10. Brotherhoods

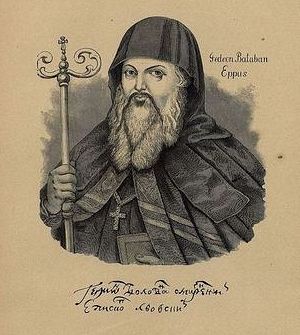

Bishop Gideon Balaban of Lvov, defender of Orthodoxy from the Polish Catholics As their leadership was undermined, and as the “divide and conquer” strategy was used against their Church, the Orthodox in Poland and Lithuania began to form brotherhoods as a counter-force. The remaining Orthodox landowners (who still retained the legal power of patronage) and city brotherhoods took a major role in protecting Orthodox churches and affairs. The Lvov Dormition Brotherhood, dating back to midfifteenth century, was the oldest brotherhood, and served as the example to others. These Orthodox brotherhoods worked to stem state-supported Roman Catholic prosyletism, opening Orthodox schools and publishing Orthodox books in Cyrillic. For obvious reasons, they were a thorn in the side of Latin-leaning Orthodox bishops, who often sought to eliminate them. The Polish king was happy to oblige these bishops, because this would ultimately give him more direct authority over his Orthodox subjects. The brotherhood schools in Lvov, however, found a supporter in its local bishop, Gideon Balaban (1530–1607), who had at one time participated in negotiations with Catholics but then took a strong stance against union with them, to which he held until his death.

Bishop Gideon Balaban of Lvov, defender of Orthodoxy from the Polish Catholics As their leadership was undermined, and as the “divide and conquer” strategy was used against their Church, the Orthodox in Poland and Lithuania began to form brotherhoods as a counter-force. The remaining Orthodox landowners (who still retained the legal power of patronage) and city brotherhoods took a major role in protecting Orthodox churches and affairs. The Lvov Dormition Brotherhood, dating back to midfifteenth century, was the oldest brotherhood, and served as the example to others. These Orthodox brotherhoods worked to stem state-supported Roman Catholic prosyletism, opening Orthodox schools and publishing Orthodox books in Cyrillic. For obvious reasons, they were a thorn in the side of Latin-leaning Orthodox bishops, who often sought to eliminate them. The Polish king was happy to oblige these bishops, because this would ultimately give him more direct authority over his Orthodox subjects. The brotherhood schools in Lvov, however, found a supporter in its local bishop, Gideon Balaban (1530–1607), who had at one time participated in negotiations with Catholics but then took a strong stance against union with them, to which he held until his death.

The brotherhoods continued to thrive under conditions that ranged from less than favorable to outright hostile. And, as we shall see, by the providence of God they were to receive help from some unexpected sources.

In 1492, the successor to Prince Kasimir of Poland, Alexander, took control of the western Russian territories that were under Polish rule.

With his approval, Joseph Bolgarinovich became the Kiev Metropolitan. Joseph was a strong supporter of the Florence Union, and with his help Alexander initiated new outright persecutions of the Orthodox. Even Alexander’s wife, Elena, who was Orthodox and had been promised in writing in her marriage agreement that she could continue confessing Orthodoxy, was deprived of her Orthodox father-confessor and house church. As Elena was the daughter of the Moscow Grand Prince John III, this Catholic fanaticism cost Lithuania greatly. Moscow began a war with Lithuania, which lost several ancient principalities presided over by Orthodox princes, who annexed these lands to Moscow. In 1514, under Alexander’s successor Sigismund I, the western Russian city of Smolensk also broke away from Lithuania. Sigismund changed his policy to overt tolerance of Orthodoxy, but made greater use of his power to appoint clergy, and mixed unworthy hierarchs and clergy into key clerical positions, thus humiliating and weakening the Orthodox leadership.

In Galicia, which was directly under the Polish king, things were worse. The Orthodox diocese of Galicia was annulled, and all Church affairs and properties were presided over by a vicar of the Kiev Metropolitan. (Previously, the Metropolitan had been titled, “Of Kiev and Galich.”) In 1509, the Polish king granted the Catholic Archbishop of Lvov power to choose this vicar. But the Orthodox Galicians opposed this measure and elected their own vicar, and a thirty-year bribery war ensued between the Orthodox and Catholics, ending with the appointment of Macarius Tuchansky in 1539 as bishop of the reinstated Galicia diocese.

Recall now that the Metropolitan of Kiev was physically based in Vilnius. Therefore, whatever was happening politically in Lithuania affected all the Orthodox in the western lands that were under Poland. The ruling Metropolitan at this time, Joseph Soltan, elected under Sigismund I, was a well respected hierarch, who was able to finally restore the vicariate in Galicia to the Kiev Metropolitanate. But the rights won by the Orthodox in these lands were now under a new threat.

Religious freedom for all confessions had taken a brief turn for the better with the introduction of Protestantism in Lithuania through Sigismund’s successor, Sigismund August II. But to fight Protestantism in Poland, the Catholics increased their own vigilance, which could not but aim another blow against Orthodoxy, especially since through the initiative of such noblemen as Prince Ostrogsky, the Orthodox and Protestants formed an alliance to defend themselves from the Catholics. These hard times for the Church were preceded by the Union of Lublin,15 and the arrival of Jesuits in Poland and Lithuania. Politically, Lithuania and Poland were now united into one state, which facilitated the infiltration of Polish Catholics into previously Orthodox aristocratic properties, positions of authority, and seats in the Sejm. Their decisions and directives were one-sided against the local people and their Orthodox faith. This culminated after the death of Sigismund II, who had no heirs. Polish rulers came into power, determined to force religious unification in the steps of political unification.

