Source: A Lamp for Today

June 3, 2016

John 9:1-38; Acts 16:16-35; Psalm 2; Daniel 7

As we move towards Ascension Day, that high point of the great story when our Lord reveals his might and glory, takes our humanity up on high, and presents it to the Father, we hear, on this Sunday of the blind man, two stories of conflict between Jesus (and his followers) and the world. We have been set up for these stories by our midweek reading (Wednesday) of Acts 14:20-15:4, where Paul instructs new believers that “We must through many tribulations enter the kingdom of God.” As he well knew, these tribulations come in different forms, sometimes involving persecution from religious authorities, and sometimes from political powers. One of the most amazing collusions in history was the coming together of Pharisees and Sadducees (polarized Jewish sects) and of Jewish and Gentile leaders in order to crucify the King of Kings and High Priest of the cosmos. As Psalm 2 foreshadowed the dire situation, “The kings of the earth rise up, and the rulers take council together against the Lord and against his anointed.” This opposition from religious and political rulers (not always clearly differentiated in the ancient world, of course!) continued against the newly formed Church, for the disciples are not greater than the Master, and must follow his path. Before glory comes suffering—from the world, certainly, but also, more heart-breakingly, from those who should recognize the LORD of all. He came to HIS OWN, and many of these did not receive him—or his followers. As Jesus warned them, “They will put you out of the synagogues; indeed, the hour is coming when whoever kills you will think he is offering service to God” (John 16:2).

So it is with our readings for this Sunday. The marvel of the man born blind, told in John 9, goes unmarked by the religious authorities, who are already determined to thwart this upstart, Jesus. Indeed, two episodes earlier, they have sent men to arrest Jesus (chapter 7), who hear the Lord speak and come back mesmerized, to the scorn of the authorities. And in the chapter just before this one, Jesus has told them that they are not true sons of Abraham, but on the side of evil: for this they tried to stone him! Now, they fasten upon the timing of the miracle—the Sabbath. They have no idea, however, who they are up against! Listen to the tone of Psalm 2, and the inevitability of Jesus’ victory over these powers:

Why do the nations conspire, and the peoples plot in

vain?

The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take

counsel together, against the LORD and his anointed,

saying, “Let us burst their bonds asunder, and cast

their cords from us.”

He who sits in the heavens laughs; the LORD has them in

derision.

Then he will speak to them in his wrath, and terrify them

in his fury, saying,

“I have set my king on Zion, my holy

hill.”

I will tell of the decree of the LORD: He said to me,

“You are my son, today I have begotten you. Ask of

me, and I will make the nations your heritage, and the

ends of the earth your possession. You shall break them

with a rod of iron, and dash them in pieces like a

potter’s vessel.”

Now therefore, O kings, be wise; be warned, O rulers of

the earth.

Serve the LORD with fear, with trembling kiss his feet,

lest he be angry, and you perish in the way; for his wrath

is quickly kindled. Blessed are all who take refuge in

him.

