Mother Veronica has led her monastic life at Holy Ascension Convent on the Mount of Olives [Eleon] since 1956. Having arrived here as a little girl, she decided to stay here the rest of her life. Her Arabic heart not only preserves devotion to Christ, but love for Russian history and culture. Her years on the Mt of Olives have been spent in prayer, fasting and vigils among the nuns of various nationalities, and the monastery’s grace and atmosphere of beauty are palpable during the monastic services, filled with a special, prayerful spirit.

* * *

—Mother Veronica, they say that you found yourself in this convent as a little girl and refused to leave for any reason, despite the tears and exhortations of your relatives.

Yes, I came to our Ascension Convent as an eight-year-old girl. I knew three prayers in Russian pretty well already: Our Father, the Trisagion and Lord Have Mercy. I had learned them in my native town of Bethlehem, from which exactly 55 years ago my grandmother Aziza and I came to Eleon. I remember the date—it was March 2, 1956.

Our Arab family had Greek roots, and the surname Raheb means “monastic” in Arabic. My parents’ house in Bethlehem was next to the Basilica of the Nativity of Christ, where I was baptized. And so it happened that when my parents divorced, my grandmother reared me until I was eight. She had at one time attended a Russian school for Arab children in Beit Jalla; there we would attend services in Orthodox churches. My grandmother had loved the Russian people since her childhood, and could communicate fairly well in Russian. She was the one who first taught me my first Russian words and prayers.

Russian nuns from the Mount of Olives frequently stayed at our house when they would visit Bethlehem on big holidays. Nun Tatyana, whom my brother Ilia and I called our “Russian grandmother” would visit. Ilia was killed at the front in Jordan when he was 23 years old. Our father was in the military, and in 1956, my grandmother had to go see him in Kuwait, where he was posted at the time. That was when she brought me to the convent, “only for a couple of months,” and as it turned out, for the rest of my life.

—Was Mother Tamara the abbess of the convent at that time?

Abbess Tamara Yes, Matushka Tamara, renowned in Tsarist Russia as an Imperial Duchess, was the daughter of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich and of Grand Duchess Elizaveta Mavrikievna, and great-granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I. She was born Tatiana Konstantinovna Romanova. Her helper in those days was an Arab, Nun Feoktista, and in 1948, came along with the other sisters from Gorny Convent to Eleon. There were 130 aging nuns living there then, among them three Arab girls who later became Nun Rafaila, Nun Christina and Nun Maria. Matushka Tamara knew my grandmother Aziza well. In Bethlehem, my family lived comfortably, being the owners of land and an olive plantation. Grandmother often visited the Convent on Eleon, and always brought gallons of olive oil for their icon lamps as a gift.

Abbess Tamara Yes, Matushka Tamara, renowned in Tsarist Russia as an Imperial Duchess, was the daughter of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich and of Grand Duchess Elizaveta Mavrikievna, and great-granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I. She was born Tatiana Konstantinovna Romanova. Her helper in those days was an Arab, Nun Feoktista, and in 1948, came along with the other sisters from Gorny Convent to Eleon. There were 130 aging nuns living there then, among them three Arab girls who later became Nun Rafaila, Nun Christina and Nun Maria. Matushka Tamara knew my grandmother Aziza well. In Bethlehem, my family lived comfortably, being the owners of land and an olive plantation. Grandmother often visited the Convent on Eleon, and always brought gallons of olive oil for their icon lamps as a gift.

I remember when my grandmother and I first arrived, they gave me a Russian grammar book and a gray cassock, being the littlest girl. And so two months passed, grandmother returned to Bethlehem, and then came to Eleon to collect me. But I refused: “Babushka, what is this? I am already a nun! I am studying Russian here. An Arab tutor comes. I eat Russian borshch and kasha, I like it…” Hearing this, grandmother smiled but her eyes were filled with tears: “I can’t leave you here, you are little. What will your father say?” I burst out in tears, too, and ran to Abbess Tamara. Matushka tried to persuade my grandmother: “Leave her for a little while, and then we’ll see. She has everything she needs here, she is studying Arabic and Russian…”

I remember that my 80-year-old grandmother came to fetch me two more times. Of course, tears flowed and arguments were made, but I did not leave the convent. My relatives “hunted” me until I was 25, even my mother came, but all for naught.

