Nun Theodosia (Tikhonovich) was born in Paris, raised alongside Russian emigrants, tonsured a nun in the Holy Land, and now she lives at the Kiev Caves Lavra. She literally grew up in the Church and had the privilege of associating with saintly men who remained in her heart forever. Mother Theodosia tells how St. John of Shanghai taught those under his care to be merciful to others and why the miracle of the Holy Fire cannot be explained in human terms.

—How did you, a Parisian, end up at the Kiev Caves Lavra?

—I was born in France in 1954. My mother who hailed from the Poltava region [central Ukraine] was sent to a Nazi concentration camp, but survived, so my sister and I were born in Paris. We were very poor and hungry in our childhood, and our mother was often sick. Our living conditions distressed her greatly, and so we were sent to an orphanage. However, we spent all weekends and holidays at the Convent of the Mother of God of Lesna. It is 100 kilometers (about sixty-two miles) away from Paris. Unfortunately, it is now in schism [belongs to the “Russian True Orthodox Church”—Trans.].

On graduating from school in 1970, I went on my first pilgrimage trip to the Holy Land and fell in love with Jerusalem, as many people do. Two years later I joined the Ascension Convent that was under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. After some time I met Bishop Paul, Abbot of the Kiev Caves Lavra, who baptized my relatives in Ukraine, and in 1999 I returned to my historical motherland with the help of God.

—What memories of your “monastic” childhood do you have?

—When I was a girl I once asked our Abbess Theodora, “Who was the principal saint of Kiev?” She answered, “Prince Vladimir. And why are you asking?” And I said: “Because I want to find my close relatives.” Then I was a little girl of six. The abbess replied, “Then pray at the prayer service and take Communion on his feast-day, and you will find your relatives.”

And this is precisely what happened. I found my kinsfolk in 1976, when I already was a novice in the Holy Land.

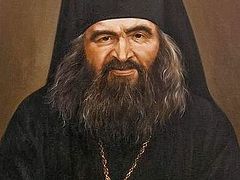

And, if I can boast about it, I am a goddaughter of St. John of Shanghai. I was born ten weeks premature and weighed 1.5 kilos (c. 52.91 ounces) and was almost dying. A week later St. John baptized me and I have considered him as my protector ever since.

—What memories of him can you share?

—The only memories I have of St. John are those of my childhood. Above all he loved orphaned children and took special care of them. St. John taught us to love prayer and be merciful towards others.

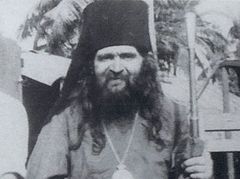

St. John of Shanghai at the grave of a former Cavalier of the Imperial Order of St. George fought with General Kornilov. The girl behind him to the right is Lena Tikhonovich, the future Nun Theodosia.

St. John of Shanghai at the grave of a former Cavalier of the Imperial Order of St. George fought with General Kornilov. The girl behind him to the right is Lena Tikhonovich, the future Nun Theodosia. For example, he would take us to a hospital with him. I remember, there were three of us little girls: Lyalya, Lelya and Lyulya. I was Lelya. There was also a boy named Philip. First the archbishop took us to a shop and said:

“Choose toys for yourselves.”

We had no toys at all at that time. We were very poor.

So he said to me:

“You, Lelya, will take two toys.”

I was a child but I already realized that a number before comma on a price tag meant “expensive”, and a number after comma on a price tag meant “cheap”. Thus I was looking at the toys very closely. Then Vladyka came up to me and said:

“Don’t look at the prices. Just select what you like.”

In my childhood I liked “furry” soft toy rabbits very much, so I chose two rabbits—a bigger one and a smaller one—and hid the latter behind my back.

Next we proceeded to a children’s hospital. On seeing St. John the babies immediately burst out crying. The fact is that his physical appearance was not attractive, he was humpbacked, with unusual hair, and he would often walk barefoot. In a word, he was like a “fool-for-Christ”. We approached one of the girls, and he said:

“Lelya, give your toy to this girl.”

But I thought to myself that I had not yet had time to play with them. So I gazed at Vladyka, and then at the girl. And St. John told me:

“This girl is now ill, and you are well. But later you will be ill, too.”

I loved Vladyka so much that I couldn’t help but obey him. So I gave the bigger rabbit to that girl, keeping the smaller one behind my back. And from that day on I had a nickname—“Rabbit”.

