Only a handful of specialists now know about a liturgical rite called “the Furnace Act” practiced in Russia from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, and mentioned as early as the tenth century in Byzantium. It was a rite that was celebrated on the great feasts. With this rite also began the forefeast of the Nativity of Christ. One of the musical-folklore specialists who has researched the “Furnace Act” is Andrei Kotov, creator and conductor of the Siren Choir—a marvelous Russian choir that performs ancient Russian religious music.

“We searched a long time for it. At first we found a description of it in the Book of Rites of the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin (there are only two descriptions extant—in the Dormition Cathedrals of Moscow and Novgorod), and having found a detailed description, we started our search for the music,” recalls A. Kotov.

“It took us nine years to gather a unified Furnace Act—we had to find all the music that went into it. Of course, many music theorists helped us… Our own Polina Terentieva, who sings in our group (she is our remarkable theoretician and singer) began an intense search, and found the “demestvo four-tones”1 and some amazing music for the Furnace Act.

“The Furnace Act was part of the Matins service. It was part of the canon; the canon was read until the sixth ode, and then instead of the seventh and eighth odes of the canon came the Furnace Act.” The canon in Orthodox Church music has nine odes, or sections of song verses, which begin with an “irmos”—generally sung—and continues with the verses, which are usually chanted. In almost all canons, the seventh and eight irmoses mention the themes of the three holy youths in Babylon, Ananias, Azarias. And Misael, who refused to worship the idols of Nebuchadnezzar and were therefore cast into the “burning fiery furnace”. But the youths sang praises to the Lord and were not consumed by the flames. This is a liturgical theme that appears repeatedly, as a prefiguration of New Testament themes. A. Kotov continues, “Nine “dew verses” (that is, nine stichera) were sung, and then came the seventh and eighth “Three Youth verses” (they can be found in the Psalter separately). They were sung in the demestvo tones.” The verses of the Three Holy Youths in the furnace are part of the Biblical Odes, which at one time were sung throughout the year, but are now generally used only during Great Lent. The seventh Ode is annotated in the Psalter as “A Prayer of the Holy Three Children (Dan. 3:26–56)—the praise of the three Youths doth quench the flame. O our God and the God of our fathers, blessed art Thou.” And the eighth Ode is the annotation, “The Hymn of the Holy Three Children (Dan. 3:57–88), O praise the Lord, ye creatures which He hath made. O praise ye the Lord, ye works of His, and supremely exalt Him unto all the ages.”

A. Kotov describes how this would have looked in the cathedrals of ancient Russia:

The Furnace Act.

The Furnace Act. “In the Dormition Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, they would remove the central pannikadila ('many lamps'—basically a large church chandelier in the center of every Orthodox church), and it its place 'angels' were hung from a special block; these angels were painted by iconographers. The block was sewn from cowhide and painted by iconographers.

“A special furnace was set up. The only extant furnace is located in the reserve exhibitions of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg (not in very good condition, but at least the construction exists).

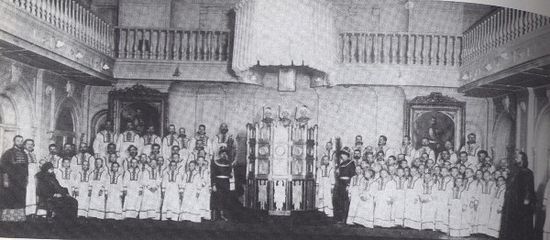

Singing the “Furnace Act”, the Kastalsky Synodal choir, 1909.

Singing the “Furnace Act”, the Kastalsky Synodal choir, 1909. “This was a large ambo (pulpit). It was of carved wood, beautiful, and painted with iconographic depictions of the Holy Forefathers of the Church, and the Holy Angels. That is, this was a great and serious event, which was prepared ahead of time. And the entire day that the Furnace Act was to be sung was dedicated to this Act.

The Children in the furnace.

The Children in the furnace. “In the morning the singers would again arrive, dress themselves in the same way, walk with the Patriarch to the cathedral, and the Matins service would begin. It would go on according to the rubrics, the canon would begin, continue to the sixth Ode, and the Furnace Act would ensue. The archdeacons together with the Youths, standing in the furnace, solemnly read the Gospel and so on. This is how this remarkable rite was served. The only thing that changed in this service was that the Gospel reading for the day came only after the Furnace Act, after the canon.