The Catholic measures against the rapid spread of Protestantism in Poland and Lithuania worked in Poland, but fared less successfully in Lithuania. The Jesuits, who started gaining acceptance by doing charity work, carried out the mission. But once Protestantism was sufficiently weakened in Poland, the Catholics turned their zeal against the remaining Orthodox.

The Jesuit Order is a subject all to itself, but in brief strokes we will say that the Jesuits take a vow of unquestioning submission to the Pope, and education and erudition have always been their main instruments among the masses. A large, influential school, encompassing everything from elementary school to college, was established in Vilnius. Having nothing that could compete with it, the Orthodox elite class also sent their children to study there. By 1586 the school had seven hundred students and over fifty teachers. The school demanded unquestioning submission to the Jesuit teachers, and within its walls a generation of apostates from Orthodoxy was soon brought up. A special school was also opened in Rome that carefully studied the traditions and specifics of the Eastern European Orthodox cultures, to prepare instructors and missionaries for work among the Orthodox

The Unia was seen as a convenient and tactful step in this direction. The Unia, or uniatism, was a policy developed by Rome in order to bring Orthodox and other non-Roman Catholic believers under the authority of the Pope. These believers were to be allowed to retain their unique rituals and customs, and even certain aspects of their theology, as long as they submitted to papal authority. Uniate churches, also called “Greek Catholic” or “Byzantine-Rite Catholic” churches, exist up to today in numerous parts of the world.16

As the Orthodox Church was being undermined in Poland-Lithuania under Roman Catholic rule, its believers were looked down upon by Latin clerics who wanted them to accept the Unia. Here is the essence of what the famous Polish Jesuit orator Peter Skarga wrote about the Orthodox in his book On the Union of the Churches (1577):

1. The married life of the priests, in taking care only for the worldly, has made them crude and turned them into slaves;

2. The Greeks left the Slavs with the Slavonic language when they converted them to Christianity in order to leave them in ignorance, because it is only possible to advance in learning through Latin and Greek, and Slavonic can never be used in schools where theology is taught. Not so for the Catholics, for Latin is used everywhere in their schools. Even the Christians of India can converse with Christians in Poland;

3. The laity’s intervention into religious affairs, and the humiliation of the clergy. The Unia must do away with all this evil; all the Orthodox need to do is to accept the teaching of the Roman Church, and the supremacy of the Pope, but they can keep their old rites.

The Unia began to appeal to the upper crust of Orthodox society in Poland-Lithuania. The privileged position of the Catholics and their studied disdain for the “ignorant slaves” of grassroots Orthodoxy broke down the resistance of this upper class with the lure of becoming just like the Polish aristocracy. Russian monasticism—with its long beards, manual labor, and down-to-earth approach—had not been transformed into the Jesuit image of Catholicism—with its clockwork order and clean-shaven faces—and was completely foreign to the new liberal Protestantism. In short, the upper class Orthodox were suffering from an inferiority complex that could only be remedied, they thought, by casting off the bone of contention—traditional Orthodoxy. Catholic bishops participated in the Senate, while the Orthodox hierarchs were in submission to a Patriarch now under the Turkish yoke and answerable to a sultan. The Polish king carefully cultivated this rift by appointing Orthodox bishops who would broaden it even further. The bishops were mostly from the aristocracy, and had no problem with handing over the Orthodox monasteries in their sees to the Catholic Church. They were often simply careerists, and no attention was paid to the fact of their married life, which would have normally excluded them from a bishopric in the Orthodox Church. It was a dismal situation for the Orthodox Church in Galicia and Volhynia, yet those very people whom the Jesuits disdained—the peasants, the working classes, and the outcast Orthodox landowners—were the ones who preserved Orthodoxy.

Prince Constantine Ostrogsky. Here is an interesting turn of providence. Prince Andrei Kurbsky was a fugitive from Tsar Ivan the Terrible. He was a friend and patron of St. Cornelius, the abbot of the Pskov Caves Monastery, who had died a martyr’s death at the hands of the enraged Tsar, who thought the saint was harboring the disfavored Kurbsky. But Kurbsky had fled to Lithuania, and seeing the Orthodox in dire straights, used his own finances to fight against Catholic and Protestant propaganda. He fervently began publishing books on Orthodox apologetics, and compelled his relatives to help him. Another laborer in the field of Orthodox enlightenment in these western lands was Prince Constantine Ostrogsky, who opened a school on his own property, along with a printing press. This printing press even sent Orthodox service books to Russia. Both Ostrogsky and Kurbsky corresponded with and supported the Orthodox brotherhoods in Galicia. Ostrogsky also took upon himself the herculean task of publishing what is now known as the Ostrog Bible (1581), the first complete printed edition of the Bible in the Church Slavonic language.

