The following English translation of a lecture by Bishop Athanasius (Yevtich) of Zahumlje and Herzegovina was offered to our readers by Orthodox Ethos.

It is with gratefulness to God and relief that Orthodox Ethos is finally able to publish in the English language the following exceptional lecture by Bishop Athanasius Yevtich on the well-known and well-utilized article “On the Limits of the Church” by the ever-memorable patristic scholar and Orthodox Theologian, Fr. George Florovsky. For years, since shortly after its publication in the Greek Journal Theologia, we had seen the importance and need for a translation of this lecture for our English-speaking brethren. We are indebted to our friend and associate Nicholas Pantelopoulos for this excellent translation, which we know will be of great interest to many who have been confused or misled as to the Orthodox teaching on the nature and boundaries of the Church. Bishop Athanasius’ contribution to the inter-Orthodox exchange on the proper understanding of the nature of the unity and boundaries of the Church is sure to be received with gratefulness by many and anguish by a few, but with interest by all.

—Fr. Peter Heers, Editor of Orthodox Ethos

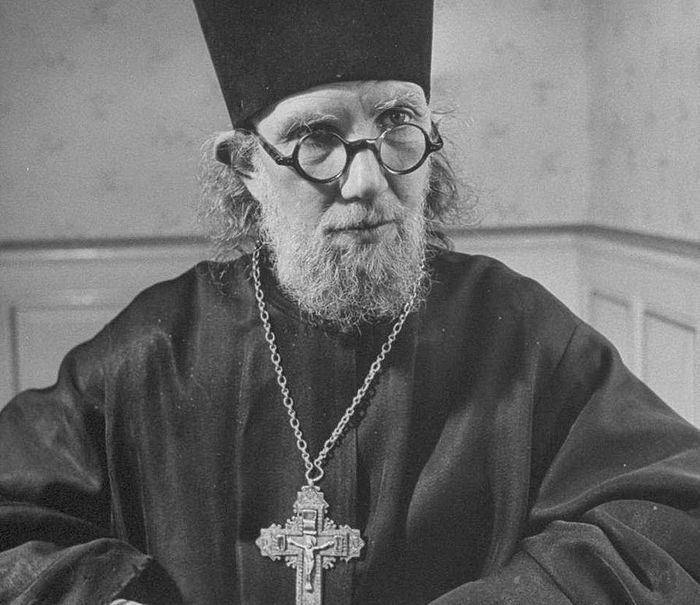

It will be difficult for me to duly expound on the magnitude and importance of Fr. George Florovsky, the “ecumenical first-priest”, as he was referred to by his student, bishop Daniel (Krstich).1 Nonetheless, with great love and gratitude to God and to Fr. George, I will always remember when as a hieromonk I served Divine Liturgy with this great father, celebrant and theologian, in a 9th-century Byzantine church, in the monastery of Saint Nicodemus in Athens, which became known in the 19th century as the “Russian Church”. Afterwards, with the providence and grace of God, I had the honor to succeed him for three years (1970-1972) at the Orthodox Theological Institute of Saint Sergius in Paris, as chair of Patristics, along with Fr. Andrew Fyrilla. Before I met him, however, and got acquainted with him on a personal level, Fr. Justin Popovich spoke frequently about Fr. George Florovsky, with whom he spent years together during the German invasion in Serbia, when they would meet and talk. Fr. Justin Popovich would call Fr. George Florovsky an “icon on the iconostasis of Orthodox theology of the modern age.”

The organizers of this present colloquium asked me to speak on the subject, “Fr. George Florovsky on the Boundaries of the Church”. It concerns a very difficult subject and I will try to speak as objectively as I can, with complete respect towards Fr. George Florovsky, but with a critical approach towards the position that he formulated in his article. In previous sessions, there were already some presentations about Fr. Florovsky’s ecclesiology, which happens to be rich and multi-dimensional. His article on the “Boundaries of the Church”,2 in my opinion constitutes an early phase in Fr. George Florovsky’s evolution. It was written in Paris on the feast day of Saint Sergius in 1933. It was published in English, then in Russian, and then in French and Serbian. There exists a translation in Greek3. Without a doubt, Fr. Florovsky’s article is written within the framework of the ecumenical movement, which also is a leading subject for his time as well as our own. This fact is highlighted by the author himself, as he refers to an article of his, “On the Reunification of Christians”, which was published in a volume collection in 1933 in Paris, just as another older article of his, “The Problems of Christian Unification”.4

