The following article published on Orthodoxy and Modernity about Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) of blessed memory, who reposed on the eve of the Apodosis of the Meeting of the Lord, February 21, 2017, was written seven years ago for his ninetieth birthday, when the elder was still alive but paralyzed after a stroke. The medical incident that confined him to his bed occurred in around 2004, after a long life of service to God and people. Fr. Kirill continued to serve through prayers for people known and unknown to him, as one of the righteous pillars upholding the world, perhaps for the sake of whom God does not allow its utter destruction.

* * *

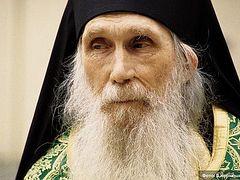

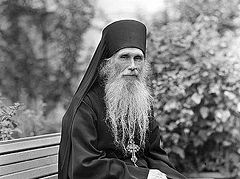

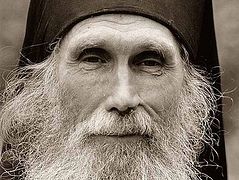

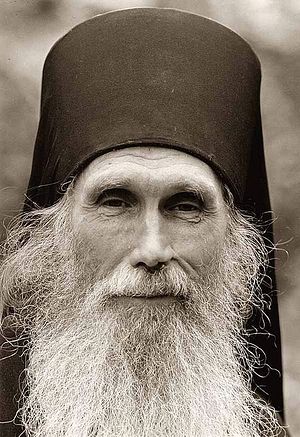

Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) The question as to whether or not there are elders today, and if so, how can we find them, is something that every priest hears from time to time. Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov), the long-time father confessor of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, would usually answer the question like this: “I don’t know about elders, but there are old men”—although he was and is one of the few whom we could call an “elder”, not only because of his age but according to the full meaning of this word as accepted by Orthodox Church tradition. An enormous wealth of spiritual experience, unfeigned humility and love, true dispassion transforming itself into that freedom from the passions that is the very goal of Christian asceticism and progress in the virtues—those qualities were seen over many years in Fr. Kirill by his spiritual children as well as people whom the Lord at least once in life led to his cell to resolve complex problems, to receive prayerful help, or simply for the consolation that is so scarce these days to people living in a cold, cruel world.

Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) The question as to whether or not there are elders today, and if so, how can we find them, is something that every priest hears from time to time. Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov), the long-time father confessor of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, would usually answer the question like this: “I don’t know about elders, but there are old men”—although he was and is one of the few whom we could call an “elder”, not only because of his age but according to the full meaning of this word as accepted by Orthodox Church tradition. An enormous wealth of spiritual experience, unfeigned humility and love, true dispassion transforming itself into that freedom from the passions that is the very goal of Christian asceticism and progress in the virtues—those qualities were seen over many years in Fr. Kirill by his spiritual children as well as people whom the Lord at least once in life led to his cell to resolve complex problems, to receive prayerful help, or simply for the consolation that is so scarce these days to people living in a cold, cruel world.

Probably a few years ago there was no need to talk about Fr. Kirill in order to clarify what place he occupies in the very recent history of Russian Orthodoxy. To his cell in the Patriarchal residence in Peredelkino people came to confess from all over Russia, from the countries that are now called the “near abroad”, and from countries that were are still are called the “far abroad”. Monastics and clergy, former and current brothers from the Lavra, laypeople and bishops, and finally, the reposed Patriarch Alexiy came to the father-confessor of all Russia in order to confess, make peace with God, and hear words of salvation. I think that everyone who knew Fr. Kirill at that time would agree that in him came true with amazing fullness and power the words of St. Niphont of Constantinople when he answered his disciple’s question about what true spiritual ascetic laborers would be like in the last times: not working obvious miracles, but wisely hiding themselves amidst people and walking the path of activity imbued with humility.

