Source: Apologia Pro Ortho Doxa

Following up on the link I posted yesterday, I thought it might be a good idea to introduce folks to the entire concept of chronological revisionism, why it matters, and what it means for the Bible. Most of us assume that we know precisely when historical events occurred in ancient history- after all, encyclopedias and textbooks list, year by year, the reigns of various kings and the dates of various battles. In reality, however, the situation is far murkier than this. In fact, the entire edifice of ancient chronology is built upon the reconstructed chronology of Egyptian civilization. All other civilizations are “keyed” into Egyptian history. I won’t go into the exact problems with Egyptian chronology at this moment, but mainstream Egyptologists have referred to it as “rags and tatters.” It maintains weight by force of simple consensus.

More importantly, though, what relevance does this have to the Bible? Well, in the conventional chronology, there is little more than circumstantial evidence for the exodus. James Hoffmeier and Kenneth Kitchen have argued for an exodus during the reign of Rameses II (13th century according to mainstream chronology). There are enormous problems with this identification. For example, it contradicts the biblical figure of 480 years between the exodus and the building of the Temple. Furthermore, we have Rameses’ mummy- he clearly didn’t pursue Israel into the Red Sea. Most importantly, however, we have these words from Pharaoh’s counselors:

(Exodus 10:7) Then Pharaoh’s servants said to him, “How long shall this man be a snare to us? Let the men go, that they may serve the Lord their God. Do you not yet understand that Egypt is ruined?”

The exodus and the plagues of Egypt were not minor events in the ancient world. If they occurred, they brought about the ruin of Egypt, probably for an extensive period of time.

The backbone of any revisionist chronology must be the destruction of Egypt.

The basic outline of Egyptian history by mainstream historians is as follows:

1. Old Kingdom.

2. First Dark Age

3. Middle Kingdom

4. Second Dark Age

5. New Kingdom

6. Sack of Thebes

As you can see, there are two dark ages here. Revisionists such as Donovan Courville have argued that the Old and Middle Kingdoms actually ran parallel to each other, and that the two dark ages ought to be identified. That’s neither here nor there at this point (though it will be). We only have to ask whether one of these ages corresponds with the events surrounding the exodus. And it does.

When Israel comes out of Egypt, in Exodus 17, they discover and fight a group of Semites called Amalekites- but why are the Amalekites there? In the second dark age of Egyptian history, a group of Semites called Hyksos invaded and quickly conquered Egypt, ruling brutally for several centuries until finally being expelled by Ahmose I (thus inaugurating the New Kingdom). Their brutality was legendary. Furthermore, Manetho, an Egyptian historian, records that in the reign of one of the last Middle Kingdom Pharaohs, Dudimose, Egypt was “smote by God” (he says that he forgot the reason) thus allowing the Hyksos to conquer Egypt without a fight.

That sounds like the exodus.

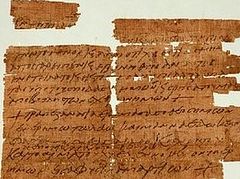

There’s more. The Ipuwer Papyrus has long been noted for its parallels to the Book of Exodus- but the connection has been dismissed, because the chronology doesn’t line up. On a revised chronology, however, it fits together. The Ipuwer Papyrus declares that “the river is blood” that “the children of the neck are slain” that “gold and lapis lazuli have been strung on female slaves” that “darkness is everywhere” and that the Hyksos from the east have invaded and conquered.

That sounds like the exodus.

And that is the pillar of chronological revisionism. Once the exodus is plugged in at this point, one can plug in the conquest forty years later. And what does one see at the end of the Early Bronze Age and the beginning of the Middle Bronze (a new chronology archaeological date for the exodus)? Well:

1. You have a very short layer of nomadic settlements in the Sinai wilderness.

2. You have five conquered cities in the region of Midian, apparently corresponding to what occurred in Numbers 31.

3. In the land of Canaan, the walls of Jericho have fallen outwards, and the city has been totally burned and left unsettled- except one small portion of the wall, as Rahab lived in the wall.

4. A dramatic, higher culture, very quickly conquers and replaces an older culture. This is the case in cities all over Canaan.

The relation of the Hyksos to the Amalekites provides another insight into biblical history. Why was it that Saul had to fight the Amalekites in 1 Samuel 15, centuries after the exodus? Revisionists have argued that this is because the Hyksos had just been expelled from Egypt. Hard revisionists like Courville put the expulsion in the life of Saul, while softer revisionists like Rohl date it a century or so earlier. The situation is thus: the Amalekites have been expelled from Egypt by Pharaoh Ahmose, and King Saul is sent to destroy them before they reenter Egypt. Elsewhere in Samuel, David encounters an Amalekite with an Egyptian slave.

This also explains why Egypt and Amalek reappear on the scene at the exact same time in biblical history, which otherwise appears a very curious coincidence. Egypt virtually never appeared throughout the period of the judges, because they were still ruined and ruled by a barbaric people. But within a few decades, Amalek is kicked out and Egypt revives, so that Pharaoh gives his daughter to Solomon.

Speaking of Solomon, taking Courville’s relative dates for Egypt and Israel, this explains why so many people have thought that Israelite proverbs borrowed from Egypt. Actually, when you fix up the chronology, the 18th dynasty (which displays enormous similarity to biblical material) was influenced by Solomon. Allusions to Solomonic proverbs are on the walls. David’s Psalms appear to influence some of their own poems. Love poems such as the Song of Solomon become popular.

There’s so much more I could say, but I want to give some pointers on where to go if you want to search this out further:

The difference between soft and hard revsionism lies in whether one is committed to the biblical chronology and the biblical history, or the biblical history alone. If the latter, one is not constrained by the biblical date for the Flood (2274 BC) which requires Egypt to have lasted about 1800 years rather than the mainstream 3000.

Soft Revisionists

Pharaohs and Kings by David Rohl. This is a brilliant and terrifically written book. I disagree with his analysis of the el-Amarna letters and his synchronisms with the period of Saul, but stand totally behind his archaeological analysis of Solomon’s time and his work on the exodus and conquest.

Centuries of Darkness by Peter James. This doesn’t look at ancient chronology from a biblical perspective, but points out the problems in the conventional chronology with respect to other civilizations. In order to key in ancient history to Egypt’s history, scholars have actually inserted a dark age of about 300 years all across the ancient world (except Egypt). The problem is that the culture before the dark age is identical to the culture afterwards- which makes no sense is this period of time existed.

Redating the Exodus and Conquest by John Bimson.

Hard Revisionists

The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications, Vols I and II by Donovan Courville. Courville was a pioneer. An Adventist scholar who saw that the chronology of the ancient world must be wrong if the Bible is true, he was one of the first to foray into this territory. He was mocked when he wrote the book, but now scholars such as James and Rohl are picking up on this (without giving him credit).

https://sydney.academia.edu/DamienMackey

That page contains a huge volume of articles by Damien Mackey, a scholar who did a PhD dissertation on a new chronology of ancient Israel. Unfortunately, his work was rejected (by one out of three of his examiners) for a PhD and he received a Masters. Much of Mackey’s work is terrific. However, he is very trigger-happy with parallelomania, and has a bizarre tendency to identify biblical kings as Pharaohs of Egypt, which I don’t think works in the least. Read carefully and critically, but read.

The only place in the ancient world where there were "Pharaohs" was the Arabian peninsula; specifically what is north Yemen today.

Ancient Egypt had colonies throughout the middle east, but the primitive tribes of the Arabian peninsula did not.