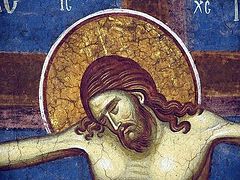

This weekend marks the mid-point of the 40 days of Lent. And on this middle Sunday of that journey, Orthodox Christians around the world focus on the Holy Cross.

Literally.

At tonight's service, a special cross decorated with flowers will be brought from the altar of each church and placed in the middle of the sanctuary. Over the coming week, the faithful will bow before it as we enter and leave, making three prostrations and kissing it with reverence.

To any outside observer, especially one coming from a more intellectualized and less incarnational form of modern Christianity, this physical ritual probably seems odd and uncomfortable. Bowing. Kneeling. Kissing things. It all sounds so primitive.

Contemporary Christianity has become rather abstract and immaterial (even anti-material) in its worship. Beautiful decor (even beauty itself) is suspect as a potential seduction of the devil. So, plain white walls. No altar (no need, because no Eucharist). Maybe a cross, as long as it's not too pretty or distracting. Such are the aesthetics of now.

By contrast, the physical and sensory worship of an earlier age seems foreign. But I was reminded how normal it once was when I recently came across a passage from the second-century writer Tertullian about another physical gesture of prayer many Christians no longer know: the sign of the cross.

In a document called "De Corona" ("On Crowns"), this North African Christian addresses a novel assertion made by some Christians that only practices explicitly mandated by Scripture need be followed.

He counters that many ancient practices are passed down by tradition, without scriptural mention. One is described thusly: "At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign (of the Cross)."

That Tertullian takes for granted the universality of this sign (to which no opponent could object) shows how common it was to his age. I'll add this to my apology against those who object that this sign is unbiblical, because not mandated by Scripture.

After all, many things are biblical, without being in the Bible. For example, the Bible nowhere says Christians should wear crosses around their necks (another ancient tradition). Yet, many who criticize the sign of the cross wear crosses.

So, prostrations, signing the cross -- or any act of prayer that incorporates soul and body together -- may seem foreign, but are no more unbiblical than all those Bible passages about people falling down in reverence before the very presence of God.

And that's what ultimately makes prostrations before the cross so meaningful: the opportunity to offer an unreserved act of worship, with our entire being, to the one who died on it to save us.