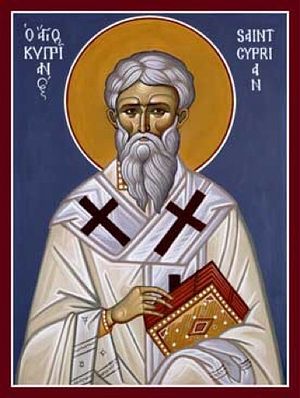

We will not continue the exhaustive analysis of this article by Fr. George Florovsky. The author briefly mentions in the text the apostolic and patristic events concerning the unity of the Church, by placing special emphasis on Saint Cyprian of Carthage. He presents and exercises criticism on the positions of Cyprian, and then goes on to Saint Augustine and the practice of the Church in relation to the acceptance of heretics. Subsequently, the author refers to modern Russian theologians. Thus, on the one hand there is a mention of Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) and of Archbishop Hilarion (Troitsky), who considered that the charismatic boundaries of the Church coincide with the canonical. On the other hand, he refers to [the Russian philosopher] Aleksey Khomyakov and Metropolitan Philaret (Drozdov) of Moscow, who considered that the charismatic and canonical borders of the Church did not coincide. I also remember Fr. Justin Popovich, who would say that the more correct and theologically Orthodox position was held by Metropolitan Anthony and Archbishop Hilarion; in other words, that the charismatic and canonical boundaries of the Church coincide. It is interesting that in the same year, of 1933, an article was published, written by bishop Sergius (Stragorodsky), later Patriarch of Russia, which Fr. George Florovsky most likely did not have a chance to consider. These two theologians [Metropolitan Anthony and Archbishop Hilarion], although they wrote independently from each other, almost echo the same views word for word, resulting in concurring opinions on the limits of the Church. Fr. George Florovsky elicits the Greek theologians, [Christos] Androutsos and [Konstantinos] Diovouniotis—rather old and conservative theologians—and mostly refers to them in relation to a commentary of his concerning economy of the Church. We must note that this commentary in particular was also weak. Fr. Florovsky does not proceed to analyze the great Fathers of the Church, although in approximately the same period he writes some of his greatest and famous works on Patristics, such as, “The Eastern Fathers of the 4th century”,5 and “The Byzantine Fathers of the 6th—8th centuries”.6

In his article, Fr. George Florovsky is not particularly preoccupied with an analysis of what he calls, and what truly is, the practice of the Church in the reception of heretics, but rather how this practice was formed. In my opinion, this is an important shortcoming of this particular article, since faith and theology is revealed in the practice of the Church, and it must be taken into serious consideration when we speak about the boundaries of the Church.

Recently, professor [Constantine] Zaitsev of the [Moscow Theological] Academy in the Holy Trinity[-St. Sergius Lavra] wrote a substantial and expansive work on the boundaries of the Church in his 12th volume of the New Orthodox Encyclopedia (published by the Patriarchate of Moscow with the blessing of the Patriarch). There, he mentions the opinions of many Fathers of the Church and contemporary Russian theologians. At the end of this reference, he briefly refers to the “Basic Principles of the Attitude of the Russian Orthodox Church Toward the Other Christian Confessions” (“Основные принципы отношения Русской Церкби к инославию”), an official text published recently in Moscow in 2000 by the Holy Synod of the Russian Church. In a very curious way, Zaitsev summarizes the opinions of the Council expressed by this official text. Without having to refer to his opinions at length, we will only mention that he repeats the views of Fr. Florovsky. At the end of his text, Professor Zaitsev arrives at the same assumption as the one reached by Fr. Florovsky, that the canonical and charismatic limits of the Church do not coincide, and adds, “Starting from the position expressed in the text, ‘Basic Principles of the Attitude of the Russian Orthodox Church Toward the Other Christian Confessions’, it seems more defensible from an ecclesiastical and also historical and theological point of view the position held by Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow, Patriarch Sergius, and Fr. Florovsky. As it pertained to other points of view, which he characterizes as “rigid akriveia”[exactitude], referring primarily to Saint Cyprian: “Although these positions are founded upon correct theological foundations, they require, however, much better definition”. In other words, Zaitsev equated the position of the Russian Church with that of Florovsky and almost presents the same opinion.

We must point out, nonetheless, that after several readings of Fr. Florovsky’s article, we have the impression that he wrote this text at a young age, when he had been a priest for no more than a year, and that this text does not represent a complete expression of his ecclesiological view. Florovsky presents the position of Saint Cyprian, then quickly passes over to the opinion of Saint Augustine and accepts his ecclesiological views without adequate critical thought. In particular, it seems he adopts the views on ex opera operato and opera operantis, and recommends that the Orthodox accept Augustine’s opinion concerning the limits of the Church, where the charismatic and canonical boundaries do not coincide. On the other hand, the analysis of Saint Cyprian that Fr. Florovsky provides is one-sided.7 Fr. George Florovsky did not carefully examine, in parallel to the texts of Cyprian, his very important letter to Saint Firmilianus of Caesarea (230-268), the predecessor of Saint Basil, and also the letter to Saint Dionysius of Alexandria. These two Fathers, both contemporaries of Saint Cyprian, do not accept the opinion of Augustine and Pope Stephen of Rome. For without a doubt they speak about coinciding charismatic and canonical limits of the Church even if they do not refer to them in this manner.

