predicted that that virgin would live for another twenty-three years. Once Columba blessed a lump of salt and gave it to a man called Colga, who passed it to his (Colga’s) sister who had been his nurse. Soon after that a fire began in her village but she was not affected as the salt was not consumed by fire. When one day Columba was travelling, a couple came up to him and asked him to baptize their baby. There was no water nearby. The saint prayed before a rock and a stream gushed forth from it: he baptized the baby and predicted that this boy would indulge himself in carnal pleasures in his youth but would become a genuine Christian soldier in mature age, would do many good works and die in a very advanced age.

In Pictland the saint blessed a “poisonous” fountain that locals worshipped as if it were a god, and whoever drank from it was infected—henceforth its water became wholesome. Once a young man who was carrying a pail with milk from the farm home asked Columba to bless him as he passed by his cell. The saint made the sign of the cross in the air—and the lid of the pail fell and broke, while most of the milk spilled out. The saint explained that the man out of negligence had forgotten to make the sign of the cross over the pail the before pouring milk into it, and the demon that was sitting inside it had now run away, unable to bear the cross. Then he asked the boy to come nearer, blessed him and his pail became full of milk again. The saint blessed a very poor but hospitable man, who out of kindness treated him with all he could offer, and predicted that his livestock would multiple a hundredfold; and he predicted to one very rich but stingy man who refused to give him shelter that he would lose all his riches and end his days in misery—and both prophecies were fulfilled.

Remarkably, it is the Life of Columba where the so-called Loch Ness monster was first mentioned: “When the blessed man was living for some days in the province of the Picts, he was obliged to cross the river Nesa; and when he reached the bank, he saw some inhabitants burying an unfortunate man, who had been a short time before seized, as he was swimming, and bitten the most severely by a monster that lived in the water. The blessed man, on hearing this, directed one of his companions to swim over and row across the coble that was moored at the farther bank. The latter obeyed without the least delay, taking off his clothes, except his tunic. But the monster, lying on the bottom of the stream, was only roused for more prey. As the man was swimming, it gave an awful roar and darted after him, with its mouth wide open. The blessed man raised his hand and formed the saving sign of the cross and commanded the ferocious monster: ‘Thou shalt go no further, nor touch the man; go back with all speed!’ The monster was terrified and fled, as if it had been pulled back with ropes.”5

When the saint’s faithful attendant Diormit was sick even unto death, Columba besought the Lord not to take his soul whilst he (Columba) was himself alive. And, indeed, Diormit recovered and even outlived the saint by many years. Columba liberated a Scottish slave girl from a druid named Droichan who held her captive. When the druid did not heed Columba’s warnings he was stricken by a severe illness; only then did he repent and let the girl go and was cured. When Columba with several assistants first arrived to the Pictish King Brude the latter behaved haughtily and refused to let them in. All of a sudden the gate to the royal palace opened on its own accord before the man of God. Once the king learned about it, he changed his ways and held the saint of God with great reverence until his death.

Once when Columba was visiting Ireland he came to the church of Tirdaglas. But for some reason it turned out that the church was locked. He approached the door with his companions and said, “The Lord is able without keys to open His house to His servants.” The bolts of the lock were driven back by some invisible force and the door opened by itself. On a certain day the saint arose from his reading in the cell and hastened to the chapel to pray hard on his knees. When he returned he explained to the brethren that at that very moment a little woman in Ireland had been suffering the pangs of a most difficult childbirth: she had invoked the names of Christ and holy Columba, hoping to receive help. So Columba sensed these prayers, was touched with pity for the poor woman, and through his intercession she happily delivered her child.

The holy man labored on Iona for thirty-four years. Feeling the imminent death of his beloved master, the monastery horse came up to him, put its muzzle on his chest and began to weep. Rising up on a hill, the saint of God blessed Iona and its monastery and predicted that this place would be held in reverence not only by the Irish but also by “barbarians” (then still unconverted nations), foreign peoples and saints from other Churches. He promised to intercede for his monks before the Almighty, provided they would keep peace and live according to the precepts of the Holy Fathers. Father Columba also predicted that after a period of prosperity there would be the abomination of desolation on Iona (“Iona of my heart, Iona of my love, here instead of voices of monks there will be mooing of cows”), but shortly before the end of the word Iona would again become a place of monastic life and there would be a (Orthodox) monastery on it. There is one more intriguing prophecy attributed to one of the Iona monks: Seven years before the Second Coming, a giant wave would cover much of Britain and Ireland, including the isles around, but Iona would remain above the sea right until the end of this world.

