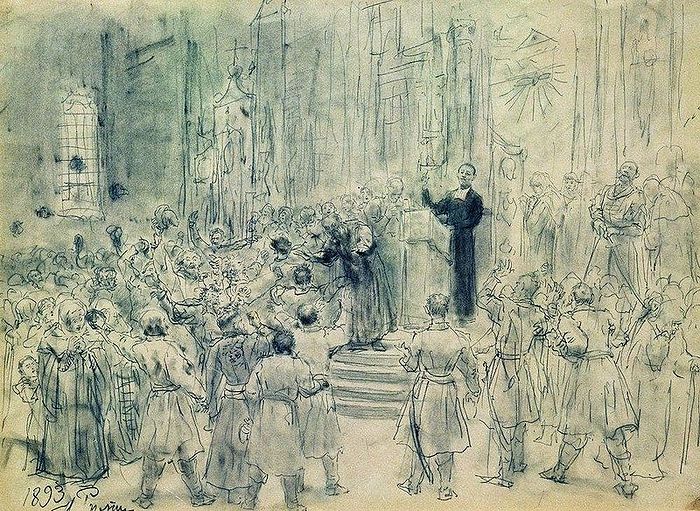

Artist Ilya Repin: Sermon of Josaphat Kuntsevich in Belarus. Graphite on paper. Photo: Wikipedia. Jesuit priest Joasaph Kuntsevich was the main proponent of the Unia of Brest, Belarus, and its harshest enforcer.

Artist Ilya Repin: Sermon of Josaphat Kuntsevich in Belarus. Graphite on paper. Photo: Wikipedia. Jesuit priest Joasaph Kuntsevich was the main proponent of the Unia of Brest, Belarus, and its harshest enforcer.

Amidst the ever-unfolding confusion about Orthodoxy in the Ukraine, this Ukrainian author from the Union of Orthodox Journalists website offers a little history that goes a long way in explaining the status of the canonical Orthodox Church in Ukraine.

There was no other way out. We were besieged by the Uniates.

The History of the Russian Church, as well as that of the Kievan Metropolia, separated between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, can be characterized mainly in the light of

- The weakness at the center of the Patriarchate of Constantinople

- The strong influence of Catholicism on the Ukrainian lands controlled by Poland [The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.—Trans.]

The autocephaly of the Russian Orthodoxy Church—which was formerly a part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate from which Kievan Rus’ was baptized in 988—was proclaimed against the backdrop of the signing of the Ferrara-Florentine Union[1], by Constantinople and other Eastern Patriarchates.

This politically motivated Union was an attempt to unite the forces of East and West in the face of the Turkish threat. It clearly showed the general position of Orthodoxy in the East, and the weakened position of the influence of its jurisdictions.

The Orthodox Patriarchates of that time were held hostage by Islamic secular power, and as a result, the dependent territories also inevitably had to experience all the possible consequences of Church geopolitics.

The Muscovite state, which for a number of reasons was the least of all threatened by Turkish expansionism, found itself in an unusual position.

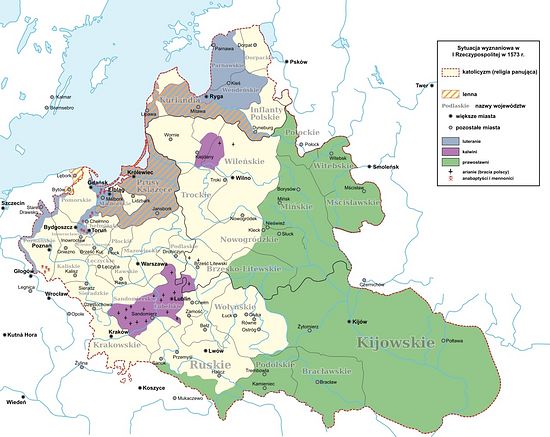

Religions in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1573 (Catholics in yellow, Orthodox in green, Protestant in purple/gray). Photo: Wikipedia.

Religions in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1573 (Catholics in yellow, Orthodox in green, Protestant in purple/gray). Photo: Wikipedia.

