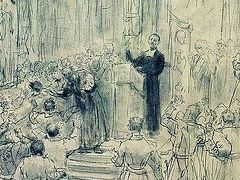

The Baptism of Rus’. Fresco from the St. Vladimir Cathedral in Kiev, Ukraine. Victor Vasnetsov, 1896.

The Baptism of Rus’. Fresco from the St. Vladimir Cathedral in Kiev, Ukraine. Victor Vasnetsov, 1896. The old maxim that “history is written by the victors” always puts us on our guard when trying to make sense of the past in order to make sense of the present. But this maxim only serves to further smudge the edges of real history, because history is not how modern people see the past, but how the people of a given time period saw themselves and those around them. This is especially important to remember in the current age of lightning-fast information exchange, with its unprecedented potential for an ongoing revision of history. As seekers of truth, Christians have to make every effort to understand history with all its nuances and hard facts, so that we might think twice or thrice before joining whatever ill-conceived crusade may be afoot at a given time.

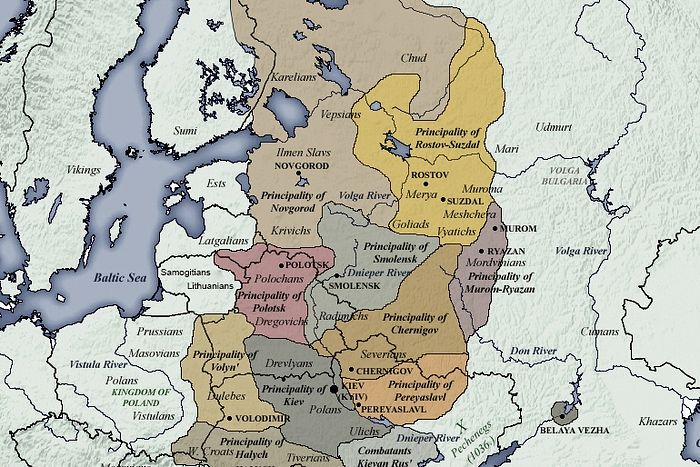

Looming large right now in the information space is a Slavic country now called Ukraine, also called “the Ukraine,” known as “Malorussia” or “Little Russia” when it was part of the Russian Empire, and long before that called, simply, Rus’. If you follow the news, it appears that the political history of this country has become the subject of wild revisionism, and indeed its mind-boggling complexity lends itself to that. In outlining the history of Christianity in the Ukraine we cannot entirely avoid politics, because we are forced to acknowledge that Christianity everywhere took root and developed under varying and changing political conditions, and Ukraine is no exception

But temporarily setting aside modern complexities, we’ll begin by looking back to distant, apostolic times, when the light of Christianity was just beginning to penetrate the tenebrous dominions of Scythes and Slavs.

1. Apostle Andrew

Apostle Andrew setting up a cross of the hills of Kiev. Miniature from a fifteenth-century Russian chronicle.

Apostle Andrew setting up a cross of the hills of Kiev. Miniature from a fifteenth-century Russian chronicle. Early Russian history was researched and recorded by the most literate people of those days—usually monks. The father of Russian history is considered to be St. Nestor the Chronicler († ca. 1114, commemorated October 27), a monk of the Kiev Caves monastery, whose relics remain there to this day. If it seems strange to the modern ear that we call a monk of the Kiev Caves monastery the father of Russian history, we can only reply that this simple fact, confirmed by centuries of written history, underscores another fact: that in those days, when Christianity had finally taken root in the Kievan lands, there was no Ukraine—only Rus’

