The 1686 tomos concerning the transfer of the Kievan Metropolia from the Church of Constantinople to the Moscow Patriarchate and the circumstances of this transfer have recently become the subject of heightened discussion. The Patriarchate of Constantinople has now suddenly begun to categorically challenge the validity of this transfer. As to just how true these claims are, and about the issues of the 1686 transfer, we spoke with a professor of St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University and Doctor of Church History, Vladislav Igorevich Petrushko.

—Please speak as to how long the Kievan Metropolia was included in the fold of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. And how long did it exist separately from the Muscovite Metropolia?

—The Kievan Metropolia was included in the lists of metropolias of the Constantinople Patriarchate from the end of the tenth century. With the passage of time, the Metropolia, remaining “Kievan” by title, was then, factually speaking, as we know, moved to the city of Vladimir.1

Kiev remained the first-throne cathedra, but only nominally.2 At the beginning of September, Patriarch Bartholomew was either deliberately or accidently making a major error when he stated that the Metropolia of Kiev was transferred to Moscow without the permission of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.3

First, it was not the Metropolia that was moved, but the Metropolitan moved, and the Cathedra remained in Kiev. Secondly, the Cathedra eventually moved not to Moscow, but to Vladimir. Vladimir was recognized in the middle of the fourteenth century by the decision of the Council of Bishops of the Church of Constantinople, as the second thronal city, and the location and seat of the Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus’.

However, Metropolitan [Saint] Alexis, with whom the decision on the transfer of the Metropolia had been made, had already moved to Moscow. The recognition of Vladimir, and not Moscow, as the second cathedral city of the Rus’ Metropolitans was associated with the reluctance to irritate the Lithuanian Prince Algirdas, who at that time entered into a fierce rivalry with the Muscovite princes.

Furthermore, as we know, in 1439, the Florentine Union was struck. During a council in 1441, in Moscow, the Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus’, Isidore, a Greek, was deposed by the Rus’ bishops and condemned as a heretic, because he had concluded a union [with Rome] and renounced Orthodoxy.

In connection with this, the Orthodox Church in Rus’ passed into its independence from Uniate Constantinople existence, inasmuch as this was a dogmatic issue, and not just a canonical one. Soon after the Moscow Council of 1441, the Eastern Patriarchs also renounced the union.

And Constantinople did so only in 1453, only after the capture of the capital of the empire by the Turks. So, the Uniatism of the Constantinople patriarchs was the reason that the Russian Church passed into autocephaly—for the sake of the preservation of Orthodoxy! The Russian Church could not obey a Uniate Patriarch!

With the election of the Holy Hierarch Jonah to the Russian Metropolia, and his recognition as Metropolitan in Western Rus’4, the entire Rus’ Church became autocephalous. But in 1458, the King of Poland and Grand Prince of Lithuania Casimir IV Jagiellon, who had previously recognized Metropolitan Jonah as the primate of the united Rus’ Church, denied that recognition and accepted instead the Uniate Metropolitan Gregory [the Bulgarian].

In Italy, Gregory Mammas5, the Uniate Constantinople Patriarch in exile, “placed” Metropolitan Gregory the Bulgarian as Metropolitan of Western Rus’. The Uniate Metropolitan Gregory was then sent to Western Rus’.

As a result, there was a division of the previously united Rus’ Church into Muscovite and Kievan Metropolias—precisely because of the forceful captivation of the Western Russian portion into the Unia.

However the Uniate Metropolitan Gregory soon saw that the Orthodox population of Western Rus’ did not accept the Unia. And Gregory, evidently realizing that as a Uniate, he cannot realize himself among the Orthodox Rusians of Lithuania and Poland, went into contact with the Constantinople Patriarchate.

He renounced the Unia, and was again received into communion, and reestablished by Constantinople as the Metropolitan of Kiev and All Russia, with a claim to the Muscovite part of the Rus’ Church. The sincerity of his return to Orthodoxy, however, was not believed in Moscow, and the prospect of returning under the strict jurisdiction of the Constantinople Patriarchate, which was now placed by, and totally dependent on the Muslim Sultan, was certainly not endearing to the Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan III the Great6, as well as the hierarchy of the Russian Church.

And in the end, this division was made solid: From that time, there existed the separate Kievan and Muscovite portions of the once united Rus’ Church.

