A summer evening; a storm cloud is hovering over the village of Klykovo, spreading out over the hilly bank of the swiftly-flowing river. On the way up the hill, straight into the storm, a monk quickly ascends; he’s quite young and athletic, with earphones in his ears. People continually drive by, stop and offer a ride, but the monk just shakes his head. “I need to walk a lot! May the Lord save you!” “May it be so!” the people in the cars say, clearly touched, and drive on further. This monk is an embodiment of the entire monastery of the Hermitage of the Savior Not-Made-By-Hands. The monastery is also young (sixteen years), tempered by trials, and everyone is amazed—by its history, or, for example, by the interior of the new church—it has a glass roof, so it’s always filled with light. Or take miracles—we all love them: They happen here nearly every day, mostly through prayers at the grave of Mother Sepphora—a locally-venerated saint, known as the Heavenly Bird by the people. Igumen Michael (Semenov), deputy abbot of Klykovo Monastery, speaks on Matushka’s role in the appearance of the monastery, on the difficulties and victories of the brethren, on the continuity of love, and much else in this candid conversation.

“We were just surviving”

—Batiushka, you are one of the founders of this monastery. It all started in the early 1990s; you were young then, and, as far as I know, you were working in the nearby Optina Monastery, and you suddenly left there with your brethren and went to Klykovo. What drove you? Why did you exchange a famous monastery for a decaying village with a dilapidated church?

—I arrived at Optina in 1992. It was a very good time, when the Orthodox reached out for one another. There were one, two, three, four of them in any given city, and they all knew one another, they all burned with the desire for spiritual labors, the idea of restoring churches, monasteries… It was a time of unity for sincere Christians. It was a good time of unity and sincerity in Optina too, but there were negatives along with the positives. Having gone there as workers, despite everything, we did not have enough spiritual guidance. We worked hard, everyone was laboring selflessly to revive Optina, but, despite this plowing, it lacked some priestly warmth, brotherly warmth. I don’t know why they didn’t have it then; I can’t answer that. They just didn’t.

But not far from the monastery, in the village of Novokazachii, there was a Hieromonk Peter (Baraban). He was already 70; he had experienced a lot, spent eleven years in a prison camp… Batiushka was available; you could always go see him. And we, ten or twelve people, would leave Optina to go see Fr. Peter on foot, over the river, across the bridges… We would go and have spiritual conversation with him, and we were comforted.

Some time passed, and they offered Fr. Peter the church in Klykovo. There was a man living there, Vladimir, a lawyer; he was a believer and a spiritual child of Fr. Kirill (Pavlov), and he had undertaken the restoration of this church. But restoration is restoration—they needed a priest—but where to find one in those years? He started asking Fr. Peter: “Batiushka, come serve here.” Somehow it all came together that they offered Fr. Peter to be the rector here.

The next time we went to see him, he was glowing, “They’re giving me a church, brothers! Come—we’re going to make a skete.” We all as one said that we couldn’t leave the monastery of ourselves, but if we get a blessing, then with pleasure! I, at least to some degree, was ready to leave. I soon left for another Optina work trip in Minsk, and when I returned, I found out that Fr. Iliy (Nozdrin) had already blessed a number of workers to go to Klykovo. I also went and asked him what would happen with me. He said to me, “Yes, yes, go and help.” I exhaled when he said that to me, because I understood that it was not my own petty will, but there was some meaning in it. And so it happened that we packed our things to leave within two days.

—It’s interesting that when they were closing the Optina churches one after another in the 1920s, a part of the brotherhood went precisely to Klykovo. However, in the end, the Church of the Icon Not-Made-By-Hands was also ruined. Which church was it that appeared before you?

—A desert! Except for grass taller than your head, there was nothing here. There was nothing at all! Neither a roof, nor windows, nor doors… They were storing fertilizer in the church. We arrived to a bare place. It was only by the efforts of the lawyer Vladimir, about whom I spoke, that some work was done. Thanks to him, over the course of two months we managed to put the left altar, to the Holy Protection, in order, install doors, glaze the windows, and to make a plywood iconostasis and altar. We arrived in August, and we were celebrating Liturgy already by the end of October, although there wasn’t even any plaster there, and the bricks were falling on our heads. The most interesting thing is that they fell when we weren’t in the church. Not even one brick fell during the services. It’s just amazing, you know! The dome was all flawed, split, bricks were hanging, and they really could have fallen on us. But we just prayed, and no one thought about any danger; everyone understood—the Lord protects us—and that’s that.