Many Russian chronicles talk of the Apostle Andrew’s preaching to the people of Rus’—most notably the fourteenth-century Lavrenty Chronicle, which used Byzantine chronicles as source material. Additionally, in the early third century, St. Hippolytus of Portuense writes in his work on the twelve apostles: “After preaching to the Scythes and Thracians, Andrew endured death on the cross in Patras….”1 Origen also makes similar reference to St. Andrew preaching to the Scythes.2 Ancient Scythia encompasseв many lands and peoples, but from Hippolytus’ words, “the Scythes and the Thracians” it can be concluded that the Apostle Andrew preached to those Scythes adjoining Thrace—those who inhabited the Balkans and the lands beyond the Dunai [Danube], including what is now Southern Russian and Ukraine.3 Modern historians have even traced the Apostle Andrew’s fourth journey from Jerusalem around the Black Sea to Kiev, and thence to Moscow and even Karelia.4 Well known is the tradition of St. Andrew’s prophecy on the hills of Kiev: “Do you see these hills? Upon these hills shall shine forth the beneficence of God, and there will be a great city here, and God shall raise up many churches.” According to his Life, the apostle went up around the hills, blessed them and set up a cross. Having prayed, he went up even further along the Dniepr River and reached Novgorod.5

This same Dniepr River was the connecting line between the group of eastern Slavic tribes that would unite to become Rus’, with Kiev as their capital. One could travel from Novgorod along its waterways, then portage to the Dnieper and reach Kiev. Continuing south to the Black Sea, one would stop in the Crimea, and carry on to Constantinople. This was a well-travelled trade route, which would in time connect Russian Christians with Greek Christians. The southern coast of Crimea being part of the Byzantine Empire, with Greek Christian settlements, it was naturally the first part of the future Russian Empire where Christianity took root. The missionary work begun by St. Andrew was continued by St. Clement of Rome (†101, commemorated November 25), who arrived in Taurida (Crimea) with a large number of his Roman flock. After St. Clement worked a miracle, pagans from all over the peninsula were drawn to him and hundreds received baptism every day, so that after only one year, paganism was uprooted from southern Crimea, and seventy-five churches were established.6

Archeological evidence shows that there were some churches established along the Viking trade route in the time of the Apostle Andrew, but the Slavs of the regions around Kiev and Novgorod were so utterly pagan that any new converts to Christianity were severely persecuted. However, there is proof that Christians were living in Kiev before the Baptism of Rus’ in 988. One indicator is the Byzantine record of a diocese of “Rossia” centered in Kiev, from 862/863. It is supposed that St. Cyril (brother of St. Methodius) baptized some of the Rus’ during his missionary travels to Khazaria in 860. There is also a written record of two Christians killed by pagans in Kiev in 983. Theodore refused to yield his son John as a human sacrifice to the god Perun, and now father and son are considered the first martyrs of the Russian Orthodox Church (commemorated June 12).

There is also record of the baptism of the Scandinavian prince Askold. Askold was one of the earliest rulers of Kiev; he was travelling along the Dniepr trade route when he discovered the beautiful, hilly town, and conquered it to be his own. Other Varangians—the Byzantine term for those warriors from the north—came to live in Kiev, and later attacked Constantinople in Askold’s army. The Byzantine capital was miraculously saved from this attack; the Orthodox Patriarch sent missionaries to Kiev, who baptized Askold. Modern historical sources express doubts about the baptism of Askold, but the Russian chronicles do not. It is also supposed that Askold was murdered by pagan warriors precisely because he had become a Christian.

With the murder of Askold began the reign of Rurik, a Scandinavian originally invited by Novgorodians to unite the squabbling Slavic tribes. The Rurik Dynasty would produce Grand Prince Vladimir of Kiev, canonized as the Baptizer of Russia (†1015, commemorated July 15).

Here again we have the phrase “of Russia,” when we are talking about events in Kiev. That is because at the time of Kiev’s Christianization all of the Slavic peoples inhabiting the regions of what are now Russia and Ukraine were called the Rus’, mainly by the Roman Empire (with Contantinople as its capital). There were different tribes always at war with each other, but the Slavic-Varangian people who made themselves known to the Roman Empire were called Rus’. When St. Vladimir united them all under the new religion, these warring tribes became a new people, all united and made one ethnos by Orthodox Christianity.