They existed in this form until the end of the seventeenth century, when in the 80s of that century, under Patriarch Joachim (Savyolov), the reunification of the Kievan Metropolia with the Patriarchate of Moscow took place.7

—This is to say that this separation lasted about 200 years?

—Even longer.8

The Patriarchs of Constantinople did not exert influence on the ecclesiastical life of Western Rus’

First, despite the claims of the Patriarchs of Constantinople to control the life of the Russian Church, they in general did not participate in it at all. Already by the end of the fifteenth century, they renounced the originally stated demand that the Metropolitan of Kiev be sent forth from Istanbul.

At first, they sent exarchs for this, but later, this also ceased. The Kievan Metropolia, factually speaking, became self-headed (if not taking into account the ever-increasing dependence on the Polish-Lithuanian catholic authorities), only being listed as being subordinate to Constantinople.

But this independence was not a status for which the Kievan Metropolia specifically and consciously fought. It formed quite spontaneously, because the Patriarchs of Constantinople practically had no opportunity to exert influence on the ecclesiastical life of Western Rus’.

—But all the same, was the division into the Kievan and Muscovite Metropolias lived through strenuously? Was there, for example, a movement towards reunification from the side of the clerics themselves?

Ecclesiastical life in the Muscovite and Lithuanian Principalities was very divided, especially in the Polish part of Rus’: Galicia. The confrontations between the sovereigns of Lithuania and Moscow led to these ties being increasingly weakened.

And then, in the midst of it, in the second half of the sixteenth century, the Kiev Metropolia entered a very deep crisis. In many respects, it was the consequence of the right of patronage, in which persons originated from the ranks of Orthodox feudal lords and completely unfit to serve became hierarchs.

We know from surviving historical documents what ugly things were then worked by the quasi-Orthodox bishops of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Since the king did not have a special land fund, from which he could favor his subjects, and was in general a rather weak figure9, he found a way to use Church property for this purpose.

The Polish-Lithuanian monarch would encourage the Orthodox nobility with a Church land fund. As a reward for service, the King gave appointments to high Church offices—to episcopal cathedras and abbatial positions in monasteries. That is to say, the king usurped for himself the right to appoint bishops, archimandrites, and abbots. In fact, cathedras and monasteries were given for the feeding of secular feudal lords.

—But it was necessary to be an unmarried man to hold those positions!

Such a status is of course, implied. But very soon they simply stopped paying attention to it. For example, Lviv brothers complained to Patriarch Jeremias II on the eve of the conclusion of the Union of Brest, that a number of hierarchs were with their wives … or rather … their mistresses.

Hence it was an extremely deep personnel crisis, because corrupt hierarchs did not care about the Church. Not only that—some stained the Church with their actions. For example, Kirill Tarletsky, one of the signatories of the Union of Brest, was involved in some criminal cases including highway robberies, raids on neighboring estates, and rape. There was no way to put a stigma on many hierarchs of that time.

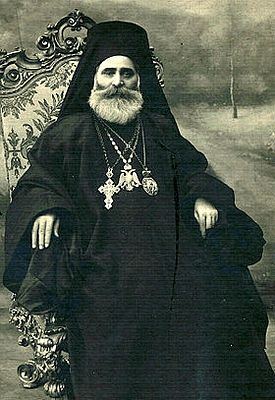

Actually, the Union of Brest [1595-1596] was conducted, by in large, because those hierarchs were scared for the first time in a hundred years, when Patriarch Jeremias II of Constantinople came to the commonwealth to restore order [a few years prior to the Union.—Trans]. They, first of all, were afraid that they could be deposed, which meant that they would lose their holdings and privileges. And it’s true, some were deposed—for bigamy, like Metropolitan Onesiphorus Divochka, and some for the unrepentant sin of murder, like the Archimandrite of Supraśl Monastery Timothy Zloba, and others.

But in all, this was just a coincidental act. Patriarch Jeremias II rode to Moscow for alms, where he participated in the enthronement of the first Patriarch of Moscow, Job. Then, on his way back, he took up administration in the Kiev Metropolia at the request of the brothers, who told him that the local hierarchs were very unseemly. But Jeremias did not know the language, and did not orient himself within the realities of the ecclesiastical life of Western Rus’. Therefore, he made rather feverish and often not very appropriate decisions.