When we went out of the hospital, Vladyka said to my friend Lyalya:

“You will become a matushka [the Russian word that may refer to either a nun or a priest’s wife in the Orthodox environment as a rather informal and affectionate form of address—Trans.].”

But the girl shouted: “No, I don’t want to live at a convent!”

“Well, you will have to accept it. You will be a matushka,” he replied. Now she is a priest’s wife in Geneva.

This is what he said to me:

“Where you take your first steps you will take your last.”

The holy bishop used to speak figuratively, so we interpreted his words in the following way: If my first steps were at a convent, then my final steps were to be taken at a convent as well.

Only Philip refused to give his toys to sick kids pointblank. St. John and Philip were standing at the bed of a sick boy: and the both boys were crying—the sick child was afraid of the strangers, while Philip did not want to share his toy.

Later Vladyka John said to him:

“You will come to a bad end.”

And, alas, when Philip grew up he became a drug addict and died very young.

When I was eleven, the holy hierarch already served in San Francisco, and he came to Paris for the last time. During our meeting he predicted to me that I would live in Russia. I thought to myself: “Perhaps Vladyka has grown old. How can I see Russia, if I was bred in the environment of the Russian emigration that was one hundred per cent against the Soviet Union?” However, by divine providence, I ended up here.

We loved our Vladyka John dearly and were ready to follow him everywhere, although he was strict. I would hold his staff when he served at Lesna Convent, and I was not allowed to shift from one foot to another—I was supposed to stand straight. He demanded the same of others as well. We were not supposed to talk in the church. Vladyka John never omitted anything at the Liturgy, services were very long and so we sometimes grumbled mentally: “When will this service finally end?”

We were little yet we loved him beyond all measure, and we have kept this love over all these years. And I know that if I pray to him my prayer will certainly be answered. The same thing occurs with people who come to the Kiev Caves Lavra—they address their petitions to the holy fathers in the Caves, and I am sure that their prayer requests are always fulfilled.

—If he was strict, unattractive and sometimes behaved weirdly, then why was he loved so dearly?

—He knew everything. Words cannot explain it. I loved him as a child and was attached to him.

—Now you are speaking about Archbishop John’s gift of clairvoyance?

—Yes, he was clairvoyant. For example, once it was time to kiss the cross after the Liturgy. Two women were standing behind me and arguing. One of them said to another:

“I won’t come to the cross. I am fastidious and cannot kiss his hand.”

And the second lady replied:

“No, this is the archbishop! You ought to come up to him.”

But the other woman wouldn’t listen to her. So the second lady came up to Archbishop John alone, and he said to her:

“Go and tell your friend to come and kiss the cross. It is not necessary to kiss my hand.”

There is one more story, this time from my early childhood. I was young, but very stubborn. I already had a duty to place the eagle rugs [the small circular rugs on which a bishop stands during the service. They depict an eagle (symbolizing his power) hovering over a city (symbolizing his diocese)—Trans.] on the floor during hierarchal services. One day a bishop kicked an eagle rug aside, saying that he wouldn’t stand on it after Vladyka John. And I loved Vladyka John so much. So I thought to myself: “Ah well! I’ll show you!” I decided not to tell Mother Theodora anything this time. There was a meeting of the Holy Synod on the following day with five hierarchs celebrating the Liturgy. I laid eagle rugs in front of each of them but one. The abbess commanded:

“Lelya, the eagle rug!”

But I shook my head.

She repeated again: “Lelya, the eagle rug!”

But I shook my head again.

After the Liturgy everybody began to ask me: “Lelya, what is the matter? Why did you not place the eagle rug?”

At the same moment Vladyka John entered and uttered, “But maybe someone didn’t want to stand on this eagle rug?”

I was five and a half years old, and I thought: “Now Vladyka is going to give me away and tell everybody about my mischievous behavior and childish tricks.”

But before I was fully exposed I said, “Oh, I am sorry, Vladyka! I stole some cucumbers in the kitchen-garden yesterday! I had such a great temptation!”

He loved children. And that love remained in my heart forever.

—It is known that St. John healed people. Did you happen to witness such miracles?

—I remember he would often visit hospitals, take people to church and give them Communion. And if any doctors were speaking of one or another patient fatally ill, Vladyka disagreed with them, saying, “He will survive.”

