Should we read the Philokalia if we haven’t read the New Testament all the way through? Have we ever found ourselves playing a spiritual air guitar? What does it mean to progress in the spiritual life?

The present article is the introductory lecture to the series: “Prayer of the Heart in an age of technology and distraction” delivered by Fr. Maximos (Constas) in Feb. 2014 to the clergy of diocese of LA and the West of Antiochian of N. America at the invitation of His Eminence Metropolitan Joseph. The audio version of this lecture first appeared on Patristic Nectar Publications, and is published here by permission.

Fr. Maximos is the presidential research scholar at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of theology in Brookline, MA. He is an Athonite monk, one time professor at Harvard Divinity School, accomplished author and translator and lectures internationally in both academic and parochial venues.

* * *

I used to have a colleague who would say that he was very low-tech and it was only recently that he learned that his AM radio works in the afternoon. So whenever I find myself fumbling with microphones and PowerPoint and lights I think of that remark. Thank you, Your Eminence for the invitation to be here with you, and thanks to Fr. Mark. It’s a great honor. This is the first time I’ve been invited to speak outside of the GOA, so it’s good to be with you and I ask for your blessing and prayers that God may give me the strength to speak to the best of my ability and to speak reverently, and as St. Maximus the Confessor says, so that my words will honor the Word and not dishonor Him.

Before turning to my own remarks, I want to thank Your Eminence for that long citation from The Life of the Virgin. I was intrigued by the organic connections that the feast of the Presentation which we’re still celebrating and obviously of the Mother of God with the Crucifixion and Resurrection, largely through the prophecy of Symeon, who at this remarkable moment in the Temple says that this Child is a sign that will be spoken against and is set for the rising and falling of many in Israel, and turning to the Theotokos he says a sword shall pass through your own soul and from the early days of the Church this was taken as a foreshadowing of the pain that the Virgin would feel at the foot of the Cross. The pain that she didn’t feel in childbirth she felt at the foot of the Cross. It’s’ a wonderful moment that we’re in here with the feast of the Presentation looking ahead to the Crucifixion and from there of course to the Resurrection.

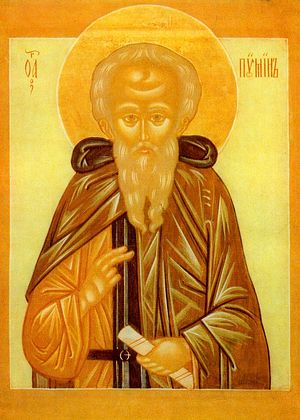

There’s also an obvious bridge to the things that I hope to share with you, inasmuch as the Theotokos is very much a type of every Christian soul. When I see the image of the Theotokos in the eastern apse of the church, either with the Child in her womb, which is what the medallion shape signifies, or holding the Child, I see an image of every Christian soul in whom Christ has been born, in whom Christ has taken His place. As far as I know the first ecclesiastical author to have said this is St. Gregory of Nyssa in On Virginity where he says what took place in the Virgin physically or materially must or will take place in every Christian soul spiritually. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the actualization of Christ in the womb of the Virgin and the actualization of Christ in the soul of the believer. There are actually icons of some saints, such as St. Menas, standing in the classic orans position with a medallion on his chest and the figure of Christ Emmanuel inside. It’s rare, but it is seen.

St. Symeon the New Theologian, who knew the writings of St. Gregory, says that indeed there is one Theotokos—one human being with that title in a very unique and unrepeatable way—but all Christians are called to go on to become theotoki. The first time I read that I found it very striking. St. Symeon is famous for making very striking remarks and using very vivid imagery and this is one example. It’s a very bold thing to say but it’s certainly very true and powerful.

I have the great honor and privilege to work with young men who are preparing for the priesthood. I consider this to be probably the most important thing I’m called on to do in my life because what I share with them and help to do will have impact with the people they work with. The life of a priest impacts hundreds and thousands of people, so I take this work very seriously. They are younger guys, so they’re still learning and sometimes they have incorrect ideas, so sometimes I have to make cognitive adjustments, sometimes scold, to try different approaches.

One of the common human shortcomings I see is that many of them are anxious to read a work like the Philokalia or other advanced writings, but yet they haven’t yet tread the whole of the New Testament. They want to have mystical experiences of God—they pray hard, they go to church, and their minds run away with them with their fantasies, and they want these most lofty mystical experiences before they’ve undertaken even the most basic kinds of ascetic practices. ”Do you fast on Wednesdays and Fridays?” “No, because they serve cheese in the cafeteria and I end up eating the cheese,” but they’d still like to have these mystical experiences. Cheese and mystical experiences aren’t necessarily incompatible but there is a proper and natural order to things.