The feudalist bishops of Western Rus’, however, were frightened that the Patriarchs of Constantinople would pave the way to Moscow, go here and there for alms, and periodically agitate and depose the Orthodox hierarchs of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Something had to be done urgently. The idea [of the Union of Brest] was first put forth by the Jesuits—the project of a new union with Rome was explicitly mentioned in the journals of the Jesuit Piotr Skarga.

The idea was to bow to the Pope of Rome and propose to him a union, in the hopes that the Bishops of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would forever be spared from the Sword of Damocles10, and that their rights and holdings would be guaranteed for the rest of their lives. Such were the realities of ecclesiastical life; but the case with Jeremias was unique.

In all, the Kiev Metropolia, after the Union of Brest and for the entirety of the seventeenth century, existed without any participation from Constantinople in its life.

This, in fact, was the main reason why the Cossacks and the clergy of the Left-Bank portion of Ukraine11 advocated the transition to Moscow’s jurisdiction.

This desire was supported by the Archbishop of Chernigov Lazar (Baranovich), the Archimandrite of Kiev Caves Lavra Innocent (Gizel), and many other Church leaders. But the problem was that the dioceses of the Kievan Metropolia, on the territory of Left-Bank Ukraine, were located in Kiev and Chernigov (restored after a long lapse by Hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky).

And the rest of the dioceses were on the territory of Right Bank Ukraine, and the bishops that were there were mostly Szlachta [Polish Nobility.—Trans.], subjects of the Polish king who were loyal to him, and were under his influence.

Nevertheless, the new elections of the Metropolitan of Kiev at the end of the seventeenth century took place with the active participation of the Cossacks, whose Starshina [leaders] in fact replaced the Szlachta.

And it is known that Hetman12 Ivan Samoilovich actively labored for the transfer of the Kievan Metropolia to the Moscow Patriarchate; therefore it cannot be said that there was any pressure form Moscow, though of course, in Moscow, Patriarch Joachim and the administration of Tsarevna Sophia also desired this.

For or Against?

—But opponents say, that at the council that elected the “Pro-Moscow” Kievan Metropolitan in 1685, mainly laypeople participated, and among the clergy there were only participants from the Kievan Diocese. They also say that prior to the tomos of 1686, Kievan clergy resisted the transfer to the Moscow Patriarchate for over 30 years.

It was not only lay people who participated in the council, but in reality there were no bishops, because the Right-Bank bishops simply did not want to participate, and the only other Left-Bank Hierarch—Archbishop Lazar of Chernigov—was greatly afflicted and insulted.

Hetman Samoilovich very much wanted to marry his daughter to the nephew of Bishop Gideon—who would eventually be elected Metropolitan of Kiev—in order to become a true aristocrat, because Gideon in the secular world was a Prince of the Sviatopolk-Chetvertynsky (Czetwertyński) family.

Samoilovich really wanted to arrange this marriage, so for him, Gideon was the preferred figure. And Archbishop Lazar, who was quite pro-Moscow himself, was effectively removed from the elections, simply for the fact that Samoilovich wanted the Metropolia to go to Gideon. Archbishop Lazar was not even invited to the council, and was therefore very offended.

Previously, he had repeatedly appointed the Locum Tenens of the Kievan Metropolia during times when there was no metropolitan, or when the metropolitan had fled to Poland—for example Dionysius (Baloban).

However, to say that the Kievan Metroplia and the Kievan clergy as a whole were against joining the Moscow Patriarchate is a massive exaggeration. Many people were in favor of it, because they saw this as a guarantee of the normalization of Church life after the long years that are called (in historical terms) “The Ruin.”

—Who among them was the larger group—the supporters of joining the Moscow Patriarchate, or the opponents?

This is hard to say, because opinions often changed. For example, take what happened when the Muscovite authorities replaced Archbishop Lazar (Branovich) with the former Archpriest of Nezhin Methodius (Maxim) Filimonov because he was more strongly associated with the Cossacks, and more known in the circles of Cossack Starshina.

But after becoming Bishop of Mstislav, Methodius—a very ambitious man—turned from a supporter of Moscow to its opponent when the issue arose of the election of the new Metropolitan of Kiev, which meant for Methodius that he would lose his status as Locum Tenens. And that meant that he, for his own interests, propagandized the Kievan clergy against Moscow. But this was a very short moment, an impulse; and when Methodius’s fears passed, the Kievan clergymen changed their position.

