The Vaga St. John the Theologian Monastery was founded in 1426 by the Novgorod mayor, Basil Stepanovich Svoezemtsev. It is located at the confluence of the Pinezhka and Vaga Rivers, in what was then the Novgorod region. In 1764 the monastery was closed as result of Empress Catherine the Great’s secularization of religious structures. Today on the territory of the monastery is a chapel, which is the only building of the formerly huge monastery that has been preserved. On June 8, 2007 a miracle-working icon of St. Varlaam of Vaga, which dates to the eighteenth century but was lost after the revolution in 1917, was found in the chapel. This sparked a movement to restore the St. John the Theologian Monastery.

Now the village is called Smotrakovskaya, and the location is part of Archangelsk province. Another name formerly ascribed to the monastery was the Three Holy Hierarch Hermitage.

There is also a holy spring in the village of Medleshi, nine kilometers from the Theologian Monastery, which according to tradition is where St. Varlaam spent time in solitary prayer and asceticism. The spring appeared there at his prayers, and is called, “Varlaam’s little well”.

Varlaam's well in the village of Medleshi. Photo: blagozdravnica.ru

Varlaam's well in the village of Medleshi. Photo: blagozdravnica.ru

Many years after the death of St. Varlaam of Vaga, when all who could personally testify to his monastic podvig had died, the monks of the monastery he had founded, as a hagiographer relates, began to consider him as “not one of the saints, but an ordinary man”... This disposition was pervasive in the monastery and was not just the misperception of a skeptical monk. “Many doubted in him.” This notion is almost unique in ancient Russian hagiography of monastic saints!

What lies at the root of the monk’s skepticism in the monastery organized by Varlaam? What made the brothers relegate the saint to the unknown masses of monks?

The thing is that over the time that had passed since the St. John Monastery had been established, as well the town near which the monastery was located, St. Varlaam was always thought of as the man who had founded the town, the churches and monasteries both inside and outside its borders.

Being a prominent politician and a gifted manager of his era, and fairly keen on where the wind of history was blowing, Basil-Varlaam managed to become not only the founder of a new monastery, but he was also a well-to-do investor, who had once put a great sum of money into the account of a company in those times. Later, he was tonsured in his own monastery and labored within its walls more than any other monk. He managed to place a more solid foundation than silver coins—one built by his prayers for all those who lived at that place and those who would come there after his death.

This is why the misperceptions about the monk and founder were very soon defused, as miracles began to happen by his tomb—which, as they believed, was placed in the monastery out of gratitude for his charitable donations...

***

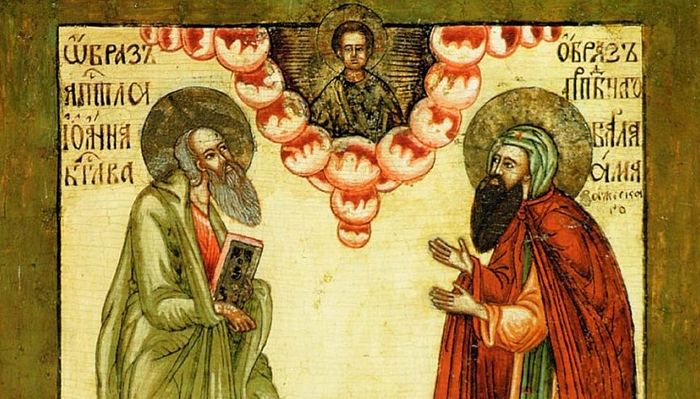

Holy Apostle John the Theologian and St. Varlaam of Vaga

Holy Apostle John the Theologian and St. Varlaam of Vaga

Basil was born to the family of a rich Novgorod boyar; in his “wealth and honor he was greater than his peers.” Noting his rank as mayor, the hagiographer writes that this was not really factual: “They say that he was a mayor of the great city of Novgorod.” However, due to the confusion of the times, it does not seem possible to dispel the rumor. And who knows? This may be actually true. Anyway, we can say that Basil was not short of money or administrative powers. Carrying out his duties of mayor, which meant being in charge of the city’s public assembly (Novgorod was at those times the Novgorod Republic), Basil was a wealthy landowner as he and his family owned vast lands with both real estate and other property, and lands in one of the five Novgorod regions. “When the family was dividing their lands, Basil the Mayor inherited the land named Zavolochiye, with the long Vaga River and all its tributaries in his possessions.” While managing state affairs in the capital, Basil did not forget to take care of his lands outside of the city, “To this place, in Zavalochiye, he sent his loyal servants to build up and manage his lot.” Moreover, he soon realized that this “lot”, located far from the city of Novgorod, would enable him to preserve his vast benefits and privileges, which would soon disappear when Moscow and its nobility would seize power.