But it so pleased the Lord to try the precious gold of his righteousness by the final and most difficult, enduring temptation: in 2004 Archimandrite Kirill suffered a stroke, which at first completely immobilized him, and then practically deprived him of contact with the outside world. Practically, but not entirely. Bedridden, manfully enduring his illness, he did not seek support or consolation, but in brief moments, when his strength would return, he himself would support and console, exhort people to pray and not despond, and also to take care of their health…

We have published this modest offering for Fr. Kirill’s ninetieth anniversary—an article by his cell attendant, nun Natalia (Aksamentova), who for the past fifteen years has been continually with him, day after day gratefully absorbing that gentle light about which she speaks in her narrative on Fr. Kirill. Her text cannot be categorized in the genre of memoirs—she wrote it while Batiushka was still with us and his time had not yet come. It is more of a testimony to that miracle which is his life, about that strength, which, in Christ’s words, manifests in the extreme infirmity of a body worn out and refined by suffering. This testimony is so necessary and important for us.

The Gentle Light of Authenticity

It so happened that the stroke happened right before my eyes—sudden, quick, and with an appalling unceremoniousness. Just two or three minutes before, I had burst into the hospital room, amiably, noisily, with a backpack, a bag, thermoses… Batiushka adjusted his glasses, joked about my mountaineer’s appearance, took out the Gospels from the bed stand, and seated himself on the edge of the bed. I eviscerated my backpack, setting out the thermoses with hot food as I rattled on about some funny happening in our Peredelkino life, when suddenly he began to lean towards the pillow. With his right hand he removed his glasses and managed to place them on the bed stand before falling whole body onto the bed, landing on the left side. While the nurses were running to get the doctor I remained in the room with him one-on-one. I cried helplessly and tapped batushka on his sleeve. It seemed he was unconscious… But he never left anyone without attention in their troubles, and even then he opened his eyes again, slightly raised his head, turned toward me and quietly but calmly and firmly pronounced, “Don’t be afraid of anything… Glory to God for everything…” And his head again fell lifelessly back onto the pillow. This is how the line was drawn between two completely different lives—before and after the stroke.

* * *

Judging from that calm courage with which these last words were pronounced, this event had not caught him unprepared. It caught me and all of us unprepared—those who surrounded him and took care of him during the first eight months after the stroke, and those who did not have the possibility to serve him in a practical way but who were with us and him in their thoughts and prayers, sitting by his metal bed with moveable side railing… We were all sorrowing and grieving, condemned as we were—without him—to orphanhood, extraneousness, rootlessness, and loneliness. Fr. Kirill had that amazing human quality—next to him no one felt unneeded, forgotten, or hopelessly uncorrectable. The stroke did not intend to relinquish its position. Sudden and without warning, crashing down like a thunderclap, it was a disaster that went on as a very difficult and very long labor of asceticism. It was the labor of trust and astounding dedication to God. And this labor, as we are convinced after these years, is God’s great care for all of us and his unfathomable mercy.

* * *

No one thought that we would make it through all these years of pulling through and enduring to this date. It’s not easy to reach such an age even without a stroke, but with a stroke… Fr. Kirill’s strength is leaving him, of course. But—and I am not afraid of the paradox—such weakness and powerlessness can only be borne by an extremely strong person. When a weak person feels bad, the whole world usually has to hear about how bad he feels. But batiushka even now does not try to transfer his own cross to someone else’s shoulders. We never once heard the words “feeling bad” from him. There were times when we even scolded him for never asking anything from us, never complaining, or just as a human being showing the weakness forgivable for one in his situation. “How can I… After all, you are not made of iron,” he would answer. The custom of a respectful and considerate relationship to people, to their labors, the habit of never burdening them with himself in any way, always seemed like something that “goes without saying,” but during his years of illness it all suddenly flashed before us like a diamond.

* * *

<…>

I remember batiushka’s own words of two years ago, when he still had the strength and desire to say at least something: “After all, a person needs nothing besides God’s mercy!” We who are still young, healthy and strong need quite a lot—a good grade on our exams, our bosses’ good graces, a well-spent vacation, a pretty fall coat… But he who is deprived of absolutely everything, all attributes of a normal, quality human life, needs nothing but mercy. He never asks for anything—neither his former health, so that he could walk on a warm summer’s evening in the garden and feed the birds; nor some modicum of vision so that he could see and recognize those who come to see him; nor the ability to serve together with his dear brothers in his beloved Lavra; nor the ability to turn from one side to the other… Considering himself a sinner, he does not want to ask God for anything other than what He has already sent down. Because what was sent down was not impoverishment at all, but a new gift and new service. Because The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord from henceforth and forever more.