When Florovsky examines the works of Cyprian, and especially those of Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitsky, (who as we said, considers the canonical and charismatic limits of the Church to be the same), sometimes we have the impression that he exaggerates. Likewise, it appears, when he talks about the practice of the Church in relation to the reception of heretics. For example, the then young theologian and priest George Florovsky observes, “One may ask who gave the Church this right…” to accept heretics in this manner, meaning here the application of ecclesiastical economy instead of the exactitude supported by Cyprian. In other words, the practice of the Church does not impose on all heretics to be re-baptized, as Saint Cyprian demanded. To such a question, we dare juxtapose the following counter-question: Who gave the right to Fr. Florovsky to put such questions to the Church? Or in other words, to direct this question to St. Basil the Great, the great hierarch, theologian and canonist of the Church, whose opinion on the application of economy in the acceptance of heretics is what the Church ultimately applies. This position of his concerning the use of economy does not indicate an acceptance of a “Church outside the limits of the Church” (a phrase belonging to Fr. Florovsky), because economy of the Church, the act of acceptance of heretics to the Church in three different phases or in three different modes, was conveyed perfectly in the canonical letter of Basil the Great to Amphilochios of Iconium (Epistle no. 188). It is apparent that ecclesiastical economy has been taken into consideration in a much greater degree than Fr. Florovsky assumes. Florovsky concludes that the economy of the Church is simply a pedagogical/pastoral measure, related simply to the philanthropy of the Church. As if philanthropy is something arbitrary, an unimportant detail! Yet, for Basil the Great and the Fathers of the Church, economy in the Church becomes apparent and must be applied as a demonstration and revelation of the Divine Economy of Salvation, as an expression of Divine philanthropy. For the Church, this is not simply a word, but a reality with a profound theological and ecclesiological context. It is not simply a dispensation—dispensatio as it is rendered by Hieronymus in Latin and in other western languages. Economy is Divine Economy. The great Fathers like Chrysostom or Evlogios of Alexandria (6th C) and many others speak in detail about what is Divine Economy.8 Firstly, this economy means that God became flesh, condescending towards us without leaving His Godhead and His throne. Christ “emptied himself” (Philip. 2:8) through the incarnation and inhomination; this emptying of Divine love is recognized as economy, the Divine Economy of Grace, the work of the philanthropy of the Holy Trinity.9

We believe that the article on the Limits of the Church by Fr. George Florovsky, without diminishing it, was “unseasoned”, even though it was not exactly pioneering or a first of its kind—since this path was followed by Khomyakov and Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow, on whom Florovsky is grounded and to whom he refers. But we will point out two essential elements, or shall we say, “occurrences” (Fr. Florovsky points out exactly that the theology of the Fathers, like Saint Gregory Palamas, is a “theology of occurrences”), two facts that constitute the essence of Orthodox ecclesiology and the practice of the Church for the admission of heretics, which Florovsky did not take into consideration.

First, the limits of the Church of God in Christ Jesus the Theanthropos are the “Boundaries” of his boundless Divine Economy of salvation, the limits of the boundless philanthropy of God; and these limits should not be separated from the limits of Grace of the All-Holy Spirit, the Comforter, in the Church. These limits cannot be narrower than the narrowest limits of the Cross and the Resurrection of the Incarnated Christ, in body and as Body, as the Church, as fullness, revealing the “fullness of Him who fills all in all.” (Ephesians 1:22-23)10

Second, these economic—charismatic limits of the Church, in a paradoxical way, cannot and should not exclude the exceedingly important consequence of the liturgical—canonical limits of the Church. Without expanding further, I will simply summarize that this consequence is derived from the event of Liturgy as Communion, as participation in what we call the Church, which is communion and participation of the members of the Church in the Holy Eucharist, in Liturgy. For this reason, we Orthodox cannot accept intercommunion. Not out of some anti-ecumenist stance,11 but exactly because in the Holy Eucharist, as a gathering of the Church in Christ through the Holy Spirit, the charismatic limits of the Economy of salvation of the Holy Trinity and the canonical-charismatic limits of the Church coincide. In this sense Saint Ireneaus of Lyons wrote, when he expressed this view clearly and with theological precision, “But our opinion is in accordance with the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn establishes our opinion” (Against Heresies, Book 4, Chap. 18:5)12. This exactly coincides with what even Fr. George Florovsky, Fr. Alexander Schmemann and many other theologians emphasize, when they say, lex orandi est lex credenda, or in other words, the canon of worship is the canon of faith, and vice-versa.