Of course, my father also came to retrieve me, but Matushka Tamara would implore him: “Elena (that was my lay name) already sings on our kliros, she knows music, she learned to sew…”

I had the widest variety of obediences: I sang, I made candles, I knitted prayer ropes, I helped in the iconography studio. Matushka Tamara herself taught me Russian and the craft of sewing, while Matushka Feoktista taught me embroidery. My education took place in the Abbess’ quarters under her supervision. For 25 years I never left her side—until her death.

—How many years did you spend at the convent before you were tonsured?

—Everyone told me that as children, girls should play with dolls, and not rush to be a nun. Of course, being naive, I pushed everyone to dress me as a nun when I was only 9 or 10. Once I approached Matushka Tamara (out of earshot we called her “ama,” which means “mama” in Arabic), and I asked her when I would finally become a nun. She caressed my head in a motherly way and said: “It’s too early for you, you are nothing but a girl.” I almost burst into tears from the insult, I so wished to be an adult! Afterwards, Matushka Tamara gave me a big doll, while in return, secretly from everyone, I sewed a complete monastic outfit for it. I showed it to her, and pleadingly, but with a note of cunning, said: “Here you go, even my doll Tatiana has already been tonsured, but I’m still waiting…”

“Ama,” looking at the doll garbed in black, only smiled, then called Sister Susanna, who was the tailor to all the nuns, and asked her to sew me a white monastic headcovering called the apostolnik: “Let’s begin with this…”

Since my childhood I came to love everything Russian, and even “God’s kasha” and various borshches. Though an Arab by nationality, in my consciousness I always felt Russian. That’s what they called me: “An Arab woman with a Russian soul.”

I became a novice on the feast day of the Ascension of the Lord, and a nun on the Akathist of the Theotokos. My full tonsure occurred on the eve of the feast day of the Beheading of John the Forerunner.

Archimandrite Dimitry (Biaka) tonsured me a novice, Archimandrite Anthony (Grabbe) tonsured me as a nun. I was tonsured at the age of 33, and I remember being the youngest nun. So my time at the Mount of Olives lasted over a half a century. I have spent my whole life here, never leaving, never even having a thought of wandering from monastery to monastery or to resettle in another one.

—So even in your childhood you never attended an Arab school, and learned Russian by yourself in the convent?

– An Arab teacher would come to us twice a week. True, she would complain to the Abbess about me--that I didn’t want to study Arabic. I relished studying Russian grammar and conversational Russian. Of course, I also learned English. But I especially loved Russian history and literature. Together with the older Arab girls I would learn Russian sporadically, but in the early 1960’s, Evgeniya Kleptsova arrived at our convent—she was the spiritual daughter of St John of Shanghai, then-Archbishop of Western America. Later, our teacher became Nun Juliania. She gave us a serious education in Russian. We had difficulty with the stressed syllables and written dialog. We needed good textbooks, so our teacher ordered them from her sister, who lived in Moscow. We received two books by mail in a couple of months. Of course, these textbooks were infused with the Soviet spirit and its ideology: Octobrists, Pioneers and Lenin were there throughout the texts. All the propagandistic sentences and disturbing passages were censored by Nun Joanna, mercilessly blotting them out with black pencil or ink. We children were intrigued: what is hidden underneath this blackness, on ruined pages? One day we sinned, having played a prank on our teacher. She was passing by one of our windows and we instantly seized a glass and a writing pen and began drumming on it, reciting the words “We are children Octobrists!” The nun sat down in horror: how could anyone say such things in a convent?! Of course, later, we confessed that sinful prank to our priest.

—Who taught you Russian history at the convent?