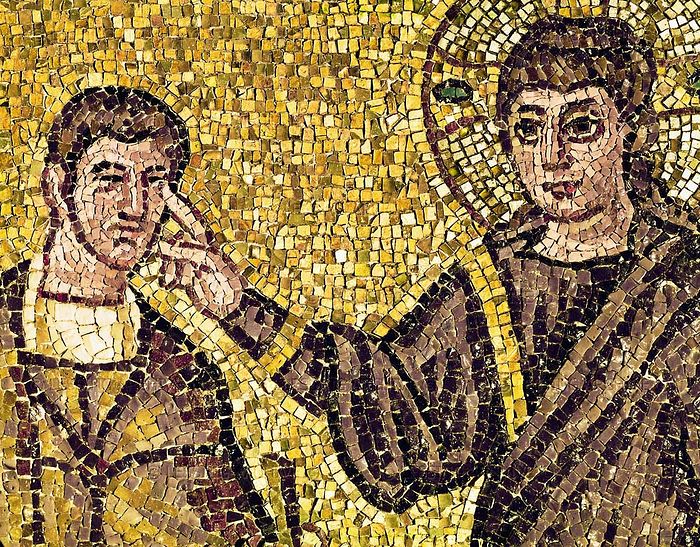

We who have read John’s gospel from the beginning are in a position to see the dramatic irony of the story. For we have already witnessed the Lord’s mastery, and with the disciples we know that “[a]s the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself, and has given him authority to execute judgment, because he is the Son of Man. (John 5:26-27 RSV).” The blind man, too, is going to learn this progressively, through his astonishing interactions with the Master. In a similar way to St. Photini at the well, and the paralytic, the blind man comes into contact with Jesus, and his understanding deepens gradually. First he obeys him as a “prophet,” going to Siloam to wash; then, when questioned by the authorities, he says that they should realize that he is “from God” because no one else could possibly bring sight to someone born blind; finally, Jesus comes, asking if he believes in “the Son of Man,” and when the blind man is confused, identifies himself to the man, who then worships.

We should remember, yet again, that the title “Son of Man,” though intimating Jesus’ solidarity with humanity, recalls the visionary sequence of Daniel 7, and its great climax. In those visions, the people of God have gone through a series of oppressive and cruel Gentile autocrats, experiencing great humiliation. But in the end comes one “like a Son of Man,” who ascends on high, and is given power, and glory, and kingship, and authority— his very own power born of his intimacy with the Ancient of Days, the Father, and glory which he shares with the saints, who will “shine like the stars” (Daniel 12:3).

But the religious leaders are not interested in God’s glory. Instead, as Jesus has criticized, they “receive glory from one another” but do not care about the true splendor, which comes, indeed, by way of suffering. If they had looked closely they would have seen, in Jesus’ acts, the very signature of God’s handiwork: Jesus works with MUD, and his own power (signified by spit, and not breath this time), as the Creator did at the dawn of the world. He remakes this man, as he had originally formed Adam, and waters his creation, as he had in the beginning. The direct touch of God transforms this blind man, who becomes a seeing being, just as Adam became a living soul. The man’s eyes are covered with the stuff of the earth, and he is sent to wash, and he sees! What happens physically to him is mirrored by his spiritual condition, which grows in stature from the beginning to the end. He knows only a very little—what Jesus has done, and how it has transformed him—but he holds on to the little that he has. Even his parents will not risk the truth, and they redirect the questioning rulers to ask their son, not them, because he is a grown up! His certainty over-rides the prejudice of that day, that those born with a deformity must be mired in sin—either that of their own, or that of their parents. With what certainly looked like impudence, he argues with the rulers that Jesus must indeed be a prophet. Jesus has healed, of course, on the Sabbath, when God ceased his work. But that work is not entirely finished in a fallen world, is it? And the man is the sad collateral damage of the fall, whose pain will now be turned around to the glory of God, who continues to care for his creation, and does not simply create, then abandon the work of his hands.

“You are born in sin, and you are teaching us?” retort the leaders. But the blind man has something to teach—once he was blind, but now he sees. Unlike his parents, who fear being expelled from the synagogue if they are suspected of supporting Jesus, the man clings to the truth. And he pays for it—they DO cast him out, which might seem like a very sad thing after, finally, his disability has been healed so that he could see the Torah scroll in the synagogue with his own eyes, and could even enter the Temple now. (The lame and blind, according to 2 sam 5:8, were not allowed in the Temple; certainly they, with other “disfigured” people, could not be priests, even if they were born of the house of Aaron, cf. Lev. 21:18.) Jesus called such to him (Matthew 21:14) and healed them in the Temple, making them kings and priests with him! But the religious authorities—at least many of them—were so intent on their own reading of Torah that they could not see how God was renewing his people and the world, when he visited us. The blind man may have lost his ability to meet with others around the Torah in the synagogue, or enter the Temple, for the very first time: but in front of him, seeking him out, healing him physically and spiritually, was the One who WAS the true Temple, and who would transform all who believed in him into that very growing Temple of God of which we, too are a part. And he worshipped him, counting those other things as so much dross! For the blind man, when Jesus and the world were in conflict—even Jesus and the religious authorities—there was NO contest. The Son of Man shone incomparably more brightly.