While on the one side, the threat of Islamic intervention in Muscovy was by far smaller than, say, in Hungary or Wallachia, on the other hand, the Russian Church would still have been forced to accept the Ferrara-Florentine Union, becoming a victim of the geopolitical realities to which the Muscovite state was not party.

The period when the Ecumenical Patriarchate held jurisdiction over the Kievan metropolia of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries is considered by many domestic historians to be a period of Constantinople’s nominal authority.

On the one hand, this allowed the Kievan metropolia to be essentially self-governing; however on the other hand, this made it vulnerable to the very forceful policy of Catholicization[2] that was being actively pursued by Warsaw.

The turning point for Orthodoxy coincided with the awakening of national self-consciousness among the Orthodox population of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth [Polish: Rzeczpospolita]. In 1648, when King Jan II Casimir (Vasa) ascended the Polish-Lithuanian throne, he resolved not to admit a single non-Catholic to a leading post in the entire Commonwealth.

Even the Hadiach treaty of 1658, which was signed to protect Orthodoxy in Poland after an acute period of conflict, was set aside in favor of Uniatism.

After the abdication of Jan Casimir from the throne in 1668, the general Polish confederation passed a law whereby “apostates from Catholicism and Uniatism” (i.e. Orthodox people) were deprived of civil rights and freedoms, and were subject to exile.

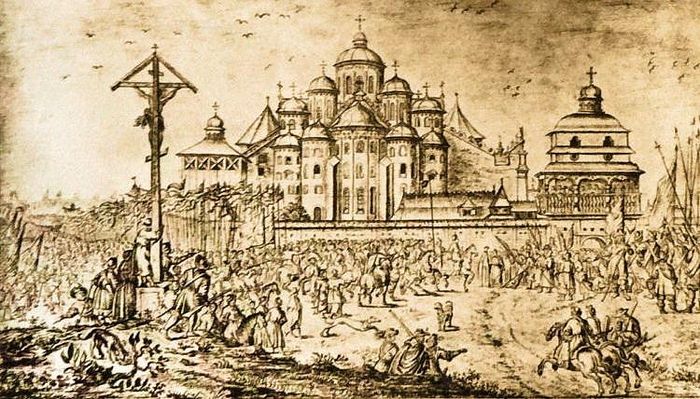

Rzeczpospolita--The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Rzeczpospolita--The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In Church relations, the situation was no better. The Cathedræ[3] in outposts of Orthodoxy in Western Ukraine, such as the Lviv and Lutsk dioceses, were often purchased by bishops for money under one main condition—loyalty to the Unia. Orthodox Churches were seized en masse by the Uniates. At the same time, this violence over freedom of religious confession in Poland was strengthened at the legislative level, and as a result, the Orthodox population of the Commonwealth had no defense in the courts of law.

The defenseless position of Constantinople, together with the deteriorating state of the Orthodox people in Western Rus’, in the end lead to the Russian State sending their own representatives here [to Modern-day Ukraine/Western Rus’.—Trans.] to protect the rights of Orthodox believers. Nominally, Western Rus’ was then still a part of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The Polish King in principle did not acknowledge the Patriarch of Constantinople, a clear indication of this being a 1676 declaration of the Sejm [Polish parliament.—Trans.] made ten years before the change of jurisdiction, forbidding Orthodox Ukrainian Brotherhoods and local hierarchs to have any communication with the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Mother Church could then do nothing about it, even as it already couldn’t do anything in principle, being as it was a hostage of the Ottoman Empire.

Moreover, even fifty years before the events described, nothing prevented the Polish authorities, for example, from declaring the assistant of the Ecumenical Patriarch—Patriarch Theophan of Antioch—as an impostor, and with stroke of a pen, they declared all of the bishops whom he consecrated in Western Rus’ non-canonical.

Beyond sending notes of protest, written assurances, and exhortations for the faithful to preserve Orthodoxy, the Ecumenical Patriarchate did nothing concrete.

