Uzun Memetoglu and His Two Wives

Uzun Memetoglu was a wealthy crypto-Christian with many people under him, but was nevertheless just and generous. He and his wife had six children: Yiannis, Polychronos, Papastathios, Isaak, Abraham, and Agapi. In 1835, an Ottoman hodja who respected him very much, offered his daughter as a second wife. Memetoglu was forced to accept her as the girl was brought to his home when he was away in Trebizond, and sending her back was inconceivable once she had “sat there.” Refusing to father her children would also have been very dangerous for the crypto-Christian community if she had complained to her relatives, so he created a second home and had a son, Husein, and a daughter, Aise, by the hodja’s daughter. His wife never realized that he was a crypto-Christian, nor did Memetoglu try to convert her to Christianity, fearing that she might tell her Muslim cleric father. They lived like this until the official revelation of the crypto-Christians. When Memetoglu revealed his Christianity, the Turkish girl could not bear the thought of becoming a Christian and went back to her father, taking the children with her. Fifteen days later, the children returned to Memetoglu and became Christian. The number of people in Kromni related by marriage or through a spiritual relationship was remarkable. Every baptism gave the child’s parents a dozen new relatives from the godparents’ families. This spiritual kinship was considered sacred and was added to exponentially when the same godparent stood as godparent to another child. With weddings, also, one made an “army” of relations by marriage, not to mention the families of one’s koumbaros and koumbara (best man and bridesmaid). In the crypto-Christian community, all of this was managed discretely and with such order that it is a wonder how so many people managed to conceal such a great secret for over 200 years, taking into account human weakness, jealousy, and the reprisals that are part of everyday life. The fact that so many thousands of people guarded this secret as the apple of their eye, in the fear of God, is astonishing.

The crypto-Christians made up various ruses and pretexts to avoid match-making Ottomans who might ask for their daughters. Even one girl given to an Ottoman family was considered a tragedy, as the girl then belonged to the family of the groom and would become a Turkish Muslim. On the other hand, the crypto-Christians never rejected an Ottoman bride for their sons. In cases where the matchmakers brought an Ottoman bride into the house of a crypto-Christian family, the girl would be isolated by the bridegroom’s sisters and her mother-in-law, and not allowed to share her husband’s bed until she was catechized and had agreed to become a Christian. Only after her baptism could she be married in a Christian service and come together with her husband.

Traditionally, girls only returned to visit their parents after a year of marriage, and there were virtually no cases of Ottoman brides betraying the secret to their parents. Compared to her Muslim home, the new Christian family was usually less strict and the girl would keep quiet about the new family’s Christianity out of love for her husband and respect (or fear) of her she had complained to her relatives, so he created a second home and had a son, Husein, and a daughter, Aise, by the hodja’s daughter. His wife never realized that he was a crypto-Christian, nor did Memetoglu try to convert her to Christianity, fearing that she might tell her Muslim cleric father. They lived like this until the official revelation of the crypto-Christians. When Memetoglu revealed his Christianity, the Turkish girl could not bear the thought of becoming a Christian and went back to her father, taking the children with her. Fifteen days later, the children returned to Memetoglu and became Christian.

The number of people in Kromni related by marriage or through a spiritual relationship was remarkable. Every baptism gave the child’s parents a dozen new relatives from the godparents’ families. This spiritual kinship was considered sacred and was added to exponentially when the same godparent stood as godparent to another child. With weddings, also, one made an “army” of relations by marriage, not to mention the families of one’s koumbaros and koumbara (best man and bridesmaid). In the crypto-Christian community, all of this was managed discretely and with such order that it is a wonder how so many people managed to conceal such a great secret for over 200 years, taking into account human weakness, jealousy, and the reprisals that are part of everyday life. The fact that so many thousands of people guarded this secret as the apple of their eye, in the fear of God, is astonishing. The crypto-Christians made up various ruses and pretexts to avoid match-making Ottomans who might ask for their daughters. Even one girl given to an Ottoman family was considered a tragedy, as the girl then belonged to the family of the groom and would become a Turkish Muslim. On the other hand, the crypto-Christians never rejected an Ottoman bride for their sons. In cases where the matchmakers brought an Ottoman bride into the house of a crypto-Christian family, the girl would be isolated by the bridegroom’s sisters and her mother-in-law, and not allowed to share her husband’s bed until she was catechized and had agreed to become a Christian. Only after her baptism could she be married in a Christian service and come together with her husband.

