We’re eating in the trapeza of a Greek women’s monastery in honor of the Life-Giving Spring Icon of the Mother of God, located in the Sierra Nevada foothills in California. Besides the usual monastery fasting foods, there are gifts of the generous California nature on the table: olives, oranges, grapefruits. The pilgrims’ tables are some distance from the sisters’ tables; in the stillness you can hear the measured reading of the holy fathers, prayer, and the soft banging of spoons—all as usual in a monastery.

The sun shines brightly outside the window; the weather in March in these parts is about like June in central Russia. The almond blossoms are in bloom, many bright flowers adorn the monastery garden, filling the air with a sweet fragrance. All around is breathtaking mountain scenery, pure air, and the monastery’s marvelous churches with beautiful paintings on Gospel themes.

This wonderful monastery, founded by Elder Ephraim of Arizona, along with eighteen other monasteries in America, is quite far from the nearest city of Dunlap, among wild nature. Pilgrims come on weekends, so all the pilgrims’ tables, except for ours, are empty, although ours is completely full: Besides us, three Russian pilgrims, there are four bearded you men sitting behind us, their backs to the sisters. Greeks? Americans? We didn’t have to guess for long: After the meal they came up to us and introduced themselves, and we were glad to meet our compatriots—Russian iconographers, working on the iconography in the monastery cathedral.

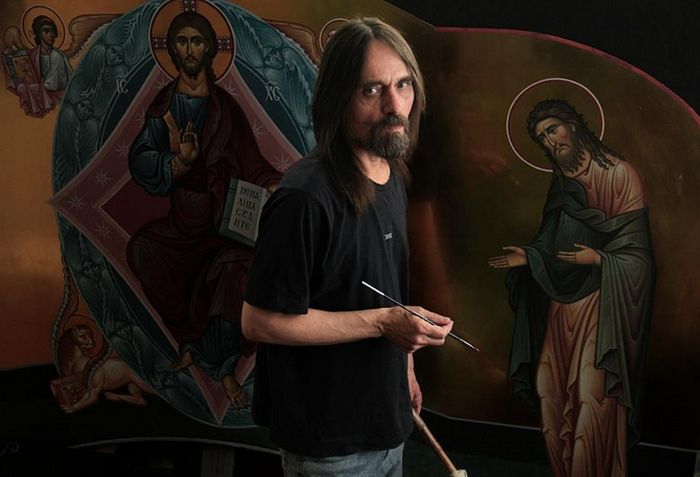

They are members of the Artists’ Union of Russia and teachers from the graphic arts department of Kuban State University: associate professor of painting and composition Maxim Odaryaev and associate professor of graphics Ivan Storchak, and also the iconographers and artists Roman Martinenko and Irakly Karulashvili. Like us, they are staying near the monastery, at St. Nicholas Ranch. It’s a Greek Orthodox conference center and place of rest for the Orthodox. They also hold youth camps,various events, and accommodate pilgrims there.

Our new friends told us about themselves and their work.

“We were doubters, but we became believers”

We graduated from Kuban State University and defended our dissertations at Moscow State Pedagogical University. We were young artists, far from faith and from the Church, but, apparently the Lord was already thinking about us. In 2002, we were invited to paint the St. Elias Church in Krasnodar.

The St. Elias Church has an interesting and tragic history. In 1892, a cholera epidemic raged in Kuban for nearly half a year, killing more than 15,000 people. Then the people turned to the prophet Elias for his prayerful help, a moleben for the blessing of water was served in Ekaterinodar, and the city residents promised to build a church in honor of the great saint in case of deliverance from the epidemic.

By the intercessions of the holy prophet, Kuban was delivered from danger, and the people began to gather donations for construction.

The beautiful church, built according to their vow, was closed during the years of persecution against the Church, was opened again during World War Two, but was turned into a warehouse in 1963.

We painted this ancient church for four years under the guidance of the famous artist and iconographer Vyacheslav Tolmachev. As a master, he made a turn from avant-garde to spiritual painting, continuing the tradition of the Byzantine and Russian schools. In the 1980s, he painted the Krasnodar cathedral, which was very difficult to do at that time: The Soviet authorities put up impediments. The iconographers had to jump through a lot of hoops, because the First Secretary of the city council was taken aback by the words “painting a church.” They had to document the painting of the cathedral as the “restoration of a monument of cultural heritage.” Vyacheslav was basically living in a shed at the church then.

Tolmachev became a mentor for us, and in many ways influenced our choice of path in life and our development as painters. He had many serious difficulties in his life that he was able to overcome thanks to his faith. It was very interesting for us to speak with him: There are many artists around, but such large-scale personalities like him, such talented people in iconography and in monumental iconography we have not met. He was a holistic personality, ascetic and demanding of himself, and strict, in a good sense, towards his students.