Here, of course, I would say that there appears to be an antinomy; for it must be said that an antinomy fits more with the theological view of Fr. Florovsky because of the position he took in his article on the limits of the Church. And this is how it should be, since there is an organic unity between the Christological-pneumatological, and the soteriological-ecclesiological substance, life, and salvation in the Church. This is what is revealed in the mysteries [sacraments] of the Church—Baptism, Chrismation, Eucharist, Priesthood—which constitute the Mystery of the Fullness of the Church. The Mysteries of the Church cannot be above or outside the Church, because the Church is the fundamental Mystery, the Mystery of Christ, per Apostle Paul and Saint Maximus, from which spring all the other mysteries [sacraments], which project onto Him. All these things are revealed and are experienced in the Mystery of the gathering of the Church in the Holy Eucharist, and as a unity of faith and communion in the Holy Spirit, which we confess, glorify and live every time we proclaim together the “Our Father” during Holy Eucharist, and partake together in Holy Communion. These are the elements that elude to and constitute the core and the essence of Saint Cyprian’s view. This is what Saint Cyprian expresses in his known letter: “All heretics do not have the power and the right to baptize (…) because as enemies of the Lord, they apostatized from the love and unity of the Catholic Church (…). The Church is one, and being one, cannot be in and outside (que et intus esse et foris non potest) (…) The Church cannot be outside Herself (fortis autem non esse Ecclesiam), nor can She be broken and divided into something opposite to herself, because She is unity in the house of the God.” Cyprian, therefore, theologically and ecclesiologically connects the unity of Baptism with the unity of the Church, which reveals the “unity of Eucharist”. He closely connects the “grace of one ecclesiastical baptism” (unici ecclesiastici baptismi gratiam), with “the unity of the Church” (Ecclesiae unitatem) and the “inseparable Mystery of unity” (inseparabile unitatis sacramentum) with the Eucharist, as Body and Blood of Christ, where “Christian concord is connected with the inseparable love, as it is shown in the Sacrifice of the Lord” (unianimitatem christianam firma sibi adque inseparabilio caritatem conexam etiam ipsa Dominica sacrificial declarant) (Epistle 69, 1.3-5). Thus, for Cyprian, the “one baptism” is inseparable from the unity of the Church in the Eucharist, which is the unity of all in faith, hope and love. In one word, unity of all in the Holy Trinity, per the Apostle: endeavoring to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called in one hope of your calling; one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is above all, and through all, and in you all. (Eph. 4:1-6).

The Fathers of the Church, and contemporaries of Saint Cyprian, and the consequent practice of the Church, bear witness to the position of Cyprian, since the non-recognition of the baptism of heretics outside the Church was never rejected by the Church of the East.13 This is recognized in their own way by Fr. George Florovsky and his student Metropolitan John (Zizioulas) of Pergamon. In the Christian east and in Africa, just as Saint Cyprian, they acknowledge that there is no salvific Baptism among heretics and schismatics (as it is confirmed by several Ecclesiastical Synods: Carthage of 220, Iconium of Asia Minor of 235, followed by Antioch of Syria and others14), because the Holy Spirit is not imparted outside the Church. She [the Church] is the one that contains the fullness of the faith in the Holy Trinity and in Christ, and the fullness of Grace and communion in Church, which is the fullness of salvation, and the fullness of communion with the Holy Trinity.