—That’s faith!

—There were times when we were picking mushrooms, we ate them, and then we realized they were poisonous; but nothing happened—no one died! Then the locals told us that, apparently, they’re inedible. But we’re fine. (Laughs.)

We arrived in 1993. At first there were eight of us, then twelve (and today twenty!), and for the first two years we were just surviving.

—I read in one of your interviews that sometimes you didn’t even know if you would have food the next day…

—We divided our bread into pieces. The sugar would run out, and some babushka would bring us a bag of sugar. We didn’t have enough money. We never had any during those years in general. We lived on the donations that people would bring us.

—By the way, how did the locals relate to you then? People were keeping to themselves, not particular missing anything, and suddenly some priests start flocking in, restoring the church, building some other things…

—They received us poorly! You can compare this place with Kronstadt. When Fr. John of Kronstadt arrived there, there were exiled soldiers, and we have the 101st kilometer[1] here… Nearly every local here is a former prisoner. I was naïve in my youth, thinking I would be able to preach to them all, that they would all repent and become parishioners of our church! Only a young priest could have such an idea—old priests don’t have this opinion anymore, because they have experience and a real understanding of what is happening; that is, that noble roses do not grow out of weeds—we must understand, clarify, and remember not to waste time.

The locals were far from understanding Orthodoxy, much less monasticism. They thought that if we don’t hang around with girls, then we must just be physically sick boys—they thought we were planning to make a shelter for sick children. We didn’t run around with the local girls, even though the oldest of us at that time was only twenty-five years old… The locals had no concept of a monastery. For all my efforts, five or eight babushkas would come to the services. I would try to talk with them, give them some literature, but it all ended in panhandling—to borrow money and not repay. Nobody repaid, even once. What kind of fellowship can you build with people who have no conscience? If someone doesn’t have a conscience, then what spiritual principles can you use to build a relationship with them?

“The principle of love is disappearing from society”

—Did the Klykovo locals change their attitude towards you and the parish later on?

—Experience has shown that they have not. Our parishioners are visitors. The locals are dying in terrible conditions of alcoholism or from something else—each one has died terribly. I used to go to the village kindergarten, to talk with the children, to try to at least change something, and they, like all children, lit up at my stories. But imagine: I’m leaving, and the teachers start telling them that man evolved from apes. What picture will the children have in their heads in the end?! How can they combine our origin from God with an origin from apes? Who should they believe? They go home, and their parents say the priests lied! I’m telling you how it is.

Our people were forced into such a slavish condition, that, to speak honestly, they haven’t come out of it yet! Because for someone to teach something spiritual, first you have to teach something moral. You need a moral foundation upon which to build the spiritual. But if there is no moral foundation—a foundation that parents alone can place, and not the priest—then the Church cannot reeducate. Priests were not engaged in education before the revolution. This was the job of the family. The priest was like a judge, identifying: whether they transgressed or didn’t transgress their responsibility. They admonished. If a person had a conscience, then he would receive the admonishments of the priest and try to correct himself. The priest only regulated. What do people want from us now? That we be nannies—and not only for the younger generations, but for the older, already degenerated generations, that we would babysit them and try to dissuade them from something about which they’re already convinced. It’s absurd!

—And everything should be some kind of recipe for salvation—if not of the rooted generation, then of those which follow after…

—We have to create incentives for moral families.

—How can we create this incentive?

—By creating the conditions for a family. It was a good principle before the revolution, when the village community, consisting of several families, basically relatives, formed a common spiritual climate. There were general rules, the same for all, and children, living in such a community, saw one moral layer and one moral principle. They didn’t hear, but saw how to be! Much is said now about how we should be, but examples for emulation becoming fewer and fewer. You can teach your child correctly, but he’s going to look at his neighbor or irresponsible teacher who shouts at the children because he has no love… The principle of love is disappearing from our society. And if nothing is built on this principle, then, as the apostle Paul said in the First Epistle to the Corinthians, in the thirteenth chapter, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. If you have no love, it means you are nobody.