Traditionally, girls only returned to visit their parents after a year of marriage, and there were virtually no cases of Ottoman brides betraying the secret to their parents. Compared to her Muslim home, the new Christian family was usually less strict and the girl would keep quiet about the new family’s Christianity out of love for her husband and respect (or fear) of her parents-in-law. Also, she knew the penalty of conversion: her husband’s family would be arrested and executed, and she would be a social outcast, humiliated for the rest of her life. In only one case did an Ottoman girl married to a Kromnean reveal the secret. Aziz Agha, the son of Mourteze Effendi, married a Muslim bride from Keleverik of Ispir, near Kars. After she was catechized, Aziz Agha took her to the Monastery of Panagia Soumela to be baptized, where she was christened Sophia. After some time, Sophia visited her family and was foolish enough to tell her parents everything that had happened. The case was taken to Argyroupoli, and the Christian family was saved only by the testimony of an old Armenian woman named Afitap, who claimed that Mourteze Effendi was such a pious Muslim that he had forced her to become Muslim. With her accusation a very different picture appeared: that of a Muslim so faithful that he had forced an Armenian to become Muslim herself. It was a lie, of course, and it was also likely that Mourteze Effendi’s family bribed the Ottoman judges, who finally ruled that this was a family squabble and outside of their jurisdiction. The secret of the crypto-Christians was saved. However, the Islamic clergy must have suspected something because during Ramadan they sent a high-ranking muezzin to guide the Kromneans on how to keep the fast and say their prayers. To protect themselves from suspicion, the Kromneans decided to build a mosque, which was finished in 1815.

Mullah Molasleyman’s Daughter

Hagia Sophia Church, Trabzond. Now a museum.

Hagia Sophia Church, Trabzond. Now a museum. One of his greatest trials, however, was his own daughter, Gülbahar. Truly, he lived through an adventure with her. Gülbahar was born in Varenou in 1784, baptized with the name Maria, and died in Trebizond in 1864. At the time of this story she was twelve years old.

Throughout his life, Mullah Molasleyman had had an Ottoman friend, Said Agha, a very good and wealthy man from Loria of Kromni, who deeply loved and respected the mullah. Each time the mullah went to Loria, he stayed at Said Agha’s house, and after dinner, the agha would listen as he read the words of the Prophet from the Koran. When the namaz (prayer)was finished, Said Agha would ask for an explanation of the scriptures, which the mullah gave in Pontian because Said Agha did not speak Turkish. His grandfather’s grandfather had come to Kromni and put down roots, and now they were Greek-speaking Kromneans.

Likewise, when Said Agha came to Varenou he was a guest of the mullah, but in either case, eating with a Muslim presented a problem, for how could the priest eat without praying, or at least making the sign of the Cross over his food? Mullah Molasleyman, however, had devised his own solution. Before beginning he would say: “My head will think, my stomach will eat, my right and left side will be satisfied,” and, as he spoke, he made the sign of the Cross. At the end of the meal he would again cross himself saying, Yedim basim icin, kizdim kanim icin, hem saga, hem sola, hem nihahyet canima. “My head ate, it reached my stomach, my right and left side, and also my soul.”

In February 1796, Said Agha came to Varenou and, as usual, visited his friend the mullah, planning to ride back to Loria in the evening. A sudden snow-storm arose, however, and the mullah could not allow his friend to leave in such bad weather. Said Agha would, of course, stay the night.

The timing, however, was deplorable. The mullah loved Said Agha and respected him as a fair and God-fearing man, but how unfortunate that he had to stay in the middle of Great Lent! He was obliged to honour Said Agha in the same way that the mullah was hosted in Loria, but what food could he offer him? His household kept the fast with great austerity and no deviation could be justified. Nevertheless, they cooked for Said Agha, and the pans that had been thoroughly cleaned on Clean Monday for the fast were spoiled by cooking non-Lenten food. Fortunately, the guest would dine alone with the mullah, for in an “Ottoman” household, other family members, particularly women, had no place at the table with male guests. The mullah pretended that he had a stomach ache and only drank tea.