2. The Baptism of Rus’, in Kiev

Grand Prince Vladimir was the grandson of Princess Olga, who was married to Igor, the son of Rurik. Although St. Olga herself became a Christian, she was unable to bring her children to the Christian Faith. But when Olga received baptism in Constantinople in either in 955 or 957, she also had her maidservant, Malusha, baptized with her. Malusha was the daughter of the Drevlian7 prince who had killed Olga’s husband, Igor. Malusha would become her daughter-in-law, and give birth to Prince Vladimir.

Vladimir, half Viking, half Slav, had a natural talent for ruling, and a strong appeal to the Russian people. He became the prince of Novgorod and later conquered Kiev, uniting the three existing princedoms of Novgorod, Kiev, and the Drevlian capital—in some cases peacefully, in others, by the sword. He was thoroughly pagan and a hedonist, but he had an inherent urge to unite—first the cities, and then the religious cults. In Kiev, he erected all the idols known to the Kievans, but he was becoming more and more aware of the advantages of monotheistic religion. It is said that Vladimir saw in the Christian religion a means of uniting all his subjects, and the influence of his righteous grandmother and an inner longing to find the one true religion led him, after an investigation of the major monotheistic religions, to Orthodox Christianity.

When the Byzantine co-regent brothers, Basil the Bulgar-Slayer and Constantine, turned to Vladimir for military assistance against the mutinous regiments of Bardas Skliros and Bardas Phocas, Vladimir consented, providing they give him their sister, Princess Anna, in marriage. The Byzantine rulers were loath to give their sister to one they considered a barbarian, but when with Vladimir’s help they successfully defeated the rebellion, they were finally forced to comply, although not without military threats from Vladimir. Part of the agreement, however, was that Vladimir be baptized Christian.

St. Vladimir, Equal-to-the-Apostles (center) with his sons, Passion-bearers Boris and Gleb. Icon from late fifteenth-century Novgorod.

St. Vladimir, Equal-to-the-Apostles (center) with his sons, Passion-bearers Boris and Gleb. Icon from late fifteenth-century Novgorod. Tradition has it that just before his baptism at Chersonese on the Crimean peninsula, Vladimir went blind. Abandoned by all but the Greek priests sent to catechize him, he descended into the baptismal font, and emerged a new man. Gone were both his physical and spiritual blindness. St. Vladimir changed the course of Russian history, bringing all of Kiev to the Dnieper for Baptism with the words, “If anyone does not go into the river tomorrow, be they rich or poor, beggar or slave, that one shall be my enemy.” That everyone appeared willingly at the river shows how great Vladimir’s authority and popularity already were, and how the people respected the source of his newly acquired glory as “Tsar.” But as we recall, the seeds of Christianity had already been planted in the land of Rus’, particularly in the southern lands, and here was the crown of the endurance of these Christians.

Vladimir went on to convert Novgorod and other parts of the realm, including various pagan tribes of the steppe. His rule was just, generous, wise, and strong, and his subjects adored him. The new glory of his budding Christian realm attracted other nationalities to his religion. His Life mentions: “In the Nikol’sk Chronicles under the year 990 was written: ‘And in that same year there came to Volodimir (Vladimir) at Kiev four princes from the Bulgars [Moslems] and they were illumined with Divine Baptism.’ In the following year ‘the Pecheneg prince Kuchug came and accepted the Greek faith, and he was baptized in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and served Vladimir with a pure heart.’ Under the influence of the holy prince several apparent foreigners were also baptized; for example, the Norwegian ‘koenig’ (king) Olaf Trueggvason (†1000) who lived several years at Kiev, and also the renowned Torvald the Wanderer, founder of a monastery of St. John the Forerunner along the Dneipr near Polotsk, among others. In faraway Iceland the poet-skalds called God the ‘Protector of the Greeks and Russians’.”8

Orthodox Christianity blossomed mightily under Vladimir, and everywhere idols fell and churches and monasteries were built. The hierarch of Kiev was titled Metropolitan, and the succession of Kiev Metropolitans established other dioceses: at Novgorod, Vladimir-Volhyn (opened May 11, 992), Chernigov, Pereslavl, Belgorod, and Rostov. These were the major cities of Rus’; there was no Moscow yet. Christianity was, however, most fully and readily embraced near Kiev, which is why Kiev is still called the “Mother of Russian cities.”