It’s a human impulse to want the best and greatest when we see it, but we forget that there are other things we need to do before we’re ready to achieve that level. We think we’re ready for great achievements before we’ve even attended to little things which somehow seem beneath us. We can’t stoop to them because we’re theologians and we’re educated and we're seminarians and we’ve been called by God, so we can’t embarrass ourselves by publically doing little things—we have to be seen doing great big things. But this of course is to forget the words of the Lord Who says in the Gospel that he who is faithful in a little is faithful in much. The Greek text is interesting here because the word for in a little is in the singular. “He who is faithful in one little thing,” as it literally says, is faithful in much, and the Greek here is “many things.” This doesn’t always come through in the standard English translations and I take this to mean that the person who is faithful in one little thing will somehow acquire a skill set, or discipline, or ethos. Faithfulness in one little thing will somehow result in faithfulness across a broad spectrum.

Sometimes I think there are no great things; there are only little things and if we could attend to them then the great things would follow. The most obvious example is something like fasting, which is not exactly little, but it’s one thing. If a person could be faithful to the discipline of fasting, which seems simple in a way, and acquire that discipline, think of the power he would have in other areas—to withstand temptations, to not allow certain thoughts in his mind or react to certain impulses like anger or lust or pride or things like this. We can’t possibly begin to take up the struggle against these greater sins and temptations and all the rest if we haven’t been able to do that on a micro-level. I think if you do it on the micro level you’ll find that the big things don’t seem so big or powerful anymore, because you’re acquired strength of soul or stability or discipline of character which can be applied across a whole range of experiences or phenomenon.

You might want to play piano like Chopin or Beethoven, It’s a good desire to bring beauty into the world. Music is a gift from God. Read St. Basil’s first homily on the Psalter which has a very beautiful and fairly well-known passage on the theological basis of music, which he says is a gift to the Church from the Holy Spirit. To play like them you first have to spend a lot of time practicing scales. Just the wish or desire is not enough. You can’t just sit down and play like a virtuoso because you think you’d like to do that. It takes a lot of hard work. You hear people say today that there’s no such thing as innate genius—everything is quantified, and they say it takes 10,000 hours to acquire mastery or genius in a particular area. It’s no mystery—it’s simply hard work. Some people are obviously smarter than others but with 10,000 hours of work I believe just about anybody could become a master of just about anything.

But if we don’t exercise, don’t practice our scales, so to speak, in the physical and spiritual world, we’ll end up in the spiritual world playing the equivalent of air-guitar. It’s not easy to pick up a guitar. It hurts your fingers at first, you have to build up callouses and it takes times. So you think, “I don’t have time for that but I’ll get in front of the mirror and do some air guitar.” It’s a bit of a fantasy. Or we might think we’re wrestling with God, but actually we’re just shadow-boxing. We don’t want to be air-guitarists or shadow-boxers—we want to be spiritual artists, musicians and virtuosos—people who aren't simply emanating beautiful music but people whose lives are beautiful music because of the discipline and work that they’ve done. It’s important to do things in their proper and natural order. What is proper is what is natural. When you build a house you build the foundation before you put the roof on, but my students want to put the roof up there before having laid the foundation, and of course that’s an odd plan to have.

The sayings of the desert fathers are really remarkable—some of the oldest Christian literature we have and yet it sounds so contemporary, fresh, modern, and relevant, partly because the whole ethos is just stripped down to the essentials and simplicity of the desert. There is a story from Abba Poemen who is one of the more prominent desert fathers. Apparently a layman from a nearby city had heard about his reputation and wanted to meet the great desert father, so he packs his belongings, treks across the desert and goes into the mountains to find the place where Abba Poemen lived. He knocks on the door and Abba Poemen invites him in. They sit down, Abba Poemen offers him some sustenance, and immediately the man is eager to start talking about the Kingdom of Heaven, and the moment that Abba Poemen hears this, he recoils from the man, and basically turns his back to him. The man realizes that something has gone awry and doesn’t know what to do so he stands up, collects his things, and heads back down the mountain.