Prince Constantine Ostrogsky. Here is an interesting turn of providence. Prince Andrei Kurbsky was a fugitive from Tsar Ivan the Terrible. He was a friend and patron of St. Cornelius, the abbot of the Pskov Caves Monastery, who had died a martyr’s death at the hands of the enraged Tsar, who thought the saint was harboring the disfavored Kurbsky. But Kurbsky had fled to Lithuania, and seeing the Orthodox in dire straights, used his own finances to fight against Catholic and Protestant propaganda. He fervently began publishing books on Orthodox apologetics, and compelled his relatives to help him. Another laborer in the field of Orthodox enlightenment in these western lands was Prince Constantine Ostrogsky, who opened a school on his own property, along with a printing press. This printing press even sent Orthodox service books to Russia. Both Ostrogsky and Kurbsky corresponded with and supported the Orthodox brotherhoods in Galicia. Ostrogsky also took upon himself the herculean task of publishing what is now known as the Ostrog Bible (1581), the first complete printed edition of the Bible in the Church Slavonic language.

Unfortunately, however, this princely support soon waned, and the aristocracy was Polonized. The succeeding generation later even warred against Orthodoxy, as did both Kurbsky’s son Dmitry and Ostrogsky’s son Janush. It was left to the people, the communities, brotherhoods and their schools, to carry on this publishing work. In the late fourteenth century, something totally unexpected by the strictly hierarchical Catholic Church had taken place: the Eastern Patriarchs had blessed the brotherhoods to “police” those who departed from Orthodox teaching, including the Orthodox bishops. In 1586, Patriarch Joachim V of Antioch travelled through Russia at the behest of Patriarch Jeremiah of Constantinople. It will be recalled that the believers of the Kiev Metropolitanate had turned to the Patriarchate of Constantinople for help during this period of extreme difficulties. When Patriarch Joachim reached Lvov17 and saw how dire the situation had become, he, acting on behalf of Patriarch Jeremiah, gave a charter to the ancient Lvov Orthodox Brotherhood to elect its own church wardens, conduct Church affairs, and excommunicate those who worked against the teachings of the Orthodox Church. The charter acknowledged the Lvov Brotherhood as the authority over other brotherhoods. It had its own hospital, printing press, and school, and its influence even gave trouble to the Unia-inclined bishops. In 1589 Patriarch Jeremiah visited Lvov himself, and gave his approval to the brotherhoods.

By the time Patriarch Jeremiah arrived in Lvov, the Orthodox hierarchy was in deep Latin captivity, and its authority was totally undermined. The Metropolitan of Kiev had been married twice. The bishops of Peremysl and Pinsk were living with their wives. The bishops lived like the aristocrats they were, in castles, surrounded by servants, eating delicacies, defended by cannons (the iron kind). They fought amongst themselves and started wars. They made money from their properties, but none of it went to the diocese. On the contrary, their armed attacks against their neighbors, some ending in murder, left no doubt that no help in Church affairs could be expected from them. Therefore, the Patriarch gave even more power to the Lvov Brotherhood, including the power to dismiss priests. He also encouraged the formation of new brotherhoods. The Patriarch removed Metropolitan Onuphrius of Kiev, but he did not have much to work with in appointing a replacement. Considering how displeased all the bishops were with his support of the brotherhoods, and the Jesuits’ vigilance in using this displeasure to their own advantage, Jeremiah’s departure was followed by heated discussions among the bishops against Constantinople and in favor of the Unia with Rome.

The new Metropolitan, Michael Rogoza, was Orthodox, but weak. He was no match for the other bishops, who were sent to Rome to accept the Unia. They presented a document to him with conditions for acceptance: the protection of Orthodox dogmas and rites, and protection against the brotherhoods. Metropolitan Michael signed it. But the two bishops pushing for the Unia acted entirely without his approval, and made so many concessions to the Latins that the Metropolitan was aghast. Rumors flew around the laity that they had been betrayed, and the Metropolitan completely lost his authority in their eyes. The brotherhoods called for action.

Confusion arose among the bishops, each pointing a finger at the other, and the two most determined in favor of the Unia—bishops Cyril Terletsky and Hypatius Potei—made haste to Rome, there to submit to the Pope. They accepted the filioque, indulgences, purgatory, and papal supremacy. Only the Orthodox rites were left intact. Pope Clement VIII was overjoyed, and created a special medal for the emissaries, reading, “Ruthenis receptis” (the Russians in Galicia were called by the Western world “Ruthenians”). At home, however, people reacted very differently to the agreement. The brotherhoods and the priests called Terletsky and Potei traitors. Constantine Ostrogsky published a work entitled “St. Cyril of Jerusalem on the Antichrist”—showing how the Roman Pope fit the description. He called upon the nobles and lower classes to revolt. Even many of the Catholics in Galicia could feel in their bones that nothing good would come of this. How could anything good come of deception?18