– The Law of God and history were taught by Archimandrite Dimitry, who was then the Chief of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission of the Church Abroad. He had a rare intelligence and memory, and an inexhaustible energy. He had the gift of tact; he knew all the sisters by name and did not favor anyone. Fr Dimitry had a profound knowledge of the Old Testament and New Testament traditions, the history of Palestine and was a splendid teacher at the convent. He loved Russia a great deal, telling us a great deal of what he knew and often remembering the Kievan Lavra of the Caves, where he was tonsured to the monkhood.

I always loved studying Russian history, since its earliest period, the Rurik Dynasty. I studied so hard in this subject that I would win competitions among the best history students, which were organized by Fr Dimitry. From his hands I received a little icon, sometimes cloth and thread for embroidery, or a new cassock or riassa, and once he even gave me a tape recorder. Once I was an expert in Biblical history and was able to list the names of all the pharaohs and Biblical kings. But I was also drawn to classical Russian literature. I particularly liked the religious poetry of Pushkin and Lermontov. I almost memorized all of Eugene Onegin. I had some difficulty [laughing] reading Gogol’s Dead Souls, but appreciated the books of Dosteovsky and Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

—You were probably also familiar with the poetry of “K.R.”?

—But of course! Matushka Tamara dearly loved her father, Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, who wrote under the pseudonum “K.R.,” though she spoke very little about her own life while in the monastery. She had a small collection of her father’s poems, and she often gave me “K.R.’s” poems to learn by heart for Pascha, the Ascension of the Lord or her namesday. Princess Vera Konstantinovna came to Eleon a few times, the younger sister of our Abbess Tamara. We really loved her, we called her “generous, caring but strict Aunt Vera.”

When the sisters sank into their reminiscences, then I would read their father’s poems at Matushka Tamara’s request. If I hesitated during the reciting of a poem, Vera Konstantinovna would pick up where I left off. Then I would remember and continue myself.

—How do you remember Matushka Tamara?

Matushka Tamara and her sister, Vera Konstantinovna. —I first met her on March 2, 1956, when my grandmother and I first ascended the Mount of Olives. That day the convent was celebrating the “Reigning” Icon of the Mother of God. There was a procession of the cross with this image at the convent, along the inside of the walls. Archimandrite Dimitry and Abbess Tamara led it, and she was the one who later became my “ama”—my mother.

Matushka Tamara and her sister, Vera Konstantinovna. —I first met her on March 2, 1956, when my grandmother and I first ascended the Mount of Olives. That day the convent was celebrating the “Reigning” Icon of the Mother of God. There was a procession of the cross with this image at the convent, along the inside of the walls. Archimandrite Dimitry and Abbess Tamara led it, and she was the one who later became my “ama”—my mother.

Matushka Tamara and Her Sister Vera Konstantinovna

All of us sisters knew that Matushka Tamara was wholly devoted to monsasticism and in the difficult post-War years, she did a great deal to build up our convent. She never liked talking about her previous life. It was only later that we learned that she became Bagration-Mukhransky from her first marriage, then Korochentsova from her second. And if she did talk about her family, she would not say “my husband” but modestly “the father of my children,” who was in fact Prince Bagration-Mukhransky. She was the epitome of aristocracy, love and humility. Everyone who knew her personally noted that she possessed genuine simplicity and was the most revered of abbesses in Eleon. Her qualities of distinction were kindness, attentiveness, patience and love for her neighbor. She was highly regarded by many in the Holy Land. She strengthened the finances of the convent and brought in new residents. She was able to gain the trust of many local Orthodox Christians, thanks to which many wealthy Arab families began to send their girls to the convent for education, thereby bolstering our monastery financially. Matushka Tamara maintained the Russian spirit in the monastery and tried to give the Arab girls a Russian upbringing. She taught Russian to them personally, and Church Slavonic, as well as Russian literature. She did not distinguish herself from her nuns, and her meals were of the simplest kind—she would only use a single spoon during meals.