Caught between the powerful Catholic West, and the powerless Greek East, the Western Russian Church could only proceed down the path of the restoration of historical justice: to restore the unity of the divided Russian Church, and to enlist the support of the Patriarch of Moscow as well as the Russian tsar to restore not simply a nominal, but a real Church and secular authority.

It would not be superflous to add that the division of the Metropolia in 1458 was, in particular, the handywork of Pope Callixtus III, who perceived the Kievan Church as consisting of two parts: “Upper Russia” and “Lower Russia”. Thus we can see that what once lead to the separation of the Church, now, on the contrary, contributed to its reunification.

The exact moment and circumstances of the transfer of the Kievan metropolia to the Moscow Patriarchate is to this day the subject of speculation, which supposedly boils down to the nuances of the translation of the Patriarchal letter. There are a large number of studies on this subject, supported by an analysis of the original text of the letter of Patriarch Dionysius; but, given the special character of Greek Church diplomacy, it is extremely difficult to put an end to this complex issue.

Firstly, there is no clear timeframe. In other words, the original letter gives the Patriarchate of Moscow the right to consecrate and appoint the Kievan Metropolitan, but it says nothing about any timeframe ascribed to this right. From that time on, the Metropolitan of Kiev has recognized the Patriarch of Moscow as a father.

Secondly, the single connection between Constantinople and Kiev was stipulated only at a liturgical level: The Kievan Metropolitan had to commemorate the name of the Ecumenical Patriarch first during the Liturgy, and only then the Patriarch of Moscow.

The most successful antipode of this intricate church diplomacy, and the key to understanding the “Ukrainian Church Question”, may be the tomos of autocephaly… of the Church of Greece. The fact is that decisions of the Ecumenical Throne on the autocephaly or the autonomy of a particular territory depends upon how important that territory is to them. The Autocephalous Church of Greece consists of eighty-one dioceses, thirty of which are the so-called “New Territories”.

The peculiarity is that the New Territories, (Northern Greece), are part of the Church of Greece, but in the tomos of autocephaly, it is stipulated that they were transferred from Constantinople to Athens “for a time".

In the letter of Patriarch Dionysius IV, there is no indication of a timeframe or a concrete date. It seems that the Kievan Metropolia was not so important for Constantinople, since they didn’t leave a way out for themselves. Even if Patriarch Dionysius theoretically had in mind a temporary nature of rule by the Moscow Patriarchate, then he would have not hesitated to claim his rights at the earliest opportunity.

However, neither during the liquidation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, nor during the Russo-Turkish Wars, nor after the February revolution right up to 1923 (the tomos of autocephaly of the Polish Orthodox Church), we do not see any documents of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in which he claims his rights to these territories.

Moreover, during the dreadful times of Bolshevik persecution of Orthodoxy, Constantinople never declared itself the “power-holder”. The Ecumenical Throne seems to have completely passed by the execution of bishops, priests, and laity in the USSR. As for the commemoration of the Patriarch of Constantinople first—seeing that this patriarchal grammota the Patriarch of Moscow is called, “Elder and Primate”, this can more likely be interpreted as a tribute to history.

Thus, Constantinople wanted to remain in the life of the Kiev Metropolia as a symbolic and spiritual leader. Something similar happened with some Orthodox Autocephalous Churches. Few people know, that not all Autocephalous Churches have the right to produce their own Chrism![4]

Thus, the Greek Orthodox Church mentioned above, as well as the Albanian Orthodox Church receive their Chrism from Constantinople. At the same time, both Churches are independent in their government, they have their own synods, and they themselves elect their own primate.

This system is somewhat reminiscent of the role of the British Monarch in the life of Canada and Australia. Both states are independent, they have their own currency and army, but the formal head of state of these states independent from Great Britain is still the British Monarch.

Thus, the Ecumenical Patriarch is a very special person for Orthodoxy in the lands of the former Kievan Rus’, since Rus’ was baptized by the Greeks, but he does not possess real authority here.

Symbolism and reality should not be confused, because if we were to be guided by such erroneous logic, all the Balkan Orthodox Churches would then be interpreted as only symbolically autocephalic after receiving autocephaly from the Ecumenical Patriarchate.