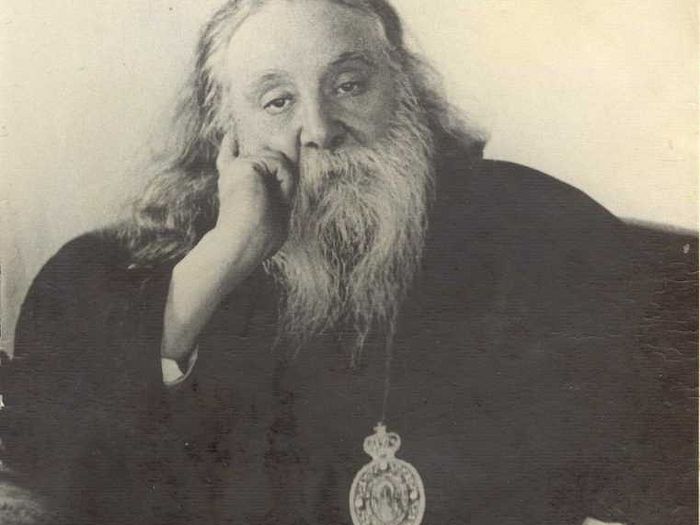

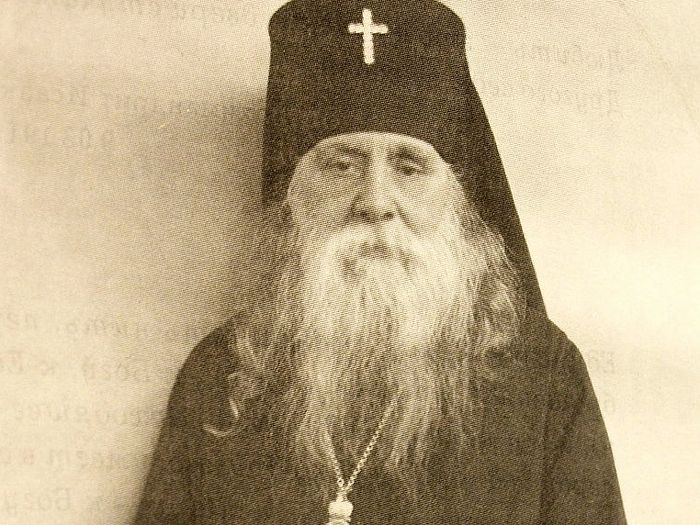

For many he was more well known as Sergius of Prague. Vladyka Sergius (Korelev), Archbishop of Kazan and Chistopol, spiritually cared for the Russian emigrants in Czechoslovakia during difficult times for Russia. He spent twenty-four years of his life in Prague, and served as hierarch in countries of Western and Eastern Europe. The archbishop’s ascetic labors also have great significance for us today.

Spiritual mission in emigration

On January 18, 1881, a son was born to the large merchant family of the Korolevs, who lived on Bolshaya Presnya Street in Moscow. He was named Arcady. This child was destined to become Archbishop Sergei “of Prague”, Kazan and Chistopol. But in those days, soon after the boy’s birth, this large family was left without its provider—their father died. The future archbishop’s childhood was spent in Moscow, and later the Korolev family moved to an estate near Moscow, in the village of Obolyanovo.

Because of the family’s poverty the youth could not enter a commercial school, and so after elementary school he continued his studies at the Dimitrov theological school. This was contrary to the traditions of the merchant class to which Arcady belonged, but it resonated with his spiritual yearnings, because he was very religious from his childhood. In 1896, the youth continued his studies in the Bethany seminary, and after that, in the Moscow Theological Academy. During that time but two grades higher, the future Patriarch Alexiy I (Simansky) was also studying in the Academy. The two youths knew each other and were friends.

At the time, the young Arcady Korolev had no thoughts of the priesthood; he intended to become a teacher in some religious institute. Nevertheless, after graduation from the Academy in 1906, he found himself in the Jableczna Monastery in Kholmishchi, which was on the border with Poland, where his friend from the Academy—Fr. Seraphim (Ostroumov)—was the abbot. The future archbishop was of a gregarious and energetic temperament, and never even thought about monasticism. However, the missionary and enlightenment function of the Jableczna Monastery, along with his acquaintance with Bishop Evlogy (Georgievsky) of Kholm, who had become his spiritual father from the outset, decided everything. In the very next year of 1907, Bishop Evlogy himself tonsured Arcady a monk, giving him the name Sergius, and a year later ordained him a hieromonk.