“Now anyone [who knows Church Slavonic] can find this rite and find out for himself how beautiful and interesting it is!”

The Furnace Act was hymnographically very complicated. The singers, particularly the Youths, had to be very well trained musically. Kotov talks about how his Siren Choir put together their own rendition of it:

“We did not change anything. But the Furnace Act requires a large number of singers, and precisely for this reason we very rarely perform it. We reckoned that in order to do it we would need twenty-two men! And that is only the minimum. In general, for the singing of the Furnace Act two cliroses (choir sections), three youths, two Chaldeans, and the children’s teacher [the Prophet Daniel] are needed. Two cliroses should have a minimum of eight people. And that is the minimum number, because otherwise the four-tone demestvo cannot be sung. Furthermore the three youths have to be very highly qualified singers, because this is very complicated music… Before the revolution… this was all achieved through the efforts of highly qualified choir 'guilds', which existed in the Church.”

As of this interview in 2014, the Siren choir had only performed this Act in Poland. We say, “performed”, because it was done as a concert and not as a liturgical rite. “We were so happy, because for the first time since the seventeenth century we were able to sing the Furnace Act from beginning to end, without shortening anything, and with all the readings.”

A. Kotov emphasizes that this is not a mystery play. The mystery play developed in the Western Church as an explanation for the uneducated people of the Church services, which were sung in Latin. The simple folk did not know Latin and therefore could not understand what was being taught through Church hymnography, and so dramatic enactments of the Nativity Gospel story were presented publicly. The mystery plays as such have gone into disuse since local languages began to be used in Catholic services, but one can suppose that they live on in the form of our church “Christmas plays”, usually enacted by Sunday school children. However, the Furnace Act was embedded in the Orthodox Church services for the great feasts, and was not a dramatic presentation.

“As for liturgical rites, we now know much less because very much has passed into disuse, including this rite. Fortunately the rite of the Furnace Act was described in writing. But there also existed for example a special right of the Last Judgment, and the Prodigal Son. There is also a rite that we know and that still exists to this day—the rite of the Washing of the Feet [celebrated on Great and Holy Thursday], which is one of the many ancient rites.

“We had no mystery plays in our Church. There were rites, but no mystery plays, because there was no need to explain things to people—they all heard it in their own language, especially since from the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, Church Slavonic and conversational Russian language were very similar.

“In general, this is a peculiar history in cultures that experienced specific stages in their development: First there existed the divine services, then theology, and then aesthetics. First the essence, then a delving into the essence, and only later discussion of it: Is it like this or not, can we do this, or do it differently. This is now art; it unfolds gradually. When art breaks away from the Church and becomes secular (which we now see in Europe and everywhere), it becomes very dangerous, even though at its foundation lie good intentions, such as the desire to express how we interpret the divine services, for example.

“Our [Russian] interpretation of the divine services gave birth to composers’ renditions of the service hymns, which is in my view not right, because these are two completely different things. Now people come to services and listen to how beautifully the Eucharistic canon is sung, how beautifully the Cherubic Hymn is sung…

“I once asked some music theorists with whom I worked why I can’t find an ancient Liturgy. ‘They didn’t write it down!’ was the answer. Everyone in the church sang it, because it was the same every day! And it never occurred to anyone to sing the Cherubim Hymn, for example, in this or that motif! This is because they didn’t sing—it was prayer voiced in words!

“I am often asked ‘Why was ancient hymnography so long?’ The fact is that church singers received a lesser ecclesiastical consecration. The church choir at services represented the ranks of angels; this is written into the Rubrics. The Rubrics don’t say “choir” or “cliros” but specifically “lik” [Church Slavonic for ranks, or countenances.—Trans.] So, you come from the street into the church. Out on the street you are a pained commoner, and now you have come into church, and you have become an angel! And where is it better for you to be—among the angels, or on the streets, in sickness, death, cold, and hunger? Therefore people did not rush to leave the church, because in the church is the Kingdom of Heaven. You sing, and you are like an angel. And the longer you sing, the longer you are among the angelic ranks! That is why no one was in a hurry to leave!”

Remember, that in those days everyone in the church sang the Liturgy, and so everyone was an angel. In these holy days of Christmastide, let us sing with the angels and glorify our Newborn King!