This entire period—from after Hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky, to Hetman Samoilovich—historians call “The Ruin.” It was the endless bowing back and forth of Cossack officers between Moscow and Warsaw. Why is this?

Cossacks mostly arose from the bottom ranks. Being that they were new risers to power, they wanted to receive the same rights as the Szlachta had before. Therefore, on the one hand, they defended Little Russia (Ukraine) from the Poles, thanks to Moscow, but on the other hand, ran to the [Polish] king to bargain: “We will return under your scepter, but only with rights of autonomy, and of course, with the condition that we will become Szlachta, receive the right to be deputies in the Sejm [Parliament], with charters of nobility, coats of arms, and so forth.”

But no one in Poland especially wanted to take them in this capacity, and so from here, we see all of this running back and forth.

And the Kievan clergy in the form of their most educated representatives were essentially “in favor” because it was obvious that under the Muscovite authorities, there would be tranquility of Church life, and most importantly—the Union of Brest would be guaranteed to be liquidated. In Left Bank Ukraine, there was nothing left of the Unia after the reunification13. Therefore this was also an important point.

Certainly, the clergy of the Kievan Metropolia also wanted some rights, preservation of autonomy, and all this was stipulated before entering the Moscow Patriarchate. And it must be said that as long as the Patriarchate existed in Russia, the special rights of the Kievan Metropolia stipulated during its reunification with the Moscow Patriarchate were respected. The fact that they were later violated was not the fault of the Russian Church but of the autocracy, which, after the synodical reform,14 established that everything within Great Russia and Little Russia be under the same order and system, and everything in ecclesiastical life was brought down to a common denominator.

At the same time, it should be noted that Peter the Great was very fond of Little Russian hierarchs, and demanded that all the bishops in Great Russian dioceses should come from Little Russia. He considered them to be more educated, more loyal to his reforms and to him personally.

Therefore, right up to the time of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, almost all the bishops in Russia were Little Russians.15 Now people forget about this, but Little Russians were not at all oppressed or unappreciated—not in the Russian Empire nor in the Russian Church. They were an essential part of it—both among the clergy and the nobility.

Therefore all this talk about a Russian colonial game in Ukraine is nonsense and stupidity. Ukraine was a part of the Metropolia; moreover, an active, and in many ways even a privileged part.

Excuses for the Affronts

—Yet still, as I understand it, the process of the reunification of the Kievan Metropolia with the Moscow Patriarchate was not entirely smooth. What circumstances does the Patriarchate of Constantinople give today as its reason for challenging the reunion?

—First of all, they speak about the pressure that was exerted on the Patriarch of Constantinople Dionysius, and the Patriarch of Jerusalem Dositheus. The latter was also one of the participants of this process, due to his great authority in the Greek community of the Ottoman Empire. They were at first opposed to the transfer of the Kievan Metropolia, but under pressure from the Ottoman authorities they eventually agreed.

Indeed, pressure was exerted, because it was important to the Turks, not to allow Russia to participate in the anti-Ottoman Coalition16. Western European countries drew Russia into this alliance, and the Turks really did not want Moscow to enter the war.

Therefore, to go to such a complete trifle, as to support the transfer of the Kievan Metropolia to the Patriarchate of Moscow was nothing to the Turks. Moreover the Kievan Metropolia was not located on their territory. In a way, the Ottomans pressured the Patriarch of Constantinople.

At the same time, it should be remembered that the Patriarch of Constantinople was “millet-bashi” or ethnarch—the leader of the entire Christian community of the Ottoman Empire; moreover, both its privileged parts—the Greeks—and also the rayah (flock/subjects), that is to say the Slavs and the other Orthodox peoples, in relation to whom the Phanarites have never held themselves as fraternal.

But the Patriarchs of Constantinople themselves completely depended on the Ottoman authorities. Most of them were replaced on their seats three or four times. None of the Greeks are embarrassed that today, at the whim of the Turkish authorities, the Patriarch could be changed, replaced with another, and then be put back the day after tomorrow—and this could go on forever.