Paul and Silas find themselves in a similar fix in our epistle reading for Sunday, (Act 16:16-35.) Going on their way, they encounter a young slave girl who follows them with annoying chanting, and they heal her of demon possession. The problem is, her very infirmity had brought economic prosperity to her owners, who used her as side-show entertainment to tell fortunes. These economically driven men are not amused:

As we were going to the place of prayer, we were met by a slave girl who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners much gain by soothsaying. Paul… turned and said to the spirit, “I charge you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her.” And it came out that very hour. But when her owners saw that their hope of gain was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the market place before the rulers; and when they had brought them to the magistrates they said, “These men are Jews and they are disturbing our city. They advocate customs which it is not lawful for us Romans to accept or practice.” The crowd joined in attacking them; and the magistrates tore the garments off them and gave orders to beat them with rods. And when they had inflicted many blows upon them, they threw them into prison, charging the jailer to keep them safely.

We all know how the story progresses, and the glory with which it ends. As they sing in the bowels of the prison, just as the three sang in the firey furnace, they are released by an act of God—an earthquake, and have the opportunity to witness to the jailer, who would have committed suicide because he supposed his prisoners had escaped. Paul prevents this, and on hearing the gospel, the man and his whole family are speedily baptized!

The story turns from drama and danger to great joy:

“Men [he asks them], what must I do to be

saved?”

And they said, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you

will be saved, you and your household.”

And they spoke the word of the Lord to him and to all that

were in his house.

And he took them the same hour of the night, and washed

their wounds, and he was baptized at once, with all his

family. Then he brought them up into his house, and set

food before them; and he rejoiced with all his household

that he had believed in God.

So, then, Paul and Silas turn around a story of persecution and the calamity of the jail-keeper, to a story of great joy. Economic giants and pagan political leaders seemed to have the upper hand, but God has delivered and saved, showing his power through the earthquake, and his compassion through the speedy words and actions of Paul. As with the blind man, God uses both miracle and natural elements, for the jailer and his family are immersed in water, believe and are saved. This is not, however, the end of the story! If we read a little beyond our appointed passage, we discover that Paul and Silas are not above getting involved in political matters as they serve the Lord. Listen to how the story continues, as the authorities realize that the warning has been given, and that Paul and Silas are not deserving of a prison sentence:

But when it was day, the magistrates sent the police, saying, “Let those men go.” And the jailer reported the words to Paul, saying, “The magistrates have sent to let you go; now therefore come out and go in peace.” But Paul said to them, “They have beaten us publicly, uncondemned, men who are Roman citizens, and have thrown us into prison; and do they now cast us out secretly? No! let them come themselves and take us out.” The police reported these words to the magistrates, and they were afraid when they heard that they were Roman citizens; so they came and apologized to them. And they took them out and asked them to leave the city (Acts 16:36-39).

I find this very interesting. The apostles have been honored to suffer for Christ: but they also want to set the record straight in the social sphere. They know full well that to be a Christian involves also being persecuted—just as Paul has taught in a previous chapter. Only by way of patience in trial does true glory come. Though they are not “of the world” they are nonetheless in it. And, it seems, this means that they consider it appropriate to appeal to every power and gift that they possess—even Roman citizenship! Injustice has occurred here, and it must be recognized. It will, of course, be many years before Christianity receives public approval from the political authorities—and with that approval, sadly, also came a softening of the Christian community, which was no longer kept on its toes by threatened persecution. Nonetheless, St. Paul appealed to his status in insisting upon justice, so far as it existed, in his day. And we, too, pray routinely for the powers-that-be, so that there is peace, and so that we continue to have a social space in which to worship and to witness freely. Our morning prayer mirrors the pastoral letters of the NT, which call on us to pray in this way: “Save, O Lord, and have mercy upon all world rulers, on our president and on all our civil authorities. Speak peace and blessing in their hearts for Your Holy Church and for all Your people, in order that we may live a calm and peaceful life, in all godliness and dignity.”