The principle of love is the principle of continuity. Love does not arise only in the moral teachings of a priest, giving a homily. Love is born only in a family; and no monastery, and no shelter can teach it. And thinking they can teach it, we deceive ourselves—it’s self-delusion.

“It was the providence of God that a monastery would be founded on this spot”

—Let’s return to the monastery theme. So, the brothers in Klykovo found themselves strangers amongst their own people. Poverty, trials… it’s difficult to withstand all that. Did any brothers leave? What gave strength to those who stayed?

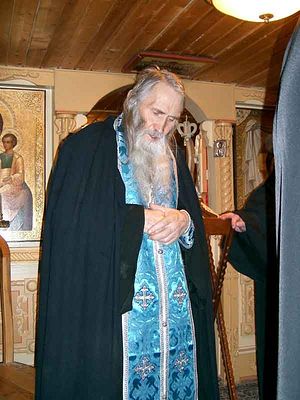

—Of course there were changes: Some left, some couldn’t endure. It all happened. The euphoria lasted the first half-year, but the enemy did his job, of course. But it was the providence of God that a monastery would be founded on this spot, because in 1993, when we arrived at Klykovo, Matushka Sepphora was praying in the city of Kireyevsk that the Mother of God would bless her to go to a monastery. Matushka knew when she would die, and she wanted to live and die in a monastery. The Mother of God appeared to her and said, “Do not worry, you will not die in the world. Wait, priests from Klykovo will come for you.” She waited for us until 1995, because if we had gone to get her for some reason in 1993, we would have had no place for her; we ourselves just lived in various buildings around the church, which did not belong to us. The building that is known today as the home of Matushka Sepphora is the first housing building that we built.

—It turns out that God’s providence was about you, for the priest that went for Matushka was you. However, when the Theotokos appeared to her, you weren’t ordained yet…

—That’s how it happened. Fr. Peter was old and sick, and it was hard for him to come here, and there wasn’t even a road from Kozelsk. Do you know how we drove him?! Someone donated a Moskvichok[2] to us that didn’t run, so we hitched the car behind a tractor, sat Fr. Peter in the Moskvichok, and pulled him here from Kozelsk with a tractor. That’s normal, right?! And in the winter! You could freeze in the Moskvichok on the way here—it’s about an hour’s drive. Batiushka stayed with us for a year and a half, and applied to Vladyka in Kozelsk. We were without a priest for a while. They ordained me first as a deacon, and then in 1995 as a priest. They ordained me right after I met Matushka Sepphora!

—Matushka’s arrival was a turning point for Klykovo, as I understand it. Things really took off from that point on?

—We went to see her to ask her to pray for us and to receive her blessing, and we believed that we would settle the skete. We didn’t even have the thought that we would disperse and that the parish would remain here. The Klykovo church had the status of an archbishop’s podvoriye (residence), where a monastic community was officially registered, which we arranged in the first years.

—The church was rebuilt in these years, a fence was built, housing. In all, the monastery was built in eight years. You finally achieved the status of a monastery in 2001—the first in new Russia. The fact that you built it is already a miracle in and of itself, but something even more miraculous happened later. The monastery suddenly began to attract people, and not just pilgrims, but people who have stayed in Klykovo forever. They built houses and moved their families here. Something similar happened when St. Sergius of Radonezh founded the Holy Trinity Monastery. Who are these people today, choosing life by the walls of a monastery? What share of all Klykovo residents are they?

—Eighty percent of Klykovo residents are Muscovites, and the process of their migration still continues today.

“Whoever came, fell ‘ill’”

—The peak of construction was 2005-2006. That’s when the outflow from Moscow happened—those who had earned something, were getting older, began to build second and third houses for themselves—that was the process.

—But what drew them to Klykovo?