11. St. Job of Pochaev

St. Job of Pochaev. Eighteenth-century icon One great light for the Orthodox during these troubled times was St. Job of Pochaev (commemorated May 6, August 28, and October 28). Born Ivan Zhelezo in Galicia in about 1551, he left home at the age of ten for the Monastery of the Transfiguration at Ugornits, where he received the tonsure at the age of twelve. At the age of thirty-one he was ordained to the priesthood. At the repeated requests of Constantine Ostrogsky, St. Job was transferred to the Monastery of the Holy Cross at Dubensk, one of Ostrogsky’s properties. He served as the superior of that monastery for the next twenty years, and made ample use of Ostrogsky’s printing facilities to defend Orthodoxy against the teachings of Protestants that were just beginning to spread and, of course, against the Latin innovations. Under his guidance, many of the teachings of the Holy Fathers of the Orthodox Church were translated, and they contributed mightily to his labors in educating the Orthodox population and confirming them in their Faith. St. Job’s growing popularity, as well as the anger of the Roman Catholics, compelled him in 1604 to move to the Pochaev Monastery of the Dormition of the Mother of God, located in a more remote area. His severe monastic struggles and holy life inspired the brethren of Pochaev, and they made him their superior. He expanded the size of the monastery greatly and continued his educational activity, acquiring a printing press for the monastery for this purpose. He reposed in 1651, at the age of one hundred.

St. Job of Pochaev. Eighteenth-century icon One great light for the Orthodox during these troubled times was St. Job of Pochaev (commemorated May 6, August 28, and October 28). Born Ivan Zhelezo in Galicia in about 1551, he left home at the age of ten for the Monastery of the Transfiguration at Ugornits, where he received the tonsure at the age of twelve. At the age of thirty-one he was ordained to the priesthood. At the repeated requests of Constantine Ostrogsky, St. Job was transferred to the Monastery of the Holy Cross at Dubensk, one of Ostrogsky’s properties. He served as the superior of that monastery for the next twenty years, and made ample use of Ostrogsky’s printing facilities to defend Orthodoxy against the teachings of Protestants that were just beginning to spread and, of course, against the Latin innovations. Under his guidance, many of the teachings of the Holy Fathers of the Orthodox Church were translated, and they contributed mightily to his labors in educating the Orthodox population and confirming them in their Faith. St. Job’s growing popularity, as well as the anger of the Roman Catholics, compelled him in 1604 to move to the Pochaev Monastery of the Dormition of the Mother of God, located in a more remote area. His severe monastic struggles and holy life inspired the brethren of Pochaev, and they made him their superior. He expanded the size of the monastery greatly and continued his educational activity, acquiring a printing press for the monastery for this purpose. He reposed in 1651, at the age of one hundred.

The Pochaev Lavra of the Dormition of the Mother of God, as it looks today.

The Pochaev Lavra of the Dormition of the Mother of God, as it looks today.

12. The Council of Brest

In 1596, a council was called in the city of Brest-Litovsk, located in what is now Belarus. It was a large council, with two patriarchal exarchs present—Nicephorus from Constantinople and Cyril Lukaris from Alexandria. It was divided into two camps: the Orthodox and the Uniate. The Orthodox had to meet in a private home, because BrestLitovsk was in the diocese where Potei ruled, and he had ordered all the churches locked against them. Nicephorus invited the Uniate Metropolitan and four other bishops three different times to the Orthodox council, and when they did not appear, the exarch defrocked them and rejected the Unia. The Unia council likewise anathematized the Orthodox council and triumphantly signed the act of Unia, which had been already ratified by the Polish king. They pronounced a thunderous rebuke against all the Orthodox—saying that their bishops were in disobedience and had betrayed their Church, that the Greek exarchs were spies for the Turkish sultan, and that all the Orthodox faithful were criminals against their ecclesiastical authorities and the will of their king. Thus, this “Union of Brest,” as it is called, was anything but a union, and the consequences of the debacle would be felt through the ages, even to our own day, leaving a trail of violence and injustice.

Just as the Jews prevailed upon Pilate to crucify Christ, so did the Uniates call for punishment, and outright persecutions against the Orthodox were not slow to come. Nicephorus was imprisoned in Malbork Castle and starved to death, while Cyril Lukaris fled. Uniate bishops removed all Orthodox priests from their parishes and appointed Uniates. Constantine Ostrogsky was pursued by tax collectors. The brotherhoods were declared terrorists and their activities scrutinized. Churches were seized from the Orthodox, and their priests were beaten and imprisoned. The St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev was taken over by Uniates. Only the Kiev Caves Lavra was able to withstand the aggression, through the prayers of its saints. From top to bottom, throughout society, Uniates were given special preferences over the Orthodox. The non-Orthodox landowners deprived their Orthodox peasants of their churches and clergy, either giving Church property to the Uniates or turning it over to local Jews. In the latter case, the Orthodox were forced to pay a fee every time they used the churches to the Jewish owners, who were given leave to humiliate the faithful and blaspheme against their religion with impunity.

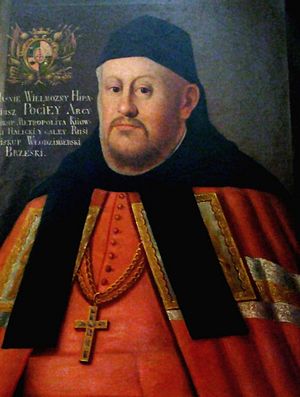

Hypatius Potei during his time as the Uniate Metropolitan of Kiev. Seventeenth-century portrait Hypatius Potei succeeded Rogoza as Metropolitan of Kiev, and the persecutions increased. More churches were seized, while the clergy and then the brotherhoods were attacked. The pressure led to an uprising and an attempt on Potei’s life, which only increased the pressure against the Orthodox.