Obviously it was a long time yet before Ivan III would undertake his military expeditions,1 but the wind of change, blowing from southeast [that is, Muscovy], clearly showed where the balance of history would shift. In general, Basil understood, realized, and felt that his rule in Novgorod was nothing but the end of what would become the “great prologue to a new historical play”. This is an undoubted fact that has been discussed in history books many times—that the lower classes living in cities and towns were historically very positive towards Moscow dominance, while the oligarchic boyars, wanting to preserve their ancient republic, to the contrary strove by all possible means to delay their submission to Grand Prince of Moscow. Being one of this political elite that did not wish to merge with the many vassals of Moscow, Basil preferred to be the poorest countryman in the Novgorod lands than a prominent politician in a Novgorod subdued by Moscow. Thus, when the political picture was quite clear, Basil left the banks of the Volkhov River [that is, Novgorod] to found his own palace “in Zavolochiye, on the top of a hill at the end of the great Vaga River, on the river called Pinezhka.”

Having come to the banks of the Vaga, Basil founded a new town. The hagiographer does not explain why Basil chose this place. While the new town was being built, Basil was still the mayor. But as years elapsed, it became more and more burdensome to govern Novgorod, it being a zone of political turbulence. The only consolation and, possibly, the final argument in favor of leaving his home city was the opportunity to give money for charity.

Basil’s humanitarian work as a prominent political leader in Novgorod was nothing like that of the usual boyar, who although possessing great wealth gives only rarely to chance paupers along his way. No, the Novgorod mayor had a thoroughly worked out system of charity to the most economically vulnerable groups of people. “Having absolute love for the poor, like the righteous Job, he was a defender of widows, a father for orphans, a helper of the poor, a provider of clothes for the naked, and a visitor to the ailing; he was full of mercy, and as they say, no one left his home with empty hands.”

This total generosity was characteristic of Basil throughout his life. This difficult manner of life finally came to an end when the weary mayor “left Great Novgorod, taking his wife and children, because of the numerous military invasions to which Novgorod was subjected.”

The town he founded on the bank of the Pinezhka was neither the place of his involuntary surrender nor the final abode of a politician exhausted by a long battle. From beginning to end this was his brainchild, which he intentionally created according to a fixed plan—mapping out streets, and building his palace. Every decision and every step was guided by a premeditated plan.

All these energetic activities were combined with rigorous spiritual labor—prayers at night and fasting—as if the high-ranking nobleman were still looking for answers to the important questions of his life. “It was the blessed one’s habit to spend the night in vigils and prayer on all feast days of the Lord and saints.”

The mature lord, who had already passed the apogee of his life, began a painstaking search for meaning. His broad life experience, numerous impressions and meetings with people of all social classes and occupations, nationalities and ages, the whole kaleidoscope of people and events from his youth to middle age, left Basil with a feeling of pathetic incompleteness... What was he missing? What could compensate for the oppressive emptiness? The answer soon came.

***

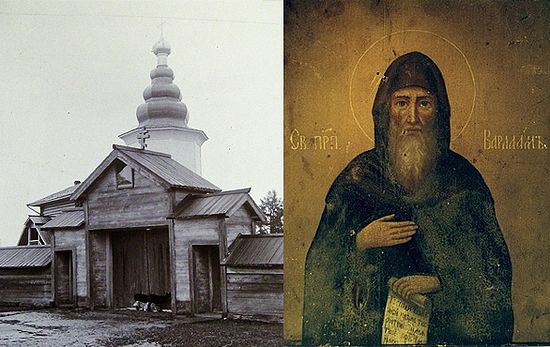

The chapel of St. Varlaam of Vaga, at the village of Smotrakovskaya (called Bogoslovskaya before the revolution), Shenkura region, Archangelsk province. May 26, 2013. Photo: temples.ru

The chapel of St. Varlaam of Vaga, at the village of Smotrakovskaya (called Bogoslovskaya before the revolution), Shenkura region, Archangelsk province. May 26, 2013. Photo: temples.ru

During one of his prayerful vigils, on the eve of the commemoration day of St. John the Theologian, Basil heard “a church bell ring from outside and reaching him”. The ringing and chanting, which could be heard throughout the night, came from a precise location: “By the town’s western part, within two gunshots of the river called Pinezhka”. The mayor realized that it was a sign that he should not overlook, but should at least build a church dedicated to St. John the Theologianat the place where the ringing was coming from. “After the dawn broke and daylight flooded in, the blessed one headed to see the place where the ringing and chanting could be heard.”

In the area to which Basil came, guided by the grace-filled ringing, there were two meadows fit for the construction of a church—one to the east and another to the west. The distance dividing the two meadows could be approximately measured as a “stone’s throw apart,” but Basil had to choose only one of them. This was not insignificant, as each scrap of land where a church is built is of the greatest spiritual importance to the founder’s contemporaries and descendants.