Saint Firmilianus, bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia (230-268)15 and a contemporary of Cyprian, was against Stephen, who as bishop of Rome recognized the baptism of heretics. He wrote like Cyprian and supported the same theology on the One Baptism. Firmilianus writes about One Baptism in the Church as a “bond of unity”, and as “divine unity” (divina unitate). As he points out, “For as even the Lord who dwells in us is one and the same. He everywhere joins His own people in the bond of unity (vincula unitatis)(…). Those souls, however, who have departed from the unity of God cannot come into the unity of the Holy Trinity”—and he refers to the Lord’s prayer for this unity with the Father (John 17:21). “Whence it appears that this tradition (of Stephan) is of men which maintains heretics, and asserts that they have baptism, which belongs to the Church alone (…). Those who do not recognize and do not confess the True God the Father can neither know the truth for the Son and the Holy Spirit (…). Moreover, all other heretics, if they have separated themselves from the Church of God, can have nothing of power or of grace, since all power and grace are established in the Church where the presbyters preside”—who possess both the power of baptizing, “and of imposition of hands, and of ordaining (ordinandi). For as a heretic may not lawfully ordain nor lay on hands, so neither may he baptize, nor do anything holily or spiritually. For heretics are “alien from spiritual and deifying sanctity” (aliens sit a spirtali et deifica sanctitate) (…) Spiritual birth cannot be without the Spirit (spiritualem nativitatem). Thus, Apostle Paul baptized anew with a spiritual baptism those who had already been baptized by John before the Holy Spirit had been sent by the Lord, and so laid hands on them that they might receive the Holy Spirit. (Acts 19: 2-6) (…). But if it is spiritual, how can baptism be spiritual with those among whom there is no Holy Spirit? (…) The bride of Christ is one, which is the (Catholic) Church, it is she herself who alone bears sons of God. (…). If therefore, Christ is with us, then Christ is not with the heretics. Then it is obvious they are opponents of Christ, and if we gather with Christ, they disperse (Matt. 12:30)(…) But we join custom to truth, and to the Romans’ custom (of Pope Stephan) we oppose custom, but the custom of truth. We accept that which Christ and the Apostles delivered to us from the beginning. We who knew none but one Church of God and accounted no baptism holy except that of the holy Church (…). When they (i.e. the heretics) come baptized to us, they are then baptized with the only and true baptism of the Catholic Church (unico et vero Ecclesiae Catholicae baptism) and obtain the regeneration of the layer of life (Epistle 75, 2.3.6.7.9.13.14.19.22).16

Consequently, Saint Firmilianus stresses that he who is separated from the Church is foreign to spiritual grace; foreign to the gift and deifying grace of the Holy Spirit. It is not enough, says Saint Firmilianus, to offer names (i.e.: the type of the baptism) in order that sanctification and salvation is truly offered through baptism. These thoughts are repeated by Saint Athanasius of Alexandria in his known work, “Contra Arianos”: “And these too hazard the fullness of the mystery, I mean Baptism; for if the consecration is given to us into the Name of Father and Son, and they do not confess a true Father, because they deny what is from Him and like His Essence, and deny also the true Son, and name another of their own framing as created out of nothing—is not the rite administered by them altogether empty and unprofitable, making a show, but in reality being no help towards religion? (…) For not he who simply says, ‘O Lord,’ gives Baptism; but he who with the Name has also the right faith. On this account, therefore our Saviour also did not simply command to baptize, but first says, ‘Teach;’ then thus: ‘Baptize in the Name of Father, and Son, and Holy Ghost;’ that the right faith might follow upon learning, and together with faith might come the consecration of Baptism.” (42: 4-11 and 15-21).17 “There are many other heresies too, which use the words only, but not in a right sense, as I have said, nor with sound faith, and in consequence the water which they administer is unprofitable, as deficient in piety, so that he who is sprinkled by them is polluted by irreligion rather than redeemed” (43: 22-26).

This is a very important position by St. Athanasius the Great and must be taken seriously into account today when we meet people in the framework of the ecumenical movement who claim that “the limits of the Church is Baptism”.18 By not taking into account the correct—orthodox faith and confession of doctrines, which if some do not possess, they are not Orthodox. They are schismatics, separated from the fullness of the God-given gifts, charismas and operations, grace and unity in the Eucharist which is the identity of the Church in Christ, through the grace of the Holy Spirit, for the glory of God and Father and the salvation of the world.

Let us refer to the opinions of another contemporary of Cyprian, Saint Dionysius the Great, Archbishop of Alexandria (247-264). In his letter to Philemon, a priest of Pope Sextus, he writes: “I received this rule and ordinance from our blessed father, Heraclas. For those who came over from heresies, although they had apostatized from the Church—or rather had not apostatized, but seemed to meet with them, yet were charged with resorting to some false teacher—when he had expelled them from the Church he did not receive them back, though they entreated for it, until they had publicly reported all things which they had heard from their adversaries; but then he received them without requiring of them another baptism. For they had formerly received the Holy Spirit from him.”19 Hence, according to Dionysius, we should not rebaptize those who were once baptized in the Church, even if they have consequently lapsed. Jerome confesses that Dionysius “agreed with Cyprian and with the decisions of the Council of Africa, and wrote many letters in relation to this subject.” (De viris illustribus, 69)20. In a not very well-known epistle to Dionysius, “Epistle to Dionysius, Stephen and the presbyters of the Church of Rome”,21 he notes: “Those who are baptized in the name of the three persons (of the Holy Trinity)—of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit—should not be rebaptized, even if they were baptized by heretics, but only when these heretics do not confess the three persons. Those who come to the Church from other heresies, we baptize.”