By 1914, Fr. Sergei had become an archimandrite and the abbot of Jableczna Monastery. But in 1916, this monastery along with its brethren was evacuated due to the German invasion. Archimandrite Sergei was able to return to Jableczna only three years later. He then began right away to restore the destroyed and wasted monastery. However this time of peace did not last long; in 1920 there was another war, this time with Poland.1 Then Archimandrite Sergei was appointed bishop of Belsk and vicar of the Kholm diocese. His episcopal consecration took place on April 17, 1921. But the Polish authorities did not want to accept his appointment, and thus Bishop Sergius was not destined to fulfill his duty. Anyone who did not support the creation of a Polish autocephaly was arrested and sent into exile.2

Thus, in 1922, Bishop Sergei arrived in Prague, the capital of what was then Czechoslovakia, where he lived the longest portion of his life in service to God—twenty-four whole years. He arrived in Prague penniless, knew no one there, but soon became acquainted with the Russian émigré community and learned to his joy that all of the parishes of the Moscow Patriarchate where being temporarily governed by his spiritual father, Bishop Evlogy. The latter immediately appointed Sergius Bishop of Prague, as well as his vicar representative in the parishes of Czechoslovakia and neighboring Hungary and Austria.

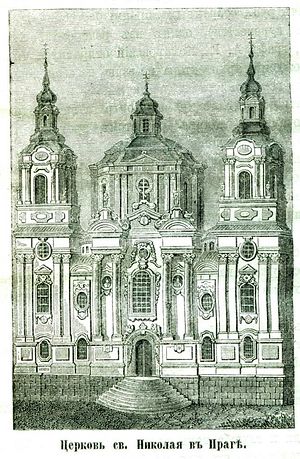

The only church in Prague that belonged to the Moscow Patriarchate was the St. Nicholas Church. Soon through Bishop Sergius’s efforts a beautiful church was built, dedicated to the Dormition of the Mother of God, in Olšany. The Russian émigré community quickly began to unite around Bishop Sergei, especially the intelligentsia—they found spiritual consolation with him, which in some part replaced the exiles’ homeland. Bishop Sergius’s role as a unifier was truly great. In those complex times, when various political views were causing divisions among people, including representatives of the Russian emigration in Prague, he was able to bring people together in one faith and make peace between them. Bishop Sergius never supported anyone’s political position, never took anyone’s side. Many all their lives remembered and carried the light they received during the Thursday meetings with Bishop Sergius over tea with “Brother Samovarius” as they called it. At these talks, people’s souls opened up, enemies were reconciled, and only familial feelings of love remained. Many spiritual children came to Bishop Sergius from other cities and countries where his duties carried him.

In 1939, at the beginning of the Second World War, Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Germans. Regardless of the dangers, the bold pastor continued to serve molebens every day for the end of the war. When the local authorities wanted the bishop to give a presentation at the opening of the conference of the Committee for the liberation of the peoples of Russia, he was not afraid to decline the offer because he loved his motherland. This was a very bold move. Nevertheless, nothing came of it. Finally in 1945, Prague was liberated by the soviet forces. But this victory was soon replaced with a new disaster—arrests soon began, which included Russian émigrés. Some one from Bishop Sergius’s flock offered to move to the West to avoid danger, but he declined, saying, “No. They will return me to Russia, and I will die there. I will remain in the place where God placed me.”

That is what happened, only after a few years. Before then, the archpastor would have to hear much slander aimed at him and experience several interrogations. In 1946, Patriarch Alexy I, with whom he had once studied at the Moscow Theological Academy, elevated him to the rank of archbishop and appointed him to the Vienna cathedra, and in 1948 he was made archbishop of Berlin and Germany.

Bishop Sergius was able to return to Russia only in 1950, when he was appointed archbishop of Kazan and Chistopol. His long-held dream had now come true. “I am happy that I am finally home, in my native land, and I can give the rest of my life to the service of my native people,” he wrote of this. True, he was not able to serve his native land very long—on December 18, 1952, Bishop Sergius departed to the Lord. The beloved archpastor was buried in Kazan in Arsov field, next to the cemetery church. This year marks sixty-five years since his repose.

Archbishop Sergius on spiritual life in the world

Although Archbishop Sergius himself was a monk, he spent the larger part of his service with people living in the world. He left us several valuable publications, which could be united by the common theme of spiritual life in the world. This theme, which so interested the archpastor then, is no less important for us today. It is in this field (everyday life in the world), considered the archbishop, that the fiercest spiritual battle takes place, and possibly the most significant victories are won. The podvig that seems ephemerally small and even unnoticeable to us turns out to be enormous and requiring great valor, and capable of changing very much for people’s common good.