Although it must be said that in Istanbul, the Greeks did not live poorly under the Ottoman regime. It’s another affair that the Turks always tried to make the Greeks fight among themselves, and it was very often that the replacement of a patriarch was caused by the initiative of some disgruntled Greek party.

The Turks not only fueled conflict among the Greeks, but this also served their utilitarian goals, as each new Patriarch had to pay a large bribe each time.

The second objection is that opponents [of the union with Moscow] constantly say that they claim the transfer to Moscow was with a “special right”. That is to say, that the Patriarch of Moscow would install the Metropolitan of Kiev; but they claim that he is not the first hierarch from the position of the Kievan Metropolitan, inasmuch as [the Kievan Metropolitan] is only an “exarch” of the Constantinople Patriarch.

The fact is, however, that many different letters by Dionisius and Dositheus on this subject have been preserved. And each time they used different formulations—the Greeks in general are masters at formulating language that it can be interpreted in many ways. But in many texts, the speech directly relating to the transfer of the Kievan Metropolia to be under the authority of the Moscow Patriarchate speaks of it being “forever” [for a permanent time], and without an indication of a temporary nature [“for a season/time].

Constantinople Changes the Strategy

—As I understand it, one more objection is that the very first installment of the Kievan Metropolitan, Gideon (Prince of Svyatopolk-Chetvertinsky), by the Patriarch of Moscow occurred in 1685—before the official transfer of the Kievan Metropolia to the Moscow Patriarchate. Was this, generally speaking, prior to the transfer and in violation of canonical rules, and therefore what that caused the Greeks’ resentment?

—To some extent, yes, but any insults to the Greeks at that time were easily smoothed out by gifts of Muscovite sable and gold, which is why there were so many letters about this. For each letter they asked in return for a “gold pen”. So I would not exaggerate the scale of the offense, especially seeing as the Patriarchs of Constantinople, with the exception of Jeremias II, never really dealt with the affairs of the Kievan Metropolia. It was a matter of indifference to them, and existed in general by itself. The Patriarchs of Constantinople never once indicated their position on all the problems that arose here in the seventeenth century.

—What kind of problems?

—First of all, the problem connected with the reunification of Ukraine to the Russian Tsardom. And before that—the imposition of the Union of Brest by the Polish Authorities, and the constant violation of the rights of Orthodox people in the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the time of Patriarch Jeremias II, Constantinople gave practically no support to the Orthodox people—not even moral support.

Moreover, to please Turkish authorities, who in the second half of the seventeenth century had captured Podolia from the Poles and occupied it, Constantinople took the Podolian territory away from the Metropolitans of Kiev, and formed from it a separate Metropolia. Of course, the Phanar did all this without asking the opinion of the Little Russian clergy.

The main point is that later, up until the beginning of the 1920s, the Patriarchs of Constantinople did not even try to challenge the legitimacy of the transfer of the Kievan Metropolia to the jurisdiction of Moscow. This is because the Greeks were given very much from the Russian Empire.

And none of them wanted to spoil relations with the Emperor, because only due to his support did the Eastern Patriarchates even exist. However, with the disappearance of the Russian Empire, and the beginning of the persecution of the Russian Church after the 1917 revolution, Constantinople completely changed its strategy.

Firstly, it actively began to demand that the entire Orthodox diaspora be under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, so that throughout the entire world, in places where there are no Local Churches, the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate would be recognized. This requirement was based on a very arbitrary interpretation of the 28th canon of the Fourth Ecumenical Council, which, indeed, added to the Patriarchate of Constantinople a number of provinces that were adjacent to the territory of Constantinople. But who said that this applied to the entire world, and when?

Secondly, Constantinople immediately began to take maximum benefits from the extremely difficult situation of the Russian Church at that time. For example, he took the Orthodox Church of Finland (a country that had just achieved independence) under his jurisdiction, giving it the status of autonomy. The same happened in Estonia. The Phanar tried to act similarly in Latvia, although in this case it was less successful. The apex of such a policy was when Constantinople provided autocephaly to the Polish Orthodox Church in the 1920s, at the request of the Polish government. And by the way, it wasn’t for free (although for a very reasonable fee—Piłsudski17 was not generous). And this was done on the same pretext: that the Kiev Metropolia was allegedly, transferred illegally to the Moscow Patriarchate, at the end of the seventeenth century. And therefore, the Polish Orthodox Church, which was thought of by Constantinople as being a continuation of the Kiev Metropolia, received autocephaly. This was immediately challenged by the Russian Church, which did not recognize it as legitimate. It was only after the Second World War that the Polish Church received autocephaly a second time—from the Moscow Patriarchate.