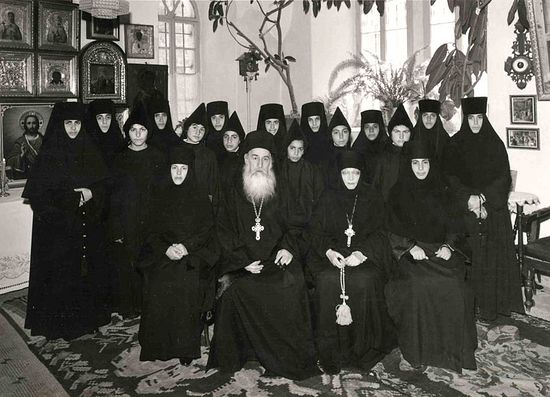

—Your convent is home to 16 Arab, 13 Russian and 7 Romanian nuns, but it remains Russian. Can you tell us about the nuns of Arab descent?

– One of the most renowned is, of course, our 89-year-old Matushka Feoktista (Yagnam). Since the age of 16, she labored at Gorny Convent, and since 1948, on Eleon. She hailed from a churchly and very prosperous Arab family. All of the flour the convent had was donated by her father, Thomas. He was a very churchly person and did a great deal of charitable work for the convent. Until 1965, he supplied our monastery with white flour of the highest quality. When he was building a church dedicated to St George over a cave on his property, he invited our nuns to paint its frescoes, so that their earnings could help the convent. Matushka Feoktista was very well educated, having attended college in Birzeit. In addition to her native Arabic, she spoke English and Russian. Her life was connected with Matushka Tamara, to whom she was very devoted. At the age of 24, Matushka Feoktista was the main helper of Abbess Tamara, and before and after her, to Abbess Paula, Feodosiya and Paraskeva. Maybe they didn’t really like this in the convent, but her magnificent knowledge of several languages, mainly Arabic, inclined her to this work. Neither Abbess Tamara nor Fr Dimitry spoke Arabic, while the official language of all civil institutions in the town of Atur, where the convent is located. Matushka Feoktista was a genuine, humble nun. She was also devoted to monasticism, and when she visited her parents, would still not leave the convent for more than two days. She never spoke of lay matters, never condemned anyone and if she ever spoke to a man, never looked him in the face. Despite her daily chores, she found time to give embroidery lessons and composed designs herself. She was an artist, too, having studied painting professionally. Now Matushka Feoktista has fallen to Alzheimer’s and she is in an Arab hospital on the Mount of Olives. She is bravely facing her sickness. She talks with us only on spiritual matters. She refuses to eat in the evening, only having a gulp of tea: “tomorrow I take Communion!” she says.

Our other Arab nuns came to Eleon from Bethlehem, Beit-Sahur, Ramallah, Taibeh, Beit-Jalla and even from Jordan. These include Sisters Afanasiya (Odeh), Tamara (Khoury), Rafaila (Lehl), Apollinaria and her sister Ekaterina, Christina (Dihab), Melania (Arikhani) from Jordan, Anastasia, Ioanna, who came to us from Gethsemane, Nun Vera and Nadezhda (Abouton), two sisters from Beit-Jalla, and my niece Matushka Rufina (Bandak), Sister Mastridia of Jordan, who leads the kliros singing and paints icons.

Our other Arab nuns came to Eleon from Bethlehem, Beit-Sahur, Ramallah, Taibeh, Beit-Jalla and even from Jordan. These include Sisters Afanasiya (Odeh), Tamara (Khoury), Rafaila (Lehl), Apollinaria and her sister Ekaterina, Christina (Dihab), Melania (Arikhani) from Jordan, Anastasia, Ioanna, who came to us from Gethsemane, Nun Vera and Nadezhda (Abouton), two sisters from Beit-Jalla, and my niece Matushka Rufina (Bandak), Sister Mastridia of Jordan, who leads the kliros singing and paints icons.