As we can see, Saint Dionysius the Great expresses the same opinion with Cyprian and later with Athanasius the Great. But as we shall subsequently show, as Saint Dionysius confessed, Basil the Great expressed the opinion, which he also applied in practice, that it is not necessary to rebaptize just anyone who comes to the Church from various heresies and schisms. In Epistle II to Pope Sextus, Dionysius refers to the case when a believer “came to me weeping, and bewailing himself; and falling at my feet he acknowledged and protested that the baptism with which he had been baptized among the heretics was not of this character, nor in any respect like this, because it was full of impiety and blasphemy. And he said that his soul was now pierced with sorrow, and that he had not confidence to lift his eyes to God, because he had set out from those impious words and deeds. And on this account, he besought that he might receive this most perfect purification, and reception and grace. But I did not dare to do this; and said that his long communion was sufficient for this. For I should not dare to renew from the beginning one who had heard the giving of thanks and joined in repeating the Amen; who had stood by the table and had stretched forth his hands to receive the blessed food; and who had received it, and partaken for a long while of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. But I exhorted him to be of good courage, and to approach the partaking of the saints with firm faith and good hope.”22

This example shows that the Church’s practice of accepting certain groups of heretics into the Church without rebaptizing had already begun from that time, and continues until today. This practice is already witnessed in the 3rd and 4th century and is expounded by Basil the Great, as will see further. At the same time, however, it is stressed that for the practice of admission of heretics and schismatics into the Church, basic and fundamental was their unification with the oneness and communion of the Church and not any “objective” recognition of the sacraments of heretics. Thus, it appears that the principle in force is the one of Cyprian. That canonical and charismatic boundaries of the Church coincide, and are especially revealed in practice in the One Eucharist of the real Church, in which those who approach partake in communion, and in this manner, belong to the Church. For there is no Church outside the Eucharist, outside the Liturgical communion. This is the content and meaning of the canonical tradition of the Church. When the unity of the Church has been sundered, at exactly that moment, the canons are applied—such as economy—to protect and rebuild unity.

This same canonical practice and theological confession is clearly what Basil the Great employs and expresses in his first canonical epistle to Amphilochius of Iconium (Epistle 183). We will not refer to it entirely. Nevertheless, it has been summarized in all the collections on Canon Law of the Orthodox Church as Canon I of Basil the Great, based on the First Ecumenical Council and reiterated in a special manner in Canon VII of the Second Ecumenical Council, as in the case of Canon XCV (95) of the Council in Trullo. Basil the Great observes in the beginning of this (letter) canon: “As to your enquiry about the Cathari, a statement has already been made, and you have properly reminded me that it is right to follow the custom obtaining in each region, because those who at the time gave a decision on these points held different opinions concerning their baptism. But the baptism of the Pepuzeni (i.e.: Montanists) seems to me to have no authority; and I am astonished how this can have escaped Dionysius, acquainted as he was with the canons. The old authorities decided to accept that baptism which in nowise errs from the faith. Thus, they used the names of heresies, of schisms, and of unlawful congregations. By heresies, they meant men who were altogether broken off and alienated in matters relating to the actual faith; by schisms, men who had separated for some ecclesiastical reasons and questions capable of mutual solution; by unlawful congregations, gatherings held by disorderly presbyters or bishops or by uninstructed laymen.”23 Saint Basil refers to examples of unlawful congregations and schisms, but refers to the Manichæans, of the Valentinians, of the Marcionites, and “Pepuzeni” (Montanists) as heresies, which have substantial differences in faith from the Church. And Saint Basil continues saying, “So it seemed good to the ancient authorities to reject the baptism of heretics altogether, but to admit that of schismatics, on the ground that they still belonged to the Church. As to those who assembled in unlawful congregations, their decision was to join them again to the Church, after they had been brought to a better state by proper repentance and rebuke, and so, in many cases, when men in orders had rebelled with the disorderly, to receive them on their repentance, into the same rank.” Then, concerning the Montanists, Saint Basil says, “What ground is there, then, for the acceptance of the baptism of men who baptize into the Father and the Son and Montanus or Priscilla? For those who have not been baptized into the names delivered to us have not been baptized at all. So that, although this escaped the vigilance of the great Dionysius, we must by no means imitate his error. The absurdity of the position is obvious in a moment, and evident to all who are gifted with even a small share of reasoning capacity.”24 Consequently, the baptism of heretics cannot be accepted.