Metropolitan Makary (Bulgakov) of Moscow and Kolomna9 in his work on the history of the Russian Church emphasizes the development of the Russian nation as taking place parallel to and intertwined with the introduction and flourishing of Christianity under St. Vladimir and afterwards. “And if we remember (as an historian must always remember), that here also, as in all other events and processes of the world, regardless of all apparent differences, there was one invisible, supreme Actor—God, Who moves and directs all toward one high goal, although through varying ways, then we must come to the question: What does this precise concurrence of two highly important events in one and the same people mean? … Did not He [the Lord] thus unite them [Church and state] even from the first minutes in indivisible bonds, as the body and soul are united in man? … to live one, common life, yet completely retaining their distinguishing qualities?... Thus, was this not mutual, beneficial, and natural cooperation with each other preordained by the Most High for the Russian people and the Russian Church, as He united them from the very beginning?”10

3. Early Clash with Roman Catholicism

Vladimir’s reign placed the foundation of Orthodox Russia, and he made this foundation strong through his unifying efforts. Under him an Orthodox nation grew from disparate princedoms, although not without great struggle. Even during Vladimir’s life, a threat to Orthodoxy was looming in the West, in the realm of another Slavic nation— Poland. This nation would play a large, antagonistic part in the future of Orthodoxy in what would later come to be known as the Ukraine.

If we pause at this time in history to take a bird’s eye view of the Christian world, East and West, we can see that a rift is forming. The Byzantine Empire is shrinking; the Pope of Rome, under Frankish influence, has inserted the filioque11 into the Creed, nursing also ambitions of eclipsing all the other Orthodox Patriarchs as “Christ’s vicar on Earth.” In fact, he is convinced of his supremacy, but the other Patriarchs do not agree. Jurisdictional territories in the Balkans, Southern Italy, and Sicily are under dispute. And now a new nation of formerly wild barbarians in the northeastern expanses is growing, and they are solidly attached to the Constantinople Patriarchate. This rift was bound to spread upwards and divide the Slavs of the West from the Slavs of the East, and the division would prove to be a violent stormfront and a painful wound.

While Rus’ received Christianity from the Greeks in 988, Poland’s Christianization dates to just slightly earlier, in 966, with the baptism of Mieszko I, the first ruler of the Polish state, along with much of his court. But Poland did not experience the swift, sweeping conversion that St. Vladimir effected in Rus’. It took the predominantly pagan Poland several centuries to become a Christian country, despite the efforts of Mieszko I. The first Christian influence came from the East; Mieszko’s wife was Bohemian, and her country’s religion dated back to the work of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, enlighteners of the Slavs. But Poland’s proximity to Germany made it an object of heavy-handed Teutonic missionary work, and the ecclesiastical alignment shifted west. In order to avoid German domination, the Church in Poland gradually submitted itself directly to the Vatican. The Polish King Boleslav the Brave was especially loyal to Rome, and strove through military conquest to make the Latin Church dominate over the Slavs of both East and West, under the aegis of Catholic Poland.

Vladimir had a rivalry with Poland even in his pagan years, and conquered several Lakh (an east Slavic name for Poles) cities in an area that came to be known as Galicia, or Chervonaya Rus’—Red Russia, also called Ruthenia. (Note that just like Rus’, Poland was not a united country before Christianization. Its territory expanded and contracted, and tribes warred amongst themselves.) Later, Boleslav became Vladimir’s main enemy, and in 1013 Vladimir was forced to foil a conspiracy in Kiev inspired by Boleslav’s cleric, the Kolobzheg Catholic bishop Reibern. Vladimir’s son Svyatopolk (by a pre-Christian wife) was married to Boleslav’s daughter and became the first instrument of betrayal against Orthodoxy, through his own lust for power

After Vladimir’s death, Svyatopolk had Vladimir’s sons by Princess Anna, Boris and Gleb, murdered, so that he could seize power (for this crime he went down in history as “Svyatopolk the Accursed”). But this Russian Cain did not ultimately succeed. He looked to the Poles for help with no regard for their militant Catholic intentions. Boris and Gleb, who knew of the conspiracy but refused to lift their hands

against their brother, are now saints of the Church—holy passion-bearers († ca. 1015, commemorated July 24). By their prayers, the Russian Orthodox Church lived on. Threatened by a militarized Roman Catholic Church almost from the beginning of its existence, it was saved in a mystical way through the meekness and endurance of its early sons.