Hypatius Potei during his time as the Uniate Metropolitan of Kiev. Seventeenth-century portrait Hypatius Potei succeeded Rogoza as Metropolitan of Kiev, and the persecutions increased. More churches were seized, while the clergy and then the brotherhoods were attacked. The pressure led to an uprising and an attempt on Potei’s life, which only increased the pressure against the Orthodox.

Here is one illustration, taken from Metropolitan Makary (Bulgakov’s) History of the Russian Church, showing what the clergy and faithful who opposed the Unia had to endure. Just three months after the signing of the Brest Union, Archimandrite Sophronius of the Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius appeared before the local magistrate and resigned his position as abbot of the monastery:

I have had to endure too much from the local people for commemorating the [Uniate] Metropolitan. I had done this against my own conscience and convictions, but from now on I will not supplicate God’s mercy for the Metropolitan and do not want to be superior of the monastery, wishing to be a simple monk somewhere and preserve my conscience, rather than pray for the current Metropolitan.19

Sophronius soon reneged on this resignation, remained abbot, but refused to commemorate the Metropolitan. The Holy Trinity Brotherhood became the only congregation in Vilnius to actively oppose the Unia, and here is what happened to them.

The brotherhood lost its permission to build its church, so they began construction on the other side of the street, on the property of two Orthodox sisters from Smolensk, with the surname Volevich; and therefore the magistrate could not legally stop them. The church was consecrated in 1598, and all the Orthodox people of Vilnius planned to attend the Paschal services there, as they had no other church. Metropolitan Makary writes:

This is the time that the enemies of Orthodoxy chose to mete out the greatest insult to them. On the eve of Great Saturday, a crowd of fifty students from the Jesuit academy, led by the Catholic priest Geliashivech, came to the yard where the monastery school and church were located. First they entered the school (collegium)…20

In the school they began a dispute with the teachers.

From the school they proceeded to the church, where the doors were already locked, and entered the altar with extreme indecorousness and threw the cross and Gospels from the altar; from there they left through the royal doors and entered the center of the church where the epitaphion21 stood, grabbed it and threw it from side to side; and when the church attendants, who were cleaning the church for the feast, tried to dissuade the rabble, they were cursed at and beaten. On the very feast of Christ’s Resurrection, a crowd of students again appeared in the church and, stepping around the epitaphion, tried again to throw it over, mocked the church ceremonies, shoved the worshippers, poked the women with hat pins, and pushed towards the altar, not allowing anyone to receive Holy Communion, so that Priest Gerasim was barely able to get them to move at least a little to the side. Even more brazenness and audaciousness did the riotous Jesuit pupils allow themselves the same day at the evening services in the brotherhood church, where this time they came armed. They grouped together around the church: some by the church doors, others in the narthex, others in the center of the church, and a fourth group on the kliros—pushing and shoving people everywhere and piercing them with hat pins, swiping the women on their lips and faces with their fingers and hands, and uttering shameless words.22

The students proceeded to beat the clergy, answering pleas for order with blows to the face. They ran to the school to beat those who crossed their path, then went out to the street, where they were joined by several hundred more Jesuit students and citizens belonging to the Latin faith. This entire throng, armed with rifles, bows and arrows, stones, and axes began storming the monastery collegium and monks’ quarters, where one of the Smolensk noblewomen was staying. The students then carried out a pogrom. They did the same thing the next day at the Liturgy, wreaking havoc on the school and the cemetery, and beating all those who came to the services.

The Jesuits did all this with the aim of provoking the Orthodox to a fight, so that measures could be taken against them. But however painful it was, the Orthodox people endured it and did not fight.23

Despite all their efforts and those of the Jesuits, the Uniates never gained the acceptance they had hoped for. The Orthodox people held them in contempt, and the nobles were ashamed of them, in many cases skipping right over them into the Latin Church. The Uniates were neither fish nor fowl, and everyone could see it. Rather than rising in the estimation of the Polish government, the Uniates found themselves in greater contempt, and never did receive the coveted senate seats.

This was because neither Rome nor the Polish authorities ever really intended the Unia to be an end in itself, but only a step in the direction of complete Latinization. Even Metropolitan Hypatius Potei saw things the same way—at least that was how it looked to the more Orthodoxleaning Uniate clergy. He had accepted so much of the Roman Catholic dogma that any remaining Orthodox rites had lost all meaning. The married clergy clung to these vestiges of Orthodox practice, while the Metropolitan strove to reform monasticism according to the Latin model. He and his successor worked tirelessly to bring the Uniates closer to Latin Catholicism. A special order called the Basilian Order was created, and the Uniate clergy and monastics were made subject to it, so that even the Eastern rite began to melt away in Uniate monasteries.

Again, let us look at the broader geographical-historical picture of that time period. Moscow was reeling from the “Time of Troubles,”24 and fighting off military campaigns directed against it by the Poles and Lithuanians. The retreating Western armies were taking out their frustrations on their Orthodox subjects.