When guests arrived, only the older women were allowed to appear with their faces veiled. The children remained in another room, unseen. Despite these injunctions, twelve year-old Gülbahar could not help glancing in as she passed the door, and Said Ahgha, noticing her poised, statuesque air, reflected on what a wonderful bride she would be for his 18 year-old son, Husein. A beautiful girl, and her father the mullah, a dear friend. In the morning, when the weather cleared, he left for Loria.

At the end of April, as the snow began to melt, Said Agha sent his men on horseback for an old and respected matchmaker, Fatme of Mohore, who had arranged many of the Kromnean marriages. (She was also a crypto-Christian, baptized with the name Paresa.) When she arrived with the agha’s escort, Fatme was welcomed with great honor. Used to such receptions, she was nonetheless curious as to what match this was leading to, and when she understood that Said Agha wanted the mullah’s daughter as a bride for his son, she was horrified. It was impossible for Mullah Molasleyman to give his daughter to an Ottoman. “His daughter is young,” Fatme protested. “It does not matter,” said the Agha. “She is twelve years old. We can have the betrothal now and the wedding in one or two years.” Forced to agree so as not to arouse suspicion, the distressed matchmaker could only think of one thing to gain time, “Said Agha, I will not be able to go to the mullah right away because my mother-in-law is dying, but I will go when I can and will bring you the answer.” Said Agha filled her bags with gifts and money, and his men escorted her home.

When she arrived home, Fatme slipped off the horse, dismissed Said Agha’s men and prepared to leave immediately for Varenou. Her son said, “Mother, you’ve just come and now you are going again?” “It’s big trouble, my son,” said Fatme, as she rode away.

In Varenou she went straight to the mullah’s house where she was welcomed by his wife and daughters, excited at the prospect of a marriage offer. The mullah was not at home and Fatme told them to run and bring him quickly. When the mullah arrived, she exclaimed: “Father, a great calamity has come upon our heads! How did you let that dog, Said Agha, see your Gülbahar? He has asked me to mediate so that she will marry his son. I couldn’t tell him it was impossible, all I could do was to lie to gain a little time. I told him that my mother-in-law was dying.” “You did very well,” said Mullah Molasleyman. “Go back to Mohore and I will find a solution.” That night, Mullah Molasleyman could not sleep. He loved and respected the agha. He could not give him his daughter, yet how would he justify his denial without offending his friend? By dawn he knew. It was an unorthodox solution, but a saving one.

After drinking his morning coffee, the mullah told his wife to send one of their boys to find Murat Yiazitsi Zade, a distant relative and poor farmer with many children, to whom Mullah Molasleyman had always extended timely help. The snow had already melted and Murat, in the fields since dawn, arrived embarrassed and dirty from his work. The mullah, however, welcomed him warmly and led him upstairs. He explained his dilemma and said, “What I am telling you is a shame for me, but this shame is nothing compared to the sin of my daughter becoming a Turk. Nevertheless, we are relatives, and if you do not agree to my proposal, everything we say will remain only between us. “Curious and embarrassed, Murat wondered how he, poor and illiterate, could be of assistance to the mullah and priest.

The Mullah said, “Murat, you have a son named Tursun, the one we baptized as Kyriakos. Will you take my daughter Maria as a bride for Kyriakos? The extraordinary offer struck Murat like a thunderclap, but the mullah continued, “I know that grooms propose to brides and not brides to grooms, but in the face of such danger to my daughter, I don’t believe this deviation is wrong.”

Murat was astonished at being asked to accept the mullah’s daughter into his house, and with joy replied, “What shame are you talking about, Father? It is a great honour for us to accept your daughter as our bride.” “Since you agree,” the mullah said, “come and make the offer, and on Sunday we will have the Soumadema (the Betrothal). No one must ever know what we have talked about today.” The same evening Murat and his wife visited the mullah’s family and asked for Gülbahar. This is how the match-making of Gülbahar (Maria) and Tursun (Kyriakos) Yazitzi Zade came about in April of 1796.