On the night when St. Columba reposed in Christ, a column of fire rising up to heavens was seen in the east of Ireland. Closer to the end of his life Columba was weaker, and spent most of his time copying books (allegedly he helped copy 300 manuscripts).

St. Columba, the Abbot of Iona, was venerated as a saint already in his lifetime. He was asked for intercession, his name was invoked by those in trouble, he was called “a refuge of the naked and feeder of the poor”. After the saint’s repose his veneration increased rapidly. Christian soldiers prayed to him before decisive battles with the heathen. This great saint appeared to the righteous king and the future martyr Oswald of Northumbria (+ 642) before his battle with the Welsh and the Mercians and predicted him an overwhelming victory over the enemy. On hearing this story many English people came to believe in Christ.

Bites of poisonous snakes that lived on Iona were harmless to people who kept the commandments. Thanks to Columba’s heavenly protection, Dalriada and Pictland were not affected by the terrible plague that was then devastating the whole of Europe. Supernatural light and angels were seen above Columba’s grave by many. Iona Monastery also preserved other relics associated with their patron: his white vestments, his personal staff and small bell (a common feature of Celtic saints), and books copied by his hand. When in danger, the brethren held a strict fast, laid the holy objects on the altar and invoked the saint’s name. Amazingly, neither water nor fire could do any harm to the books he had copied. As is seen in the Lives of some Irish saints, even the manuscripts associated with Columba and hymns composed by him appeared to have had miraculous properties! In cases of drought believers took the white tunic and manuscripts of Columba in processions, placed them on the hill where a multitude of angels once appeared to Columba, prayed—and God sent them bountiful rains for the saint’s virtues. People in Ireland and Scotland built cathedrals and monasteries that they dedicated to this blessed man of God.

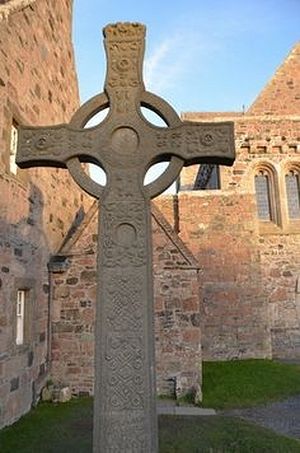

After Columba, Iona produced a host of other saints, including holy abbots. Iona was the nucleus for practicing and spreading Irish ascetic practices, Irish monasticism, learning, culture and education and influenced spiritual life of many people for generations to come. Many monasteries on the Irish pattern were to be built in Scotland, England and mainland Europe. Iona had wonderful scriptoria and the monks of Iona created such masterpieces as “The Chronicle of Iona”. In the eighth century, no fewer than 360 so-called “high Celtic crosses” were erected on Iona.

From the beginning of the ninth century, Iona was subjected to repeated attacks of the pagan Vikings; during one of these raids, in 823, the Danes murdered the holy abbot Blathmac with all his monks right on the steps of the altar of Iona church (he is commemorated on January 15/28). Thus the holy relics of Columba with the rest of the monastery’s shrines were translated to another part of Scotland—to Dunkeld (now in the Perth and Kinross area) where it was safer, and later to various locations in Ireland, notably to Kells, which still has a holy well and a very ancient “house oratory” of St. Columba. In the Middle Ages, according to one version, his relics were enshrined at Downpatrick Cathedral in what is now County Down in Northern Ireland. It was claimed that this Cathedral also housed relics of Sts. Patrick and Brigid. However, in the sixteenth century all the relics of the cathedral were destroyed by the Protestants and it is impossible to ascertain if this tradition is authentic.