* * *

The only right that Fr. Kirill left himself was the right to defend his own ordinariness and insignificance… I do not think that anyone can recall even one revelation from him of supernatural help, or heavenly signs, or miraculous appearances—all those out of the ordinary things that could put batiushka in an exclusive place among people. How upset he was when in the early 90s, it seems, in Komsomolskaya Pravda an article appeared describing his almost fabulous clairvoyance! His exasperation knew no bounds. The article really was primitive, flat, and vulgar, but it did its work—Peredelkino was thronged by a crowd of gapers wishing to see into the future. Only when he was paralyzed would he as if accidentally pull back the sacred veil from the mystical side of his life, but he would then immediately rush to hide it again… “You’re praying, aren’t you batiushka?” we would ask, seeing his unusual state, and expecting to hear, perhaps, something. “Well, no, I was just… Just remembering…” and he would act as if he were nodding off. Nevertheless, his monastic vigilance could not be completely hidden from us who sat by his bed night and day. Either he would pronounce the prayer of absolution, or recount people’s names, or try (when he still could) to quietly sing something from the All-Night Vigil or Liturgy. All fifty years of his monasticism were spent with people, and with people, with remembrance of their sorrows and cares he continues to abide to this day.

* * *

As far as I can judge, he never considered himself an elder. But neither did he consider that he had the right to refuse anyone who came. This caused great problems—how could it be arranged that people could have the opportunity to visit him in his Peredelkino cell and at the same time make sure that he had at least some time to rest? “What can I do?” he would say in those days, “other than just hear a person out?” And he did hear them out… There were times when this would last from noon to two in the morning… At lunchtime I would run, forgetting to take off my apron, and call him to trapeza, to us in the next building. Even if he had no desire for food he would always come on time. Moreover he considered it his bound duty to participate in the dishwashing afterwards. Without the slightest shadow of morose seriousness, without any sanctimonious edification, but happily, good-naturedly, as if it went without saying he would rinse through the mountain of our dirty dishes and cups (the sisters and I managed to hide the other mountain before he could get to it), and then go and receive more people. And thus, every day. In the end this all began to seem like business as usual to us, too. Well, batiushka’s washing the dishes—what so strange about that?

* * *

Not having known batiushka as others did (at forty, fifty, or sixty years old), I was vouchsafed to see only this enlightened old age, radiating joy and peace, incapable of anger or even the slightest irritation over someone else’s ridiculousness… All of this seemed to come to him easily, airily, organically to his own nature. But judging from his own stories, his monastic path was a path of tough, continual, and deepened self-control. It all demanded, albeit unseen but colossal labor. No quarter with anything that contradicted the Gospel commandments did he ever allow himself. It is another matter that his rigor towards himself never led to ascetic severity with regards to those around him. He truly had a very kind and merciful heart. No one could ever accuse him of callousness or reticence, or of the behavior that inexperienced ascetics usually justify by their “exclusive” ascetic labors and aloofness towards earthly vanity. I dare to think that what took first place in this personal asceticism was not the number of prostrations and prayer knots, but the commandment about love. To never offend anyone, to preserve peace in his heart—that was batushka’s main concern, his key worry at every hour. And after all, how many of those who came to him were simply psychologically ill, whom it is a priori impossible to please. But Fr. Kirill submissively listened to the millions of criticisms aimed at him, demands to listen again and again, to receive confessions…

* * *

Often one had the impression that there was no ascetic labor (podvig) at all. That was how simply and accessibly he behaved himself. There was never a single incident when he would refuse someone, excusing himself with the need to read the monastic rule. One could suppose that he simply didn’t do it. But in fact he read his rule after midnight. When I would help him read it, it would become significantly shorter. That was because I would get tired, and he was very attentive to others’ exhaustion and would not permit himself to place a “burden hard to bear” on us. But he loved the prescribed cell rule of the Lavra like a source of enlivening dew. By reading it for him I didn’t so much help him as deprive him of his precious moments of consolation. But in his presence one never thought about that; one only believed that everything was going along beautifully. And that what will be, will be only good, bright, kind, and endless… like the love in his radiant eyes.