Commencing this work, we immediately realized that what we learned in university was not enough. Icons have an entirely different space. There were many who tried to take part in painting the St. Elias Church, but over time, only a skeleton crew remained.

Archpriest Sergei Ovchinnikov, the rector of this church, a military priest of the Kuban Cossack army, also had a great influence upon us. That’s when we confessed for the first time in our lives.

After four years of working on painting the church, we not only learned a lot about iconography, but this work changed us entirely: We were doubters, but we became believers.

In the mountain monastery

After working in the St. Elias Church, we painted a chapel of the holy Great Martyr Demetrios of Thessaloniki, and other churches, and then we studied in graduate school, defended our dissertations, and started teaching.

We came to New York to give a master class at a company that deals with interior design. We led the master class and were already getting ready to leave when we suddenly got an idea: It would be good to paint an Orthodox church here, in America. And the very next day the Lord sent us someone with whose help we immediately received two proposals for painting churches—one in New Jersey, the other in this monastery of the Life-Giving Spring.

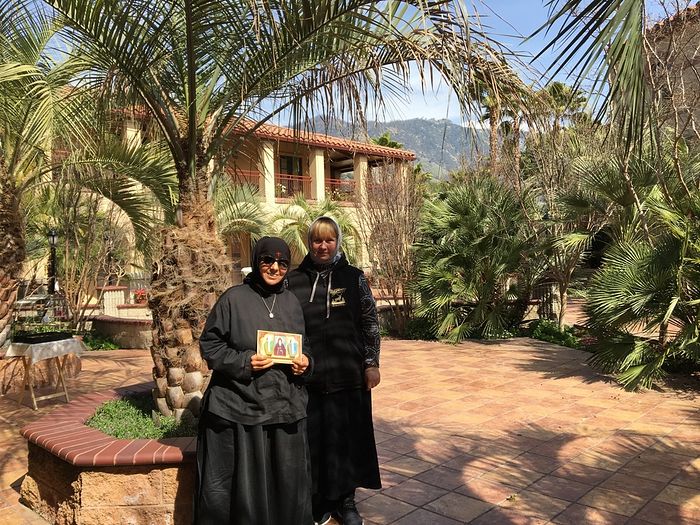

The abbess of the monastery, Mother Markella, was choosing the artists for painting the monastery complex. We joined in the competition and didn’t know if we would suit because there were other applicants. In the end, we won the competition, and we’ve been working here for a year already, doing the wall paintings in the largest monastery in California in a Byzantine-Russian style, in accordance with the canons of Orthodox iconography.

It’s very interesting work and a completely different environment. The monastery has a rich library, with very rare books on fresco painting. Literature of this kind is almost inaccessible—it has a very small circulation.

The monastery also has its own good iconography workshop; the sisters paint icons, and we talk with them, influencing each other. We admire the nuns and their ascetic way of life: They only sleep a few hours every day and they still manage to do quality work, participate in the services, and pray a lot.

We also go to the services and work a lot—eight or nine hours a day. Here, in this mountain monastery, far from human commotion, you find a special, peaceful state; you enter into a spiritual, prayerful rhythm, and you remain there. The parishioners of the monastery are very welcoming. Pilgrims and the faithful—it’s like we’re here in a spiritual reserve.

And in terms of the environment, it’s like we’re in a true reserve: The nature all around is untouched by civilization, and many wild animals live here. Yesterday, when we finished work and went to relax, the matushka of the serving priest caught up to us and warned us not to go on foot in the evening because mountain lions had begun to attack.

Deer often come to our yard. One evening we were coming from work, it was already dark, we were caught up in conversation, and then we looked, and we were surrounded by deer.

Purity and love can be felt in the abbess of the monastery Mother Markella; there’s grace coming from her. The sisters take care of us, and we feel their motherly affection. There’s flowers all around—it’s obvious that it’s a monastery of the Most Holy Theotokos. It corresponds exactly to its name—“Life-Giving Spring”—beginning with Gerontissa and the sisters, and ending with everything that surrounds the monastery.

There are many temptations when you’re living in the world, but here your thoughts are purified simply because you’re among prayerful women, under their prayerful protection. All that’s superfluous leaves, and you realize it was superfluous.

***

We wished the Russian artists God’s help in their work, and they asked us to convey their bow to all the readers of OrthoChristian.com. They also wished that you would make sure to go from time to time on pilgrimages to monasteries—spiritual hospitals and spiritual reserves for the faithful!