—I think it was believers moving nearer to a monastery, to a church; and Matushka Sepphora was becoming more and more well-known. There was a period of time when she was not so glorified, as in the 2000’s, because it was all passed around by word of mouth; we haven’t done anything to advertise to glorify Matushka. People who received help at her grave already considered this place close and told people about it… Others would come, and they also got “stuck” to this place. It became quite dear for people.

I will say: Whoever came, fell “ill.” People can accidently wind up here, for various reasons, then they can’t explain why they come here, and even stay—the soul! They just want to be here. People come, and their first impression, which they cannot explain is: It’s good here! And good means blessed.

When I came here for the first time, I had the same feeling. It happened even before we left Optina. There were monastery fields not far from here, and the fathers asked me to prepare them for haymaking. I went to do something on a tractor. I drove passed Klykovo, saw a church, stopped by, sat on the bank and was dumbfounded. I was just “floored;” I sat and thought: I could dig a hut here—and what else do I need from life?! I had such a feeling—what else do I need from life?! I felt it, I understand it, and I’m still in such a state, and wouldn’t want to exchange Klykovo for anything. The soul is somehow unveiled differently here. It is a place marked by God. How can I explain it? Is it written somewhere? Do we have some wonderworking stone? No!

—It’s not necessary to explain to believers, but everyone else’s reason demands some logical version. How can we understand Muscovites who toss everything and drive into the wilderness, to a monastery, and not just the elderly but the young too?

—People don’t decide immediately: They come, and come, and then they think: Where do I spend more time? In Moscow or here? They realize: It’s better to live here, and to go to Moscow to take care of some things. I went to Moscow in 1993, as I still do sometimes. When I told the Muscovites that I spend several hours on the road from Moscow, they were perplexed: “What? It’s the taiga—Aleutians and bears live there—why do you live there?”

I always say that when I received a blessing from Matushka Sepphora, I went to the capital to look for donations with photos of our ruined church. I went to a famous firm, showed the photographs, and the director looked at me and asked, “Why?” I said, “Well, I’m building a monastery,” and he sincerely did not understand. “Why? Half of Moscow is filled with ruined churches—take any one and restore it.” “Here,” he said, “I would understand. People live here, but why there?”

The whole country was aspiring to get to Moscow then, but we felt something pulling us away from Moscow at that time. Of course, what kind of relocating here in 1995 could we be talking about? Who wants to live in the “taiga?” Everyone came here later, in the 2000s. When people were sick and tired of traffic, of constant anxiety… After all, a man can’t be in a constant state of nervous depression just to have a two to three room apartment in the city. The value of it is eventually gone. First there is joy that you have an apartment in Moscow, then you get sick of it and you think, “Why do I need this? It’s better to go listen to birds, to run after rabbits in the forest.” Glory to God that people’s values have somewhat changed. No one in Klykovo, or in many other villages, is surprised by Muscovites anymore.

—You have quite a number of pilgrims too. Do they all come to Matushka?

—They come for various reasons. We have wonderworking icons that people come to pray before, for example the icon “Helper in Childbirth.” A huge number of women who either cannot conceive, or cannot carry to term, knowing that we have this wonderworking icon, come to pray. It’s unusual, I’ve never seen this type of icon before, and miracles truly do happen before it. Write about it so people will know!

“People perceive the monastery as an almshouse for adult men”

—Among the brothers, do you have any that came here as usual people, but decided to stay in the monastery?

—Of course! Various brothers, and some were even businessmen… We had a Fr. Peter, a very colorful man; he’s from the “Afghans” [veterans of the war in Afganistan] and he had a typical business for an “Afghan:” He worked with nonferrous metals, exporting them abroad. But when he providentially came here, he chucked it all and became a cellarer. This happened during Matushka Sepphora’s time, when we were still beggars. He didn’t come to an inhabitable place, but to the very dregs of life. But the Lord took him: He got into a car accident and died a few days later. He was extraordinary, and very interesting. As active as he was in business, he was just as active in the monastery.

Today there are fewer like Fr. Peter. People more often perceive the monastery as an almshouse for adult men. It’s a bad trend. First, some ask: “Does the patriarchate finance you?” I have to hear this constantly! I just can’t figure it out: The patriarchate should take on financing us?! (Laughs.) That they think we came here, we get support, they give us money, and we live on this money. But that people should themselves get involved in the life of the Church—they don’t understand.