“Man is created for happiness,” affirmed Vladyka Sergius. But we look for this happiness in all the wrong places. The desire itself to be happy is a reflection of the blessedness that was in Paradise. The reason the first people were cast out of paradise is sin. And today also it is sin that hinders us from “joyfully walking the earth.” This means that man’s happiness begins were sin ends.

Only those who have a peaceful heart can rejoice here, on earth. This is the joy of the Holy Spirit; this is that Heaven on earth about which many dream, but do not know how to acquire it. And all of this is not only obtainable, but is also the direct calling of each of us; after all, we are God’s emissaries on earth. Each of us here has his own specific mission, but all of these missions can be boiled down to one: “to bear the light of Truth,” sharing it with others.

Everyone is called to carry on a spiritual struggle, to strive for perfection, in the place where God has place him. Right there, in that very ordinary, everyday life, are the most important spiritual podvigs (ascetic feats) accomplished. And in Archbishop Sergius’s view, everyday family life is even the most convenient place to do this—for in those very family circumstances we behave ourselves the most naturally and unpretentiously. Here the rough spots of our souls are “sanded down” or “polished off” the best, and our inadequacies are healed. Sins are struggled with best of all when they are seen; but in society we usually behave ourselves differently, hiding all the worst in ourselves.

It is in peoples’ interpersonal relationships, considered Vladyka, that the main thing people are called to comes out. He called community life one of God’s gifts that are hard to obtain on our own. In communion with others, we both reveal our own individuality and enrich ourselves with that of others. However, often due to our sinfulness people focus their attention on only some incidental, negative traits in other people. But these traits are really secondary and not the main thing in people; the main thing is what comes from God. “We have to find the treasure hidden in every heart,” Vladyka Sergius taught. Only then can people become whole, members of the Body of Christ, and will be happy already here, on earth.

Citations from the works of Archbishop Sergius:

Man was created for happiness, and only through everyday victories can he obtain joy and a state that brings light to everyone and himself…

***

All of life is in people’s interpersonal relationships. We have to illumine them with the light of Christ’s Truth.

***

If there is peace in the soul, that joy will never be taken away. Lack of peace will never bring happiness.

***

Life is a great labor. We have to learn to live wisely in Christ, and then everything around us will make sense and acqire value for eternity.

***

Every victory over sin is a victory over ourselves and others for the mutual understanding of the life of all people.

***

The cultivation of the inner man is done not in the world of astounding podvigs, but in everyday life.

***

The presence of happiness in life lies in the presence of our spiritual life. No matter how beautiful the forms of life may be, if a person does not conquer sin in himself, he will not obtain true happiness.

***

The matter is not our in littleness, but in our lack of desire to take on responsibility.

***

People are God’s flowers—we, like the bees, have to know how to gather honey from these flowers, to enrich ourselves with the individuality of others, and reveal our own individuality to others.

***

There is beauty in every person, and only our sinfulness prevents us from seeing it.

***

Community life is God’s gift, and it is an ascetic labor to make ourselves sociable if we are not sociable for the sake of supplementing our [personality’s] poverty.

***

We have to find the hidden treasure in every heart. People often search for treasures, but not those of the soul; but we need to search for the treasures of the soul. Some may ask, what for? We reply, in order to become rich.

***

It is our task to turn our attention not to the external, but to search in ourselves and others for what we have from God.

***

Our souls are created for eternity, but we take absolutely no care for them. We strive to acquire all possible treasures, except for the treasures of eternity. We are poor merchants. We put a cheap price on our souls.

***

The Christian’s direct task is the realization of divine life on earth.

***

It is impossible to find goodness if we don’t walk on the path of Christ. Only by following Christ can a person find his own goodness.

***

Divine life is not a theoretical ideal, but a practical requirement.

***

Unity among people is the thread tossed up from earth to heaven, to God, to the Unifying Center. The unity coming from one heart to another is directed to one center—to God; for unity among people is life, while division is death.

***

With sin, a person is as if afraid of another person, and does not step joyfully on the earth. He thinks to himself how not to meet up with one or another person… By having conquered sin, a person can easily approach another person and infect him with goodness.

***

We have to know how to illumine our mutual relationships with the light of Christ’s truth, so that we might bring them goodness. By searching out what is common to us from God, we become God’s co-workers on earth.

***

What is from God is the real goodness here, on earth—it is joy in the Holy Spirit. Then heavenly life will open up for us.