* * *

With him you always had the right to make a mistake. More than that—you had the right to your own opinion. Disagreement did not cause Fr. Kirill any perplexity or distress (at least he never displayed any distress). He would listen with interest and respect to another point of view and, if he became convinced of its validity, might change his own. Fr. Kirill never domineered over anyone and never forced on anyone his way of thinking about life. After listening to a request, unhurriedly asking about the details of the matter, he would tactfully offer his option for resolving the problem, and the rest was our right to choose. Life itself would reveal the consequences and that his advice was the only sure advice. I never cease to be amazed at how blithely some spiritual advisors might separate a married couple, send to a monastery someone who is still wavering in his decision, or in some way completely and crudely change a human fate. Fr. Kirill treated people with the utmost care, weighed every word, so that he would never wound another’s self-love or injure an infirm soul. But as for mistakes he not only did not coarsely point them out, but in general gave the appearance that nothing had happened. He gave people the opportunity to figure out their errors by themselves. It is not by chance that his favorite fragment of the “Patericon” was the story of Pimen the Great, who did not reproach the brother who fell asleep on the cliros during the services, but let him rest in peace. His ability to prefer learning over teaching, obedience over directing amazed us to the depths of our souls. It is another matter that we ourselves should have guessed that it would be better for us to be silent in his presence rather than share our opinions with him. We would have received incomparably greater benefit.

* * *

From the category of his usual virtues and his monastic self-discipline. I recall one incident when he entirely had the right to independently make a decision in one or another situation, but he called the Lavra in order to ask the father superior’s blessing. One day, when the father superior was absent, Fr. Kirill went to the Peredelkino church to ask permission of the rector there. When the rector turned out to be absent, and he could not receive either a positive or negative answer, Fr. Kirill decided to turn down the proposed event; and this regardless of the respect with which the Lavra superior regarded Fr. Kirill. During the first eight months after the stroke, when his life was literally hanging by a thread, conversations about death, about its possibly imminent visitation became an inescapable part of our hospital life. There was a moment when we had to ask the still living batiushka where he wished to be buried. Isn’t it strange to ask such things of an obedient monk? And he let us know that this really is a strange question. “I have superiors to make that decision,” batiushka answered.

* * *

In 2009 came not only Fr. Kirill’s ninetieth birthday but also the fifty-fifth year since his tonsure into monasticism and ordination into the deaconate and then the priesthood. These are serious numbers. We also have to consider that to his generations’ lot fell too many heavy trials. A man with his biography, who lived to such years, can only inspire amazement. There was collectivization, his friends and family were made to suffer, his half-starved youth in an atmosphere of totalitarian denunciations and arrests everywhere, World War II, and the unprecedented hardships of the postwar years. And that is not to mention what it was like to study in theological schools and save yourself in monasteries under an atheistic government. Sometimes I think, what must prevail in the character of a man who went through such trials and yet preserved not only his humanity but also his childlike love of life? Strong will, and firmness of character? Yes, they were there, without a doubt. Faith and resolve? They too were there. But just the same there is nothing firmer or stronger than a soft heart, filled with compassion for the whole world. He did not consider himself to be a benefactor of mankind; to the contrary, he was happy with his possibility to do good. He felt that he had received the benefaction. About three years ago, already bedridden, he said, “I thank God that I have been able to serve people…

* * *

I now remember the years of his confessions in Peredelkino. Our corridors were literally stacked to the ceiling with boxes of candy, packages of books, and little icons—giving visitors gifts was mandatory. Batiushka was overwhelmed with joy when there was something to give a person. And chocolates—they were scattered everywhere. Beyond those who came directly to him, the street sweepers, gardeners, plumbers, guards, policemen, electricians, residence employees—everyone was not only given chocolates but asked about their health, and daily affairs… That joyous enthusiasm with which batiushka would hand you a treat would always be transmitted to your heart. And Fr. Kirill never remained in solitude even during his brief evening strolls; someone would without fail “join him” for a talk. “How is batiushka?” the policemen, street sweepers and plumbers would ask me with tears in their eyes when I would return briefly to Peredelkino from the hospital. Even now the unanswered letters are grieving. Now we simply write down the names of the senders and give them to the altar for commemoration, but before, batiushka would labor scrupulously over each one of those letters. Over the course of a month he would have to answer two hundred or more letters, and if he wasn’t able to fulfill this “monthly norm”, the quantities would naturally rise. But today I myself like never before feel that acute need of his sensitive and watchful attention to my soul. And I feel very sorry for others. They might not receive even from their closest family even a fraction of the warmth and attention that batiushka imparted in his letters. What is notable: The ones whom he gave the most love and support were the sinners, those who were poor in spirit, which he considered himself to be. Fr. Kirill was simply happy to meet such souls.