Power struggles continued in Kiev, and became almost inevitable, prince after prince. But the Orthodox Faith grew despite these tumultuous external circumstances. The Church hierarchy, mostly Greeks, earned the respect of their flock. The Rurik dynasty continued, each ruler having his own human foibles and downfalls, but the Orthodox Faith was held sacred, and the princes understood themselves to be its guardians. So quickly and deeply did Orthodoxy take root among the Rus’ that monasticism—the litmus test of Christianity—developed early among the native peoples of the land, producing numerous saints.

4. More Problems from the Latins

Attempts by the Roman Catholic Church to gain the newly enlightened Slavic lands for itself continued in Kiev. The Russian people seemed to be inoculated against it by the strong, beneficial influence of their hierarchs and monks, but the weak link was always in the elite classes, who were lured by the growing might of the Latin world, and pressured by their Catholic peers.

In the 1070s there was a power struggle among the sons of Grand Prince Yaroslav of Kiev. Izyaslav Yaroslavich turned to Pope Gregory VII for help after being exiled from Kiev by his brothers, and the pope tried to use this opportunity to his own ends. He and his religion then proved to be unnecessary when Izyaslav succeeded without them. In the 1080s Pope Clement III of Rome sent an offer to Metropolitan John II of Kiev to join the Latin Church, but the latter only returned the offer with a letter rebuking the errors of Rome. In 1207, Pope Innocent III sent an epistle to all Russian princes, clergy, and people saying that although they had long been distanced from “their mother’s breast” (that is, the Roman Church) the pope simply could not repress his fatherly feelings and was calling the Russians to himself. The entire Greek Church, he said, had now accepted the authority of the Apostolic See, and how could it be that a part of it (the Russian Church) did not follow?

The pope’s persuasion would have been humorous if it were not so sad and cynical—Constantinople had been sacked during the fourth crusade (1202–1204), its churches desecrated, and its hierarchs and clergy forced to submit to Rome. By referring to Constantinople’s “submission,” the pope’s words sounded more like a threat veiled in an invitation to return to the mother’s breast and father’s embrace. A similar epistle was again sent to the Russian princes by Pope Honorius III in 1227, and Dominican friars were sent to Kiev to discuss it three years later, but they were dismissed unceremoniously by Grand Prince Vladimir Rurikovich. The Eastern Slavs, beside being forewarned by their Greek enlighteners, combined good sense with stubbornness, and none of these attempts succeeded. No less important was the Slavs’ ability to fight

Less fortunate were the Orthodox of the western lands of Rus’, where Latin propaganda was introduced with the aid of Danish, Hungarian and Livonian swords.

The lands bordering western Rus’ were under siege by the Brotherhood of the Sword, the Teutonic Knights. This was an expansion of the Holy Roman Empire, by means of the Germans. In Livonia—what is now Estonia, Latvia, and some territories bordering—even former pagans that had been baptized were so horrified by the violence of these Germanic “brothers” that they threw themselves into the Dvina River to “unbaptize” themselves. But strong fortresses and swords finally prevailed, and the Order of Livonian Knights was formed. The Russian presence in these lands waned