More specifically, Basil continues to expound the practice (praxis) of the Church: “The Cathari are schismatics; but it seemed good to the ancient authorities, I mean Cyprian and our own Firmilian, to reject all these, Cathari, Encratites, and Hydroparastatæ, by one common condemnation, because the origin of separation arose through schism, and those who had apostatized from the Church had no longer on them the grace of the Holy Spirit, for it ceased to be imparted when the continuity was broken. The first separatists had received their ordination from the fathers, and possessed the spiritual gift by the laying on of their hands. But they who were broken off had become laymen, and, because they are no longer able to confer on others that grace of the Holy Spirit from which they themselves are fallen away, they had no authority either to baptize or to ordain. And therefore, those who were from time to time baptized by them, were ordered, as though baptized by laymen, to come to the church to be purified by the Church’s true baptism. Nevertheless, since it has seemed to some of those of Asia that, for the sake of management of the majority, their baptism should be accepted, let it be accepted.”25

These last words of Basil the Great show that economy in the Church is applied differently each time, in accordance to the local traditions and customs. Saint Basil respected this practice, even though he believed that we should employ akriveia [exactitude]. Basil recalls the same for the Encratites, in canon 57,26 for whom he literally notes: “We re-baptize them all. If it be forbidden with you, (as it is at Rome)27 for prudential causes, yet let reason prevail.” This freedom of Basil the Great, a freedom in the Holy Spirit, and his greatness of heart with a fullness of pastoral duty of a hierarch and theologian, pastor, and canonist, was not only particular to him, but also characterized all the other Fathers before and after him. This rule was followed as canonical and liturgical wisdom for the edification of the Church. This is why the authority of Basil the Great is so great. Basil concludes at the end of Canon I, “On every ground let it be enjoined that those who come to us from their baptism be anointed in the presence of the faithful, and only on these terms approach the mysteries.”

This practice is expressed by Basil the Great in Canons I and XLVII(47) and shows that ecclesiastical economy can transcend lawful exactitude [akriveia]. In this case, an unfulfilled baptism of schismatics is not repeated, but received with the Holy Oil of the Holy Spirit [chrismation]; especially bishops accompanied by their flock, so that they may be united to the fullness (pleroma) of the Church, where the Holy Spirit revivifies and completes all that is dead and lacking in them.28 Thus we can say with confidence that the Holy Mysteries do not exist outside or above the Church and their forms are not the criterion of ecclesiality and salvation. However, the Church is the criterion and the seal of all those who come to the Church. Consequently, the Church as a summarized salvation of Christ is the only path of salvation, the Mother of all of us (Galatians 4:26, Hebrews 12:22-24, and Methodius of Mount Olympus, Symposium 8: 5-8).

The position and practice of the Church is traced in the Holy Canons of the Fathers and the Synods (and we already mentioned Canon VIII of Nicaea, Canon VII of Constantinople, and Canon XCV (95) of the Council in Trullo), as well as the Offices of the Church for the reception of heretics. We have as examples Timotheos of Constantinople, 6th C, repeated by George the Hieromonk, and John of Damascus, Methodius of Constantinople, the Book of Prayers (Euchologion) of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the “Interpretation of the commandments of the Lord” (Discourse LXIII, Pandekti) of Nikon Mavroreitis29, and others. All these [views and practices] were later introduced as canonical collections of the Orthodox Church and were translated into Slavonic—“The Rudder” of Ephraim and the “Nomokanon” of Saint Sava—as in other languages.

However, it is characteristic that Canon VII of the Second Ecumenical council begins with the words of the Acts of the Apostles, with the well-known verse 2:46-47, which expresses the ecclesiological-Eucharistic truth: And the Lord added to the church daily such as should be saved. The same canon restates the Epistle of Patriarch Gennadius of Constantinople (5th century) to Martyrius of Antioch and is literally repeated in Canon XCV (95) of the Council in Trullo, where it uses the words from Acts: THOSE who from the heretics come over to orthodoxy, and to the number of those who should be saved, we receive according to the following order and custom.30 This expresses the attitude of the Acts of the Apostles. These sacred canons and the practice of the Church add that those who come to the Church in repentance with their rejection of heresy or schism are received with the laying of hands and with Holy Oil, with the phonation, “Seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit”, and thereafter they receive Holy Communion. The same happens as mentioned in Canon I of Basil the Great. This means that only through entry into the Church, those who were not yet [received] are incorporated in the unity and communion of the Church—in the fellowship of the saved.

To not expound further, we could make the following conclusions: the most significant is not what we recognize when we admit heretics, whom we are obligated to baptize, or others who should receive chrismation with Holy Oil. Rejection of heresy and repentance on their part is obviously preconditional, but the most important is their entrance and union with the Church.31 Thus unfortunately Fr. George Florovsky fails to relate communion and union with the Church, in this essay about the “Boundaries of the Church”.