Such prayer, it seems, may be coupled with an insistence that the authorities live according to their own laws, just as St. Paul required of them. Someone might have, in the apostle’s day, considered his requirement that the magistrates acknowledge their wrong-doing to be a petty clinging to rights—why did he not simply leave “in peace”? Clearly St. Paul believed that something important was at stake. His social standing was not to be obliterated, so far as he could manage it, by his allegiance to Christ. One could be a good citizen and ALSO a Christian, except where these two worlds collided. In his letters, we see the implications of this conviction, and we see it also in the early paragraphs of Luke’s writings, where he commends Christians to the ruler “Theophilus,” showing them that Christianity is BENEFICIAL to society in general, and not pernicious. In the days of the early Church, Christians were considered with even more suspicion than Jews, who had been around for a long time, because they would not engage in the civil religion of their day, honoring various gods and goddesses for various events, and even showing respect to the emperor as a divinity. As a result, they were called “atheists” (those who were AGAINST the gods), though they worshipped the true God. Jews were given a grudging pass against reprisal for this religious standoffishness, because they had a long history. But as Christianity came to be distinct from the rest of the Jewish family, beginning about 2/3 way through the first century, it came out from under that protective umbrella, and faced, as we know, great distress. Lies were told about this new group, including charges of infanticide at their Eucharists, and many other supposed insidious actions. We are grateful that things eventually developed so that Christianity became a licit religion, though of course such acceptance brought new challenges.

Today, we appear, of course, to be on the downturn, in terms of legal acceptance. The pressures take different shapes: instead of actual religion, it is ideology that marks us as different. Those who remain true to the gospel of conversion and transformation will find themselves marked, both in informal ways, and also, sometimes, in legal status, for this fidelity. Our adherence to one God stands in marked contrast to the post-modern attitude that all stories matter, and that there is no one metanarrative that claims our attention. Subtle and not-so-subtle pressure comes against Christians, who will, only because of such convictions, and not (we hope!) because of attitudes towards others, be considered arrogant in holding to Jesus alone as the Way, the Truth and the Life. Orthodox may be under particular scrutiny because of their teaching concerning the visible, apostolic Church, and our hedge around the Eucharistic table: to many this seems uncharitable in the extreme. Our only defense under such criticism is to exhibit great love and concern for others, just as St. Paul did in the jail, when he might simply have walked out free. Our words and actions, and life together, need to show both the decisive power of God and his unspeakable compassion for others. Some of us may find ourselves in difficult legal situations, even though we do not seek this out. At such times, it will be a judgment call whether we should be like the holy Lamb of God, who did not open his mouth, or like St. Paul, who called on the leaders for a public exoneration. In the OT the Son of Man is a figure who is given great authority and the power to judge; Jesus reminded us, too, that the Son of Man came not to serve himself, but to suffer and die; in Himself, then, our Lord combines both Justice and Mercy, and this combination should also mark our own identity. How to play this out in the world becomes more complex when it is not unbelievers who launch the challenge, but religious authorities who have a different view of the gospel than we do! It will be in prayer and council with our spiritual advisors that we determine whether we should treat such matters as an internal Church dispute, not for the eyes of a scorning public (who will delight, no doubt, to see Christians, whom they do not differentiate as Orthodox or otherwise, in legal action against each other) or as a matter of political and social justice that must be fought for the sake of Christians and society at large. We are not yet at a point in our society that all of us will face such challenges—but some will, and we should pray for their wisdom and safety. In all these matters, it is not simply the well-being of Christians that should be our concern, but the health of society in general. We should be concerned, I would argue, not only for our religious liberty—though this is a precious thing that we would not seek to lose!—but also for the evident slide of those around us into self-destructive hedonism, monstrous disregard for the lives of the unborn, disabled, suicidal, and elderly, sexual confusion, and untenable relativism in many other areas of ethics and life.

Not all of us have the same calling. We must be both wise as serpents and innocent as doves. All are called to pray; some are called to suffer and show meekness; some are called to give relief to those who are in distress because of society’s current blindnesses; others are called, in knowledge of the system’s ways and laws, to champion the liberties that we have, and so give encouragement to others.

Jesus brought light to the blind man, and we bear the light of the world. St. Paul showed himself salty: and we are to be the salt of the world, helping to preserve it so that folks continue to have an opportunity to hear the gospel. We are sometimes, perhaps increasingly, at odds with the Powers-that-Be. May the Holy Spirit show us how to make the most of this situation, and not simply to act out of fear, or anger, or self-justification! For in the end, those whom we might be tempted to consider enemies, and who dismiss us or are suspicious of us, may become like the blind man, seeing and worshipping, or like the jailer, no longer intent on taking his life, but rejoicing in the truth!