The far western part of southern Russia (reminder: southern Russia would only much later be called the Ukraine)—Galicia—also came under Latin pressure. It had been conquered in the late eleventh century by the Hungarians, who began a fierce persecution of the Orthodox. The Galicians were saved in the late twelfth century by the Russian prince Roman Mstislavich of Volhynia, who annexed Galicia to his Volhynian princedom. At that time, the Roman pope was reaching the height of his power: Constantinople was his captive, and none other than he was bestowing crowns upon European kings. He could not bear to see a strong prince not crowned by him, and made the usual sugarcoated offer to Prince Roman in a way that could be interpreted as: “All these dominions will I give to you if you will bow down to me.” “Does the pope have a sword like mine?” Prince Roman answered as he struck a blow with it for emphasis. However, after Roman’s death, Galicia again fell to the Hungarians. Again came the Latin priests and monks, who exiled the Orthodox clergy, turned the Orthodox churches into Catholic ones, and began to force the population into the Roman Catholic fold. In 1220, the Russian prince Mstislav Udaloi again wrested Galicia from the Hungarians, but this conquest brought no benefit to the Orthodox, since he used his prize as a dowry for his daughter, whom he gave to the Hungarian prince in marriage. After his death in 1228, the Latin Church again began a persecution against the Orthodox, which ended when Prince Roman’s son Daniel took the throne of Kiev in 1239.

5. The First Russians to Become Metropolitans of Kiev

Up to 1051, all the Metropolitans of Kiev had been Greeks, chosen by the Patriarch of Constantinople. When the last one died and a new one was not sent for three years (perhaps due to a war between Prince Yaroslav the Wise and the Greeks), the prince decided in 1051 to chose one himself. His choice, Hilarion, asked the blessing of the Patriarch of Constantinople that same year, and it was granted. Both Hilarion, and later Russian Metropolitan Ephraim, were holy ascetics and men of prayer. Ephraim was also known as a wonderworker, and was later numbered among the saints.

The Metropolitans continued to be consecrated in Constantinople. Then the will of Russian princes began to have more power over the choice of Metropolitans. The Greek hierarchs sent to the Russian lands would often flee to Greece when relationships between Russian princes became too heated. When Metropolitan Michael of Kiev returned to Constantinople during an internecine conflict, Prince Izyaslav chose another Metropolitan from among his own people. Clement, his choice, was of unimpeachable character. Disputes ensued as to whether or not he could be consecrated by a synod of bishops, rather than by the Patriarch. It was suggested that the Constantinople blessing be substituted by Rome’s. This cast a shadow over Clement, who was appointed, but not accepted by those who adhered to the Greek side. Allegiance finally returned to Constantinople, but now the Russian prince’s opinion would be taken more into consideration.

Without looking very closely, it is difficult even to see where, in Church matters, Constantinople ended and Rus’ began. Unlike Rome, Constantinople did not use the Church to enslave and subdue newly Christian peoples, and the fact that most Kievan hierarchs were Greek did not cause the princes of Rus’ to suspect any political maneuvers. In fact, because the Russian princes were so often vying with each other in internecine wars, a politically aloof Greek Metropolitan was a stabilizing factor in society. But the time was coming for Church leaders to come forth from among the Russian people—men who could win over die-hard pagans in outlying areas. Another reminder: “outlying areas” at that time were Rostov, Moscow, Suzdal, Ryazan, and places further north—areas we now call Central Russia. Rus’ was, for a very long time, Novgorod, Kiev, and Galicia-Volhynia

We will not go into great detail about the successive Russian princes, and will only say that Russian rule took its ideal from the Byzantine Empire, but it took centuries to grow out of the childhood of sibling rivalry. Despite the piety some princes showed in their own princedoms, they were far from merciful to the Christian princes and subjects of others. A greater influence for good came from the monastics. Much was needed to uproot the strong pagan customs and habits among the masses. But it has to be noted that this work was primarily wrought through education, and the examples of holy men and women.