Southern Russia, from the area east of the Dniepr River up to Galicia, Lithuania, and what is now Belarus, was called Little Russia. While we are speaking of Little Russia, we will pause to explain where the term “Little Russia” came from. Μικρὰ Ῥωσσία was the name used first by Greek bishops for those Russians living in greater Lithuania, and then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the Polish perspective, Lvov (Galicia), Vilnius, and cities in present-day Belarus were “theirs” (Polish), while Kiev and the steppes beyond were called the okraina (Ukraine), which means outlying territories, or borderlands. Ethnically, as the Greeks and, in fact, as the Little Russians themselves understood it, the people of Little Russia and Greater Russia were one and the same, of the same religion, with only some differences in local color.

The Orthodox Little Russian peasants and tradesman were in strict subjection to the Polish-Lithuanian princes; however, rising from the steppes was a free, warrior class—the Cossacks.

While the Orthodox in Galicia were in captivity, the Little Russians enjoyed more freedom. It was becoming so intolerable for the Galician and Volhynian Orthodox that even some Catholics and Protestants began to stand up for them.

One Volhynian deputy, the zealously Orthodox Lavrenty Drevinsky, spoke to the Sejm in 1620:

In the large cities the churches are sealed, church property is stolen, there are no monks in the monasteries, and they are being used as cattle barns. Children are dying without baptism; the dead are taken out of the city without funerals, like fallen beasts; husbands and wives are living together without the blessing; people die without Communion. This is how it is in Mogilev, Orsha, and Minsk. In Lvov a non-Uniate cannot be a member of a guild; it is not possible to openly visit the sick with the Holy Gifts. In Vilnius they have to carry the bodies of the Orthodox deceased through the gates by which refuse is removed.25

Support also came from Mt. Athos in the form of letters exposing the error of the Latins. But the greatest support to the Orthodox in Little Russia, and the greatest threat to those who persecuted them, came from the Cossacks. The Cossacks defended them, not with the pen, but with the sword.

The Orthodox response to Latinization in Little Russia and Volhynia actually produced a flowering of Orthodox enlightenment in these places. Instead of giving in and dying out, the brotherhoods multiplied. The Cossack leaders along with Orthodox noblemen provided the funds to open schools, and new monasteries opened to replace the confiscated ones. There were always more Orthodox monastics than Uniate ones—the Orthodox monasteries usually had eighty to two hundred monks, while the Uniate monasteries were often empty. Pillars of Orthodox monasticism opened and flourished: in addition to the Pochaev Monastery in Volhynia, the Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius, and the Brotherhood (Bratsky) Monastery in Kiev, as well as the Kiev Caves. More printing presses were running, and Orthodox theologians were called from Greece and Mt. Athos to raise the level of knowledge of the Orthodox Faith. Meanwhile, the Uniate bishops, who often had dubious pasts, received almost no support—either from the Latinized nobility, or, less so, from the brotherhoods.

Lavrenty Drevinsky spoke about this also at the Warsaw Sejm in 1620:

If certain of our clergy had not apostatized from their lawful hierarchy [that is, the Constantinople Patriarch], if those who had left us [the Uniates] had not fought against us, then such learning, such schools, such worthy and learned people would not have appeared among the Russian people and the study in our churches would have remained, as before, covered by the dust of carelessness.26

Metropolitan Makary (Bulgakov) in his History further comments that “in general, the situation of the Unia in the Western Russian lands was still very unstable and unreliable, because it was both introduced and supported by force alone. The Orthodox were at enmity with it; the larger part of the Latins, both clergy and lay, did not sympathize with it; and even the Uniates themselves did not like it—at least the lower clergy and people, who accepted it and upheld it, not at all due to conviction, but rather against their will. The Unia’s only support came from the zealot King Sigismund III, and without his continual support the Unia would have inevitably fallen.”27

Nevertheless, without the king’s permission there could be no freely acting Orthodox hierarchy.

13. Help Comes from the Eastern Patriarchs

The dearth of Orthodox bishops and clergy caused the Patriarch of Constantinople to send Patriarch Theophanes of Jerusalem who, at the request of the faithful, restored the Orthodox hierarchy. Theophanes, together with a Bulgarian bishop and one other bishop, consecrated worthy hierarchs secretly in Kiev. The Polish government did not recognize these bishops; those other than the Kiev Metropolitan Job (who locked himself in his quarters in Kiev) could not even enter their own dioceses for fear of arrest, and lived under the physical protection of Cossacks in Kiev or in various monasteries.

Again, the Orthodox responded with writings and apologetics, forcefully showing that the appointed Orthodox bishops were lawful, and explaining the error of the Unia. The Cossacks, who were needed to fight the Turks, announced that they would do nothing until order was restored to the Orthodox Church. This caused the senate to soften toward the faithful, but this détente did not last long. It ended abruptly with the murder of the Uniate Bishop Joasaphat Kuntsevich in 1623.