We all came to the convent to seek salvation for our souls. And we fought for everything Russian and of the Russian diaspora—I’m talking about the Russian Church Abroad. We took everything Russian into our souls and did not even wish to know anything Arabic. We sang on the kliros, where Nun Afanasiya was the choir director for 33 years. We could, but never wanted to, sing anything in Arabic, so as not to disturb the monastic rule.

—Now your obedience is to work in the souvenir shop, which many pilgrims visit every day. You probably have to answer many questions.

—Oh, yes! But even in the kiosk, just as in my room, I don’t drop the thread of prayer day or night. Many are interested in details of the history of our convent. The questions are of a wide variety, some are pretty difficult to answer. For example, pilgrims from the Ural region once asked me if Hegumen Seraphim (Kuznetsov, 1873-1959) once lived at our convent, the same one who brought the coffins with the relics of our new Russian saints, Martyrs for Christ Elizabeth and Nun Barbara, from Russian through Harbin. Everyone knows that it was Fr Seraphim’s accomplishment that these holy relics were found and preserved.

The late Mother Minodora (Chernova) would tell me that Fr Seraphim lived in our convent from the 1920’s until 1945 and was even its spiritual father for a time. A few nuns from the Urals came to him. But Hieromonk Seraphim did not get along with our convent leadership and was forced to move to Minor Galilee, located on the Mount of Olives. I won’t delve into the reasons for the conflict. Nearing the end of his life, he spent his time at the Monastery of the Holy Apostles in Minor Galilee, the residence of the Jerusalem Patriarchate. Fr Seraphim reposed in the Lord in that monastery in 1959, and his grave is there. His epitaph reads like an appeal to his compatriots…

I remember when I joined the monastery, there were nuns from their sixties to their nineties, many of whom came from the Urals. I think that Fr Antonin (Kapustin) was from that area, too. So word of our convent had even reached that far.

—You have probably had to tell other pilgrims and visitors about yourself, too.

—Of course, I end up saying something about myself. It’s a shame, though, that many of them thinking that we Arabs only came to Christianity at the convent—from Islam. They ask “Did they baptize you at the monastery? Was it long ago?” “No,” I reply, “I was baptized as an infant in Bethlehem, in the very cave where the Lord was born!”

I would even often meet priests who did not know, or could not understand that Christianity has been preached here, on Arab land, since the times of the Apostles, that the Holy Land is home to more than a few Christian Arabs. The only thing they have in common with their Muslim neighbors is their tongue.

The residents of the Arab town of Atour, where our convent is located, were also surprised at first that Arab girls were visiting a Russian convent. Then they grew accustomed to that, and understood that we were not Muslims but Christians. As a young woman I remember hearing that priests and pilgrims would ask our monastery leadership: why are you accepting Arabs into your Russian convent? The local Greeks rebuked our Fr Dimitry: “Why, without consulting us, are you accepting Arab girls from our parishes? These are the children of our parishioners.”

Fr Dimitry would respond: “But you didn’t open an Orthodox monastery for them, and so many of them come to us. Some even go to Catholic convents. Who will preserve Orthodox Christianity in the Holy Land?”

So there you are, we are preserving Orthodoxy on the Mount of Olives.

My years on the Mt of Olives have been spent in prayer, fasting and vigils among the nuns of various nationalities, and the monastery’s grace and atmosphere of beauty are palpable during the monastic services, filled with a special, prayerful spirit.

Dear Mother Veronica, 8-14-2011

I enjoyed reading about how you grow up in the

faith at the convent. I find it most interesting

after all this time, that there are some who wonder

why would any one from another race could belong to a

Church that to some seem so foreign to them. I can

understand that kind of thinking, and i can also relate

to what you said about this.I have been Russian Orthodox

for seven and a half years. Since that time learned some

Russian just a little. Other then my English and Spanish

Again it was a joy to read about you and the convent.

Yours, in Christ Ponomar Jose' Saint Innocent of Moscow

Russian Orthodox Church Carol Stream, Il.