Fatme sent the news of the engagement to Said Agha, that unfortunately someone else had asked for Gülbahar first. The agha was sad, but what could he do? He blamed himself for not having arranged the matter earlier. Tursun and Gülbahar married in Varenou when he was seventeen, and she, thirteen. They had many children, one of whom was Hadjimurat Yiazitzi Zade, born in 1807, who later became a merchant. (Their Greek family name afterwards was Grammatikopolous, but they went by the Turkish family name, Tursunand.) Hadjimurat married Sophia Koukou in Tapezounta, and one of their many children was Tursun (Kyriakos) Yiazitzi Zade (named after his grandfather), who was born in 1844, and was 13 years old at the time of the Hatti Humayun, which guaranteed Turkish citizens freedom of religion. Kyriakos married Maria Ephtichidou, with whom he had three boys and four girls. One of the girls was my grandmother Aphrodite.

Folk Beliefs: Comets and Hortlaks

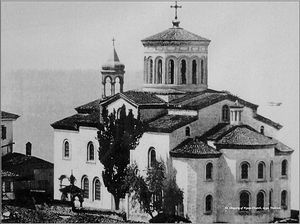

St. Gregory of Nyssa Church, Trabzond

St. Gregory of Nyssa Church, Trabzond Another tradition of the area was the Hortlak, which means “ghost.” The people of Kromni believed that anyone who died without paying his debts could not rest in peace, and at night would arise from the grave, crying and shouting, until his family paid what he owed. After the debts were settled, the priest would do a small service or read prayers over the grave.

Hearing these stories from Aphrodite, it seemed peculiar to me that the most common Hortlak were Ottomans, and at night everyone could hear their deceased Turkish neighbor shouting as a Hortlak. The Ottoman relatives listened to these stories and after some time they themselves began hearing the voice of their dead, after which they quickly settled the debts. I believe that this was a clever trick of the Christians to make the Turks repay their debts, but when I asked Aphrodite, she emphatically answered in the negative. She insisted that the Hortlak existed and they could be either Christian or Turk. Christians, also, who left unsettled debts to either Christians or Turks could not rest until they were settled. It was divine justice demanding recompense, she believed, not a trick.

Another peculiarity was that even the Turkish Muslim families took an Orthodox priest with them to the Muslim cemeteries for a short prayer service over the grave after the debts were paid. Pontians believed these stories and if an Ottoman consulted his Muslim mullah about it, he was assured that the Hortlak really did exist. People not only heard, but saw them, and for this reason no one ventured out after dark without good reason. And no one ever went near a cemetery at night.

Crypto-Christian Burial Practices

There was also, for us, the humorous and long-standing belief of the Turkish Muslims in the surrounding areas that the air of Kromni was very good because no one ever died there! This was because the crypto-Christians held their funerals after dark in their house chapels. In the countryside, people had (and still have) the legal right to bury the dead on their own property, so in Kromni, the crypto-Christians were buried with Orthodox rites in their own gardens. Muslim outsiders never saw the burial services.

In larger towns or cities, however, this wasn’t allowed, so they had to bury the supposed Muslims in the Muslim graveyard. In the Muslim community were specialists who prepared the body for burial, and it would have been suspicious if a family did not call them or refused to follow Muslim burial practices. As part of the burial service, Muslims wash their dead in extremely hot water, hotter than anyone living could bear.

This presented a problem for crypto-Christian men because of the tradition among Muslims of circumcising their young boys.[1] Muslim attendants preparing the body of an uncircumcised crypto-Christian man for burial would immediately understand that this man had been a Christian. Instead, the crypto- Christians in the cities often used an alternative Muslim funeral custom called aptest, when, immediately after death, they sewed the body into a white shroud which was not opened again. Instead of a funeral casket, there was a wooden bier. The dead person was placed upon the bier and taken to the porch of the mosque, where he was positioned with only his feet in the entryway – his head pointed outwards. They recited the prayers and verses from the Koran and then buried the shrouded body directly in the earth.

Traditionally, girls only returned to visit their parents after a year of marriage, and there were virtually no cases of Ottoman brides betraying the secret to their parents. Compared to her Muslim home, the new Christian family was usually less strict and the girl would keep quiet about the new family’s Christianity out of love for her husband and respect (or fear) of her she had complained to her relatives, so he created a second home and had a son, Husein, and a daughter, Aise, by the hodja’s daughter.