14. Joasaphat Kuntsevich

Joasaphat Kuntsevich, depicted as a saint by the Roman Catholics Kuntsevich, the son of a cobbler, was a fanatical Uniate whose persecution of the Orthodox cried out to heaven for its cruelty. His actions are historically reflected in a letter to him from the Lithuanian Prince Sapega, to whom Kuntsevich had turned for protection against the angry masses:

Joasaphat Kuntsevich, depicted as a saint by the Roman Catholics Kuntsevich, the son of a cobbler, was a fanatical Uniate whose persecution of the Orthodox cried out to heaven for its cruelty. His actions are historically reflected in a letter to him from the Lithuanian Prince Sapega, to whom Kuntsevich had turned for protection against the angry masses:

I admit, that I, too, was concerned about the cause of the Unia and that it would be imprudent to abandon it. But it had never occurred to me that Your Eminence would implement it using such violent measures…. You say that you are “free to drown the infidels [i.e., the Orthodox who rejected the Unia], to chop their heads off,” etc. Not so! The Lord’s commandment expresses a strict prohibition to all, which concerns you also. When you violated human consciences, closed churches so that people should perish like infidels without divine services, without Christian rites and sacraments; when you abused the King’s favors and privileges—you managed without us. But when there is a need to suppress seditions caused by your excesses you want us to cover up for you…. As to the dangers that threaten your life, one may say that everyone is the cause of his own misfortune. Stop making trouble, do not subject us to the general hatred of the people and you yourself to obvious danger and general criticism…. Everywhere one hears people grumbling that you do not have any worthy priests, but only blind ones…. Your ignorant priests are the bane of the people…. But tell me, Your Eminence, whom did you win over, whom did you attract through your severity?… It will turn out that in Polotsk itself you have lost even those who, until now, were obedient to you. You have turned sheep into goats, you have plunged the state into danger, and maybe all of us Catholics—into ruin…. It has been rumored that they (the Orthodox) would rather be under the infidel Turk than endure such violence…. You yourself are the cause of their rebellion. Instead of joy, your notorious Unia has brought us only troubles and discords and has become so loathsome that we would rather be without it!28

The people became so enraged against Kuntsevich that on May 22, 1620, they gathered near the Holy Trinity Monastery to speak out. But here they met their death: “These people suffered a terrible fate: an armed crowed of Uniates surrounded the monastery and set it on fire. As the fire was raging and destroying the monastery and burning alive everyone within its walls, Joasaphat Kuntsevich was performing on a nearby hill a thanksgiving service accompanied by the cries of the victims of the fire….”29

In 1623 Kuntsevich was killed by the people of Vitebsk. Although he had instigated violent acts against many Orthodox, he himself was canonized as a “martyr” by Pope Pius IV in 1867. Various legends were dreamed up by the Catholics about his “miracles.” In 1995, in anticipation of the fourth centenary of the “Union of Brest,” Pope John Paul II praised him as an “an illustrious victim .… whose martyrdom merited the unfading crown of eternal glory.”30

After Kuntsevich’s death, persecutions against the Orthodox became so ubiquitous and intolerable that Metropolitan Job of Kiev in 1625 applied to Tsar Michael of Moscow to receive Little Russia as part of Russia. He was refused at the time, since Russia, only recently freed from Polish incursions, did not want to go to war with Poland over this issue. However, conditions continued to deteriorate. Previous concessions that had been made to the Orthodox by the Polish authorities were reversed; Orthodox churches had no legal recourse when priests were attacked and property stolen.

This provoked the Cossacks, who began raids against the Poles, which provoked the Poles to greater persecutions and cruel punishments and executions.

15. Metropolitan Peter Mogila

Metropolitan Peter Mogila. Eighteenth-century portrait. Here we must note also the important influence of Peter Mogila,31 Metropolitan of Kiev and Galich from 1632 until his death in 1646. Peter Mogila was born to a Moldavian boyar family in Suceava, Moldavia, on December 21, 1596. In Mogila’s time, the Romanian principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia, and part of Transylvania were still using Old Church Slavonic in their churches, and he cherished his ties to Slavic Orthodoxy. In the 1620s he travelled to Kiev and entered the Kiev Caves Lavra, eventually becoming its abbot, and the Metropolitan of Kiev. His influence as the head of the Orthodox Church in Kiev was far-reaching and timely. Respected by all due to his family connections with several European royal houses, he was able to negotiate with the Polish Sejm for the easing of restrictions against the Orthodox. Mogila also opened an institute of higher learning in Kiev that reached a very high level of educational quality, and then he proceeded to open schools throughout the area that would become Ukraine. In order to more greatly encompass all Orthodox thought, his schools taught in Latin, Greek, and Slavonic, and received students from all levels of society. Even the Uniate bishops had to admit with great consternation that their own educational institutions were paltry in comparison with those of Peter Mogila.

Metropolitan Peter Mogila. Eighteenth-century portrait. Here we must note also the important influence of Peter Mogila,31 Metropolitan of Kiev and Galich from 1632 until his death in 1646. Peter Mogila was born to a Moldavian boyar family in Suceava, Moldavia, on December 21, 1596. In Mogila’s time, the Romanian principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia, and part of Transylvania were still using Old Church Slavonic in their churches, and he cherished his ties to Slavic Orthodoxy. In the 1620s he travelled to Kiev and entered the Kiev Caves Lavra, eventually becoming its abbot, and the Metropolitan of Kiev. His influence as the head of the Orthodox Church in Kiev was far-reaching and timely. Respected by all due to his family connections with several European royal houses, he was able to negotiate with the Polish Sejm for the easing of restrictions against the Orthodox. Mogila also opened an institute of higher learning in Kiev that reached a very high level of educational quality, and then he proceeded to open schools throughout the area that would become Ukraine. In order to more greatly encompass all Orthodox thought, his schools taught in Latin, Greek, and Slavonic, and received students from all levels of society. Even the Uniate bishops had to admit with great consternation that their own educational institutions were paltry in comparison with those of Peter Mogila.