Basil was inclined to choose the eastern part as its ground seemed more solid and suitable for building a church. The Pinezhka floodplain lay close by, and the river, usually quiet and rather shallow, could significantly damage the future monastery should it flood. But the building of a church has always been considered a work of God and not of man, and thus rational reasons had to give place to reasons of a supernatural nature. As Basil never found a spiritual or clairvoyant person to consult, yet the choice had to be made, he decided to cast lots. Three times the lot was cast in favor of the western part, so Basil resolved to build the church on that place, and that would be the place where the priests and monks of the new monastery would live.

The St. John the Theologian-St. Varlaam of Vaga Monastery. Photo from the 1930s. Basil generously gave his money to build the monastery and arrange its economic life for many years to come. Besides the St. John the Theologian Church, he constructed another one dedicated to the Three Holy Hierarchs (presumably, to commemorate his heavenly patron, St. Basil the Great). The assiduous founder granted the monastery “vast lands that would provide its numerous monks with food”, sealing his gifts with “eternal certificates”. Basil insisted that the monastery adopt rules of coenobitic monasticism. Soon God-loving brothers assembled at the St. John Monastery, and the community with its spiritual warriors took up the warfare that is not against flesh and blood, but against “spiritual wickedness in high places”.

The St. John the Theologian-St. Varlaam of Vaga Monastery. Photo from the 1930s. Basil generously gave his money to build the monastery and arrange its economic life for many years to come. Besides the St. John the Theologian Church, he constructed another one dedicated to the Three Holy Hierarchs (presumably, to commemorate his heavenly patron, St. Basil the Great). The assiduous founder granted the monastery “vast lands that would provide its numerous monks with food”, sealing his gifts with “eternal certificates”. Basil insisted that the monastery adopt rules of coenobitic monasticism. Soon God-loving brothers assembled at the St. John Monastery, and the community with its spiritual warriors took up the warfare that is not against flesh and blood, but against “spiritual wickedness in high places”.

Here Basil realized that the vainglorious ambition to outdo all his political rivals and secure certain benefits or prerogatives—like free trade with the Hanseatic League or some sort of cultural uniqueness for “his” city, region or republic—was nothing but rubbish compared to the eternal battle between good and the evil, and the most important and useful weapon in this battle has always been prayer. Basil found his only consolation in the zealous building of churches. One by one, new churches emerged on the banks of the Vaga, with their foundation stones laid by the energetic boyar: churches of the Nativity of Christ, the Nativity of the Theotokos, and the Nativity of John the Forerunner. Moreover, Basil did not restrict himself to erecting only church walls—he hired iconographers to create magnificent interiors and bought service books from learned monks.

The nobleman’s soul was exultant—the liturgical life launched in the monastery by his authoritative hand ran like clockwork. The monks read canons and celebrated the Liturgy, and the Psalter reading never ceased there. The elderly priest never wearied in his prayers, while the younger monks hastened to relieve him after his daily labors. But while one prays, another chants, and another labors, yet another glorifies God and His angels, Basil scarcely who they were as he took care of everything so that others might chant, pray, or light the lampadas before the icons...

In these churches did Basil honor the Nativity of Christ, of His Mother, and of His glorious Forerunner, as though he were preparing himself for another nativity, another passage from shadowy nothingness into real life. Thus, the former mayor Basil died, and became the simple monk Varlaam. The monastery’s founder became one of its monks. The fact that all future generations of monks easily overlooked his podvig is the clearest testimony to the fact that after his tonsure, Basil rejected all his wealth and honor and completely changed his way of life. The poor monk Varlaam seemed so ordinary among the brethren, so willing to forget his prominent position and contribution to the monastery that everyone else who should have kept this in mind forgot about it as well.

The hagiographer speaks only briefly about Varlaam’s monastic life, but his description is vivid: “He waged a severe war with the devil, pleasing God with fasting and prayers, outdoing everyone in humility and submission. Thus, he made sure that he was one of the poor—neither the head of the monastery nor the governor of great Novgorod.” The venerable saint spent the last six years of life as a monk.

His soul’s intimate conversation with God, and how he conversed, is something that Basil-Varlaam took to his grave. But that the Lord answered his prayers became clear almost a hundred years after his repose. When the Pinezhka River flooded its banks, it eroded the monastery’ cemetery, washing away a number of coffins, and one of them was Varlaam’s. The saint’s relics were shown to be incorrupt, and were then reburied by the altar of the Church of St. John the Theologian. When ailing people began to turn to the saint in prayer, asking for his intercession, their diseases disappeared, and demons were forced to flee at the power of the righteous man’s intercessions. The local peasants understood that they had found a spiritual patron and merciful intercessor in the venerable founder, and the monks began to view their monastery’s history from a different perspective. Thus, the mayor Basil, whom it was said the monks had depicted wearing a hair shirt simply out of sycophancy, became for all an ascetic and true, humble monk.