—Do people come to the monastery today for “freebies”?

—There was a period twenty years ago when everyone worked hard, and this is the result of the work—everything is beautiful, everywhere gold and expensive icons. Now we have a different problem: Now we have to support everything, and that more expensive than building. Those for whom this was done should support it—do you understand the point? But those for whom this was done want to get more out of it—absurd!

—Looking at your monastery, the uninitiated of course, think: Everything is so beautiful—that means there are rich sponsors, or the state gave money. Few think about the great work that was done here, to accomplish the miracle of the monastery’s appearance.

—Not a ruble from the [state] budget was spent here; no one took any money from the state! Everything was done with private donations; people parted with their money, and not with money they got from a bribe and then pass around, but people really helped, because they sincerely parted with their money. And it is dear, because there was no greed, no kind of reticence. Honestly, we all know what the modern history of our state is founded upon, but we did not take part in this. Therefore we perhaps have not defiled this place falsely: We didn’t try to pull the wool over anyone’s eyes with money stolen from the country, as if we were some unusually rich monastery. We’re not looking for riches; we just did everything well and beautifully, and people, having played a part, truly gave something from their heart and soul and now come here as to their home. We don’t have any other kind of people.

—You’re able to cope with your needs today?

—We manage. Is there any other option? We got ourselves into this situation.

“Whoever knew Matushka in her lifetime is not surprised by miracles”

—One last question, Fr. Michael, which our readers will not forgive us if we don’t ask. Please tell us about the latest miracles worked through the prayers of Matushka Sepphora.

—You should ask the local women about that. We monks have the attitude of, “Okay, miracle after miracle…” but for them—it’s a whole event! (Laughs.) We have recorded everything, we keep a book, but really—nothing surprises us. I recall something not long ago, of which everyone took notice. A group of pilgrims came—nothing out of the ordinary. I was busy with something and watched from the window as a man on crutches slowly walked to Matushka Sepphora’s grave. He went alone (the group was off to the side), and leaned on his crutches. He did not sit, but stood, prayed, and just as slowly walked back to the bus. A short while later, I was walking through the monastery, going about my work, and I noticed another picture: A man running, his pant leg rolled up to his groin, and yelling, “Look, look!”

I didn’t yet realize that it was the same man with the crutches, because I couldn’t understand why this crazy guy was running around with a bare leg. I went up to him and said, “Look at what?” The skin on his leg was hanging in folds. It turns out he had gangrene, blood poisoning, and his leg should have been amputated, but he’s a believer—he fled the hospital, got on the first pilgrimage bus and came to us. He came to Matushka Sepphora’s grave, asked for help, left for the bus on his crutches, and fell asleep for ten minutes, no more. He woke up and realized that his leg was healed. It was swollen, and within ten or fifteen minutes it had healed. Naturally, he began to run—not walk, but run!

All kinds of stuff happens. One woman from Bryansk was leading an excursion; her mother-in-law was a Muslim and she had bone cancer, at a serious stage as I understood it. The daughter-in-law took some oil from Matushka Sepphora’s cell once, went home, told everyone about the Klykovo miracles, and anointed the diseased spot on her mother-in-law with the oil. She was completely healed. The whole family got baptized then. It also was an extraordinary event. It wasn’t just a tooth that stopped hurting—such a serious stage of cancer, a woman on the threshold between life and death, of course, is remembered more than anything else.

People are constantly writing to us about miracles that happened to them, but whoever knew Matushka in her lifetime is not surprised by miracles. I would go see her in the mornings, and she would tell me: “I was in this monastery, and I was in this monastery, and I venerated this icon…” Can you imagine? If you didn’t know Matushka Sepphora, you would think, “What monastery was she in?!” She sits in her cell, blind, never budging! That is, either she’s crazy, or highly spiritual. Do we know of many saints that could allow themselves to move through space and be wherever they wanted to be? Matushka was of an unusually high spiritual life, an angelic life. The Lord bestowed upon her every sort of spiritual gift. So, if she was this way in her lifetime, then what should surprise us now after her death?