The name of Columba is present in many early Scottish and Irish calendars. Adomnan provides the first evidence of the liturgical commemoration of the saint on Iona. The famous Martyrology of Tallacht (eighth or ninth century) indicates the feast-day of Columba under June 9; in the Martyrology of St. Oengus St. Columba is mentioned in a quatrain, and in the list of ranks of saints there he is called “the head of the saints of Britain”. In the Middle Ages his veneration spread all over Scotland and Ireland, and later, through the Hebrides, it reached Iceland, where one of the first documented churches was dedicated to him.

A Benedictine Catholic monastery in honor of St. Columba was founded in Iona in 1203, and an Augustinian nunnery appeared in about 1208; it existed until the dissolution of monasteries during the Scottish Reformation. By that time Scotland alone had forty-five churches dedicated to its holy enlightener. The veneration of Columba on the Hebrides, which are very isolated in comparison with the rest of Britain, continued at least till the end of the seventeenth century.

The veneration of Columba on the continent is mainly due to Irish missionaries who travelled to Frankland to preach Christ. The liturgical commemoration of Columba can be found as early as in the calendar of St. Willibrord compiled before 717. Later we see his name appearing in the calendars and litanies of the lands of Franks. He was deeply venerated in many of the major European monasteries, for example, at St. Gallen in what is now Switzerland. Today dozens and dozens of Catholic, Anglican, Episcopalian, Presbyterian and other Protestant parish churches are dedicated to St. Columba in the UK, Ireland, North America, Australia, Italy, Germany and other countries. There are holy wells in Scotland and Ireland which bear his name.

From the twentieth century the revival of the veneration of this saint among Orthodox Christians, including Russian-speaking believers, began as well. There are Orthodox icons of Columba, a complete Orthodox service to him in English and even an Akathist in French! There are at least two Orthodox parishes and one Orthodox monastery (Romanian, located in Southbridge, Massachusetts) of St. Columba in the USA; Orthodox communities in honor of this saint can be found in the UK and Ireland as well, they belong to the Patriarchates of Constantinople and Antioch.

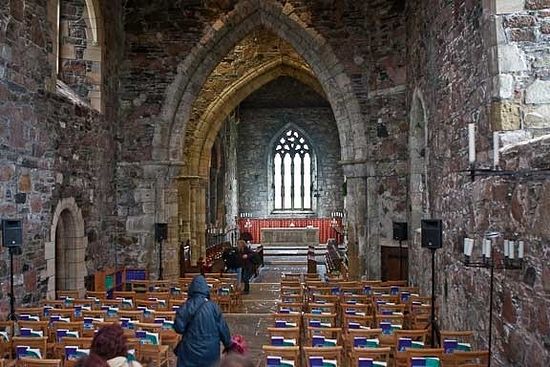

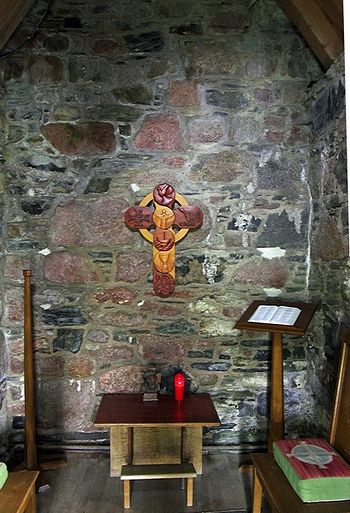

Pilgrimages of Orthodox Christians of different jurisdictions are regularly organized to Iona: the place of spiritual labors of Columba. The faithful visit the St. Columba’s large former abbey church which was substantially rebuilt in the twentieth century along with other buildings of the monastery complex; the ruins of the medieval nunnery; the heritage center of Iona displaying many relics; and other treasures and ruins, scattered across the isle, especially ancient crosses. The main shrine of the reconstructed abbey church is the twelfth-century restored shrine chapel of St. Columba where his grave presumably was situated. The chapel is at the front of the abbey church and its origins are of the ninth century. In the north transept of the abbey church one can find a very ancient effigy of Columba in a niche, which is the oldest surviving carving within the temple.