6. Monasticism

Monasteries, built by St. Vladimir and his successors, appeared in Kievan and Novgorodian Rus’ almost from the beginning of their Christianization. But, as St. Nestor the Chronicler wrote, these were “not like the monasteries built by tears, fasting, and vigils.” That kind of monastery was the Kiev Caves Lavra, founded by Sts. Anthony and Theodosius—considered the fathers of Russian monasticism

The Sevsk Icon of the Theotokos, also depicting Sts. Anthony (right) and Theodosius. Painted in the 11th century by St. Alypius the Iconographer

The Sevsk Icon of the Theotokos, also depicting Sts. Anthony (right) and Theodosius. Painted in the 11th century by St. Alypius the Iconographer The Kiev Caves monastery gradually became the light to all other Russian monasteries, and a great influence for good to the entire population. New monasteries opened with the inspiration to be like it, and lay people were drawn to these monasteries like bees to honey. Although the monasteries were eventually bestowed with lands and serfs, in most cases these properties were used to benefit the local population, and thus the moral authority of Russian Orthodox monks only grew

7. The Mongol Invasions and the Fall of Kiev

It can be said that Kiev was first taken from the rest of Rus’ by the invasion of the Mongol Tatars, known as the Golden Horde, between 1237 and 1240. This invasion did not spare other Russian principalities, but Kiev was utterly razed, as was Peryaslavl, Chernigov, and cities in Volhynia and Galicia. The Desyatina Church and the St. Sophia Cathedral, both built by St. Vladimir, were destroyed. The Kiev Caves monastery was razed, and the monks fled. The Mother of All Russian Cites was reduced to two hundred homes.

The significance of this historical event cannot be underestimated in Russian-Ukrainian history. The southern lands of Rus’ were turned into deserts by this unanticipated whirlwind from the Far East, while the northern areas, especially along the River Volga, became the population’s refuge. Northern Rus’ was also subject to incursions, but its princes managed to find a way to live under the Mongol Yoke without having to capitulate entirely. Great Kiev, however, was gone, and the center of Church life began its migration to Vladimir, near Suzdal, and later to Moscow.

In Galicia, the Mongol Yoke meant trouble for the struggle between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. Northern Russia had the wise and valorous St. Alexander Nevsky (†1263, commemorated November 23) to foil the plans of Pope Innocent IV, who used the Swedes to attack the Russians with the ambition of spreading Latinism to the Finnish tribes. Galicia-Volhynia, however, had the weary Prince Daniel Romanovich. Western Rus’ had an experience similar to the Byzantine Empire’s when it had turned to Rome for help against the Moslems. Daniel sent a message to the pope promising to unite with the Roman Church in exchange for an army against the Mongols. The pope sent one charter after another to Galich, allowing the Russians to keep the Greek Rite, promising to send preachers and bishops, granting Daniel the right to confiscate the properties of all princes who refused to join the Latin Church, and bestowing a crown on Daniel. The only promise Innocent did not keep was to send a crusade against the Mongols. No one in Europe was interested. Daniel cut off ties with Rome, and Orthodoxy remained the ruling Faith—until 1340, when the Poles took over Galicia, and the Lithuanians took over Volhynia. The promise of “all these dominions” had again shown itself to be a cruel joke.

Incidentally, Galicia-Volhynia, Kiev, and other regions now called the Ukraine were ultimately saved from the Mongol-Tatars through the exploits and sacrifices of such Russian leaders as St. Dimitry Donskoy in the battle of Kulikovo (1380), and through other decisive battles undertaken by the Russians of the north—particularly those of Muscovy. Help from the Latins did not figure into these victories in the least—on the contrary, Roman Catholic countries such as Poland saw the Mongol Yoke as a good opportunity to spread Catholic influence into Russia.

8. The Inquisition

Lithuania was, at this time, somewhere between paganism and Orthodoxy, and viewed the violence of the Prussian and Livonian Orders with contempt. But, in Galicia, the Polish Catholics began seizing churches from the Orthodox, and establishing bishoprics. Then, in 1381, with the blessing of the Roman pope, Dominican friars arrived to conduct an inquisition.