—And why was the Kievan Metropolia alleged to be illegally transferred to Moscow? After all, the tomos was on this subject, and it had never been previously challenged.

—Well, they have to argue at least something to justify their actions, especially because they have been paid for it. And so they argued that the tomos was issued under pressure from the Ottoman authorities, which meant that it was uncanonical. Although by this logic, almost all the Patriarchs of Constantinople and their deeds should be recognized as uncanonical, since by the end of the sixteenth century they were instilled, deposed, and moved around as desired by the Ottoman authorities. And all the while they did everything that the Turks ordered them to do.

By the way, it may also be remembered that as millet-bashi, the Patriarch was an official of the Ottoman administration. What kind of pressure from the Turks can they be talking about? Obedience to the Sultan’s administration was his duty, to which the Patriarchate of Constantinople quite voluntarily agreed.

—Would I be right to understand that the Patriarch of Constantinople has a strange duality here—a form of doublethink? On the one hand, they never previously officially withdrew the tomos of 1686, and did not disavow it, while on the other hand they often say that the transfer was somehow illegal.18

—Yes. The renunciation of its own 1686 tomos in the twentieth century became part of the strategy of elevating the Cathedra of Constantinople and transforming its primacy of honor into a primacy of power; we are witnessing the continuation of this now in essence. It was just declared at the September Synaxis that only the Patriarch of Constantinople has the right to provide autocephaly, and only he can be the supreme arbiter in disputes between the Local Churches, etc. In fact, we have been observing this for the past hundred years, and the Constantinople Patriarchate is decisively and resolutely proceeding to do just that: to create within the Orthodox community of Churches a certain supreme center of power, and to give the Patriarch of Constantinople much greater prerogatives than the leaders of the other Local Churches.

—But how can these ambitions actually be enforced? To paraphrase the famous saying: How many army divisions does the Patriarch of Constantinople have?19

He has no real divisions. But firstly, there was a kind of push, which was given by the rare opportunist Meletius (Metaxakis), who for some time occupied the Cathedra of Constantinople. Here, for the record, it would not be superfluous to recall that the Phanar recognized the Russian “Living Church” schismatics, and joined in communion with them. The reason for all of this, unfortunately, was the typical desire of the Greek-Phanarites to maneuver and derive maximum profit from someone else’s problems, and even ills.

The Russian Church was thought of by the Greeks as a major competitor and obstacle to its own primacy. The desire to realize in ecclesiastical life the so-called Megali Idea20—the project of building a new Byzantium. Politically, an attempt to make this idea come true turned into a disaster for the Greeks in the Little Asia Catastrophe of 1922—a war lost to the Turks, with the massacre and mass exodus of Greeks from Asia Minor.

Imperial ambitions turned out to be very tenacious in the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and still many don’t see or notice that they have already put the Orthodox world on the verge of a large-scale schism.

There is a point of view that the Patriarch of Constantinople does not really decide anything. They say that they [foreign actors] come to him and say, “Do this.” And that’s that.

I would not say that. In my point of view, the dramatic nature of the current moment is the result of three forces colliding.

Firstly, it is Poroshenko’s regime, which today desperately needs autocephaly in order to distract the people from the real issues, which they are not able to solve, and for the sake of raising his approval rating before the presidential elections. And in general, if a religious war begins in Ukraine, then elections can be postponed for an indefinite period.

Secondly, it is the ambitions of Constantinople.

And thirdly, it’s the United States, for which everything that happens after the “Maidan” in Ukraine has become an opportunity to harm Russia as a political rival.

In the United States there is a huge Greek diaspora, which forms the main flock of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and it is by and large due to this flock that that patriarchate exists. It has a number of clans and individuals who are part of the elite of American society, part of the very same globalist elite that is now so heavily attacking Russia. Of course, these people are also acting through the Phanar today.

The result was a kind of resonance when the interests of three political players21, mixed together in the question of the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Church. And this is political. There is absolutely nothing religious about this problem!