Among interesting parts of the church is a side-chapel to the right of the altar designed for quiet private prayer and meditation. There are many icons and candles inside it, a feature which is so close to the hearts of Orthodox Christians and in the same spirit as Columba. The present magnificent church owes its existence to a Presbyterian clergyman from Glasgow, Revd. George MacLeod, who arranged the roofing and partial rebuilding of this holy site in the 1930s and established the “Iona Community”. This community is not monastic, but its Protestant members strive to preserve and promote the Irish Christian heritage of the past, organizing pilgrimages, recording and producing spiritual hymns, prayers and other works.

Among other notable objects on the isle are the Abbot’s Hill with some minor ruins where, according to tradition, Columba had a solitary working cell and used to pray and write; a twelfth-century chapel in the area of a cemetery where numerous Scottish, Irish and Norwegian kings were buried; and a hill where, according to tradition, Columba communicated with angelic spirits. The supposed pillow-stone of the saint is kept in the abbey museum. Among crosses on Iona the following two are particularly worth mentioning: a complete ninth-century and impressive St. Martin’s cross (with several original details on it, such as the Mother of God with the Christ Child and scenes from the Old Testament) and the exquisite replica of a very large St. John’s eighth-century cross, which looks very Irish.

For thousands of believers from across the globe Iona is by far the most beautiful, charming, living and holy isle in the world. All sense the transparent yet invisible presence of St. Columba on it. People who have visited it admit that the beauty of its landscapes and the whiteness of its cliffs are special, the purity of its air is special, the blueness of the sea around is special, the brightness of the sun above it is special, and the tranquil atmosphere there is special. Iona has fascinated many artists, poets, travelers, scientists, romantics, ordinary folk and royalty from various countries throughout the centuries. Among those who were enchanted by it are the writers James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, the poet William Wordsworth (who devoted four sonnets to it), John Keats, Felix Mendelssohn (visited at the age of twenty), Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Queen Victoria (she visited at least in 1847), the French novelist Jules Verne, the Scottish painters Samuel John Peploe and Francis Cadell, the Scottish architect Robert Adam, the landscape painter William Turner, Alice Liddell (the prototype for “Alice in the Wonderland”), and the Scottish-born explorer David Livingstone, to name just a few…

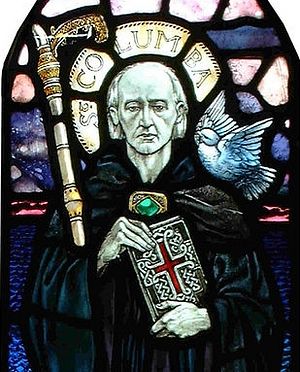

There are many stained glass windows and statues of St. Columba in Catholic and Anglican churches. He is usually depicted in stained glass in monastic robes, holding a book and a pastoral staff. In the Roman Catholic tradition he is venerated as the patron of book-binders, poets, as a protector against floods. Many Catholic schools and colleges are named after him. Many towns, villages, districts and other place-names across Ireland and Scotland bear the name of Columba—for example, Glencolmcille in Donegal.

Thus Columba, one of the most beloved saints of Ireland and Scotland, perhaps the greatest Church figure in the early history of Britain, is not forgotten and is loved 1400 years after his death.

***

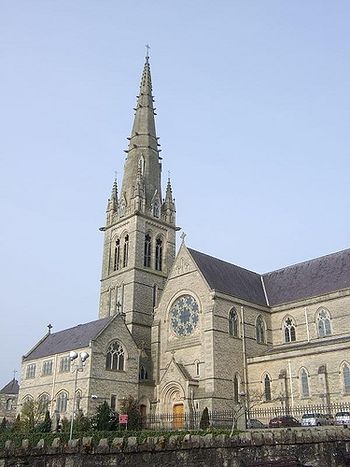

Let us mention some of the huge number of the churches that bear the name of Columba. In Ireland: the seventeenth-century Anglican cathedral in Derry which stands on the site where the saint built a monastery; the Catholic Cathedral of Sts. Eonan (Adomnan) and Columba in the town of Letterkenny in Donegal (built by 1900; its stained glass depict scenes from Lives of Sts. Columba, Adomnan and other saints; it has twelve bells each of which is named after a saint of Ireland, including Sts. Adomnan and Columba); the eighteenth-century Catholic church in Long Tower in the heart of Derry; the Anglican church (Church of Ireland) in the town of Omagh in Tyrone; the church in the saint’s birthplace at Gartan—this town also has St. Colmcille’s Heritage Center devoted to the life and works of Columba and telling visitors how Celtic monks illuminated manuscripts and many other things; a large church with an early round tower in Swords where he founded a monastery.