16. St. Athanasius of Brest-Litovsk and the Cossack Uprisings

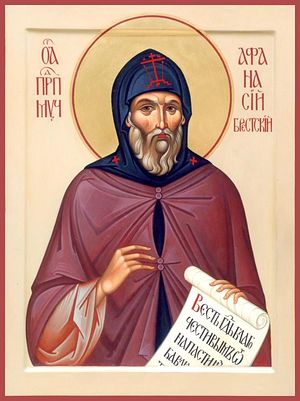

St. Athanasius of Brest-Litovsk. The year 1596—the year of the institution of the Brest Union— was, in addition to the year of the birth of Metropolitan Peter Mogila, the year of the birth of one of the Orthodox Church’s great heroes in the struggle against the Unia, St. Athanasius of Brest-Litovsk (†1648, commemorated September 5). The son of an Orthodox Lithuanian nobleman, he acquired an outstanding education from schools run by the Orthodox brotherhoods, and at the age of thirty-two became a monk at the Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius. After living in other monasteries and being ordained to the priesthood, St. Athanasius was tasked by Metropolitan Peter with collecting funds for the restoration of the Kupyatitsk Monastery near Minsk. Having prayed before an icon of the Mother of God, he heard her voice saying, “Go to the Tsar. He will help build the church.” He then undertook a dangerous trip through Polish-controlled territory to Moscow to collect funds and inform Tsar Michael Fyodorovich about the dire situation of the Church in the occupied southwest.

St. Athanasius of Brest-Litovsk. The year 1596—the year of the institution of the Brest Union— was, in addition to the year of the birth of Metropolitan Peter Mogila, the year of the birth of one of the Orthodox Church’s great heroes in the struggle against the Unia, St. Athanasius of Brest-Litovsk (†1648, commemorated September 5). The son of an Orthodox Lithuanian nobleman, he acquired an outstanding education from schools run by the Orthodox brotherhoods, and at the age of thirty-two became a monk at the Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius. After living in other monasteries and being ordained to the priesthood, St. Athanasius was tasked by Metropolitan Peter with collecting funds for the restoration of the Kupyatitsk Monastery near Minsk. Having prayed before an icon of the Mother of God, he heard her voice saying, “Go to the Tsar. He will help build the church.” He then undertook a dangerous trip through Polish-controlled territory to Moscow to collect funds and inform Tsar Michael Fyodorovich about the dire situation of the Church in the occupied southwest.

Two years later he was appointed superior of the Monastery of St. Symeon the Stylite in Brest-Litovsk, where he embarked upon an impassioned defense of Orthodoxy against the Unia through his writings and sermons, successfully keeping Orthodox believers in the fold and bringing back many who had strayed. St. Athanasius addressed the Polish king, Vladislav IV, asking him to put a stop to the brutality being visited upon the Orthodox by Polish soldiers and the Jesuits. Although the king was sympathetic to his requests, the Polish officials were not, and the persecutions continued. So severe were they, that it was not uncommon for Roman Catholics to set fire to Orthodox churches on feasts days, so as to kill as many as possible. St. Athanasius approached the king again, and this time a small measure of relief was granted, but it did not last long, and a new persecution began. The saint was arrested and imprisoned for three years, and then released.32

Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Seventeenth-century portrait. After the death of Metropolitan Peter Mogila, significant changes began in the Kiev Metropolitanate. The Orthodox began more and more to turn to Russia for protection. Finally, in 1648, the persecutions became worse than ever. A rebellion against Polish and Lithuanian rule broke out in Little Russia. The Cossacks, under the leadership of Bogdan Khmelnitsky,33 began a fierce struggle for independence from Poland, and after their first uprising more freedoms were granted to the Orthodox. 34 However, after a failed second uprising, these freedoms were again lost.

Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Seventeenth-century portrait. After the death of Metropolitan Peter Mogila, significant changes began in the Kiev Metropolitanate. The Orthodox began more and more to turn to Russia for protection. Finally, in 1648, the persecutions became worse than ever. A rebellion against Polish and Lithuanian rule broke out in Little Russia. The Cossacks, under the leadership of Bogdan Khmelnitsky,33 began a fierce struggle for independence from Poland, and after their first uprising more freedoms were granted to the Orthodox. 34 However, after a failed second uprising, these freedoms were again lost.

St. Athanasius was again arrested and imprisoned, along with prominent Orthodox dignitaries. Crying out “Anathema to the Unia!” he was tortured with red-hot coals, flayed, burned alive, and finally shot and beheaded. His body was thrown into a pit, where it was later found to be incorrupt.35

Bogdan Khmelmitsky, with the blessing of the Kiev Metropolitan, appealed to the Russian Tsar in 1654, and became a Russian subject. Moscow then went to war with Poland, which after its defeat in 1655 was forced to cede all of Malorussia (Little Russia) and Belorussia (White Russia) to Russia. Throughout these territories the Orthodox rose up against the Latin Catholics and Uniates.

From The Orthodox Word No. 300-301. Used with permission. Follow the link to find the digital version.