Hilarion (Troitsky)32 speaks about the admission of heretics in the Church for their gathering in the unity of the Church, in his Epistle on 18 of January 1917 to the American Robert Gardiner, the secretary of “Faith and Order” committee and responsible to organize the Worldwide Conference of Christians (it was at the beginning of the Ecumenical movement). We will not go through the entire epistle.33 We will only note the basic formulations of Archbishop Hilarion: The meaning of salvation in the Church is the coming of a person into Her unity, whereas the manner of admission is a secondary matter. Sacramental-charismatic and salvific significance is at the level of the very same communion in the Church, by which one is received into the unity of the Church (repentance, laying of hands, Chrismation), and consequently, with participation in the Holy Eucharist, the sacramental and ecclesiological Body of Christ.

Therefore, most important is the Mystery of Christ, which is the Church. For this reason, admission to the Church, union with Her, signifies the entry into the fullness of the Church, the fullness of Grace, the fullness of salvation, the fullness of the incorporation into the Body Christ. It is truly an incorporation, an embodiment and a churchification in the Body of the Theanthropos (as Saint Justin Popovich would say). This means entry into the full communion of the Holy Trinity, which is revealed and in which we participate in the gathering of the Church, in Liturgy as the sacrament of the Supper of the Kingdom, here and now, and a foretaste and participation in the eschatological Kingdom.

Fr. Florovsky, as we know, referred to the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, the Church that unites us all, and which is the “House of God” (in his well-known essay, “The House of the Father”34), the dwelling of the Holy Spirit, the pillar and ground of the Truth. The Faith of the Church, the great Mystery of Faith, is not simply a “confession”, as some uphold today, but is the selfsame Church. The correct faith—Orthodoxy—is an action of entry into the fullness of the Church, even if it alone does not constitute a sufficient provision for salvation. For it must always express the deeper entry into the unity of the Church.35 Thus, prior to Holy Communion, in the fullness of liturgical language and practice, we petition, “The unity of faith and the communion of the Holy Spirit…”.

Concluding this brief study, we will cite two fragments from the same work of Fr. George Florovsky: “In the ancient Church the ceremony of initiation was not differentiated. The three sacraments go together: Baptism, Holy Chrismation and Divine Liturgy. The initiation described by Saint Cyril and later by Cavasilas is comprised of all three. (…) The sacramental life of believers is the edification of the Church. Through sacraments and in them, the new life of Christ is extended and conferred to the members of His Body.”36

In this context, it is valuable to note what can be considered as a confession of the very same Fr. George Florovsky: “As a member and a priest of the Orthodox Church, I believe that the Church in which I was baptized and raised ‘is’ in very truth ‘the Church’, i.e. ‘the true’ Church and the ‘only’ true Church. And I believe this for many reasons: owing to personal conviction and to internal confirmation of the Spirit, who breathes into the Sacraments of the Church. Therefore, I am compelled to regard all other Christian Churches as defective, and in many cases I can define the deficiencies of these other Churches accurately enough. Therefore, for me, Christian reunion is simply universal conversion to Orthodoxy. (…) “Judgment” has been given to the Son. No one has been appointed to pre-empt His judgment. Of course, the Church has Her command inside history: The command firstly to preach and preserve the word of truth. There is some rule of faith and order, which must be considered as a canon. Whatever exists beyond is an “abnormality”. But this “abnormality” must be healed, and not simply be condemned. This is what justifies an Orthodox person’s participation in ecumenical dialogue, with the hope that with his witness, the Truth of God makes it possible to win human beings.”37

This is the ecumenical protopresbyter George Florovsky. We consider the essay on “The Boundaries of the Church” as a product of a young Florovsky, fragmented and lacking clarity. However, he remains a theologian that contemplates, unafraid to theologize and to speak about the Church, because he feels like a son in the house of his Father, and has the freedom in Christ, with which we become fellow citizens with the saints, and of the household of God (Eph. 2:19). This freedom liberates us with the Holy Spirit, the Comforter, the Church of the Living and Philanthropos God, who became man for us men and for our salvation—and that of the entire world.

Consequently, we cannot separate the boundaries of the economy of God from the limits of the Eucharist. And thus, we cannot expand the charismatic limits beyond the canonical, nor can we restrict the canonical so much so that we exclude the practice of the Church in the reception of heretics. The moment that admission and participation in the unity of the Church is realized, meaning in the Eucharist, then we judge those who come; and moreover, not in an objective manner, otherwise we would be objectifying the Sacraments above the Church. This constitutes a paradox, a type of antinomy; yet, in the end, this is the truth.

What a beautiful precise piece so needed nowadays. We need more of Bp Athanasius' writings in English. What an inspired hierarch (who even knew St Justin Popovich personally).