I do not think that Patriarch Bartholomew was ordered to do anything. Rather, it can be argued that having felt interest and support from the U.S., he began to act in the Ukrainian issue much more boldly and confidently. At the same time, Patriarch Bartholomew, for all his ambitiousness, can not understand that what he is doing now can cause the collapse of the whole construct, under which he himself will be buried—I am referring to a crisis in the entirety of world Orthodoxy. Here, possibly he is spurred on, and encouraged to act in every possible way.

—What are the most likely next events?

—I do not presume to predict. Everything could turn around. But I still fear that in Ukraine there will be a great aggravation of confrontation on religious grounds. It does not matter what kind of new jurisdiction will be created there, to be under Constantinople or autocephalous. Obviously, the question of the redistribution of property, churches, and monasteries will immediately be raised; they will begin to forcefully seize them from the canonical Church. I think also that Orthodox believers will not so easily give them up, and that blood can be spilled.

—The tremendous risk of starting a conflict on an even larger scale is terrifying. How can this be summed up with a simple Christian conscience?

—They have already come to this. Constantinople apparently made a choice. And it is quite obvious that the actions of Constantinople did not only exacerbate the schism in Ukraine, but also led to a tremor throughout the entire Orthodox world.

It would have been hard to believe that earlier. Would you yourself, half a month ago, think that this would have happened?

A month ago, I already thought so. Because in geopolitics absolutely incredible things are happening today, inconceivable it would seem, a few years ago. Take the British Prime minister from whom we hear completely unfounded accusations against Russia in the “Skripal case” Can you imagine what happened with these Skripals? What is going on there, are they alive or not? Did someone evaluate their condition after the so-called poisoning? Do they have any proof, even minimal?

—Why did you think of that now?

—We live in a strange era. You can make any accusations against a political opponent and not support it with any evidence. You cannot uphold any principles, even the rules of decency, to speak of what is “black” as what is “white”, and vice versa. We see with horror that this has already come into the ecclesiastical environment, into the communion between the Local Orthodox Churches.

Constantinople is demonstrating this today by its steps. Our Patriarch arrived, and at a meeting with him, the Phanarites said that we would work together in the interests of ecclesiastical unity. I understand that some assurances were given, judging by the fairly optimistic mood of our primate at that time. But just one day later at the Synaxis, Patriarch Bartholomew says something completely different, and within a week he appoints two exarchs to Ukraine. Lies and hypocrisy are always particularly disgusting when committed amidst a backdrop of piety.

Unfortunately, the so-called Great Byzantine Idea has become of the highest value for the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which has forced out Christ’s Sermon on the Mount. So the Patriarchate, which a century and a half ago condemned ethnophyletism—that is to say Ecclesiastical Nationalism—as a heresy, has now been eaten by this nationalism.

I am also a Greek and I find patriarch

Bartholomews actions destructive and

Appalling.

I am an advocate of orthodox brotherhood

And view Russia as the third Rome.

We should also keep in mind that the churches

Of greece, cyprus, Alexandria, and Jerusalem

Led by Greeks have excellent relations with

The Russian church and recognize

Metropolitan onuphry as the real bishop

Of ukraine.

In the end patriarch bartholomew's actions

And claims are creating tensions and

Misunderstandings. It might be time

For orthodox Greeks to repudiate them.

A better slogan for now. We will see who will stand with us.

O blessed St. Alexander Nevsky, contend thou against those who wage war on us!

I truly believe that this should become the motto for the Orthodox, when we fight that heretical greko- turk and his mafia in bishops clothing. This creature is ready to do more damage to the Church than any of his islamic friends are capable of doing, and he will do it for $15 mill! Truly, when you consider that such people are able to live after doing such things, you understand how loving, merciful and long suffering God is. This judas will pay for his betrayal.

It disturbs me to see that this website is so willing to enter into political polemic by publishing outrageously biased statements that have nothing to do with Church life. It demonstrates that we have left postmodernism behind and now live in a Harold Pinteresque worldnof nom-contingent pseudorealities managed by media campaigns and troll-farms.

Desire of the Greeks of Constantinople

And Asia Minor to be liberated from Turkish

Genocide.

It has nothing to do with the morally

Reprehensible and uncanonical actions

Of the phanar in Ukraine.

The phanar is definitely not concerned with

Greek interests. The interests of greece

And cyprus lie with Orthodox russia.