But as he’s trekking through the desert his thoughts begin to work within him: “I came all this way to see this man, I expected to be greeted by him and I wanted to talk about the Kingdom of Heaven, and what kind of treatment was that?!” and he starts to get angry, and he turns around and decides to go back and confront Abba Poemen. So he returns to Abba Poemen, demanding an explanation. And Abba Poemen looks him straight in the eye and says, “If you come here wanting to talk about the Kingdom of Heaven, I have nothing to say to you, but if you come here and you want to talk about the passions, well then sit down and open up your heart and I will fill it with every manner of good thing.”

The man wanted to talk about the Kingdom, but we need to talk about the passions first, because they are the very things that came into our existence when we lost the Kingdom of Heaven. How can we talk about the Kingdom without addressing the real state we find ourselves in? We want to talk about light but we’re filled with darkness. We want to proceed to the higher mathematics—reading the Philokalia and having mystical experiences—before we’ve read the New Testament or committed ourselves to a basic Christian discipline or before we’ve had the courage to face the darkness of the passions within us. The word “passions” is problematic because it doesn’t mean much in our language anymore—we have a passion for golf or politics—a better word is “addiction”—passionate attachments, whether to physical things or ideas and images like my own sense of self. Just like food, there is no limit to the things that people can get hooked on or the places that people can get stuck in their development. It’s a strong and hard word, but it’s a better word and consistent with the Fathers.

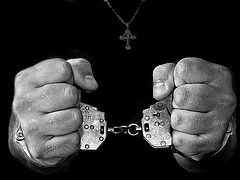

The spiritual root, in a sense, of all addictions is this impassioned condition that all of us have. Our focus here is about inner attention, not about being distracted or concentrating on things outside of ourselves, but about the inward turn to discover the grace of the Holy Spirit within us given at Baptism. When we withdraw our libidinal investment from the world and turn our attention inward again, in addition to the presence of God we will find within the core of our bodies and being the darker things within us, and maybe it’s their presence that prevents us from looking inward, because its messy, and it’s been festering so long, and we’re in denial, and we don’t want to deal with it. So the focus on the Philokalia is not just about the Jesus Prayer, although that’s central, but there are other things that come with it. And a big part of that is seeing and recognizing and struggling with the passions. I won’t say conquering the passions because we can’t do that. Elder Aimilianos, former abbot of Simenopetra, says when you’re tied up (which is what being in an impassioned addicted state is), you can’t untie yourself. Someone else has to come along and untie those chains and locks, and of course that is the grace of God. What belongs to us is first to discover the darkness within ourselves, and it’s a very hard thing to see.

Progress in the life of virtue is not about feeling better and better about yourself or thinking you’re becoming more virtuous, but the more someone progresses spiritually the more of their inner darkness God will allow them to see, because it’s very hard to see, and He won’t let you see it if He knows you can’t handle it. It’s a crushing, devastating thing to see, and it’s also humbling, and God gives His grace to the humble. That acknowledgment of our incapacity and weakness is what attracts the grace of God to us. There can be no authentic encounter with the holiness of God that doesn’t simultaneously result in a revelation of my own unholiness.

For me the great Biblical image of this is St. Peter in his encounter with the Lord when they’ve just finished fishing and caught little or nothing, and the Lord tells them to go and try again. Of course St. Peter knows his trade, he’s a fisherman, and here comes some carpenter to tell them what to do? Peter doesn’t say “Hey, wait a minute.” We tend to be very sensitive about our turf, and don’t like other people to tell us what to do. So Peter is a professional fisherman, but he goes and casts his nets again, and they are filled to the brim, and Peter realizes that whoever this Jesus is, He’s not an ordinary person. There’s something about Him. And what does he do? He turns to Jesus, and although we’re used to it from hearing the Gospel so often, he offers a really striking response. He falls on his knees before the Lord and he says, Depart from me O Lord for I am a sinful man. There it is. The revelation of the holiness of Jesus, of God, is authentic for Peter here because with it comes awareness of his own unholiness. It’s not putting Peter down, it’s not diminishing or belittling him. He’s not damaged psychologically. It’s a saving wound. It’s a compunctionate experience that allows him to know himself and at the same time reveals the fullness of the presence of Jesus to him.

St. Maximus the Confessor, in a play on words, says, “to discourse (“logos”) on the passions, is to descend into Hades with the Word ("Logos").” Someone may begin a logos on the Logos “not in order to remain there, but to break the bonds of the soul’s attachments to the world and so rise with the Word.” That’s very consistent with the teaching of Abba Poemen that we need to descend deeply into discourse on the passions, not to stay and take up home there, but to rise up from that depth and be resurrected and be revitalized with the word of God.