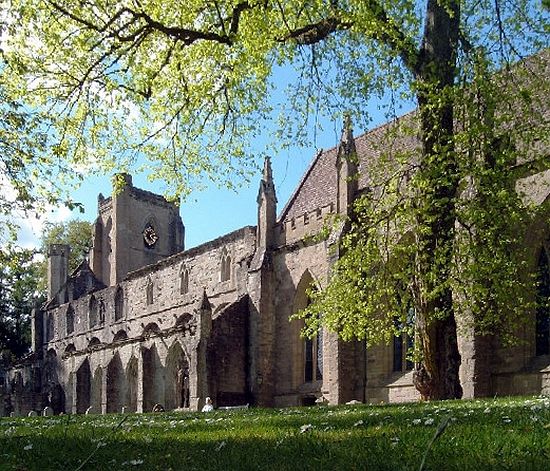

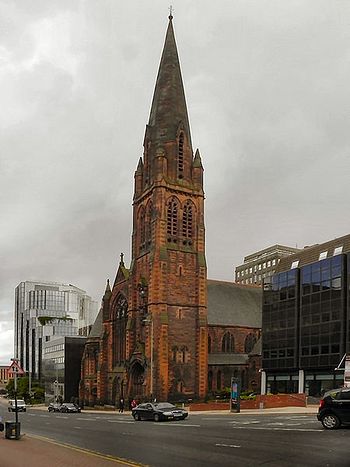

In Scotland: a Church of Scotland church in St. Vincent Street in the city of Glasgow (dates to 1770, services are held in Gaelic and English); a chapel near the village of Bunavullin in the Highlands council area; the Roman Catholic twentieth-century Cathedral of St. Columba in Oban in the west of Scotland opposite the isle of Mull. The town of Dunkeld still preserves the ancient former Cathedral of St. Columba which was built around the thirteenth century. It stands on the bank of the River Tay. Its architecture combines the Gothic and Norman styles. Although some of its parts are in ruins, the Cathedral is still used as a parish church by the Church of Scotland (which has no bishops and, therefore, no formal cathedrals). The first monastery or Cathedral appeared here in the sixth or seventh century by Columba or his successors. The monastery managed to survive in spite of Viking raids, especially in 903. A large portion of Columba’s relics were kept in this Cathedral from the ninth century probably until the Reformation, when they disappeared; although some archeologists believe that they may lay buried near the Cathedral. The Cathedral has a small museum displaying finds and relics from its former monastic and Irish past.

Dunkeld Cathedral, Perth and Kinross

Dunkeld Cathedral, Perth and Kinross

Another site closely associated with our saint is the isle of Inchcolm in the Firth of Forth off the eastern coast of Scotland. According to tradition, Columba visited this isle. Later it was a center of the Culdee movement and a dwelling of hermits. In the twelfth century on the orders of a king of Scotland an Augustinian Abbey of St. Columba was founded here. In the late Middle Ages Inchcolm Abbey became so popular that it was nicknamed “Iona of the East”. This isle is still a magnet for pilgrims: the partly ruined buildings of the Augustinian monastery have been perfectly preserved and include a church, a tower, a cloister, and a chapter house, making Inchcolm a place with a former medieval monastery in the best condition. Apart from the abbey, this isle has partly survived ninth-century hermits’ cells. The name “Inchcolm” means “Island of St. Columba” in Gaelic. Another isle has exactly the same meaning. This is called Eilean Chaluim Chille, situated in the Outer Hebrides off the east coast of Lewis. It has the remains of a very old church in honor of St. Columba, which was built in about 800 and was formerly a great pilgrimage destination.

Even London can boast a Church dedicated to St. Columba. It stands in Pont Street and is one of two Presbyterian parish churches in the British capital.

Holy Father Columba of Iona, pray to God for us!

God bless you.

Christos.