I now remember the years of his confessions in Peredelkino. Our corridors were literally stacked to the ceiling with boxes of candy, packages of books, and little icons—giving visitors gifts was mandatory. Batiushka was overwhelmed with joy when there was something to give a person. And chocolates—they were scattered everywhere. Beyond those who came directly to him, the street sweepers, gardeners, plumbers, guards, policemen, electricians, residence employees—everyone was not only given chocolates but asked about their health, and daily affairs… That joyous enthusiasm with which batiushka would hand you a treat would always be transmitted to your heart. And Fr. Kirill never remained in solitude even during his brief evening strolls; someone would without fail “join him” for a talk. “How is batiushka?” the policemen, street sweepers and plumbers would ask me with tears in their eyes when I would return briefly to Peredelkino from the hospital. Even now the unanswered letters are grieving. Now we simply write down the names of the senders and give them to the altar for commemoration, but before, batiushka would labor scrupulously over each one of those letters. Over the course of a month he would have to answer two hundred or more letters, and if he wasn’t able to fulfill this “monthly norm”, the quantities would naturally rise. But today I myself like never before feel that acute need of his sensitive and watchful attention to my soul. And I feel very sorry for others. They might not receive even from their closest family even a fraction of the warmth and attention that batiushka imparted in his letters. What is notable: The ones whom he gave the most love and support were the sinners, those who were poor in spirit, which he considered himself to be. Fr. Kirill was simply happy to meet such souls.

* * *

But just the same, he is with us. And we are in his kind heart. Many, I know, are warmed by only the thought that there is a cell in Peredelkino, that there is that metal bed specially fitted for the bedridden, that there are those special mattresses that provide relative comfort… He exists and prays, remembering us, our dear, kind Fr. Kirill. When in that first horrible year after the stroke he was dying as he had a number of times before and there was talk of a tracheostomy, we were offered to take him to Germany, to better, as it was accepted to believe, doctors and medicine. His Holiness the Patriarch was ready to help. At his request the father superior of the Lavra came to the hospital in order to raise the question of Germany. Only this time did Fr. Kirill not obey. Barely alive, exhausted by pneumonia and torturous bronchial spasms, he quietly pronounced: “I’m not going anywhere.” The doctors in Russia saved us then, and saved us many other times with God’s help during those years. If we were to count the names of all the medical workers who took part in batiushka’s treatment we would have a serious list. From scholars and department heads to simple nurses and lab technicians. We bow down to all of them, for they helped him live so long.

Others who knew him will be gathering information on Fr. Kirill’s life, but for now we are simply preserving in our hearts the feeling of gratitude for that gentle, meek light of Christian authenticity, who radiated on us life, ascetic labor, and even the very countenance of this man. The Christian accepts human loss not entirely as loss, and there is no place in his soul for animal fear or panic. It is terrible to loose the thread of the spiritual connection that unites us with those whom we love and who laid down their lives for our souls. But it is up to us whether we loose it or not.

* * *

You ride in the tram or the subway. People everywhere, the usual Moscow crowds, fuss… But in your backpack there is a little book, the favorite book of your spiritual father, with which he never parted and knew almost by heart. It’s called the New Testament. You open it to any page… We then that are strong ought to bear the infirmities of the weak and not to please ourselves… And you see before you the face of this man, in whose soul your every grief drowned as in the sea. And you understand that nothing can ever completely cease as long as there is such a Word among those who dwell on earth. Glory to God for all things… How could it be otherwise?