The superficial nature of the Lithuanian princes’ acceptance of Christianity made them easily turn to the Catholics when it was politically advantageous. The Lithuanian prince Yagelle married a Polish princess and in 1386 received Catholicism in Poland, then demanded that it be introduced in Lithuania. The Poles first began forcing the pagans to be baptized Catholic, and then directed their fervor against the Orthodox, beginning with the ruling class. All who refused were executed. This spread to the surrounding Russian areas, all the way to Kiev, which after its destruction had been taken over by Poland-Lithuania. For the most part, the Lithuanians remained tolerant of Orthodoxy, but the official religion of Vilnius and Kiev was now Catholicism, and a Catholic episcopate was established in these cities. In 1413 the Polish Sjem (Council) decreed that only those Russians who converted to Catholicism would retain their titles. Many did convert, purely for material gain, but when the Orthodox Prince Svidrigailo succeeded the Lithuanian Prince Vitovt, there was brief triumph of Orthodoxy in the land (1430–1432), which ended when Sigismund was sent from Poland to ascend the throne. Orthodoxy was again overthrown by force, and its churches destroyed. Finally, the Union of Florence12 gave the Catholic Church a new plan for ending what promised to be an endless, violent seesaw from Eastern to Western Christianity and back again.

Meanwhile, the Orthodox Church in Rus’ was nearly in a shambles due to the Mongol Yoke. The Patriarch of Constantinople sent Cyril II as Metropolitan to Kiev, when the former Metropolitan disappeared during the city’s sacking. He arrived at the ruins, and was forced to move his cathedra to another city, which became Vladimir in the north. Thus did Kiev lose its place as first among Russian cities physically—but not spiritually. For centuries after, until the establishment of the Russian Patriarchate under the Moscow princes, the first hierarch of the Russian Church was always titled, “Metropolitan of Kiev and all the Russias,” even when he was physically situated elsewhere.

9. The Division of the Russian Church into the Moscow and Kiev Metropolitanates

By the mid-fifteenth century, Orthodoxy had become the main religion in Muscovy, protected by a strong government, and able to resist all influence from Rome

This was not the case in the western regions, where the Orthodox were the persecuted subjects of a Catholic government. Now, the center of Russian Orthodox gravity was Moscow, and those who, at great cost, retained their Orthodoxy in Poland and Lithuania, felt the pull. Lithuania had a large Russian Orthodox population, including members of the nobility, but when it united with Poland, these Orthodox people increasingly became an inconvenience to their rulers. Prince Vitovt set up a Lithuanian Metropolitanate in Kiev with the aim of gathering his Orthodox subjects into a fold that could be separated from powerful Moscow. This placed the Orthodox Church within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in a weak, unprotected position.

Moscow had decisively rejected the Union of Florence and imprisoned its harbinger to Russia, Metropolitan Isidore. (This, incidentally, was a strong factor in the establishment of Russian autocephaly.) But Isidore was allowed to escape, and died in 1463 as the Roman Catholic dean of the college of cardinals. His disciple, Gregory, attempted to introduce the Union into Lithuania. He did not succeed, and ten years later himself even joined the Orthodox. As Orthodoxy was still strong in Lithuania, the Lithuanian princes could not confront it directly and coerce it entirely into the ecclesiastical union that they hoped would follow the political union with Poland. Therefore they set about to weaken it, to bleed and starve it.

This was achieved by again withdrawing all titles and lands from those nobles who would not convert to Catholicism, so that Orthodoxy would more and more be looked upon as the religion of the lower classes. The Polish and Lithuanian kings were also conferred the privilege of “patronage” over monastery and church property, to appoint bishops and clergy, and even to run the monasteries on the lands given to them through opportunists who were on the king’s payroll. This had the effect of undermining the authority of the Orthodox Church by depriving it of worthy leaders.

The faithful of the Kiev Metropolitanate realized the danger to their existence and tried to alleviate it by growing closer to the Patriarch of Constantinople. But this closeness could not change the fact that Kiev Metropolitans had to be approved by a Catholic king and, just as in Moscow, the Metropolitan of Kiev was chosen by a synod of bishops. As for the actual city of Kiev, none of the Metropolitans even visited it. The only one who tried was Macarius I in 1497, but he was killed by the Tatars in the city of Mozyr.

So, one can see what a difficult time this was for the people who would much later be called Ukrainians.

From The Orthodox Word No. 300-301. Used with permission. Follow the link to find the digital version.