When he had no time, he just found words of consolation: “Everything will be well.”

And patients recovered each time.

One woman developed cancer. She had an operation and on the third day after it the doctor came to her and said: “You have no cancer. Everything is clear.”

“What do you mean?!” she asked; she was surprised to hear that.

“I don’t know. I think your grandfather was here—he blessed you with a cross and sprinkled holy water over you.”

“I have no grandfather!” the woman argued.

“But here is his portrait, standing on your bedside-table!” the physician replied.

And it was a photograph of St. John of Shanghai.

My life is also filled with amazing miracles. If I do something wrong, Vladyka John appears to me in a dream, shakes his finger at me and says, “Beware lest your candle go out.” And I realize that I did something wrong. As a matter of fact, I don’t believe dreams, but that is a particular case.

—What was the life of the Russian diaspora like in Paris during those years?

—The Russian diaspora in Paris was spiritually very strong. All were pious Christians. I lived in an orphanage, but every Saturday and Sunday we would attend church services and we never missed them. Skipping church was unthinkable for us. Children were kept busy at services. For instance, my obedience was blowing out candles and setting the lectern in its proper place. We would confess and receive Communion regularly and I couldn’t imagine my life without all of this.

My confessor was Vladyka Laurus (Skurla). It was he who tonsured me in Jerusalem in 1986. I cannot remember him either without tears. He loved us dearly; he was a man of humility and prayer as well. And, glory be to God, it was under him that the Eucharistic communion between the ROCOR and the Patriarchate of Moscow was restored.

I knew Vladyka Laurus from the age of ten. At Lesna Convent I was charged with ringing a small bell to call everybody for dinner. I first ran up the stairs to the second floor and then, grasping the handrail, slipped down the stairs. Oh! Once I “fell” this way right into the hands of Vladyka Laurus. It was our first encounter. Later I would confess to him. He used to say to us that the most important things are prayer and humility.

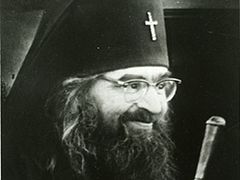

Vladyka Anthony (Bartoshevich: 1910-1993; to the left) after his consecration as Bishop of Geneva by a group of bishops presided by Archbishop John (Maximovitch) of Western Europe (to the right). Geneva,1957.

Vladyka Anthony (Bartoshevich: 1910-1993; to the left) after his consecration as Bishop of Geneva by a group of bishops presided by Archbishop John (Maximovitch) of Western Europe (to the right). Geneva,1957. —What can you say about your life in the Holy Land?

—The life there was very good, although the discipline at the Ascension Convent was very strict and we did not even receive pilgrims. I joined the convent under Abbess Tamara (nee Princess Tatiana Constantinovna of Russia: 1890-1979), who was a daughter of Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich and great-granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I. She would always go to church earlier than others and she instructed us to come to church ten minutes before the beginning of services so that we could concentrate on prayer after the everyday fuss and obediences. We would first come up to the icon of the Mother of God “Quick to Hear” and then the abbess would give a blessing to each of us. Next she would give us something to read, for example, The Philokalia or St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov), and a month later she would ask us what we thought of those books.

—You lived in Jerusalem for twenty-seven years and you had the good fortune to observe the descent of the Holy Fire many times. Nowadays there are widespread allegations that the Holy Fire is no more than a symbol, that it is not a miracle and appears in a natural manner. Can you comment on this?

—I was present at that event as many as twenty times. It cannot be explained in human terms—you can either believe or not believe and nothing else. There was one incident. Once two curious persons—I and another nun—immediately after the descent of the Holy Fire entered the rotunda after the patriarch had left. I have no idea how we managed to get inside because there were a great multitude of people. One Greek was scolding us, but we didn’t care as we didn’t understand him anyway. So, while the procession of the cross was being held, we were standing in the rotunda for some four hours. Meanwhile, the walls of the Holy Sepulcher were covered with something resembling dew. The Holy Fire is fire plus water. And it smelled so wonderful! That was simply inexplicable. In the hands of some people it even ignites of its own accord. So we can believe that it is authentic.

—Have you ever regretted leaving the Holy Land?

—No, I haven’t. Perhaps with the exception of Holy Saturday, when you think of the Holy Fire all the time. But all in all, I feel fine here. After all, how can you not love the Kiev Caves Lavra?